* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download IPE1_2 - DSE | @univr.it

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

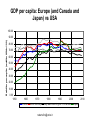

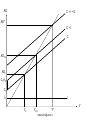

International Political Economy [email protected] Lesson 1 Section 1.1 WHAT IS THE INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY? [email protected] • Economies in which the relations with foreign plays a prominent role are said to be open. • The analysis of such economies requires that considerable attention be paid to government decisions • Particularly, this role is critical in field as: – International trade – Balance of payment and your deficit/surplus – Fiscal and monetary policy – Interest rate –… [email protected] • The discipline that analyzes the government role in economies is the Political Economy • The discipline that studies how the government decisions have effect with international trade and economic relations with rest of world is named International Political Economy (IPE) [email protected] • Economics – Microeconomics (individual decisions and behaviour) – Macroeconomics (aggregate decisions and collective behaviour) • Political Economy (economic role of government) – International Political Economy (economic role of government in international field) [email protected] Course Outline • • • • • • Quantitative Dimensions of Globalization Budget Deficit and Public Debt The Balance of Payments Political economics in Open Economy Purchasing Power Parity Interest Rate Parity [email protected] Lesson 1 Section 1.2 DATA SOURCES [email protected] IMF [email protected] World Bank [email protected] OECD [email protected] Central Banks (http://centralbank.monnaie.me/) [email protected] Federal Reserve [email protected] ECB [email protected] Eurostat [email protected] Banca d’Italia [email protected] People’s Bank of China [email protected] ISTAT [email protected] Lesson 1 Section 1.3 GDP: THE PRESENT AND NEXT FUTURE [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] GDP 14,000,000 billions US$ 12,000,000 10,000,000 8,000,000 6,000,000 4,000,000 2,000,000 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 Canada France Germany Italy Japan United Kingdom United States China [email protected] 2005 GDP 5,000,000 4,500,000 4,000,000 billions US$ 3,500,000 3,000,000 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 500,000 0 1990 Canada 1992 France 1994 1996 1998 Germany Italy 2000 Japan [email protected] 2002 2004 2006 United Kingdom 2008 China GDP 40 35 30 percent 25 20 15 10 5 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 Western Europe Oceania Asia Middle East 1990 2000 North America Eastern Europe and Central Asia Latin America [email protected] GDP Peso percentuale sul PIL mondiale 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1900 1920 Europe 1940 USA 1960 China [email protected] 1980 India Japan 2000 percentuale di PIL per area geografica rispetto al PIL mondiale GDP 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Western Europe North America Oceania Eastern Europe and Central Asia Asia Latin America Middle East [email protected] 2009 GDP contributo dei singoli paesi al PIL dell'area 80 70 15 60 50 40 30 20 10 22 4 16 3 14 12 5 6 13 9 6 14 11 12 13 12 15 19 19 18 17 14 13 13 14 1950 1960 1970 1980 10 8 15 12 20 19 14 16 15 1990 2000 2009 0 France Germany Italy Spain [email protected] United Kingdom GDP Contributo dei singoli paesi al PIL dell'area 90 80 2 70 20 3 2 40 28 6 27 39 50 5 38 23 33 7 6 23 30 6 5 7 18 15 5 18 17 15 43 20 10 5 13 60 8 4 24 24 1950 1960 19 19 23 1970 1980 1990 30 0 China India Indonesia Japan [email protected] 2000 South Korea 2009 GDP Contributo dei singoli paesi al PIL dell'area 100 90 80 70 8 8 7 7 23 25 25 22 6 5 6 3 8 4 7 5 8 6 26 28 35 35 33 33 18 16 13 10 11 12 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2009 10 12 11 18 19 21 7 6 6 5 60 50 40 30 23 20 10 22 0 1950 Argentina Brazil Chile Colombia [email protected] Mexico Venezuela GDP: BRICs 9,000,000 8,000,000 PIL in US$ 1990 PPA 7,000,000 6,000,000 5,000,000 4,000,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 1950 1960 1970 Russian Federation 1980 China [email protected] 1990 India 2000 Brazil 2010 GDP: G7 vs BRICs PIL in milioni di US$ 1990 PPA 16,000,000 14,000,000 12,000,000 10,000,000 8,000,000 6,000,000 4,000,000 2,000,000 1950 1960 1970 G-7 1980 BRICs [email protected] 1990 2000 2010 GDP per capita: Europe (and Canada and Japan) vs USA 100.00 Reddito pro-capite (reddito USA=100) 90.00 80.00 70.00 60.00 50.00 40.00 30.00 20.00 10.00 0.00 1950 1960 France 1970 West Germany 1980 Italy 1990 United Kingdom [email protected] 2000 Canada 2010 Japan