* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The_Decision_to_Use_the_Bomb

Survey

Document related concepts

Empire of Japan wikipedia , lookup

Aftermath of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Wang Jingwei regime wikipedia , lookup

Consequences of the attack on Pearl Harbor wikipedia , lookup

Allies of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

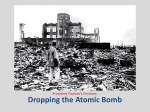

The Decision to Use the Bomb The modern nuclear arsenals and the struggle to control nuclear weaponry have brought new significance and controversy to the American use of the atomic bomb in World War II. This reading selection describes the circumstances surrounding the decision to use the atomic bomb. There is considerable debate among historians about the necessity of using the bomb to force Japan's surrender; there is perhaps even greater controversy concerning the moral principle involved in subjecting the two Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to this weapon. This latter point is raised, but not answered, at the end of the essay. World War II was the second world-wide war in less than a generation's time. The World War I had erased any romantic illusions about the nature of modern war; World War II saw the complete mobilization of entire populations and economies in the waging of the war. It was fought with grim determination on every side. In such conditions, each side carried out acts of great brutality in the frustration and necessity of achieving victory. For the first time outside a civil war, fighting spread beyond the armies to whole populations: Hitler used aerial bombing to try to break the spirit of the British; the Japanese used aerial bombing and soldiers against the Chinese civilian population; both Japan and Germany used their military forces to subdue resistance in occupied nations; and the allied forces used bombing to carry the war beyond the battle front and break the opposition of enemy populations. By the end of the war, technology had advanced to the point where such bombings were terrible: the allied bombing of Dresden killed tens of thousands of people, and the American firebombing of Tôkyô in March 1945 probably killed more than 100,000 people. During this period, wartime technology raced ahead, as each side attempted to be the first to develop the techniques and equipment that would enable it to win. Many nations sought to decipher the secrets of atomic energy, but the United States was the first to develop the ultimate weapon, the atomic bomb. Prelude to the Bomb: On April 1, 1945, the Allies invaded the southern Japanese island of Okinawa, and their victory there after bitter and bloody fighting with heavy losses on both sides proved that Japan could not win the war. It also proved, however, that invasion of the Japanese homeland would cause massive casualties on both sides. As American ground forces swept Okinawa clean of Japanese troops, the local civilians were caught in the middle. Subjected to gun fire, bombing, and infantry combat by the American advance, they were prevented from surrendering by the Japanese troops. Okinawa only served to confirm everyone's idea of how the final battle for the main islands of Japan would be fought. The surrender of Okinawa caused the Japanese cabinet to collapse and a new, pro-peace prime minister and foreign minister pressed the army to allow negotiations. The Japanese military, however, trapped in its own mystique of rigid determination and self-sacrifice in the name of the nation and emperor, insisted on strict terms. Just at this point, the atomic bomb became a reality. The first successful test of the atomic weapon was held on July l6, 1945. The United States now had the choice of using it to try to end the war in another way. All other forms of attack, from the grim battle for Okinawa to the terrible fire bombing of Japan's cities, had failed to deter the leaders in Tôkyô. Perhaps the atomic bomb would resolve the crisis without a need for invasion. President Truman, who had already left for Potsdam to meet with Churchill and Stalin, left instructions that the bomb was not to be used against Japan until after the Allies had agreed on and issued a declaration. The Potsdam Declaration of July 26, issued by the Allied powers and calling for "unconditional surrender," was not acceptable to the Japanese military, despite the declaration's threat that failure to surrender would be met by "complete destruction" of the military and the "utter devastation of the Japanese home land." Following ten days of Japanese silence, the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945, on the city of Hiroshima. The Impact on Japan: It was reported the next day to the Japanese Army General Staff that "the whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb." On August 8 the army was further rocked by the news that the Russians, who had remained neutral to Japan throughout the war, had attacked Japanese forces on the Asian mainland. But despite the prime minister's insistence that Japan must accept surrender, the army insisted on total, last-ditch resistance. The news, midway through this conference, that the city of Nagasaki had also been destroyed by another atomic bomb, did not sway them from their determination. Finally, the Japanese prime minister and his allies agreed that the only course was to have the emperor break the deadlock by expressing his view. The emperor's statement that Japan's suffering was unbearable to him and that he wished for surrender broke the military's opposition and began the process of ending the war in the Pacific. Assessing the Decision: Was it necessary to use the atomic bomb to force Japan to surrender? This is a subject of heated debate among historians. Some point to the existence of a pro-peace faction in Japan, resisting the army and growing in strength. This faction had already tried to express Japan's interest in peace through the Russians, whom they believed were still neutral. In fact, the Russians had secretly agreed at the Yalta Conference in February 1945 to attack the Japanese. Moreover, Japanese offensive capabilities were exhausted. The navy and air force were almost totally destroyed by the summer of 1945, and the Japanese islands were completely cut off from the rest of the world. The Russian attack of August 8 on Manchuria met little or no resistance. Discussion Questions 1. How did the battle over the island of Okinawa influence the decision to use the atomic bomb? 2. How would you rank, from most important to least important, the several factors or considerations involved in the U.S. decision to drop the atomic bomb? Explain. 3. Today, the Japanese often say they have a "nuclear allergy," and the government accordingly has proclaimed "three nuclear principles," that it will not own or manufacture nuclear weapons and will not allow them to be brought into Japan. Introduction In August 1945 American aircraft dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing over 100,000 people and injuring many more. Japan soon sued for peace and World War II ended. Ever since President Harry S. Truman made the fateful decision to unleash atomic weapons on Japan, contemporaries and historians have debated the morality, necessity, and consequences of the choice. Truman said he authorized the use of the atomic bombs on populated areas because that was the only way to shorten the war and save American lives. Until the 1960s most historians accepted that conclusion. But recent scholarship, although not denying the argument that American lives would have been spared, has suggested that other considerations also influenced American leaders: relations with Soviet Russia, emotional revenge, momentum, and perhaps racism. Scholars today are also debating why several alternatives to military use of the bomb were not tried. In early May 1945, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson appointed an Interim Committee, with himself as chairman, to advise on atomic energy and the uranium bombs the Manhattan Engineering District project was about to produce. In the committee's meeting of May 31, 1945, the decision was made to keep the bomb project a secret from the Russians and to use the atomic bomb against Japan. On June 11, 1945, a group of atomic