* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Nature of Human Communication

Survey

Document related concepts

Face negotiation theory wikipedia , lookup

Philosophy of history wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic interactionism wikipedia , lookup

Neohumanism wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

Network society wikipedia , lookup

Tribe (Internet) wikipedia , lookup

Symbolic behavior wikipedia , lookup

Parametric determinism wikipedia , lookup

Origins of society wikipedia , lookup

Coordinated management of meaning wikipedia , lookup

Anxiety/uncertainty management wikipedia , lookup

Differentiation (sociology) wikipedia , lookup

Development Communication and Policy Sciences wikipedia , lookup

Cross-cultural communication wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

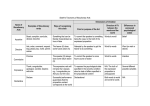

The Nature of Human Communication The nature of human communication Philosophically, “the purpose of words is to give the same kind of publicity to thought as is claimed for physical objects” (Russell, 1979, p. 9). Pragmatically, “Communication is the management of messages for the purpose of creating meaning” (Frey et al, 1991). According to Kreps (1990) human communication occurs when a person responds to a message and assigns meaning to it. Specifically, we should be careful to define a message as any symbol or thing that people attend to and create meanings for in the communication process. Meanings are the mental images created to help us interpret what happens around us so that we develop an understanding. Human communication is irreversible, bound to the context in which it occurs (i.e. time and place), and arises within relationships between communicators. Acceptance arises from the apprehender’s choices, not the initiator’s intentions. Participants to a communicative event take part in a process of creating shared meaning. First we interpret the situation, then act, influencing one another. We all have concerns, in response to each of which, we construct an inner representation of the situation that is relevant to that concern. The appreciative system (Vickers, 1983) is a pattern of concerns and their simulated relevant situations, constantly revised and confirmed by the need for it to correspond with reality sufficiently to guide action, to be sufficiently shared among people to mediate communication, and to be sufficiently acceptable for a ‘good’ life. The appreciative system is thus a mental construct, partly subjective, largely intersubjective (i.e. based on a shared subjective judgement), constantly challenged or confirmed by experience. The initiator begins the process of communicating with an intention, whilst the apprehender is drawn into a joint system of communication when they try to interpret the other person’s intention and the situation, and from this derive a meaning for the event. Vickers would term this appreciation. Only if the appreciative mind classifies the situation as changeable or in need of preservation, does the person devise possible responses and evaluates them with criteria determined by their other concerns. Thus ‘problems’ are discerned, and ‘solutions’ sought. Action may or may not follow. Vickers (1983) distinguished seven overlapping and coexisting ascending levels of trust and shared appreciation (described in Table 1 below). 1. Violence 2. Threat Erodes trust and evokes a response to contain it and to abate it, but has no specific communicative purpose The conditional ‘do it or else’ – involves trust only to the extent that the threatened needs to believe both that the threatener can and will carry out a threat unless the condition is fulfilled and to fulfil the condition will avert the threat 3. Bargain 4. Information 5. Persuasion 6. Argument 7. Dialogue Involves a greater shared assumption – each party has to be confident that the other regards the situation as a bargain – the attempt to negotiate an exchange on terms acceptable to all the parties – each must believe that the other parties can and will carry out their undertakings if agreement is reached – each is free to make not merely an acceptable bargain but the best they can, or to withdraw from the negotiation The receiver must not only trust that the giver’s competence and reliability, they must also be assured that giver’s appreciative system corresponds sufficiently with their own to ensure that what is received fits the receiver’s needs. Even if it does, it will, to some extent, alter the setting of their appreciative system The giver actively seeks to change the way in which the other perceives some situation and thus to change the setting of their appreciative system more radically When the process is mutual, each party strives to alter the other’s view whilst maintaining their own Each party seeks to share, perhaps only hypothetically, the other’s appreciation and to open their own to the other’s persuasion with a view to enlarging both the approaching mutual understanding, if not shared appreciation Table 1: Levels of human communication (Vickers, 1983) Cognitive bias Left-hemisphere, lineal biased models (e.g. Shannon & Weaver’s ‘communication theory’) ignore the surrounding environment (context) in promoting a pipeline hardware container for software content. This wrongly assumes that communication is a literal matching rather than a making of meaning. Birdwhistell (1970), on the other hand, defines communication as the dynamic or processual aspect of social structure, and as that behavioural organisation which facilitates orderly multisensorial interaction. Marshall McLuhan was one of the first to seriously consider differences in brain function (see McLuhan and McLuhan, 1988) after being contacted by a neurology researcher who thought that there might be a cerebral hemispheric basis for some of the dichotomies of McLuhan’s work (linear-sequential, or simultaneous-spatial, for example). He suggested a hemispherical dominance in the human brain. Each hemisphere of the brain is thought to specialise in processing different kinds of information and dealing with different kinds of problems. The left brain deals with the more logical/verbal, whilst the right side is more intuitive/creative. According to McLuhan, a private, left-brain ‘point of view’ became impossible with the invention of the phonetic alphabet because both writer and reader were separate from the text. The result was ‘civilised’ private detachment. The emergence of the alphabet elevated the importance of the left brain functions and led to mathematics, science and philosophy. Fragmenting and civilising technologies and tools favour the left brain. The dual hemispheres of the human brain might hold some relationship to understanding communication media, thought McLuhan and others, including Gerald Goldhaber and Neil Postman. Covey (1989) refers to our developing understanding of the specialisation of the brain’s hemispheres as brain dominance theory. Covey concludes that personal effectiveness comes from managing from the left-brain, and leading from the rightbrain. Nobel Prize winner Roger Sperry carried out much of the scientific work in this field. Buzan (1974) also promoted the idea that basic thought processing abilities are located in a particular part of the human brain (Table 2). LEFT SIDE: visual Numbers Lists Order Attention to detail Mathematical reasoning – numbers, calculation, Logic Breaking-down into parts Time-bound Sequencing – order Analytical – measurement, abstraction Lines Words – verbal Controlled, intellectual, dominant, worldly, active Sequences RIGHT SIDE: acoustic Overview of wholes (the big picture) – holistic Rhythm Shapes Synthesis, gestalt Art Imagination Creativity, intuitive Conscience Empathy, emotional, Inspiration Day dreams Colour Spiritual, receptive Space – visual Table 2: The brain’s hemispheric specialisations (adapted from Buzan, 1974, Covey, 1989, and Gelb, 1995, McLuhan and McLuhan, 1988) Rational logical, scientific thinking is well served by the left side of the brain. Since the invention of the alphabet and print there has been left-hemisphere dominance in our culture – the activity of the right hemisphere has been suppressed. Thinking processes from the right side need to be incorporated into our thinking to give a more holistic thinking approach. Left-hemisphere dominance impacts on the way we process information, as well as on content. As Covey (1989) puts it, it would be nice to cultivate and develop the ability to have a good crossover between the sides, so that a person could first sense what the situation called for and then use the appropriate tool to deal with it. What actually happens is that we tend to use our dominant hemisphere and process every situation according to a personal left or right brain preference. Further work has shown that not everyone has such a clear-cut brain function dominance and that the functions may not always be in the same hemisphere. Whatever the location, it is the ability to realise synergy between the two modes that is of most value – logic and imagination – intuition and awareness of a larger context - in harmony (Gelb, 1995). To succeed, we all need a balanced brain! A right-brain dominant person will not get far in trying to communicate with a left-brain group by urging them to “see the big picture”. A left-brain person will not get through to a right-brain person by giving them facts and figures. A technique for balancing our thinking is mind mapping, originally developed by Buzan. This applies creative association to break out of divergent and convergent and to achieve synergistic intelligence (Buzan, 1993). Mind mapping is a graphic technique for rapid note-taking and note-making that flows like the way in which we think. Left-brain explanations of ‘communication’ are outmoded by the advent of the electronic (information) age. A right-hemisphere model of communication is necessary to rid us of the assumption that communication is a kind of literal matching rather than a resonant making of identity, meaning, and knowledge. Our ‘scientific’ models of communication are linear, logical, and sequential. Yet, we need a simultaneous, holistic, relational conception. Our thinking about managing must cease pursuit of control and location of facts and understanding