* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

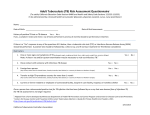

Download Initiative of Central TB Division Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript