* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

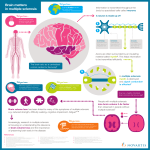

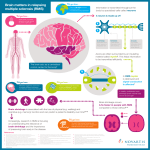

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS: A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW INTRODUCTION Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, debilitating neurodegenerative disease. The basic disease process of multiple sclerosis is characterized by inflammation and then destruction of the myelin sheaths and axons in the central nervous system, e.g., the brain, brain stem, spinal cord, and optic nerve. Patients typically experience phases of remissions and phases of relapses, although there can be variations in the clinical presentation. The exact cause of MS is not known, but MS is most likely caused by an environmental trigger in a susceptible individual. There is no cure for MS. OBJECTIVES When the student has finished this module, he/she will be able to: 1. Identify a basic definition of MS. 2. Identify the basic disease process of MS. 3. Identify the basic pathophysiological process that causes the neurological damage of MS. 4. Identify the correct definition of myelin. 5. Identify the three basic causes of MS. 6. Identify three environmental causes of MS. 7. Identify the three requirements for making a diagnosis of MS. 8. Identify the correct definition of clinically isolated syndrome. 9. Identify the two most common forms of MS. 10. Identify three common signs and symptoms of MS. 11. Identify the pattern of presentation of the most common form of MS. 12. Identify the class of drug that is used to treat MS relapses. 13. Identify three drugs that are used to modify the course of MS. 14. Identify two psychosocial problems commonly associated with MS. 15. Identify two non-pharmacological interventions that can help patients with MS. EPIDEMIOLOGY There are approximately 400,000 people in the United States with MS, and approximately 10,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.1 Multiple sclerosis primarily affects women (3:1 ratio) and Caucasians.2 The disease is also far more common in northern latitudes, and MS is almost unknown near the equator.3 The disease most often develops in people aged 18 to 50 years of age, but it can happen it develop at any time of life.4 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY The pathophysiological process that causes the signs and symptoms of MS is not completely understood. It probably begins when pro-inflammatory T lymphocytes are activated by an antigen. (Note: A T lymphocyte is a type white blood cell that is involved in cell-mediated immunity. There are various types of T lymphocytes, all with a different action they perform once they are activated. The T stands for thymus; T cells mature in the thymus). The activated T lymphocytes cross the blood-brain barrier and secrete proinflammatory cytokines that in turn activate B cells, macrophages, and other T cells.5 These cells initiate and sustain an inflammatory process that damages the myelin sheaths and the axons. The name of the disease – multiple sclerosis – is derived from the multiple sclerotic lesions that result from this process. Learning Break: Myelin is an insulating material that surrounds the axon of a neuron. Myelin increases the speed at which nerve impulses travel along the nerve fiber, and it also prevents the nerve impulse from leaving the nerve fiber. A crude but somewhat accurate way of picturing myelin is to imagine it as the insulation around an electrical wire. Because the wire is surrounded by insulation, the electrical current does not “leak” into the surrounding area and the current moves more quickly and efficiently down the wire. THE CAUSES OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Multiple sclerosis is most likely caused by a complex and poorly understood interplay between environmental “triggers” and genetic factors that confer susceptibility. There is also evidence that MS is in part an autoimmune disease or the disease process is mediated by an autoimmune response: an environmental trigger initiates and sustains an autoimmune response. in someone with a genetic susceptibility to MS. 6,7 Environmental Causes of Multiple Sclerosis Cigarette smoking: People who smoke cigarettes have an increased risk of developing MS when compared to people who have never smoked.8 The risk of developing MS increases as the duration and intensity of the smoking habit increases, and exposure to second-hand smoke may increase an individual’s risk for developing MS.9,10 Smoking may also cause MS to progress. Cigarette smoke contains toxins that can compromise the blood-brain barrier, may cause demyelination, and can cause damage to axons. These toxins may also affect the immune system and predispose the smoker to autoimmune diseases such as MS and rheumatoid arthritis. Also, people who smoke have more respiratory infections and these infections have been linked to an increased risk for the development of MS.11 Vitamin D: Vitamin D is needed for the absorption of calcium. There are dietary sources of vitamin D, but approximately 