to be shared. Instead we must produce and relate. Communication is a making contact between people in which meaning, identity, and knowledge are co-produced. From this we get a sense of co-presence, some degree of commonality and co-orientation. Understanding alone is rarely sufficient. The societal dimension On a philosophical level of ‘grand theory’, Jurgen Habermas has elaborated the nature of communicative action. According to Habermas (1984, 1987), acting communicatively requires the desire to participate in a process of reaching understanding. Something is uttered understandably to the hearer for them to understand. The speaker makes him/herself understandable, and then comes to an understanding with another person. This requires several conditions: The choice of a comprehensible expression so that the speaker and hearer can understand one another The speaker must have the intention of communicating a true proposition so that the hearer can share the knowledge of the speaker The speaker must want to express his/her intentions truthfully so that the hearer can believe the utterance, i.e. they can trust the speaker The speaker must choose an utterance that is right so that the hearer can accept the utterance and the speaker and hearer can agree with one another in the utterance with respect to a recognised normative background. Habermas’s work is a form of rhetorical theory, based on the ideal communication situation (system). A speech act succeeds if the relation intended by the speaker between the speaker and the hearer comes to pass and if the hearer can understand and accept the content uttered by the speaker in the sense indicated, for example as a promise, assertion, suggestion, order, etc. (Habermas, 1979). Burleson and Kline (1979, cited in Pearson, 1989) operationalised Habermas’ theory of communication by stating the requirements for real dialogue: Participants must have an equal chance to initiate and maintain discourse Participants must have an equal chance to make challenges, explanations, or interpretations Interaction among participants must be free of manipulations, domination, or control Participants must be equal in terms of power. Dialogue is characterised as a communication spirit or attitudinal orientation towards the self, others, the topic for discussion, and the situation. Dialogue requires a clash of attitudes, equality of control and initiation of the communication, the risk of one’s own point of view, and agreed rules to facilitate the process. Dialogue is contrasted with monologue in Table 3. Monologue Deception Superiority Exploitation Dogmatism Insincerity Pretence Personal display Coercion Distrust Self-defensiveness Dialogue Honesty Concern for others Genuineness Open-mindedness Mutual respect Empathy Lack of pretence Non-manipulative intent Encouragement of free expression Disclosure Table 3: Qualities of communication styles (Johannesen, 1974, cited in Pearson, 1989) Niklas Luhmann’s work offers an alternative social systemic constructionist grand theory. The ‘grand theory’ philosophies of Habermas and Luhmann present two conflicting functionalist perspectives (controversial paradigms) on social analysis (see Table 4), although both centre communication in their analysis of the relationship between subject and society and between action and structure. These functionalist theories proceed from an understanding of the whole society to an understanding of the parts of the whole (Barnes, 1995, suggests that this work is both suspect and difficult). Lifeworld rationality of Habermas Social system rationality of Luhmann Rationality & universality Differentiation - pluralism Communicative action – language Strategic action - power, money Common good, understanding, consensus Efficiency – understanding in and by communication is an exception Inter-subjective paradigm – agents acting Social systemic paradigm – system acting Strategic actions distort communication Communicants believe that they understand each other It is unethical to enter the public sphere in representing private or particular interests – the ideal speech situation is necessary for inter-subjective consensus It is functional to enter the public sphere representing special interests since no collective perspective on society exists – intersubjective understanding is based on consensus and conflict Table 4: Inter-subjective vs. Social Systemic Communication Paradigms (based on Holmström, 1996) The polarised treatment of informational vs. transformational conceptions of communication as the basis for other description and explanation is further illustrated in books that give considerable scope to discussion of Habermas’ work whilst Luhmann’s considerable body of work is rarely mentioned (see Crook et al, 1992, for example). A recent textbook on ‘theories of human communication’ (Littlejohn, 1999) gives over two pages to the work of Habermas as a Critical Theory perspective on communication, yet does not mention Luhmann at all. On the other hand, Eve et al (1997) cite Habermas on only two pages, whilst referring to Luhmann’s work on twelve pages. Luhmann views social systems as generated by people interacting