scientists in Chicago, headed by Jerome Franck, futilely petitioned Stimson for a noncombat demonstration of the bomb in order to improve the chances for postwar international control of atomic weapons. The recommendations of the Interim Committee and the Franck Committee are reprinted here. Report of the Interim Committee on Military Use of the Atomic Bomb, May 1945 (1) Secretary Stimson explained that the Interim Committee had been appointed by him, with the approval of the President, to make recommendations on temporary war-time controls, public announcement, legislation and post-war organization. . . . He expressed the hope that the [four] scientists would feel completely free to express their views on any phase of the subject. The Secretary explained that General Marshall shared responsibility with him for making recommendations to the President on this project with particular reference to its military aspects; therefore, it was considered highly desirable that General Marshall be present at this meeting to secure at first hand the views of the scientists. The Secretary expressed the view, a view shared by General Marshall, that this project should not be considered simply in terms of military weapons, but as a new relationship of man to the universe. This discovery might be compared to the discoveries of the Copernican theory and of the laws of gravity, but far more important than these in its effect on the lives of men. While the advances in the field to date had been fostered by the needs of war, it was important to realize that the implications of the project went far beyond the needs of the present war. It must be controlled if possible to make it an assurance of future peace rather than a menace to civilization. The Secretary suggested that he hoped to have the following questions discussed during the course of the meeting: Future military weapons Future international competition Future research Future controls Future developments, particularly non-military. At this point General Marshall discussed at some length the story of charges and counter-charges that have been typical of our relations with the Russians, pointing out that most of these allegations have proven unfounded. The seemingly uncooperative attitude of Russia in military matters stemmed from the necessity of maintaining security. He said that he had accepted this reason for their attitude in his dealings with the Russians and had acted accordingly. As to the post-war situation and in matters other than purely military, he felt that he was in no position to express a view. With regard to this field he was inclined to favor the building up of a combination among like minded powers, thereby forcing Russia to fall in line by the very force of this coalition. General Marshall was certain that we need have no fear that the Russians, if they had knowledge of our project, would disclose this information to the Japanese. He raised the question whether it might be desirable to invite two prominent Russian scientists to witness the test. Mr. Byrnes expressed a fear that if information were given to the Russians, even in general terms, Stalin would ask to be brought into the partnership. He felt this to be particularly likely in view of our commitments and pledges of cooperation with the British. In this connection Dr. Bush pointed out that even the British do not have any of our blue prints on plants. Mr. Byrnes expressed the view, which was generally agreed to by all present, that the most desirable program would be to push ahead as fast as possible in production and research to make certain that we stay ahead and at the same time make every effort to better our political relations with Russia. It was pointed out that one atomic bomb on an arsenal would not be much different from the effect caused by any Air Corps strike of present dimensions. However, Dr. Oppenheimer stated that the visual effect of an atomic bombing would be tremendous. It would be accompanied by a brilliant luminescence which would rise to a height of 10,000 to 20,000 feet. The neutron effect of the explosion would be dangerous to life for a radius of at least two-thirds of a mile. After much discussion concerning various types of targets and the effects to be produced, the Secretary expressed the conclusion, on which there was general agreement, that we could not give the Japanese any warning; that we could not concentrate on a civilian area; but that we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible. At the suggestion of Dr. Conant the Secretary agreed that the most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers' houses. There was some discussion of the desirability of attempting several strikes at the same time. Dr. Oppenheimer's judgment was that several strikes would be feasible. General Groves, however, expressed doubt about this proposal and pointed out the following objections: (1) We would lose the advantage of gaining additional knowledge concerning the weapon at each successive bombing; (2) such a program would require a rush job on the part of those assembling the bombs and might, therefore, be ineffective; (3) the effect would not be sufficiently distinct from our regular Air Force bombing program. Report of the Franck Committee on the Social and Political Implications of a Demonstration of the Atomic Bomb (For a Non-Combat Demonstration), June, 1945 (2) The way in which the nuclear weapons, now secretly developed in this country, will first be revealed to the world appears of great, perhaps fateful importance. One possible way--which may particularly appeal to those who consider the nuclear bombs primarily as a secret weapon developed to help win the present war--is to use it without warning on an appropriately selected object in Japan. It is doubtful whether the first available bombs, of comparatively low efficiency and small size, will be sufficient to break the will or ability of Japan to resist, especially given the fact that the major cities like Tôkyô, Nagoya, Osaka and Kôbe already will largely be reduced to ashes by the slower process of ordinary aerial bombing. Certain and perhaps important tactical results undoubtedly can be achieved, but we nevertheless think that the question of the use of the very first available atomic bombs in the Japanese war should be weighed very carefully, not only by military authority, but by the highest political leadership of this country. If we consider international agreement on total prevention of nuclear warfare as the paramount objective and believe that it can be achieved, this kind of introduction of atomic weapons to the world may easily destroy all our chances of success. Russia, and even allied countries which bear less mistrust of our ways and intentions, as well as neutral countries, will be deeply shocked. It will be very difficult to persuade the world that a nation which was capable of secretly preparing and suddenly releasing a weapon, as indiscriminate as the rocket bomb and a thousand times more destructive, is to be trusted in its proclaimed desire of having such weapons abolished by international agreement. We have large accumulations of poison gas, but do not use them, and recent polls have shown that public opinion in this country would disapprove of such a use even if it would accelerate the winning of the Far Eastern war. It is true, that some irrational element in mass psychology makes gas poisoning more revolting than blasting by explosives, even though gas warfare is in no way more "inhuman" than the war of bombs and bullets. Nevertheless, it is not at all certain that the American public opinion, if it could be enlightened as to the effect of atomic explosives, would support the first introduction by our own country of such an indiscriminate method of wholesale destruction of civilian life. Thus, from the "optimistic" point of view--looking forward to an international agreement on prevention of nuclear warfare--the military advantages and the saving of American lives, achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan, may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and wave of horror and repulsion, sweeping over the rest of the world, and perhaps dividing even the public opinion at home. From this point of view a demonstration of the new