90% of the vitamin D we require is synthesized by liver, the kidneys, and the two innermost layers of the epidermis. There is a large body of evidence that strongly suggests that a lack of vitamin D is an environmental risk factor for the development of MS.12 The lack of vitamin D may affect the immune system, e.g., by allowing/increasing harmful activities of lymphocytes and cytokines that can cause the inflammatory process that damages myelin. Epidemiological studies have shown that a low serum level of vitamin D, living in northern latitudes, and exposure to the sun appear to influence the risk of developing MS. Providing vitamin D supplements as a preventative measure would seem to make intuitive sense. Clinical trials using this approach have produced promising results, but there are very few of these studies and they have been small and not well designed.13 Epstein-Barr virus: The Epstein-Barr virus is a virus of the herpes family. Epstein-Barr virus causes mononucleosis, certain cancers, and has been strongly implicated as a cause of autoimmune diseases such as MS.14 Epstein-Barr virus causes a life-long infection, continuous virus production, and has a modulating effect on the immune system. Several studies indicated that the risk of developing MS increased as the level of Epstein-Barr antibody titers increased.15,16 Genetic Causes of Multiple Sclerosis Genetics influences the incidence of MS, but the exact nature and scope of the contribution of inheritance to the development of the disease is not known. Caucasians are at a higher risk for developing MS even when living in the same environmental conditions as Africans and Asians.17 Multiple sclerosis clusters in families; the risk of developing MS is 1 in 3 if an identical twin has MS, and 1 in 1000 if no one in the family has MS. Determining the genetic basis of MS has proved to be difficult. The susceptibility to the disease is polygenic, and there are perhaps 100 common genetic variants that are likely to be involved in expression of MS.18 DIAGNOSING MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS There is no definitive test that can be used to diagnose MS. A diagnosis of MS requires a) documentation of two or more episodes (with signs and symptoms lasting > 24 hours) of signs and symptoms that clearly indicate white matter pathology; these episodes, b) must be distinct and separated by a month or more; and in addition, c) the diagnosis requires that an MRI exam reveal two separate areas of damage to the CNS.19 Cerebrospinal fluid examination: The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of someone with MS will often have elevations of IgG and an elevated IgG index. The IgG index reflects the IgG and albumin levels of the CSF in relation to the IgG and albumin levels in the serum.20 The CSF will also have oligoclonal IgG bands. These are bands of immunoglobulins that are seen in CSF that is examined using protein electrophoresis or isoelectric staining. The result is rather like an x-ray; the patient with MS will have a characteristic “picture” that shows bands of the immunoglobulins. Learning Break: The value of CSF examination is of particular value in predicting the development of MS in patients who have clinically isolated syndrome (this will be discussed in a following section). Imaging studies: A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exam will typically show characteristic white matter lesions.21 Learning Break: The MRI exam can show characteristic lesions, but there can also be non-specific findings that may indicate the presence of MS, but may be cause by other pathological processes. In order to make a diagnosis of MS, MRI and examination of the CSF must be used together, CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Multiple sclerosis is a complex disease, and there are four distinct patterns of clinical presentation.22 Relapsing/remitting MS: Relapsing/remitting MS (RRMS) is the most common form of MS; approximately 80% of all patients with MS have RRMS. Patients have periods of remission and periods of relapse. Many (up to 80%) of patients with RRMS will gradually suffer from irreversible neurological damage and develop secondary progressive MS (SPMS).23,24 Primary progressive MS: Primary progressive MS (PPMS) accounts for approximately 15% of all cases of MS. In PPMS, the patient suffers a steady, progressive deterioration that begins at the onset of the disease.25 Secondary progressive MS: As mentioned earlier, the great majority of people with RRMS eventually develop SPMS: the rate of conversion of one to the other is approximately 2.5% per year.26 People with SPMS experience a steady decline in functional ability that is not associated with attacks. The damage suffered is usually greater than that suffered by patients with RRMS. Progressive/relapsing MS: Progressive/relapsing MS (PRMS) appears to be a variant of the disease that is uncommon (it accounts for ~ 5% of all MS patients). People with PRMS have a steady decrease in functional ability between attacks, but unlike SPMS, the attacks are superimposed