GDP per capita: All vs USA Reddito pro-capite (reddito USA=100) 90.00 80.00 70.00 60.00 50.00 40.00 30.00 20.00 10.00 0.00 1950 1960 1970 1980 Western Europe Eastern Europe and Central Asia Latin America Africa [email protected] 1990 Oceania Asia Middle East 2000 2010 Lesson 2 Secion 2.1: Introduction BUDGET DEFICIT AND THE NATIONAL DEBT [email protected] • Upon completion of this chapter you should – know what's involved in calculating the structural deficit, a deficit measure designed to provide a more accurate view of the extent to which we should worry about the size of the deficit; and – recognize the circumstances in which an increase in the national debt can be viewed as a burden on future generations. • When government spending exceeds tax revenues, there is a government budget deficit, which is financed by selling bonds. • The sum of all outstanding government bonds is called the national debt, which grows each year by the amount of the budget deficit. (It would shrink if there were a budget surplus.) • Some bonds are sold to the central bank, an agent of the government, so this part of the national debt the government owes to itself; consequently, nobody worries about it. • The remaining bonds are sold to the public, augmenting the publicly held national debt • An important legacy of Keynes is that budget deficits became respectable side effects of efforts to keep an economy operating at full employment. • Keynes's intention was that deficits required to stimulate the economy when it is in recession would be offset by budget surpluses in times of full employment, ensuring that in the long run the national debt would not continually grow. Lesson 2 Section 2.2 : Recall on AD BUDGET DEFICIT AND THE NATIONAL DEBT AD AD3 AD2 AD1 Y Y1 Y2 Y3 [email protected] AD AD* AD3 AD2 AD1 Y1 Y2 Y3 Y* [email protected] Y AD AD* C+I C ADc+I ADc C0+I0 C0 I0 I YC YC+I Y* [email protected] Y AD C+I+G AD* C+I C ADc+I ADc C0+I0 C0 I0 I YC YC+I Y* [email protected] Y AD (C + I + G)inf AD** C+I+G AD* C+I C ADc+I ADc C0+I0 C0 I0 I YC YC+I [email protected] Y* Y AD (C + I + G)** AD** C+I+G ADinf AD* C+I C ADc+I ADc C0+I0 C0 I0 I YC YC+I [email protected] Y* Y** Y Lesson 2 Section 2.3: Budget deficit (causes and effects) BUDGET DEFICIT AND THE NATIONAL DEBT [email protected] Growing deficit responsabilities • Three main culprits were responsible for the growing deficit • 1. Tax decreases. – The ratio of tax revenue to GDP is about 30 percent in the United States, the lowest of all OECD countries. Canada's ratio is about 40 percent, and Sweden's is about 50 percent. • 2. Growing entitlement expenditures. – Social Security and Public Health Service expenditures cannot easily be controlled because anyone eligible is entitled to coverage. As our population ages, spending in these two categories continually increases, with politicians refusing to increase taxes to pay for it. • 3. Higher interest payments. – Because of higher interest rates and a higher national debt, interest payments as a fraction of government spending have jumped from about 9 percent to about 13 percent. Recent decreases in interest rates have alleviated this burden considerably. Budget deficit: costs and benefits • Budget deficits carry both costs and benefits for the economy. Any assessment of their desirability must weigh these costs and benefits carefully. 1. Lower unemployment 2. Public investment 3. Lower national saving 4. International implications 5. Debt monetization 6. Growing national debt • Especially, growing national debt. – Continued budget deficits increase the national debt. A growing national debt has several important implications: • a. A growing national debt means growing interest payments on that national debt. Over time, the interest payments may become a sufficiently large fraction of the government's financing needs that they render fiscal policy inflexible. Fiscal policy to attack unemployment, for example, may not be undertaken because financing is not available. • b. A growing national debt inevitably means that tax rates rise as much as politicians dare, to facilitate handling the high interest payments. Tax increases create disincentive effects, as emphasized by the supply-siders. • c. A growing national debt means that we may be placing a burden on future generations who will inherit that debt. Many view this practice as morally wrong. d. A national debt could grow to the point where it will become too large for the country to service, causing a major crisis in the economy. One way of measuring whether an economy is headed in this direction is to calculate the structural deficit. • The structural deficit is the part of the current budget that in