* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download the functioning and well being of persons who seek treatment for

Addiction psychology wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Deinstitutionalisation wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Lifetrack Therapy wikipedia , lookup

Mental health professional wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric survivors movement wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Homelessness and mental health wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Substance dependence wikipedia , lookup

List of addiction and substance abuse organizations wikipedia , lookup

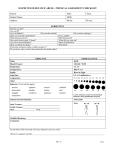

THE FUNCTIONING AND WELL BEING OF PERSONS WHO SEEK TREATMENT FOR DRUG AND ALCOHOL USE MICHAEL D. STEIN* Rhode Island Hospital, Brown School of Medicine KEVIN P. MULVEY Urban Health Insitiute, Department of Public Health, Boston ALONZO PLOUGH Department of Health and Hospitals, Boston JEFFREY H. SAMET Section of General Internal Medicine, Boston City Hospital Boston University School of Medicine, Boston ABSTRACT: We assessed the reliability of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (SF-20) in a heterogeneous group of persons seeking drug and alcohol treatment. Patients (n = 2688) seeking detoxification and treatment at four intake sites for Addiction Treatment in Boston, Massachusetts, received all components of the SF20 including physical, role, and social functioning; mental health; health perception and bodily pain. The primary drugs used were alcohol 38%, cocaine 38%, heroin 24%. Reliability coefficients for the MOS scales ranged from 0.70 to 0.92. Users of these three drugs had similar profiles among the health components. Sociodemographic characteristics in combination explained 2-7% of score variance. Alcohol and other drug use had little effect on physical or role function scores. Health perception and pain subscale scores were low. We conclude the MOS survey is a reliable measure of function and well being in this population. Like other chronic diseases, alcohol and drug use have powerful effects on quality of life. *Direct all correspondence to: Michael D. Stein, Division of General Internal Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital, 593 Eddy Street ,Providence, RI 02903 < [email protected]>. JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE, Volume 10, pages 75-84. Copyright © 1998 by Ablex Publishing Corporation All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. ISSN: 0899-3289 76 JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Vol. 10/No. 1/1998 INTRODUCTION Psychoactive substance use disorders involving illicit substances as well as alcohol are diagnosed using clinical criteria that delineate problems in health and functioning (Morse et al., 1989; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). It is estimated that drug abuse treatment would be appropriate for nearly six million Americans who are dependent on or abuse drugs (Gerstein and Lewin, 1990). The complications of drug-taking are well known and include medical problems, as well as problems with employment, criminal behavior and family relations. While persons with drug problems constitute a heterogeneous group, people most often voluntarily enter treatment as a way to manage physical, mental or social problems. Treatment outcomes in turn have reflected this heterogeneity and have been described as "multidimensional," meaning drug abstinence may not be associated with improvement in psychiatric, general psychosocial and physical health simultaneously (McLellan et al., 1981). The primary goal of health care for persons with chronic conditions is to maximize function and well being in everyday life. Without adequate measures, health care providers cannot evaluate the impact of various chronic conditions, nor the effects of interventions. While the direct biologic effects of alcohol, heroin and cocaine have been studied and measures of addiction severity have been developed, the use of a short, standardized wellbeing scale that can be applied to persons with drug problems has not been studied (Gerstein and Lewis, 1990; Institute of Medicine, 1990; McLellan, Luborsky, Woody, and Druley 1980). Such an instrument would provide health care providers and policy-makers with a global outcome measure for this population to gauge the disruption in well-being caused by drug problems. We applied the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (MOS-20), a widely used assessment of patient experience, to a large group of community-based persons seeking treatment for drug problems (Stewart, Hays, and Ware, 1988)). The purposes of our study were to: 1) assess the internal consistency of the scales of the broadly used MOS instrument in this population and 2) to compare the mean MOS scores among persons who use different drugs. METHODS Participants evaluated for drug and alcohol treatment between 3/1/92 and 7/31/93 at any of the four assessment and triage central intake sites for addiction treatment serving the City of Boston and funded by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Target Cities Program were eligible for evaluation. Approximately one-quarter of all Boston public substance abuse detoxification and treatment program patients (n = 16,259) were evaluated at these sites during the study period. Our