on the progressive course of the disease.27 Learning Break: Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) is a term for a neurological episode caused by inflammation or demyelination that is consistent with the pathophysiological process of MS. Clinically isolated syndrome can often be a harbringer of MS. Approximately 60% to 80% of patients with CIS and a documented brain lesion will develop MS, and approximately 20% of patient with CIS and no documented brain lesion will develop MS.28 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS The onset of the MS can be sudden and dramatic, or slow and subtle. The clinical presentation is very varied and unpredictable, and it will depend on the severity and location of the lesions. The patients have sensory, motor, visual, brainstem, and psychological signs and symptoms. Sensory loss (37%), optic neuritis (36%), weakness (35%) and paresthesias (24%) are often reported.29 Many patients experience fatigue, bladder dysfunction (incontinence), constipation, pain, and weakness. Depression is very common, and suicide is 7.5-fold more common among people with MS.30 Learning Break: Optic neuritis characterized by pain, decreased visual acuity, and reduced color and contrast acuity. The relapses that occur and these signs and symptoms seen during a relapse are caused by inflammation and myelin damage. In order to be considered a “true” relapse, the signs and symptoms must last more than 24 hours, and they must be separated from a previous relapse by a month. A relapse can be confirmed with a MRI exam that uses gadolinium contrast. PROGNOSIS OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS There is no cure for MS. The relationship between relapses and prognosis and longterm disability is not clear.31 The majority of patients with MS will eventually develop a neurological disability. Fifteen years after the onset of the disease, only 20% of all patients with MS will not have a functional disability, and 25 years after onset ~ 80% will need assistance in walking.32 Patients with MS rarely die as a direct result of the disease; complications such as pneumonia are far more common, as is suicide. TREATMENT OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Multiple sclerosis treatment focuses on treating relapses (acute care), trying to alter the progressive course of the disease (disease-modifying therapy), and providing symptomatic relief Treating Relapses Acute relapses of MS are treated with high-dose, short-term IV corticosteroids. These drugs will decrease the severity and shorten the duration of the signs and symptoms. However, they will not affect the degree of recovery, they do not decrease the rate of occurrence of relapses, and they do not modify the course of the disease.33,34 There is some evidence that oral corticosteroids can be effective.35,36 Methylprednisolone is the drug of choice. The dose is 500-1000 mg. The drug is mixed with 120-200 mL of IV solution, and the mixture is administered over one to two hours, once a day for three to five days.37 After the IV infusions, the physician will often prescribe oral prednisone, 60 mg to 80 mg, one a day, tapering the dose over the course of two weeks. Learning Break: It is important to distinguish between a true relapse and pseudoexacerbation that may be caused by infection, fatigue, or a change in ambient temperature before using corticosteroids. Disease-Modifying Therapy The disease-modifying drugs are used for patients with CIS, RMMS, and SPMS.38 They are not used for patients with PPMS. They work by modifying the immune response. These drugs have been shown to have multiple benefits:39 Lower relapse rates Milder relapses Longer interval between relapses Improved quality of life Decreased lesion development as seen by MRI Decreased development of disabilities Drugs that are commonly used as disease-modifying agents in MS include: Interferon beta-1a: Interferon beta-1a (Avonex®, Rebif®) has been shown to be effective in modifying the course of MS.40,41,42 The drug appears to work by altering the immune process via several mechanisms, e.g., decreasing T-cell activity, increasing the activity of anti-inflammatory mediators, or decreasing the activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines. As a result, patients have fewer relapses and fewer severe relapses, and there is MRI evidence of fewer lesions.43 Interferon beta-1a can also decrease the incidence of progression from CIS to MS.44 Common side effects include flu-like symptoms, depression, hepatic laboratory abnormalities, thyroid function abnormalities, neutropenia, anemia, and pain at the injection site. Interferon beta-1b: Interferon beta-1b (Betaferon®, Betaseron®) decreases the rate of relapses, decrease the number of patients who will suffer from a relapse, decreases the incidence of severe relapses, and decreases the number of brain lesions seen by MRI.45 (Note: Interferon beta-1b differs from interferon beta-1a only in dosing schedule [every other day versus once a week] and in the basic structure of the drug). Learning Break: Interferon is