the long run increases the ratio of the publicly held national debt to nominal GDP. • Three adjustments must be made to the current budget deficit to calculate the structural deficit: – 1. A correction is needed for cyclical effects that hinder the current deficit's ability to reflect any long-run trend accurately. For example, if GDP drops below its long-run trend average by $100, it is estimated that tax receipts fall by $25 and government spending on transfers increases by $8, so that $33 of the deficit does not correspond to long-run behavior. It should be noted that there is not a universal definition of the structural deficit. Some textbooks define it as involving only this cyclical adjustment. – 2. A correction is needed for real growth and inflation because if nominal GDP is growing the publicly held debt can grow without affecting their ratio. – 3. A correction is needed for seigniorage. Each year, an increase in the money supply is required to accommodate money demand increases, allowing the government to finance some of its deficit by printing money. This financing does not affect the publicly held debt. • Correction for cyclical effects – The economy is currently experiencing an unemployment rate greater than its long-run average, so part of the current deficit does not reflect the long-run contribution of the deficit to the national debt. • Correction for nominal growth – Nominal GDP—the denominator of the ratio of the publicly held debt to GDP—is growing, so the numerator can grow at the same rate without increasing this ratio • Correction for seigniorage. – Each year the central bank increases the money supply to accommodate the economy's nominal growth. This increase allows some of the deficit to be financed by selling bonds to the central bank (printing money) rather than to the public. These bond sales do not affect the publicly held debt and thus do not affect the ratio of the publicly held debt to GDP Budget deficit and future generations • The question of whether a burden is being passed on to future generations is best addressed by examining the capital stock that is being passed on at the same time. Let us examine this issue first by assuming only domestic borrowing and second by assuming borrowing from foreigners Domestic budget deficit • If the borrowing is domestic, then we owe the debt to ourselves, and it seems that overall there is no intergenerational burden. • This reasoning is misleading, however. • Domestic borrowing to finance a deficit crowds out some investment spending. • If the deficit spending is on capital assets such as roads and airports, it is possible that the capital stock passed on to the future generation is of more value than the investment spending that is crowded out Budget deficiti for foreigners • The great advantage of borrowing from foreigners is that crowding out can be avoided. • The foreign exchange obtained by the borrowing can be used to import more goods and services, allowing the economy to have extra output to distribute to its citizens. • In this case, however, future generations must pay interest and principal to foreigners, so it looks as though they are being burdened. • Once again, though, this conclusion depends on the nature of the deficit spending. If the government has borrowed to invest in social infrastructure that increases the economy's productivity by enough to create additional annual income sufficient to pay off the interest and principal of the debt, then the deficit cannot be said to burden future generations. Lesson 2 Section 2.4: the Twin Deficit BUDGET DEFICIT AND THE NATIONAL DEBT [email protected] USA 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1990 -10 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 General government gross debt 2002 2004 2006 Current account balance [email protected] 2008 China percent of GDP 18 13 8 3 1990 -2 1992 1994 1996 1998 General government gross debt 2000 2002 2004 2006 Current account balance [email protected] 2008 Germany 85 75 percent of GDP 65 55 45 35 25 15 5 -51991 1993 1995 1997 1999 General government gross debt 2001 2003 2005 Current account balance [email protected] 2007 2009 Italy 115 percent of GDP 95 75 55 35 15 -51990 1992 1994 1996 1998 General government gross debt 2000 2002 2004 2006 Current account balance [email protected] 2008 India 75 percent of GDP 65 55 45 35 25 15 5 -51991 1993 1995 1997 1999 General government gross debt 2001 2003 2005 Current account balance [email protected] 2007 2009 Japan 250 percent of GDP 200 150 100 50 0 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 General government gross debt 2000 2002 2004 2006 Current account balance [email protected] 2008