weapon may best be made before the eyes of representatives of all United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America would be able to say to the world, "You see what weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future and to join other nations in working out adequate supervision of the use of this nuclear weapon." This may sound fantastic, but then in nuclear weapons we have something entirely new in the order of magnitude of destructive power, and if we want to capitalize fully on the advantage which its possession gives us, we must use new and imaginative methods. After such a demonstration the weapon could be used against Japan if a sanction of the United Nations (and of the public opinion at home) could be obtained, perhaps after a preliminary ultimatum to Japan to surrender or at least to evacuate a certain region as an alternative to the total destruction of this target. It must be stressed that if one takes a pessimistic point of view and discounts the possibilities of an effective international control of nuclear weapons, then the advisability of an early use of nuclear bombs against Japan becomes even more doubtful--quite independently of any humanitarian considerations. If no international agreement is concluded immediately after the first demonstration, this will mean a flying start of an unlimited armaments race. If this race is inevitable, we have all reason to delay its beginning as long as possible in order to increase our head start still further. . . . The benefit to the nation, and the saving of American lives in the future, achieved by renouncing an early demonstration of nuclear bombs and letting the other nations come into the race only reluctantly, on the basis of guess work and without definite knowledge that the "thing does work," may far outweigh the advantages to be gained by the immediate use of the first and comparatively inefficient bombs in the war against Japan. At the least, pros and cons of this use must be carefully weighed by the supreme political and military leader ship of the country, and the decision should not be left to considerations, merely, of military tactics. One may point out that scientists themselves have initiated the development of this "secret weapon" and it is therefore strange that they should be reluctant to try it out on the enemy as soon as it is available. The answer to this question was given above--the compelling reason for creating this weapon with such speed was our fear that Germany had the technical skill necessary to develop such a weapon without any moral restraints regarding its use. Another argument which could be quoted in favor of using atomic bombs as soon as they are available is that so much taxpayers money has been invested in those projects that the Congress and the American public will require a return for their money. The above-mentioned attitude of the American public opinion in the question of the use of poison gas against Japan shows that one can expect, it to understand that a weapon can sometimes be made ready only for use in extreme emergency; and as soon as the potentialities of nuclear weapons will be revealed to the American people, one can be certain that it will support all attempts to make the use of such weapons impossible. (1) and (2) From Major Problems in American Foreign Policy by Thomas G. Paterson. Copyright c 1978 by D.C. Heath and Company. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. The Potsdam Declaration, July 26, 1945 (3) Proclamation Defining the Terms for the Japanese Surrender July 26, 1945 (1) WE--THE PRESIDENT of the United States, the President of the National Government of the Republic of China, and the Prime Minister of Great Britain, representing the hundreds of millions of our countrymen, have conferred and agree that Japan shall be given an opportunity to end this war. (2) The prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States, the British Empire and of China, many times reinforced by their armies and air fleets from the west, are poised to strike the final blows upon Japan. This military power is sustained and inspired by the determination of all the Allied Nations to prosecute the war against Japan until she ceases to resist. (3) The result of the futile and senseless German resistance to the might of the aroused free peoples of the world stands forth in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan. The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry, and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military power backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland. (4) The time has come for Japan to decide whether she will continue to be controlled by those self-willed militaristic advisers whose unintelligent calculations have brought the Empire of Japan to the threshold of annihilation, or whether she will follow the path of reason. (5) Following are our terms. We will not deviate from them. There are no alternatives. We shall brook no delay. (6) There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest, for we insist that a new order of peace, security and justice will be impossible until irresponsible militarism is driven from the world. (7) Until such a new order is established and until there is convincing proof that Japan's war-making power is destroyed, points in Japanese territory to be designated by the Allies shall be occupied to secure the achievement of the basic objectives we are here setting forth. (8) The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshû, Hokkaidô, Kyûshû, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine. (9) The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives. (10) We do not intend that the Japanese shall be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation, but stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners. The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established. (11) Japan shall be permitted to maintain such industries as will sustain her economy and permit the exaction of just reparations in kind, but not those which would enable her to rearm for war. To this end, access to, as distinguished from control of, raw materials shall be permitted. Eventual participation in world trade relations shall be permitted. (12) The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government. (13) We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction. (3) This and other documents such as the Japanese surrender offer and the Imperial rescripts can be found in the appendices of Robert J. C. Buton Japan's Decision to Surrender (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1954.) Search Ava Avalon Home Document Collections Ancient 4000bce - 399 Medieval 400 1399 15th Century 1400 1499 16th Century 1500 1599 17th Century 1600 1699 18th Century 1700 1799 19th Century 1800 1899 20th Century 1900 1999 The Yalta Conference See Also : Agreement Relating to Prisoners of War and Civilians Liberated by Forces Operating Under Soviet Command and Forces Operating Under United States of America Command; February 11, 1945 February, 1945 Washington, March 24 - The text of the agreements reached at the Crimea (Yalta) Conference between President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Generalissimo Stalin, as released by the State Department today, follows: PROTOCOL OF PROCEEDINGS OF CRIMEA CONFERENCE The Crimea Conference of the heads of the Governments of the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which took place from Feb. 4 to 11, came to the following conclusions: I. WORLD ORGANIZATION It was decided: 1. That a United Nations conference on the proposed world organization should be summoned for Wednesday, 25 April, 1945, and should be held in the United States of America. 2. The nations to be invited to this conference should be: (a) the United Nations as they existed on 8 Feb., 1945; and (b) Such of the Associated Nations as have declared war on the common enemy by 1 March, 1945. (For this purpose, by the term "Associated Nations" was meant the eight Associated Nations and Turkey.) When the conference on world organization is held, the 21st Century 2000 - delegates of the United Kingdom and United State of America will support a proposal to admit to original membership two Soviet Socialist Republics, i.e., the Ukraine and White Russia. 