a naturally occurring substance. It is a glycoprotein, and it helps to regulate immune function and is involved in anti-viral activity. Interferon beta-1a and beta-1b are both given as subcutaneous or intramuscular injections. Glatiramer acetate: Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) is a mix of amino acids that are found in myelin basic protein. Glatiramer acetate appears to work by affecting the immune response that causes myelin damage. It may do so by mimicking myelin proteins that act as antigens; components of the immune system that attack and damage normal myelin would attach to glatiramer acetate, instead.46 Several clinical trials have shown that glatiramer actetate reduces the frequency of relapses and decreases brain lesions detected by MRI.47,48 The drug is given subcutaneously, once a day. Chest tightness, palpitations, shortness of breath, palpitations, and flushing are relatively common, but these signs and symptoms do not cause harm and are transient. Natalizumab: Natalizumab (Tysabri®) is a recombinant monoclonal antibody. It appears to work by blocking T-cell activation and by interfering with the migration of leukocytes in to CNS tissue. Natalizumab was removed from the market in 2005 because it was felt that the risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) was too great. It was subsequently reintroduced, but it can only be prescribed, dispensed, and taken if the patient is enrolled in a special program. It can dramatically reduce the incidence of relapses. The drug is indicated for use in patients who have not responded to other drugs, have relapsing MS, and should be used with other immune modulating drugs; it is intended to be used as a monotherapy.49 The drug is given once a month as an IV infusion. Learning Break: PML is a very serious, progressive neuromuscular disease caused by an opportunistic infection of the white matter in various locations in the brain. Mitoxantrone: Mitoxantrone (Novantrone®) is an antineoplastic drug that targets T-cells, B-cells, and macrophages. It is considered to be a second-line drug because significant side effects (e.g., severe bone marrow depression and cardiomyopathy) are possible, and it is used when first-line agents have failed.50 Mitoxantrone is given as an IV infusion, every three months. Cyclophosphamide: Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®, Neosar®) is an alkylating chemotherapy drug. It has strong immunosuppressant activity, and has been used to treat RRMS and SPMS for many years as a second-line agent when patients do not respond to interferon or glatiramer and cannot receive natalizumab.51 It seems to be most useful for treating MS in younger (ages 18 to 40 years) patient with a reltively short duration of the disease. Numerous studies have shown that it is effective in preventing relapses and improving the quality of life.52 Cyclophosphamide is given as an IV infusion; dosing regimens are individualized. Infertility and bladder cancer are possible. Azathioprine: Azathioprine (Imuran®) is an immunosuppressive drug that is commonly used to treat MS. It has been shown to be effective at reducing relapses and preventing new lesions. The side effects (nausea, vomiting, bone marrow suppression, hepatic toxicity) can be easily manages, and the risk of malignancies can be minimized by using doses less than 600 mg.53 Azathioprine is given orally, once or twice a day.54 Methotrexate: Methotrexate (Rheumatrex®) is an immunosuppressive drug that is used to treat leukemia, psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis. It has been used with some limited success to treat SPMS.55 Learning Break: Cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and methotrexate are considered to be off-label treatments for MS. The drugs used as disease-modifying agents have been proven to be very useful. However, there are still important issues about the use of these drugs that have not been answered. There are a limited number of studies that have directly compared drugs are limited. It is not clear when to start patients on these drugs, and the role of combination therapy – or if there is a role for it – is not known. Symptomatic Treatment The following drugs have been used to provide symptomatic relief:56 Weakness: Dalafampridine (Ampyra®) is a potassium channel blocker that can be used for weakness and heat-related symptoms. Ataxia/tremor: Clonazepam, mysoline (Primidone®), propranolol, or ondansetron (Zofran®) can help alleviate ataxia and tremor. Spasticity: There are many medications that have been used to alleviate spasticity, e.g., baclofen (Lioresal®), diazepam, and dantrolene. Pain: Carbamazapine, phenytoin, tricyclic antidepressants, gabapaentin (Neurontin®) and pregabalin (Lyrica®) can be used to treat pain. Bladder dysfunction: Drugs with an anticholinergic effect (e.g., oxybutinin, hyoscyamine) can be useful if the patient with MS is incontinent. LIFESTYLE ISSUES Psychiatric Issues Multiple sclerosis cannot be cured. Relapses and disabilities can be managed, but they are painful, unpredictable, and affect quality