cross-sectional study sample included 3378 subjects receiving primary care assessment at the central intake site. Individuals seeking detoxification and treatment may not have received a primary care assessment if they were too intoxicated to answer a health assessment, or if the nurse assigned to perform the assessment was already assessing another new intake. Those included in the sample were less likely to be female (28% vs. 32%), white (38% vs. 44%) and alcohol abusers (38% vs. 45%) than persons who did not receive this assessment as part of their central intake evaluation. Reliability of SF-20 77 Medical information was obtained during intake in a standardized interview with a nurse or nurse practitioner at the four intake sites. Measured sociodemographic characteristics included age, race (white, african-american, other), gender, prior intravenous drug use, years of education, self-report of primary drug currently used (alcohol, cocaine, heroin, other) and history of prior detoxifications. Subjects were also asked their medical history, including the presence of chronic medical conditions--human immunodeficiency virus infection, asthma, chronic obstructive lung disease, cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cancer, hepatitis, tuberculosis--or acute conditions such as celhilitis, septic arthritis, sexually transmitted diseases or pneumonia. To study the specific effects of drug use on quality of life, we excluded from all analyses those persons stating any of the above listed chronic medical conditions (n = 690), which might influence function and well-being (Stewart et al., 1989; Wachtel et al., 1992). The final study sample size was 2688. All component items (20 questions) of the MOS Short Form Health Survey were included in the interview (Appendix 1). The survey evaluates six dimensions of health status: physical functioning (items 1 through 6), role functioning (items 7 and 8), social functioning (item 9), mental health (items l0 through 14), health perception (items 15 through 19), and pain (item 20). The survey was conducted by interview rather than by self-administration. Therefore, the second person ("you") replaced the first person ('T') where applicable. The six resulting scales range in points from 0 to 100, the higher values indicating better health. Assessment of the reliability of the MOS Short Form Health Survey for our study sample was conducted using the method of Stewart et al. (Stewart, Hays, & Ware, 1988; Stewart et al., 1989). The Cronbach alpha was used to measure the internal consistency reliability of the four multi-item scales. The value of alpha depends on the average correlation among the various items and on the number of items in the scale. Pearson correlations were used to assess correlations among the six domains' health scores. The unique effects of all collected sociodemographic characteristics on MOS scores was assessed using 6 separate multivariate linear regression models each including the full sample in which each subscale score served as the dependent variable and the independent variables included gender, race, age, education and needle use (drug injection). RESULTS During the study period, 2688 subjects were interviewed. Respondents' mean age was 33; 73% were male; 37% were white. Twenty-seven percent reported use of intravenous drugs and 59% had completed high school. The primary drugs used included alcohol (38%), cocaine (38%) and heroin (24%). Alcohol users were older (36 vs. 31 (cocaine) vs. 33 (heroin) years old) and more likely to be white (53% vs. 19% vs. 37%). Alcohol users were also slightly more likely to have had prior detoxification (70% vs. 65% vs. 69%). Reliability coefficients (Cronbach alpha) were obtained for the four multi-item health scales in our study patients. Coefficients ranged from 0.70 for the five-item mental health scale, to 0.92 for the two-item scale of role functioning. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) among the various scores were similar to those obtained from the general outpatient sample, ranging from .15 for the correlation between pain and social function to 0.60 for 78 JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Vol. 10/No. 1/1998 TABLE 1 Reliability Coefficients and Correlation Coefficients among Health Measures Physical Function Physical Function Role Function Social Function Pain Mental Health Health Perception Notes. 0.90 0.60 0.22 -0.25 0.18 0.20 Role Function 0.92 0.25 -0.32 0.25 0.28 Social Function -0.15 0.34 0.24 Pain --0.28 -0.33 Mental Health Health Perception .70 0.45 .86 Figures in Bold representreliability coefficients. the correlation between physical function and role function. The single item social function scale had a low correlation with other scales. The physical and role function scales correlated substantially; health perceptions correlated substantially with mental health. All correlations were statistically significant (p < .001). Adjusted effects of the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents were estimated using multivariate regression models with the six health scores as separate dependent variables (Table 2). R 2 values showed that between 2% and 7% of the variance could be explained by these combinations of characteristics. The constant for each scale represents the theoretic score achieved by a subject who would have been in the referent category