3. That the United States Government, on behalf of the three powers, should consult the Government of China and the French Provisional Government in regard to decisions taken at the present conference concerning the proposed world organization. 4. That the text of the invitation to be issued to all the nations which would take part in the United Nations conference should be as follows: "The Government of the United States of America, on behalf of itself and of the Governments of the United Kingdom, the Union of Soviet Socialistic Republics and the Republic of China and of the Provisional Government of the French Republic invite the Government of -------- to send representatives to a conference to be held on 25 April, 1945, or soon thereafter , at San Francisco, in the United States of America, to prepare a charter for a general international organization for the maintenance of international peace and security. "The above-named Governments suggest that the conference consider as affording a basis for such a Charter the proposals for the establishment of a general international organization which were made public last October as a result of the Dumbarton Oaks conference and which have now been supplemented by the following provisions for Section C of Chapter VI: C. Voting "1. Each member of the Security Council should have one vote. "2. Decisions of the Security Council on procedural matters should be made by an affirmative vote of seven members. "3. Decisions of the Security Council on all matters should be made by an affirmative vote of seven members, including the concurring votes of the permanent members; provided that, in decisions under Chapter VIII, Section A and under the second sentence of Paragraph 1 of Chapter VIII, Section C, a party to a dispute should abstain from voting.' "Further information as to arrangements will be transmitted subsequently. "In the event that the Government of -------- desires in advance of the conference to present views or comments concerning the proposals, the Government of the United States of America will be pleased to transmit such views and comments to the other participating Governments." Territorial trusteeship: It was agreed that the five nations which will have permanent seats on the Security Council should consult each other prior to the United Nations conference on the question of territorial trusteeship. The acceptance of this recommendation is subject to its being made clear that territorial trusteeship will only apply to (a) existing mandates of the League of Nations; (b) territories detached from the enemy as a result of the present war; (c) any other territory which might voluntarily be placed under trusteeship; and (d) no discussion of actual territories is contemplated at the forthcoming United Nations conference or in the preliminary consultations, and it will be a matter for subsequent agreement which territories within the above categories will be place under trusteeship. [Begin first section published Feb., 13, 1945.] II. DECLARATION OF LIBERATED EUROPE The following declaration has been approved: The Premier of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the President of the United States of America have consulted with each other in the common interests of the people of their countries and those of liberated Europe. They jointly declare their mutual agreement to concert during the temporary period of instability in liberated Europe the policies of their three Governments in assisting the peoples liberated from the domination of Nazi Germany and the peoples of the former Axis satellite states of Europe to solve by democratic means their pressing political and economic problems. The establishment of order in Europe and the rebuilding of national economic life must be achieved by processes which will enable the liberated peoples to destroy the last vestiges of nazism and fascism and to create democratic institutions of their own choice. This is a principle of the Atlantic Charter - the right of all people to choose the form of government under which they will live - the restoration of sovereign rights and self-government to those peoples who have been forcibly deprived to them by the aggressor nations. To foster the conditions in which the liberated people may exercise these rights, the three governments will jointly assist the people in any European liberated state or former Axis state in Europe where, in their judgment conditions require, (a) to establish conditions of internal peace; (b) to carry out emergency relief measures for the relief of distressed peoples; (c) to form interim governmental authorities broadly representative of all democratic elements in the population and pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections of Governments responsive to the will of the people; and (d) to facilitate where necessary the holding of such elections. The three Governments will consult the other United Nations and provisional authorities or other Governments in Europe when matters of direct interest to them are under consideration. When, in the opinion of the three Governments, conditions in any European liberated state or former Axis satellite in Europe make such action necessary, they will immediately consult together on the measure necessary to discharge the joint responsibilities set forth in this declaration. By this declaration we reaffirm our faith in the principles of the Atlantic Charter, our pledge in the Declaration by the United Nations and our determination to build in cooperation with other peace-loving nations world order, under law, dedicated to peace, security, freedom and general well-being of all mankind. In issuing this declaration, the three powers express the hope that the Provisional Government of the French Republic may be associated with them in the procedure suggested. [End first section published Feb., 13, 1945.] III. DISMEMBERMENT OF GERMANY It was agreed that Article 12 (a) of the Surrender terms for Germany should be amended to read as follows: "The United Kingdom, the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics shall possess supreme authority with respect to Germany. In the exercise of such authority they will take such steps, including the complete dismemberment of Germany as they deem requisite for future peace and security." The study of the procedure of the dismemberment of Germany was referred to a committee consisting of Mr. Anthony Eden, Mr. John Winant, and Mr. Fedor T. Gusev. This body would consider the desirability of associating with it a French representative. IV. ZONE OF OCCUPATION FOR THE FRENCH AND CONTROL COUNCIL FOR GERMANY. It was agreed that a zone in Germany, to be occupied by the French forces, should be allocated France. This zone would be formed out of the British and American zones and its extent would be settled by the British and Americans in consultation with the French Provisional Government. It was also agreed that the French Provisional Government should be invited to become a member of the Allied Control Council for Germany. V. REPARATION The following protocol has been approved: Protocol On the Talks Between the Heads of Three Governments at the Crimean Conference on the Question of the German Reparations in Kind 1. Germany must pay in kind for the losses caused by her to the Allied nations in the course of the war. Reparations are to be received in the first instance by those countries which have borne the main burden of the war, have suffered the heaviest losses and have organized victory over the enemy. 2. Reparation in kind is to be exacted from Germany in three following forms: (a) Removals within two years from the surrender of Germany or the cessation of organized resistance from the national wealth of Germany located on the territory of Germany herself as well as outside her territory (equipment, machine tools, ships, rolling stock, German investments abroad, shares of industrial, transport and other enterprises in Germany, etc.), these removals to be carried out chiefly for the purpose of destroying the war potential of Germany. (b) Annual deliveries of goods from current production for a period to be fixed. (c) Use of German labor. 3. For the working out on the above principles of a detailed plan for exaction of reparation from Germany an Allied reparation commission will be set up in Moscow. It will consist of three representatives - one from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, one from the United Kingdom and one from the United States of America. 4. With regard to the fixing of the total sum of the reparation as well as the distribution of it among the countries which suffered from the German aggression, the Soviet and American delegations agreed as follows: "The Moscow reparation commission should take in its initial studies as a basis for discussion the suggestion of the Soviet Government that the total sum of the reparation in accordance with the points (a) and (b) of the Paragraph 2 should be 22 billion dollars and that 50 per cent should go to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics." The British delegation was of the opinion that, pending consideration of the reparation question by the Moscow reparation commission, no figures of reparation should be mentioned. The above Soviet-American proposal has been passed to the Moscow reparation commission as one of the proposals to be considered by the commission. VI. MAJOR WAR CRIMINALS The conference agreed that the question of the major war criminals should be the subject of inquiry by the three Foreign Secretaries for report in due course after the close of the conference. [Begin second section published Feb. 13, 1945.] VII. POLAND The following declaration on Poland was agreed by the conference: "A new situation has been created in Poland as a result of her complete liberation by the Red Army. This calls for the establishment of a Polish Provisional Government which can be more broadly based than was possible before the recent liberation of the western part of Poland. The Provisional Government which is now functioning in Poland should therefore be reorganized on a broader democratic basis with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad. This new Government should then be called the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity. "M. Molotov, Mr. Harriman and Sir A. Clark Kerr are authorized as a commission to consult in the first instance in Moscow with members of the present Provisional Government and with other Polish democratic leaders from within Poland and from abroad, with a view to the reorganization of the present Government along the above lines. This Polish Provisional Government of National Unity shall be pledged to the holding of free and unfettered elections as soon as possible on the basis of universal suffrage and secret ballot. In these elections all democratic and anti-Nazi parties shall have the right to take part and to put forward candidates. "When a Polish Provisional of Government National Unity has been properly formed in conformity with the above, the Government of the U.S.S.R., which now maintains diplomatic relations with the present Provisional Government of Poland, and the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of the United States of America will establish diplomatic relations with the new Polish Provisional Government National Unity, and will exchange Ambassadors by whose reports the respective Governments will be kept informed about the situation in Poland. "The three heads of Government consider that the eastern frontier of Poland should follow the Curzon Line with digressions from it in some regions of five to eight kilometers in favor of Poland. They recognize that Poland must receive substantial accessions in territory in the north and west. They feel that the opinion of the new Polish Provisional Government of National Unity should be sought in due course of the extent of these accessions and that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should thereafter await the peace conference." VIII. YUGOSLAVIA It was agreed to recommend to Marshal Tito and to Dr. Ivan Subasitch: (a) That the Tito-Subasitch agreement should immediately be put into effect and a new government formed on the basis of the agreement. (b) That as soon as the new Government has been formed it should declare: (I) That the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation (AVNOJ) will be extended to include members of the last Yugoslav Skupstina who have not compromised themselves by collaboration with the enemy, thus forming a body to be known as a temporary Parliament and (II) That legislative acts passed by the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation (AVNOJ) will be subject to subsequent ratification by a Constituent Assembly; and that this statement should be published in the communiqué of the conference. IX. ITALO-YOGOSLAV FRONTIER - ITALO-AUSTRIAN FRONTIER Notes on these subjects were put in by the British delegation and the American and Soviet delegations agreed to consider them and give their views later. X. YUGOSLAV-BULGARIAN RELATIONS There was an exchange of views between the Foreign Secretaries on the question of the desirability of a Yugoslav-Bulgarian pact of alliance. The question at issue was whether a state still under an armistice regime could be allowed to enter into a treaty with another state. Mr. Eden suggested that the Bulgarian and Yugoslav Governments should be informed that this could not be approved. Mr. Stettinius suggested that the British and American Ambassadors should discuss the matter further with Mr. Molotov in Moscow. Mr. Molotov agreed with the proposal of Mr. Stettinius. XI. SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE The British delegation put in notes for the consideration of their colleagues on the following subjects: (a) The Control Commission in Bulgaria. (b) Greek claims upon Bulgaria, more particularly with reference to reparations. (c) Oil equipment in Rumania. XII. IRAN Mr. Eden, Mr. Stettinius and Mr. Molotov exchanged views on the situation in Iran. It was agreed that this matter should be pursued through the diplomatic channel. [Begin third section published Feb. 13, 1945.] XIII. MEETINGS OF THE THREE FOREIGN SECRETARIES The conference agreed that permanent machinery should be set up for consultation between the three Foreign Secretaries; they should meet as often as necessary, probably about every three or four months. These meetings will be held in rotation in the three capitals, the first meeting being held in London. [End third section published Feb. 13, 1945.] XIV. THE MONTREAUX CONVENTION AND THE STRAITS It was agreed that at the next meeting of the three Foreign Secretaries to be held in London, they should consider proposals which it was understood the Soviet Government would put forward in relation to the Montreaux Convention, and report to their Governments. The Turkish Government should be informed at the appropriate moment. The forgoing protocol was approved and signed by the three Foreign Secretaries at the Crimean Conference Feb. 11, 1945. E. R. Stettinius Jr. M. Molotov Anthony Eden AGREEMENT REGARDING JAPAN The leaders of the three great powers - the Soviet Union, the United States of America and Great Britain - have agreed that in two or three months after Germany has surrendered and the war in Europe is terminated, the Soviet Union shall enter into war against Japan on the side of the Allies on condition that: 1. The status quo in Outer Mongolia (the Mongolian People's Republic) shall be preserved. 