of life. People with MS are twice as likely to suffer from a major depressive disorder or anxiety. Substance abuse and suicide are far more likely in this patient population.57 These issues obviously have profound impact on patients (and the families of patients) personally, socially, and professionally. The treatment for relapses, IV corticosteroids, can also cause psychiatric dysfunction. The incidence and etiology of depression have been closely studied, and there is some completed research on treatment. Much less is known about anxiety and substance abuse in the population that as MS. Depression in the population with MS appears to be underdetected and undertreated.58 Antidepressants can be used, and there is evidence that they can be effective, but the amount of literature that supports their use is small.59 There is much more evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in treating depression in patients with MS.60 Learning Break: Approximately 10% of all patients with MS suffer from pseudobulbar affect (PBA). People with PBA have mood swings are noted to laugh or cry to a degree that is out of proportion to the situation or the stimulus. Fatigue Fatigue affects a large percentage of patients with MS. Approximately 75% to 95% of patients with MS report fatigue and large number (50% to 60%) of them feel that fatigue is the most incapacitating aspect of the disease and a major disruption to their social and professional lives.61 fatigue in patients with MS appears to be more common in the afternoon and aggravated by high ambient temperatures. The cause of fatigue is not known, and it doesn’t appear to be associated with to disability levels or the progress of the disease. Amantadine (Symmetrel®) is an antiviral drug used to prevent and treat influenza A. It can be effective in relieving fatigue, but the evidence for its use has only reached Level II.62 Modafanil (Provigil®) is an analeptic that works (probably) by increasing the level of monoamines such as noradrenaline and dopamine. It has been used off-label to treat fatigue in patients with MS, and there is some evidence for, and some against, its effectiveness.63,64 Exercise and Exercise Tolerance At one time it was thought that patients with MS should not exercise. But research during the last ten years has shown that resistance and endurance exercise can improve the physical condition of patients with MS and the improvement of physical condition improves the quality of life.65 Patients are now advised to exercise after consulting with a physician. Two to three days a week is a reasonable schedule. Patients must be counseled that exacerbations of the signs and symptoms of MS caused by exercise are temporary, and they need to pay close attention and make sure they are not exercising too vigorously if the ambient temperature is high. NURSING ISSUES Multiple sclerosis can have a profound impact on physical and psychological health. Nursing care of the patient with MS should focus on the needs of the patient in those two areas. The status of the physical health of the patient with MS can vary from day to day and change over time, as well. It is important to ascertain, with the patient’s input, what the patient wants/needs to do in terms of physical activity. This information should be balanced with information about the patient’s capabilities for physical activity. It is important to stress that these are capabilities, not limitations. Certainly, the patient with MS may not be able to do everything he/she wants to do; the disease can put limits on physical activity. But with careful planning and assistance, the patient should be able to maintain a level of activity that is satisfying and allows for good health. Help the patient see the possibilities, not just the limitations. Help the patient see these issues as challenges that can be solved, not just as problems to be endured. Specific issues that patients may need advice/assistance with include: ambulation, bowel/bladder issues, skin integrity, fatigue, energy expenditure and conservation, and exercise. The psychological health of the patient with MS can be fragile – and understandably so. The patient has a disease that cannot be cured, progresses, and can cause physical pain and disabilities and serious emotional issues. There is no easy way for providing emotional/psychological support for the patient with MS. It is not the role of the nurse to substitute as a professional counselor. But the nurse can help by encouraging the patient with MS to verbalize his/her feelings and to encourage the patient to seek help. INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS Multiple sclerosis is a disease that must be managed on a day-to-day basis. Patient education and active participation by the patient in his/her own care is very important. Patients need to have the ability to recognize a relapse and have a plan if one occurs. Patients must be aware that there are many, many treatment options that can help them cope with the disease. No one has to suffer. Patients must be aware that MS causes physical signs and symptoms, but also causes emotional and social problems. There are medical issues associated with MS, but also issues of managing the challenges to day-to-day living, e.g., nutrition, exercise, ambulation, transportation, etc. MS. Patients need to know that there are a lot of resources available to help them with these challenges of living with MS. One good source of help is the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, www.nationalmssociety.org, 1-800-344-4867 REFERENCES 1. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 2. Noonan CW, Williamson DM, Henry JP, Indian R, Lynch SG, Neuberger JS, et al. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in 3 US communities. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2010;7: 1-8. 3. Lünemaann JD, Kamradt T, Martin R, Münz C. Epstein-Barr virus: Environmental trigger of multiple sclerosis? Journal of Virology. 2007;81:6777-6784. 4. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 5. Lipsy RJ, Schapiro RT, Prostko CR. Current and future directions in MS management: key considerations for managed care pharmacists. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2009;15:S1-S17. 6. McFarland HF, Martin R. Multiple sclerosis: a complicated picture of autoimmunity. Nature Immunology. 2007;8:913-919. 7. Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9:393-407. 8. Healy BC, Ali E, Guttmann CRG, Chitnis T, Glanz BI, Buckle G, et al. Smoking and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:858-864. 9. Hernán MA, Olek MJ, Ascherio A. Cigarette smoking and incidence of multiple sclerosis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154:69-74. 10. Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Tardieu M, Suissa S. Parental smoking at home and the risk of childhood-onset multiple sclerosis in children. Brain. 2007;130;2589-2595. 11. Healy BC, Ali E, Guttmann CRG, Chitnis T, Glanz BI, Buckle G, et al. Smoking and disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:858-864. 12. Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Clinical implications of possible role of vitamin D in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 2009;256:1468-1479. 13. Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Clinical implications of possible role of vitamin D in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology. 2009;256:1468-1479. 14. Lünemaann JD, Kamradt T, Martin R, Münz C. Epstein-Barr virus: Environmental trigger of multiple sclerosis? Journal of Virology. 2007;81:6777-6784. 15. DeLorenze GN, Munger KL, Lennette ET, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Ascherio A. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis: evidence of association from a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Archives of Neurology. 2006;63:839-844. 16. Levin LI, Munger KL, Rubertone MV, Peck CA, Lennette ET, Speigelman D, Ascherio A. Temporal relationship between elevation of Epstein-Barr virus antibody titers and initial onset of neurological symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2496-2500. 17. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 18. Sawcer S. The genetic aspects of multiple sclerosis. Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology. 2009;12:206-214. 19. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 20. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 21. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 22. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 23. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, Rice GP, Muraro PA, Daumer M, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis, a geographically based study 10: relapses and longterm disability. Brain. 2010;133:1914-1929. 24. Spain RI, Cameron MH, Bourdette D. Recent developments in multiple sclerosis therapeutics. BMC Medicine. 2009;7:74 25. Spain RI, Cameron MH, Bourdette D. Recent developments in multiple sclerosis therapeutics. BMC Medicine. 2009;7:74 26. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York.McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 27. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 28. Lipsy RJ, Schapiro RT, Prostko CR. Current and future directions in MS management: key considerations for managed care pharmacists. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 2009;15:S1-S17. 29. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 30. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, Rice GP, Muraro PA, Daumer M, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis, a geographically based study 10: relapses and longterm disability. Brain. 2010;133:1914-1929. 31. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 32. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 33. Spain RI, Cameron MH, Bourdette D. Recent developments in multiple sclerosis therapeutics. BMC Medicine. 2009;7:74 34. Myhr KM, Mellgren SI. Corticosteroids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavia. Supplement. 2009;189:73-80. 35. Martinelli V, Rocca MA, Annovazzi P, Pulizzi A, Rodegher M, Boseschi FM, et al. A short-term randomized MRI study of high-dose oral versus intravenous methylprednisolone in MS. Neurology. 