for all the variables listed. Age had a significant impact on all health scores except mental health. Although the reported coefficients (parameter estimates) appear small, they represent a decrement for each 1 year increase in age. Thus, a ten-year increase in subject age is associated with a 9.4 point decrease in role function. Controlling for all covariates, men scored better in physical function, social function, mental health, but worse in pain than women. Race had an impact on health perception, social function and mental health. Injection of drugs had no significant effect on any health score. In Table 3, scores of persons seeking drug and alcohol treatments were compared with those of ambulatory patients overall and those of patients with chronic medical conditions published in the Medical Outcomes Study (Stewart et al., 1989). Scores were remarkably TABLE 2 Change in Health Scores by Sociodemographic Variables Variables Male White Black Age Education Needle use Constant R2 Notes. MOS SCALE Health Physical 0.42 1.04 3.45* -0.38 0.54 -0.28 60.80 .060 *=P<.05**=P<.OI 2.69* 0.46 0.82 -0.67** 1.41 ** 0.54 96.80 .059 Role 1.70 -0.48 2.60 -0.94** 0.74* 0.01 95.10 .070 Social 3.55* 3.88 8.00** -0.27** -0.18 0.31 73.10 .022 Mental 2.70* -2.91 3.20* -0.10 0.24 0.15 54.90 .04 1 Pain -4.84** 2.59 -4.24 0.47** -0.84 -0.17 41.80 .042 79 Reliability of SF-20 TABLE 3 SF-20 Scores in Persons with Substance Abuse Compared With Results from the Medical Outcomes Study Alcohol (n = 919) Cocaine (n = 916) 85 77 66 48 47 32 89 86 70 52 52 30 Physical Function Role Function Social Function Pain Mental Health Health Perception Note. Heroin No Chronic (n = 591) Condition* Diabetes* 88 80 62 46 49 38 86 87 92 78 72 74 78 78 87 77 60 74 Heart Failure* 64 59 81 73 59 73 * = (Stewartet al. 1989). similar comparing persons seeking drug and alcohol treatment by primary drug used across the six health concepts. High scores were found in physical function and role function; the score for social function and health perception was lower than that found in all other chronic diseases (unadjusted for sociodemographic characteristics). The scores in the areas of mental health and pain were also lower for persons seeking drug and alcohol treatment than for any other chronic disease. DISCUSSION The MOS Short Form Health Survey exhibited similar reliability and correlation coefficient values for persons seeking drug and alcohol treatment to those found in other samples (Stewart et al., 1989). This is the first report to provide comparative information on functioning in patients with substance abuse disorders and patients with other chronic conditions using a consistent measurement technique. In particular, mean SF-20 dimension scores for social functioning, mental health, health perception and pain were substantially lower than mean SF-20 scores reported for other chronic diseases (Stewart et al., 1989). Alcohol and other drug use had little effect on physical function in this generally young population. Modestly lower scores were noted in role function for persons seeking treatment consistent with their frequent inability to pursue their work and normal activities. Scores were generally low in the realm of social functioning where drug and alcohol use may be socially isolating, or may be surreptitious and concealed from friends or close relatives. The preservation of role function among drug and alcohol users was surprising. The role functioning questions in the SF-20 refer to "health" problems limiting work, school or social activities. It is possible that respondents interpreted "health" in these questions as physical health, and with few physical health problems, thereby scored high on role function. If questions had been reworded (e.g., "Do your alcohol/drug problems keep you from..."), responses may have been different. Still, our results have implications for substance abuse screening by primary care providers. Health care providers may be awaiting clues or "red flags" such as physical decline to alert them to patient substance abuse. These clues may be absent in many patients who, as shown here, seem to be functioning quite well in these health dimensions even when they seek drug or alcohol treatment. 80 JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Vol. 10/No. 1/1998 Low mental health scores were not surprising in this population, although the extent of disturbances was notable. High rates of psychiatric symptoms have been observed in alcohol, cocaine, and heroin-dependent populations (Ross, Glaser, and Germanson, 1988). Affective disorders, personality disorders, and anxiety disorders are widespread among persons who seek alcohol and other drug treatment (Ross et al., 1988; Regier et al. 1990, Rounsaville, Anton, Carroll, Buddle, Prosoff, and Ganin, 1991). Because this study did not conduct psychiatric diagnostic assessments, it is possible that the low scores were the result of mental illness rather than substance abuse per se. Whether psychiatric symptoms are a cause or an effect of psychoactive substance use remains unclear. If an individual becomes dysphoric, they might increase drug use to relieve the dysphoria and yet may be further depressed because of the increased drug use. Clearly, given the degree of mental health disruption, effective methods for evaluating and treating psychiatric disorders for all persons entering alcohol and drug treatment is crucial. In addition, as has been discussed elsewhere, health care providers who detect psychiatric disorders should screen for substance abuse (Ross et al., 1988). Women scored worse than men in the areas of mental health and social function perhaps because women drug and alcohol users have fewer social supports than men (O'Connor, Samet, & Stein, 1994). A similar effect of gender has been reported in other populations using the SF-20 (Stewart et al., 1988). Older patients had lower scores across all health dimensions. This unexpected finding may be due to longer substance use histories among the older subjects, and corresponding loss of hope or support. Our findings also highlight severe pain reporting as an important measure of ill health for this population. While the location or duration of the pain is not specified by our interview methods, pain symptoms appear to be particularly troublesome for persons who seek drug and alcohol treatment as compared to other persons with chronic conditions. This result confirms what is familiar to clinicians who often see drug users for pain-related complaints (O'Connor et al., 1994). In part, the pain noted here may be due to withdrawal symptoms. In addition, certain categories of drug users have been noted to have a lower pain threshold than non-addicts (Ho and Dole, 1979). There is also a high prevalence of physical and sexual abuse in this population, traumas which themselves may be associated with altered pain perception (Scarinci, McDonald-Haile, Bradley, and Richter, 1994). Certainly, continued drug use may divert attention from pain symptoms and at the time drug treatment is sought, patients may become vigilant of their pain. Limitations There are several limitations to this study. First, the population studied includes only public substance abuse treatment program patients. These persons tend to be uninsured or underinsured and therefore may not seek treatment until drug-related complications arise. We did not study what factors influenced individuals to seek treatment. Second, persons were interviewed at the time they sought drug treatment, and this timing of presentation, at the time of particular life crises, may be reflected in lower quality of life scores (Chitwood, 1985). Future work might compare measures at entry and after treatment. Third, we had no diagnostic assessment that differentiated substance abuse and substance dependence using DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Nonetheless, the great majority of the cohort had chronic and heavy use of drugs (63% had prior detoxification) and Reliability of SF-20 81 self-perceived drug problems that required treatment. Fourth, the SF-20 is more commonly self-administered than used as part of an interview. Fifth, while construct validity is an equally important concern, reliability is the focus of this study. Sixth, because we excluded from this study persons with self-reported medical illness our results are likely to overestimate the functioning and well being scores of persons seeking drug and alcohol treatment; lower scores would be expected for persons with committant medical problems. Finally, despite similar reliability estimates, differences in sample characteristics (e.g. sociodemographics) cannot be adjusted for here, so that comparisons of mean scores with patients with chronic medical conditions should be viewed cautiously; they are included to give a sense of powerful effect on well being of drug and alcohol problems. While we divided our analyses by type of drug primarily used, individuals in this study may have been using multiple drugs contemporaneously. Multiple drug use could lead to more severe adverse impact on quality of life than single drug use, and this study did not have complete list of all drugs recently used. The severity of the alcohol and drug problem has been shown to be associated with psychiatric disorders, but our study was limited by the lack of concurrent measures of drug use severity using existing scales. The majority of variance found here in functioning and well being remains unexplained. Other predictors of these outcomes that were not assessed here such as disease severity, duration of drug abuse and medical or psychiatric care previously received might explain part of this variance. While there are no agreed upon standards to judge the meaning of differences in health status scores, previous work suggests that a difference of greater than 20 points may be a benchmark for significant clinical impact of a chronic medical condition on function (McHorney, Ware, and Raczek, 1993). Drug abuse remains an intractable American problem that is intertwined with other social crises including the spread of infectious diseases, crime, violence and neonatal drug exposure. Alcohol and illicit drug use costs society up to 280 billion dollars a year (Angell and Kassirer, 1994). Given the growing use of Medical Outcome Study Instruments across disease states and the high reliability of the SF-20 for alcohol and drug users, this short questionnaire may prove useful when evaluating the well being of drug users, guiding their use of services, predicting outcomes, or measuring improvement in functioning. Appendix to follow 82 JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Vol. 10/No. 1/1998 APPENDIX Medical Outcome Study, Short Form Health Survey (Modified~ee Methods) This set of questions concems some problems you may have to deal with because of your illness. Has your illness limited you in: (check one box on each line) Limited for More Limited for 3 Not Limited Than 3 lidos. Mos. or Less at All Physical Functioning 1. The kinds or amounts of vigorous activities you can do, like lifting heavy objects, running or participating in strenous sports: 2. The kinds or amounts of moderate activities you cando, like moving a table, carrying two full bags of groceries or bowling: 3. Walking uphill or climbing 10 steps without resting: 4. Bending or lifting or stooping: 5. Walking oneblock: 6. Eating, dressing, bathing or using the toilet: Role Functioning 7. Does your health keep you from working at ajob, doing work around the house or going school? 