2. The former rights of Russia violated by the treacherous attack of Japan in 1904 shall be restored, viz.: (a) The southern part of Sakhalin as well as the islands adjacent to it shall be returned to the Soviet Union; (b) The commercial port of Dairen shall be internationalized, the pre-eminent interests of the Soviet Union in this port being safeguarded, and the lease of Port Arthur as a naval base of the U.S.S.R. restored; (c) The Chinese-Eastern Railroad and the South Manchurian Railroad, which provide an outlet to Dairen, shall be jointly operated by the establishment of a joint SovietChinese company, it being understood that the pre-eminent interests of the Soviet Union shall be safeguarded and that China shall retain sovereignty in Manchuria; 3. The Kurile Islands shall be handed over to the Soviet Union. It is understood that the agreement concerning Outer Mongolia and the ports and railroads referred to above will require concurrence of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The President will take measures in order to maintain this concurrence on advice from Marshal Stalin. The heads of the three great powers have agreed that these claims of the Soviet Union shall be unquestionably fulfilled after Japan has been defeated. For its part, the Soviet Union expresses it readiness to conclude with the National Government of China a pact of friendship and alliance between the U.S.S.R. and China in order to render assistance to China with its armed forces for the purpose of liberating China from the Japanese yoke. Joseph Stalin Franklin D. Roosevelt Winston S. Churchill February 11, 1945. Source: A Decade of American Foriegn Policy : Basic Documents, 1941-49 Prepared at the request of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations By the Staff of the Committe and the Department of State. Washington, DC : Government Printing Office, 1950 World War II Page Avalon Home Document Collections Ancient 4000bce - 399 Medieval 400 1399 15th Century 1400 1499 © 2008 Lillian Goldman Law Library 127 Wall Street, New Haven, CT 06511. Avalon Statement of Purpose Contact Us Yale Law Library University Library Yale Law School Search Morris Search Orbis 16th Century 1500 1599 17th Century 1600 1699 18th Century 1700 1799 19th Century 1800 1899 20th Century 1900 1999 21st Century 2000 - World War II: Japanese Home Front--Ketsugo (April 1945) The Emperor and the Japanese military were determined to resist. Emperor Hirohito approced the strategy of Ketsugo (January 1945). This was part of the overall strategy of bleeding the Americans to force a negotiated peace. Ketsugo meant self defense, As a national defense policy it meant preparing civilans to fight an American invasion. Figure 1.--Here we see Japanese school girls being trained in self defense. Note the sharpened bamboo It was a refinement of poles. And Japanese Army officers are observing the Japan's Shosango victory demonstration. Beginning in the 1930s, the Japanese plan which envisioned military began play an increading role in the schools. defending the home islands to the last man. The plan was to prepare the Japanese people psychologically to fight the Americans and die defending their homeland. There was to be no surrender, even civilians were not to surrender. Some Japanese sources claim that Japan was defeated and ready to surrender. Such claims are starkly disproved by what happened to civilians on Okinawa. The military there actively prevented civilians from surrendering and incouraged civilians to kill themselves. Ketsugo went a step further. It involved training civilians to actively resist an American invasion. The plan included training children, boys as well as girls, to fight with improvised weapons. The military began implementing the strategy of Ketsugo (April 1945). Soldiers were assigned to schools to train even primary-level children in the use of weapons like bamboo spears. I am not sure how widespread this effort was and how intensive the training. I have noted Japanese adults describing such traing they received in schools. Japanese officials warned that the Americans would kill men who surrendered instantly and rape women. There was no evidence forthis belief other than this was how the Imperial Japanese Army behaved in well-publicized Chinese incidents. Not only were Japanese soldiers not to surrender, but neither would civilians. Others Japanese sources have reported their was no serious training in their schools. A peace faction led by Foreign Minister Togo complained that Ketsugo would destroy the nation. General Anami retorted. "Those who can not fulfill their resonsibilities to the Emperor should commit hari-kiri. " He was intent that the entire nation should resist the Americans to the death. School Drill Drill was a very common part of European and American education in the 129th and early-20th century. This primarily consisted of marching and learming marching moves. It waa adopted primarily because it taught discipline. It was mote common for boys than girls. Japan after the Meiji Resoration established a national educational systen for the first time and used European models for their new system. The physical educational (PE) program as designed by the new Ministry of Education (MoE) at first involved light gymnastics, but over time, drill and evebtually overt military training became part of the phyical education system. The first PE program designed by the MoE was light gymnastics (1878). The primary purpose of the PE program was to promote health. The Moe made PE a required subject and adopted military gymnastics (1886). The MoE reorganized the PE and adopted military drill (early 20th century). The MoE gradually turned to military personnel for PE instructors. During the Taisho era (1912-26) about 50 percent of school PE teachers were military personnel. Schools began assigning military officers secondary and teriiary schools to teach military drill. This included both marching and military exercises. The military began to see school PE as preparing students for subsequent military training. [Okuma] At the end of World War II this was extended to preparing children to participate in resisting an anticipated American invasion-Ketsugo. Approval The Emperor and the Japanese military were determined to resist. Emperor Hirohito approved the strategy of Ketsugo (January 20, 1945). Strategy This was part of the overall strategy of bleeding the Americans to force a negotiated peace. Ketsugo meant self defense, As a national defense policy it meant preparing civilans to fight an American invasion. It was a refinement of Japan's Shosango victory plan which envisioned defending the home islands to the last man. The plan was to prepare the Japanese people psychologically to fight the Americans and die defending their homeland. There was to be no surrender, even civilians were not to surrender. Denials Some Japanese sources claim that Japan was defeated and ready to surrender. This tends to comne from those who want to pasint Japan as a victim of World War II. Such claims are starkly disproved by what happened to civilians on Okinawa. The military there actively prevented civilians from surrendering and incouraged civilians to kill themselves. Civilian Role Ketsugo went a step further. It involved training civilians to actively resist an American invasion. The plan included training children, boys as well as girls, to fight with improvised weapons. The military began implementing the strategy of Ketsugo (April 1945). Soldiers were assigned to schools to train even primary-level children in the use of weapons like bamboo spears. Boys were trained to strap on satchel charges and chasrge a tank, roll under it and set off the charge. I am not sure how widespread this effort was and how intensive the training. I have noted Japanese adults describing such traing they received in schools. Not only were Japanese soldiers not to surrender, but neither would civilians. Others Japanese sources have reported their was no serious training in their schools. Propaganda Japanese officials warned that the Americans would kill men who surrendered instantly and rape women. There was no evidence forthis belief other than this was how the Imperial Japanese Army behaved in well-publicized Chinese incidents. Peace Faction A peace faction led by Foreign Minister Togo complained that Ketsugo would destroy the nation. General Anami retorted. "Those who can not fulfill their resonsibilities to the Emperor should commit hari-kiri." He was intent that the entire nation should resist the Americans to the death. OPERATION KETSU-GO The sooner the Americans come, the better...One hundred million die proudly. - Japanese slogan in the summer of 1945. Japan was finished as a warmaking nation, in spite of its four million men still under arms. But...Japan was not going to quit. Despite the fact that she was militarily finished, Japan's leaders were going to fight right on. To not lose "face" was more important than hundreds and hundreds of thousands of lives. And the people concurred, in silence, without protest. To continue was no longer a question of Japanese military thinking, it was an aspect of Japanese culture and psychology. - James Jones, WWII Background: While Japan no