2009;73:1842-1848. 36.Burton JM, O’Connor PW, Hohol M, Beyene J. Oral versus intravenous steroids for treatment of relapses in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. Jul 8 (3); CD006921. 37. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 38. Coyle PK. Disease-modifying agents in multiple sclerosis. Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology. 2009;12:273-282. 39. Coyle PK. Disease-modifying agents in multiple sclerosis. Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology. 2009;12:273-282. 40. Applebee A. Panitch H. Early stage and long-term treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon beta. Biologics. 2009;3:257-271. 41. Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, Kinkel RP, Brownscheidle CM, Murray TJ, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. CHAMPS Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:898-904. 42. Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Ruddick RA, Herndon RM, Richert JR, Salazar AM, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis: The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Annals of Neurology. 1996;39:285-294. 43. Applebee A. Panitch H. Early stage and long-term treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon beta. Biologics. 2009;3:257-271. 44. Kappos L, Polman CH, Freedman MS, Edan G, Hartung HP, Miller DH, et al. Treatment with interferon beta-1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology. 2006a;67:1242-249. 45. Coyle PK. Disease-modifying agents in multiple sclerosis. Annals of the Indian Academy of Neurology. 2009;12:273-282. 46. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 47. Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, Ford CC, Goldstein J, Lisak RP, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a Phase III multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1995;45:1268-1276. 48. Comi G, Fillipi M, Wolinsky JS. European/Canadian multi-center, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the effects of glatiramer acetate on magneticresonance imaging-measure disease activity and burden in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. European/Canadian Glatiramer Acetate Study Group. Annals of Neurology. 2001;49:290-297. 49. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 50. Dangond F. Mutiple Sclerosis. eMedicine. April 14, 2010. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199. Accessed August 7, 2010. 51. Elkhalifa AS, Weiner HL. Cyclophosphamide treatment of MS: Current therapeutic approaches and treatment regimens. The International Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;17:12-18 52. Elkhalifa AS, Weiner HL. Cyclophosphamide treatment of MS: Current therapeutic approaches and treatment regimens. The International Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;17:12-18 53. Casetta I, Iuliano G, Filipinni G. Azathioprine for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007Oct 17 (4);CD003982. 54. Invernizzi P, Benedetti MD, Poli S, Monaco S. Azathioprine in Multiple Sclerosis. Mini- Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;9:919-926. 55. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 56. Hauser SL, Goodin DS. Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York, New York. McGrawHill;2008:2611-2620. 57. Chwastiak LA, Ehde DM. Psychiatric issues in multiple sclerosis. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 20027;30:803-817. 58. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Fonareva I, Tasch ES. Treatment of depression for patients with multiple sclerosis in neurology clinics. Multiple Sclerosis. 2006;12:20-208. 59. Chwastiak LA, Ehde DM. Psychiatric issues in multiple sclerosis. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 20027;30:803-817. 60. Mohr, DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE, et al. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavioral, supportive expressive group psychotherapy and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:942-949. 61. Penner IK Calabrese P. Managing fatigue: Clinical correlates, assessment procedures and therapeutic strategies. International Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;17:28-34. 62. Penner IK Calabrese P. Managing fatigue: Clinical correlates, assessment procedures and therapeutic strategies. International Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;17:28-34. 63. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Lipert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. Journal of Neurology. 2009;256:645-650. 64. Rammohan KW, Rosenberg JH, Lynn DJ, Blumenfeld, AM, Pollak CP, Nagaraja HN. Efficacy and safety of modafanil (Provigil®) for the treatment of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a two centre phase 2 study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2002;72:179-183. 65. Dalgas U, Ingemann-Hansen T, Stenager E. Physical exercise and MS – Recommendations. International Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2009;16:5-11.