through symbols. They are autopoietic, capable of self-reproduction, i.e. at least some autonomy for the system from the people who live in it (see Luhmann, 1990, and 1995, on selforganising/self-referencing systems). He defines evolution as the process of increasing differentiation of a system in relation to its environment, arguing that the mechanism for selection of one social alternative over another is “communicative success” – some types of communication are more flexible than others and allow for better adjustment to environmental conditions (Luhmann, 1982). The socialising of the human communication concept In Burr’s (1995) view, we should avoid a traditional psychological analysis, since psychology itself is based on false premises, does not address the real sources of personhood, and is oppressive in serving to uphold inequitable power relationships in an individualistic western capitalist society seen to be comprised of isolated, selfsufficient individuals relating only through cold, rational calculation of cost and benefit. Simply put, the reasons for people’s behaviour and experience are not to be found inside their heads. Explanations cannot be found by seeking structures and processes operating within the psyche of the individual person – memory, perception, motivation, emotion, attitude, and so on, are social phenomena and not private events that arise only within our own heads. The psychologist’s assumption that complex social phenomena are reducible to the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of individual actors is wrong. Constructions arise not from people attempting to communicate internal states (feelings, desires, attitudes, beliefs – stemming from their ‘personality’) but from their attempts to represent themselves or the world in a way that is liberating, legitimating, or otherwise positive for them. Luhmann (1975) is clear that psychic systems can only think – they are closed systems of consciousness. As soon as any communication takes place between people, a social system arises. Thus, we discover the reason for the polarised views of Habermas and Luhmann. Habermas thinks of communication as an act of transmitting information. Luhmann, on the other hand, defines communication as a self-referential system – the establishment of meaning an cognition is a construction of reality, not a reflection of reality. It is not that the social context of individual behaviour influences the pre-existing individual as an ‘add-on’. Rather, according to Derrida (1974), the individual is necessarily defined by its opposite term (‘not-individual’), society. The nature of things lies in the relationships between them rather than in the things themselves. Derrida shows that western thinking has been founded on the logic of binary oppositions, in which one term usually is given a privileged position over the other (for example, individual-society, mind-body, reason-emotion). For Derrida, this is typical of ideologies. We are led to believe that one side of the dichotomy has greater value than the other side, when neither can exist without the other. Derrida recommends that we discard the ‘either/or’ logic, and adopt instead a logic of ‘both/and’. Drawing on Bateson’s (1972) notion of an ‘ecosystem’, Sampson (1989) offers the relationship between individual and society as an ecosystem, for which it makes little sense to separate either: “The embedded or constitutive kind of individuality does not build upon firm boundaries that mark territories separating self and other, nor does it abandon the connectedness that constitutes the person in the first place” (1989, p. 124). Personal identity arises from interactions between people, constructed out of the discourses (of age, gender, education, sexuality, style, and so on) that are culturally available in communicating (Burr, 1995). The person is the end-product of the combination of ‘versions’ of things that are available to them: “Our identity therefore originates not from inside the person, but from the social realm, where people swim in a sea of language and other signs, a sea that is invisible to us because it is the very medium of our existence as social beings” (Burr, 1995, p. 53). Re-humanising communicating Lee Thayer (1997) wishes us to reclaim communicating as a human condition. This is largely a matter of learning how to express what others will comprehend, and to comprehend what others will express. In this, we will have learned how to communicate, and, in communicating, we will come to know. We cannot ‘impart’ to another person some idea or other that that person is not equipped to ‘understand’. Philosopher Collingwood (1940) suggested that an utterance (or a sign) is meaningful to the extent that it is the answer to a question that could in principle be formulated by the recipient (or, as Whitehead (1938) called the person who interprets the world and its messages, the “percipient”). Thus, communication occurs in knowing the question to which any utterance is the answer. “In our obsession to scientize the study of communication, we have trivialized it; we have neglected what may be the key fact in the relationship