* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Economic Developments in Portuguese

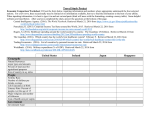

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript