* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Orchestral Texture and Unison Composition

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

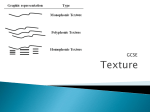

Orchestral Texture and Unison Composition by Artemus Introduction When composing for orchestra, the most important concept is that of balance which comes from knowledge of instrumentation; not just in terms of their tone but their characteristics in different registers and subsequent dynamics, as well as how they work in combination with other instruments. This is what separates the amateur beginners from the experienced pros. Good orchestration will demonstrate little to no redundancy in its use of the instruments and the combinations of the instruments used and the respective sounds that they produce will support each other to bring out the melody and the texture of the music. A novice orchestrator will find it tempting to employ too much of the vast array of sounds available from the orchestra at one time or lack taste or discretion when developing the musical ideas throughout a piece. Redundancy is best avoided by understanding the orchestra as an organic ensemble and appreciating the role and capabilities of every instrument. Of course this takes a lot of time and experience can only be gained through critical listening of many scores and by writing with emphasis on the balance – using the resources available as intelligently as possible. When studying scores, a first effective approach when learning to appreciate instrumentation is by focusing on one particular instrument at a time and identifying how and when it is used, as well as the tones and dynamics it creates. Compositional Texture Music is generally composed of a melody and harmony, but the key ingredients of a composition can be in grouped into some or all of the following elements: • Foreground: the most prominent voice heard; usually the melody • Middleground: supporting countermelodies or contrapuntal voices • Background: accompaniment/harmony including bass voices • Rhythmic: percussive elements Not all of these elements are used at one time and at times, it can be ambiguous as to which is which. Homophonic textures are essentially foreground-background, whereas in some contrapuntal music, such as Baroque fugues, it can be unclear what is the foreground and what is the middleground. When composing, making decisions as to how these elements are formed and keeping them balanced will help structure the music and maintain the overall balance. When designating instruments to each of these elements it is best to keep the background in registers that are less poignant and use the most characteristic or expressive register of the instrument that plays the melody. The foreground can also be brought out by contrasting the technique used for the foreground and background instruments, e.g. the melody can played by the violins whilst the accompanying harmony is played by pizzicato or con legno violas and cellos. Contrast is also easily achieved by using the different sections of the orchestra. Melodic lines can also be strengthened through doubling or coupling with other instruments. These elements can be studied in all music and examples of different ways in which they can be presented are too numerous to even list. However, there are some ways in which ideas are commonly presented. One such method is the use of unison and octaves to clarify a melodic line or strengthen its impact. Although, before I begin a discussion on this, it is best to appreciate the meaning of “tutti” - a direction that indicates the use of all instruments. However, it is not always to be interpretted as all of the instruments, it can be a partial tutti which directs the use of most of the instruments that are pertinent to the passage being played. Do not fret though, it's meaning is usually quite obvious when encountered in scores. Unison and Octave Tutti Writing parts in unison or coupling at the octave is an effective method of projecting the melodic line and is often used to present or reiterate a statement or to build up the dynamic of the melody. It entails the use of two or more instruments playing the same passage in parallel. Unison tutti is limited due to the ranges of different instrument but are possible since many instruments have overlapping registers. The sound of the melody is brought further forward and can aid clarity, but it should be noted that when unison tutti is employed, the tonal character is changed and some of the uniqueness of an instruments register can be lost when unison tutti is used with its auxiliary instrument playing in the equivalent range. That said, the homogeneity and size of the string section means that the violins and violas or cellos can commonly play in unison to enhance resonance, and obviously the first and second violins played in unison offer no reduction in tonal character. The entire string section can only play in unison in the alto-tenor region but the effect can give an intricate texture and be quite powerful when played forte and rich in quiet passages. An example is shown below. Example 1 In example 1, a number of instruments are shown to be playing in unison. I have not provided dynamic markings but the audio sample provided should give you a good indication as to the effect I envisioned. This example demonstrates the melody carried by the string section played in unison, except for the double bass (contrabass) which plays at the octave. A counter/supporting melody is played by the bassoon which is reinforced by the bass clarinet playing in unison. The brass section can be considered to hold the background accompaniment and help structure the rhythmic element. The trombones and tuba play in unison, which supports the chords of the horns and trumpets who play the same parts divisi in octave tutti. Octave tutti enables passages to be played in parallel with less instrumental limitation. Octave tutti, where instruments play the same passage but at different registers, is much more common and opens up the possibilities for multi-timbral textures with wider spacing. Similarly, it serves to project a melodic line or idea but it can be more emphatic and clearer, making a much bolder statement or reinforcement. Cellos and double basses are often found to double at the octave. The use of this method to present a resounding musical statement is often used to good effect before a more contrapuntal section or complex development. The clearest example of this is found in the first movement of Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik where the string section plays tutti in unison and at octaves. The use of octave tutti can also be used to dynamic effect such as creating a crescendo by introducing more instruments. Example 2 shows a passage of the string where this occurs. Example 2 The unison and octave tutti techniques can be extended to other instruments of the orchestra. Since the woodwind section has the greatest diversity in timbre, the effects of octave tutti can present quite remarkable results with lots of scope for colour. Individual instruments can also be enhanced by coupling with other instruments. For example, when coupling the clarinet with the flute playing an octave higher, although the flute is playing in its prominent register and carries further, the clarinet provides a warmth and fuller tone than if the flute was played solo. Example 3 introduces an idea where I demonstrate the use of a quiet tone of the clarinet and then in example 4 the melody is coupled with the flute an octave higher, producing the effect described. This sound can be opened up even further by introducing the bassoon to play in the octave lower, which suits the bassoon as it can be played in its most lyrical register and so the melody easily soars with clarity. This is demonstrated with the same melody in example 5. Instead of the clarinet, I have included the unique sound of the oboe. Not only to add a further dimension to the melody but to avoid redundancy, in turn bringing out the bassoon. The clarinet would tend to be masked if played with the same dynamic as in example 3 and to play at a louder dynamic would alter its character and dispel the delicacy of this passage. Example 3 Example 4 Example 5 Brass combinations often employ unison and octave tutti to dramatic effect. Less bombastic couplings are also used. It is common to hear deep, resonant, and sometimes romantic passages with the melody played by the horns and the cello. Similarly, the trumpet and oboe are coupled to produce very clear tones. The tuba can also couple the double basses as a supporting foundation. In example 6 I have presented an example of some octave tutti that can be used in a typically tense or bold context. The cello and double basses play in parallel in octaves with the addition of the double basses also playing in unison in the second bar in order to increase the dynamic. The first part of the melody phrase is carried by the horns and trumpets which are the more agile instruments of the brass; they play an octave apart and, as can be heard in the audio file, they remain mezzo piano to allow for a dynamic increase towards the last bar. The trombone enters the second half of the phrase to increase the dynamic and add an extra dimension to the melody. The brass here are playing in a three octave spread. The final punctuation in the last bar uses a combination that is often used to given an articulated lower punch which has a dark and not too subtle effect; octave tutti is used with the horn, trombone, tuba, cello, double bass, and bassoon. The accompanying audio file includes percussive elements (a snare drum, timpani and 12'' crash cymbal) that have not been scored in the example. The timpani mainly reinforces the rhythmic pattern and bass line provided by the cello and double bass combination. Also, although it is not specified, the cello is played sul ponticello. The examples presented in this article only demonstrate a very small selection of ways in which unison-octave tutti can be used in combination with instruments of either the same or different family. There are hundreds of ways in which this technique can be used and sometimes it is best to experiment whilst remembering the relevance of different timbres available for all the different instruments. However, playing and writing with this simple but effective technique is the best way to begin appreciating all that was discussed about instrumentation and about combinations. Example 6