longer had a realistic prospect of winning the war, Japan's leaders believed they could make the cost of conquering Japan too high for the Allies to accept, leading to some sort of armistice rather than total defeat. The Japanese plan for defeating the invasion was called OPERATION KETSUGŌ (決号作戦, Ketsugō; "Operation Codename Decision"). The Japanese had secretly constructed an underground headquarters which could be used in the event of Allied invasion to shelter the Emperor and Imperial General staff, and began preparing for the American invasion. Japanese Homeland Defense Strategy The strategy for Ketsu-Go was outlined in an 8 April 1945 Army Directive. It stated that the Imperial Army would endeavor to crush the Americans while the invasion force was still at sea. They planned to deliver a decisive blow against the American naval force by initially destroying as many carriers as possible, utilizing the special attack forces of the Air Force and Navy. When the amphibious force approached within range of the homeland airbases, the entire air combat strength would be employed in continual night and day assaults against these ships. In conducting the air operations, the emphasis would be on the disruption of the American landing plans. The principal targets were to be the troop and equipment transports. Those American forces which succeeded in landing would be swiftly attacked by the Imperial Army in order to seek the decisive victory. The principal objective of the land operation was the destruction of the American landing force on the beach. Ketsu-Go operation was designed as an all-out joint defense effort to be conducted by the entire strengths of the Army, Navy and Air Force. The basic plan for the operation called for the Navy to defend the coasts by attacking the invasion fleets with its combined surface, submarine, and air forces. The Air General Army would cooperate closely with the Navy in locating the American transports and destroying them at sea. Should the invasion force succeed in making a landing, the Area Army concerned would assume command of all naval ground forces in its area and would exercise operational control of air forces in support of ground operations. If the battle at the beach showed no prospect of a successful ending, then the battle would inevitably shift to inland warfare; hence, interior resistance would be planned. Guard units and Civilian Defense Corps personnel, with elements of field forces acting as a nucleus, would be employed as interior resistance troops. Their mission would be to attrite the Americans through guerrilla warfare, espionage, deception, disturbance of supply areas, and blockading of supplies when enemy landing forces advanced inland. It is interesting to note that the Japanese normally exercised little inter-service coordination throughout the war. Now when the homeland was threatened, the Japanese finally stressed inter-service coordination and unity of command. Operational preparations for Ketsu-Go were conducted in three phases. The first phase, during which defensive preparations and troop unit organization was completed, continued through July 1945. The second phase began in August and was intended to continue through September, during which training was to be conducted and all defenses improved. The third phase would see the completion of troop training and deployment, as well as the construction of all defense positions, would be completed during October. [The second and third phases were never completed because of the end of the war. Thus, if implemented, X-Day would have occurred just as Japanese defense plans had been completed. By July, Japanese officers were assessing that the invasion would occur in October or November 1945 due to the summer typhoon season.] The intent of Ketsu-Go was to inflict tremendous casualties on the American forces, thereby undermining the American people's will to continue the fight for Japan's unconditional surrender. This intent is clear in a boastful comment made by an Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) army staff officer in July 1945: We will prepare 10,000 planes to meet the landing of the enemy. We will mobilize every aircraft possible, both training and "special attack" planes. We will smash one third of the enemy's war potential with this air force at sea. Another third will also be smashed at sea by our warships, human torpedoes and other special weapons. Furthermore, when the enemy actually lands, if we are ready to sacrifice a million men we will be able to inflict an equal number of casualties upon them. If the enemy loses a million men, then the public opinion in America will become inclined towards peace, and Japan will be able to gain peace with comparatively advantageous conditions. In the summer of 1945 Japanese strategists identified the will of the American people as the US strategic center of gravity and a critical vulnerability as the infliction of high casualties. Defense of Kyushu The Japanese were extremely accurate as to predicting the location of the American landing zones. The Sixteenth Area Army would be utilized as an assault group to be rushed to the area of the main American effort. Their mission would be to annihilate the American forces as soon after the initial landings as possible. The defensive plan called for a major counterattack to be delivered within two weeks of the initial American landings. As stated by a Japanese officer, the object of the defense was "to frustrate the enemy's landing plans with a counterattack like an electric shock, and at the proper moment to annihilate the enemy by close-range fire, by throwing hand grenades, and by hand-to-hand combat." The defense positions in Kyushu were built in accordance with the precepts laid down in The Three Basic Principles on How to Fight Americans, which had been developed as a result of lessons learned in south Pacific combat. In brief, these principles were: - Positions should be constructed beyond effective range of enemy naval bombardment. - Cave type positions should be constructed for protection against air raids and naval bombardment. - Inaccessible high ground should be selected as protection against flame throwing tanks. Air operations against American landings on Kyushu were to be the responsibility of the 5th Naval Air Fleet and 6th Air Army, both under the control of the Air General Army. Planes were to be released in waves of 300-400, at the rate of one wave per hour, against the invasion fleet. Sufficient fuel had been stored for this use, but only about 8,000 pilots were available. Although the pilots were poorly trained and no match against experienced American pilots, they were capable enough to carry out suicide attacks against ships. At the end of the war, Japan had approximately 12,725 planes. The Army had 5,651 and the Navy had 7,074 aircraft of all types. While many of these were not considered combat planes, almost all were converted into kamikaze planes. The Japanese were planning to train enough pilots to use all of the aircraft that were capable of flying. Naval operations against the invasion fleet would be conducted in two phases. The first phase would consist of attriting the American fleet as it approached the home islands. The remaining 38 Japanese fleet submarines would attempt to attrite as many transports as possible. They were to serve as launch platforms for manned suicide torpedoes called "Kaitens". Although the Kaitens had not proved too successful in operations on the open ocean, the Japanese hoped that they would be effective in the restricted waters around the home islands. The five-man midget submarines, known as "Koryu," would also be employed with either two torpedoes or an explosive charge for use in a suicide role. The Navy planned to have 540 Koryu in service by the time of the invasion. A more advanced midget submarine, the "Kairyu," was a two man craft armed with either two torpedoes or an explosive charge. Approximately 740 Kairyu were planned by the fall of 1945. As the invasion fleet reached the landing areas, the second phase would commence. The 19 surviving Japanese destroyers would attempt to attack the American transports at the invasion beaches. Suicide attack boats, called "Shinyo," carrying 550 pounds of explosives in their bows, would