between communication and human interests. It is that any theory of communication is at once a theory of human nature.” (p. 205) “We have trivialized human communication by reducing it to the notion of “information transfer”” (Thayer, 1997, p. 202). Communication is essential to survival and prosperity. A closed social enterprise is one in which the object or the end is known, and for which the basic rules or means are also known – it has been institutionalised. An open social system is one in which the end or the object is merely desired, and for which the rules or the means are improvised. A closed social enterprise constitutes the structure of a society; an open social enterprise constitutes its anti-structure. A closed system is for preserving itself. An open system is creative and therefore destructive (Burke, 1969). In looking at the accelerating rate of change in human history, the “poetics” of communication ought to be at “the very center of one’s theoretical musings, if for no other reason than simply because the source and the limits of all change lie in the “poetics” of communication.” (Thayer, 1997, p. 26). Traditional cultures reproduce themselves in a sort of cyclical fashion by constraining what could be said about things. The ‘modern’ culture produces itself by unconstraining what can be said about things. The former is “truthkeeping”, whilst the latter is “truth-seeking” (see also Deetz, 1992, 1995, on productive and reproductive communication processes. Thayer (1997) sees that: “….. a modern society, unlike a traditional society, is not systematically a whole of which every part has the same functional relevance as every other part – as was the case with tribal societies. It is more like an ever-changing congeries of subparts, each vying with the others for dominance, for hegemony, for relevance.” (p. 33) He explains the social dynamic with a metaphor: “What brings the audience to a symphony hall is the expectation of hearing something with which they are familiar ……. What brings the audience to a jazz festival is the willingness to coproduce, with the performers, an “experience” in hybridization – that is, musical enterprise. What makes the soloist relevant is his (or her) performance. What makes the ensemble player relevant is the music. The one presages the modern, the other the traditional. These are two very different kinds of social order.” (p. 34) Thayer (1997) is clear why we should discard the informational conception of communication. Meanings are human artefacts. They do not exist in nature. The environment (which includes us) contains no information. It is what we can give to something that informs us. “What is the question, that “information” may constitute the answer?” (p. 48). By assuming something other than a scientistic posture, we can be intrigued by the possibility that communication is not primarily referential in nature, but consequential. In our ways of expressing ourselves, we create the shape and form and the characteristics and the very nature of all that we might know. And in the process, we create the nature of the knower; we create ourselves. Our contemporary (and longstanding) view of communication in Western civilizations limits us almost exclusively to the tactics of communication and to matters of ‘effectiveness’ or of ‘efficiency’. Our understanding of ‘communication’ technologies follows from the exigencies of private or common metaphors; it does not precede them. These ‘communication’ technologies are technics for the acquisition, generation, distribution, storage, and so on, of data. There is no piece of hardware that, for example, “transmits” the stuff of consciousness. The ‘information’ of consciousness is of a different order of reality from the “information” of Information Theory. There are technologies for the latter, but not even the ‘hardware’ of the human sensors is capable of accepting anything but informationless (in the human sense) data. A human must be the de facto creator of what comes into his or her consciousness – that is, that which that particular human can comprehend or can articulate. Thayer can explain why the orthodox conception of what it is to communicate does not make sense: “Our assumption, given the nature of the biases of our Western mentalit, is that one first has a mind, and merely learns how to “express” it in words, or in communication; or that one has feelings, and then merely learns how to “express” them to others, or to comprehend others’ expression of “them”; or that one first somehow “knows” something, and then merely learns how to “communicate” that knowledge to others. This is not so. Minds and feelings and attitudes and thoughts are literally communicated into existence; and then they have only that existence that their communicability permits – enables or constrains. It is not that we communicate the way we do because we are the way we are; it is that we are the way we are because we communicate (or not) the way we do.” (p. 203) “Communication, then, is the process in which we create and maintain the “objective” world, and, in doing so, create and maintain the only human existences we can have.” (p. 203)