8. Have you been unable to do certain kinds or amounts of work, housework or schoolwork because of your health? 1 2 3 [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ [ [ [ [ [ [ [ [ ] [ ] [ ] [ [ ] [ ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] Please check the box for the one answer that comes closest to the way you have been feeling during the past month. All Most A Good Some A Little None of the of the Bit of the of the of the of the Time Time Time Time Time Time Social Functioning 9. How much time has your health limited your social activities (like visiting with friends or close relatives)? 10. How much time have you been a very nervous person? 1 I. How much time have felt calm and peaceful? 12. How much time have you felt downhearted and blue 13. How much time have you been a happy person? 14. How often have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? 1 2 3 4 5 6 [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] {] [] l] [] [] [] l] [l [l [] [] [] [] [l [} [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] Reliability of SF-20 83 Health Perceptions 15. In general, would you say [ ]Excellent [ ]VeryGood your health is: [ ]Good [ ]Fair [ ]Poor Please check the box that best describes whether each of the following statements is true or false for you. (check one box on each line) Definitely True 16. You aresomewhatill: 17. You areashealthyasanybody you know: 18. Your healthisexcellent 19. You have been feeling bad lately: Mostly True Not Sure Mostly False Definitely False 1 2 3 4 5 [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] Moderate [ ] Severe Pain 20. In the past month, have [ ] Yes you had any bodily pain? If yes, was the pain: [ ] Very Mild [ ] No [ ] Mild REFERENCES American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, DDM-4, 1994. Angell M, Kassirer J P: Alcohol and other drugs--toward a more rational and consistent policy. New England J Med 331: 537-9, 1994. Chitwood DD: Patterns and consequences of cocaine use In J. J. Kozel, & E. H. Adams (Eds.). Cocaine use in America: Epidemiologic and clinical perspectives(NIDA Research Monograph 91). DHHS 85-1414, 1985, p p . l l l - 1 2 9 . . Gerstein DR, Lewin, LS: Treating drug problems. New EnglandJMed 323: 844--48, 1990. Ho A, Dole VP: Pain perception in drug-free and in methadone-maintained human ex-addicts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 162: 392-95, 1979. Institute of Medicine. Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990. McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE: The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care 31: 247-63, 1993. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, Druley KA: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. J Nervous and Mental Disease 168: 26-33, 1980. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody, GE, O'Brien CP, Krun R: Are the addiction-related problems of substance abusers really related? J Nervous and Mental Disease 169: 232-39, 1981. Morse RM, Flavin DK, O'Brien CP, Krun R: The definition of alcoholism. J Am Med Assoc 268: 1012-14, 1992. O'Connor PG, Samet JH, Stein MD: Management of hospitalized intravenous drug users. Role of the internist. Am JMed 96: 551-58, 1994. 84 JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Vol. 10/No. 1/1998 Regier DR, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke, DZ: Comorbidity of mental disorders and other drug abuse: Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA 264: 2511-18, 1991. Ross HE, Glaser FB, Germanson T: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alcohol and other drug problems. Arch of General Psychiatry 45:1023-31, 1988. Rounsaville BT, Anton SF, Carroll KM, Budde D, Prosoff BA, Ganin FF: Psychiatric diagnosis of treatment seeking cocaine abusers. Arch of General Psychiatry 48: 43-51, 1991. Scarinci IC, McDonald-Haile J, Bradley LA, Richter JE: Altered pain perception and psychosocial features among women with gastrointestinal disorders and history of abuse: a preliminary model. Am J of Med 97: 108-18, 1994. Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells R, Rogers WH, Berry SD, McGlynn EA, Ware JE: Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAm MedAssoc 262: 907-13, 1989. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware, JE: The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 26: 724-35, 1988. Watchel T, Piette J, Mor V, Stein M, Fleishman J, Carpenter C: Quality of life in persons ith human immunodeficiency virus infection: Measurement by the Medical Outcomes Study instrument. Annals of lnternal Med 116: 129-37, 1992.