strike from hiding places along the shore. Closer to shore, there would be three rows of divers, or “Fukuryu” arrayed so that they were about 60 feet apart. Underwater lairs for the Fukuryu were to be made of reinforced concrete with steel doors. As many as 18 divers could be stationed in each underwater "foxhole." Clad in a diving suit and breathing from oxygen tanks, a Fukuryu carried an explosive charge, which was mounted on a stick with a contact fuse. He was to swim up to landing craft and detonate the charge. The Navy had hoped for 4,000 men to be trained and equipped for this suicide force by October. Ground operations against the American landings called for the ground forces to quickly determine the area of the invasion and concentrate in this area as many troops as possible before the invasion began. Medium and heavy artillery were to cover the landing craft approaches, the beaches, and plains areas surrounding the beaches. Commanders were told to be ready to swiftly divert the necessary troops and military supplies to other sectors at any time. The ground forces were to be concentrated in planned operational areas. Movement of ground forces would be primarily at night by foot, and the movement of war supplies would be by rail or water as the situation permitted. Troop movements were to be executed even under American air attacks. Coastal and Inland Defenses / Fortifications The Japanese had extensive experience with how the Americans conducted amphibious assaults in the Pacific. In late 1944, the Japanese also sent a team of officers to debrief the Germans on their defenses at Normandy and how the Allies assaulted to gain a foothold in Europe. From these experiences the Japanese coastal defenses on Kyushu were divided into three zones. 1. Beach Positions - These positions were to be used mainly in beach fighting and for firing against landing craft. They were to be heavily fortified and concealed for protection against naval gunfire. Coastal fortifications were constructed in cave type shelters to withstand intense bombings and bombardments, especially from naval gunfire. They were to have the ability to conduct close range actions and withstand attacks from flamethrowers, explosives, and gas. Their purpose was to defeat any landing attempt. 2. Foreground Zone - If the beach positions could not prevent a landing, then the attack was to be delayed in this zone with localized counterattacks and raids. Obstacles, hidden positions, timed land mines, and assault tunnels utilizing natural terrain features were prepared to slow the attack and to fight within the enemy lines to limit the effectiveness of naval gunfire and close air support. 3. Main Zone of Resistance - This zone was the area where the main resistance was to be established. Battalions and larger units would occupy key terrain positions which were independent of each other. These installations were constructed as underground fortresses capable of coping with close range actions in which flame-throwers, explosives, and gas would be used. This resistance zone was intended to stop the American advance and set up the major counterattack that was to decisively defeat the attack. The Japanese paid special attention to camouflage of their positions even during construction. Defensive positions were to be concealed from air, land, and sea observation. Within all three zones, dummy positions were constructed for deception. Cave installations were to be heavily reinforced and capable of withstanding a direct hit by naval gunfire. Pillboxes, assault positions, sniper positions, and obstacles were to be organized for close quarter combat and mutually supporting. Each position was to store water, ammunition, fuel, antitank weapons, food, salt, vitamin pills, and medical supplies. Inland fortifications were also constructed to provide cover and concealment for heavy equipment such as tanks, motor vehicles and artillery as well as bomb proof storage of ammunition and fuel. As on many islands throughout the Pacific, these storage shelters were impervious to American air and naval bombardment. The defensive plan called for the use of the Civilian Volunteer Corps, a mobilization not of volunteers but of all boys and men 15 to 60 and all girls and women 17 to 40, except for those exempted as unfit. They were trained with hand grenades, swords, sickles, knives, fire hooks, and bamboo spears. These civilians, led by regular forces, were to make extensive use of night infiltration patrols armed with light weapons and demolitions. Also, the Japanese had not prepared, and did not intend to prepare, any plan for the evacuation of civilians or for the declaration of open cities. The southern third of Kyushu had a population of 2,400,000 within the 3,500 square miles included in the Prefectures of Kagoshima and Miyazaki. The defensive plan was to actively defend the few selected beach areas at the beach, and then to mass reserves for an all-out counterattack if the invasion forces succeeded in winning a beachhead. The Japanese were determined to fight the final and decisive battle on Kyushu. At whatever the cost, Japanese military leaders were planning to repel any U.S. landing attempt. The defense of the Japanese home islands centered on two primary operations: the Army's fanatical defense of the beaches, and the employment of Kamikaze planes and suicide boats against transports. The Japanese plans for suicide attacks were much more extensive than anything the U.S. had yet experienced in the war. The Japanese special suicide forces were seen as a "Divine Wind" which was to save their nation just as the "Divine Wind" had driven the Mongol hordes back in the thirteenth century. Citation: "OPERATION KETSU-GO." Federation of American Scientists. Web. 09 Dec. 2010. <http://www.fas.org/irp/eprint/arens/chap4.htm>. BY BILL DIETRICH Seattle Times staff reporter Historians are still divided over whether it was necessary to drop the atomic bomb on Japan to end World War II. Here is a summary of arguments on both sides: Why the bomb was needed or justified: The Japanese had demonstrated near-fanatical resistance, fighting to almost the last man on Pacific islands, committing mass suicide on Saipan and unleashing kamikaze attacks at Okinawa. Fire bombing had killed 100,000 in Tokyo with no discernible political effect. Only the atomic bomb could jolt Japan's leadership to surrender. With only two bombs ready (and a third on the way by late August 1945) it was too risky to "waste" one in a demonstration over an unpopulated area. An invasion of Japan would have caused casualties on both sides that could easily have exceeded the toll at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The two targeted cities would have been firebombed anyway. Immediate use of the bomb convinced the world of its horror and prevented future use when nuclear stockpiles were far larger. The bomb's use impressed the Soviet Union and halted the war quickly enough that the USSR did not demand joint occupation of Japan. Why the bomb was not needed, or unjustified: Japan was ready to call it quits anyway. More than 60 of its cities had been destroyed by conventional bombing, the home islands were being blockaded by the American Navy, and the Soviet Union entered the war by attacking Japanese troops in Manchuria. American refusal to modify its "unconditional surrender" demand to allow the Japanese to keep their emperor needlessly prolonged Japan's resistance. A demonstration explosion over Tokyo harbor would have convinced Japan's leaders to quit without killing many people. Even if Hiroshima was necessary, the U.S. did not give enough time for word to filter out of its devastation before bombing Nagasaki. The bomb was used partly to justify the $2 billion spent on its development. The two cities were of limited military value. Civilians outnumbered troops in Hiroshima five or six to one. Japanese lives were sacrificed simply for power politics between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Conventional firebombing would have caused as much significant damage without making the U.S. the first nation to use nuclear weapons. [Trinity stories | Deeper into things | Interactive activities | Internet links | Seattle Times | Up a level] Copyright, 1995, Seattle Times Company