* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CT issues in PET / CT scanning

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

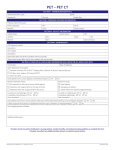

abc CT issues in PET / CT scanning ImPACT technology update no. 4 David Platten ImPACT October 2004 Introduction Since its introduction in the 1970s, X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanning has become a widespread three-dimensional (3D) imaging modality, capable of producing anatomical images with sub-millimetre resolution. Positron emission tomography (PET) also produces 3D images, but these reflect physiological function, showing the uptake of injected positron-emitting radiopharmaceuticals within the body. The recent introduction of hybrid PET / CT scanners combines the two modalities, enabling both anatomical and functional images to be collected in a single session. PET / CT scanning is generally provided as a nuclear medicine service, where there may not be experience in X-ray CT. This leaflet outlines some of the issues related to CT that should be considered when using a PET / CT scanner. PET / CT scanners Current PET / CT systems consist of a single, long-bore gantry with the PET and CT systems adjacent to one another (Figure 1). In some systems a single housing is placed over the two gantries, in others the gantries have separate covers, but are positioned very close to one-another. The CT scanner component of the systems tend to be existing models that are available as separate systems, with the same image quality and radiation dose characteristics. The patient usually undergoes the CT part of the examination first (Figure 1a), and then the couch is moved further into the gantry to perform the PET scan (Figure 1b). Figure 1: An example PET / CT system (a) (b) CT PET CT issues in PET / CT scanning 1 www.impactscan.org PET / CT image registration PET images contain few anatomical Figure 2: Software registration [14] landmarks, and are often reviewed in conjunction with a set of CT images to aid in locating areas of tracer uptake. In the past PET and CT images had to be collected on separate scanners, with the patient having to move from one scanner to the other, possibly on different days. Workstations have been available for some time that overlay the PET and CT images onto one another. These attempt to register the images using anatomical markers to account for differences in set-up position between the two scans (Figure 2). This technique works best for areas of the body that are immobile, such as the brain. Organs in other anatomical regions such as the abdomen are mobile, with scope for them to change position between the two scans. This makes the image registration process more difficult, and possibly less accurate. The accuracy of software registration can be improved with the use of reference markers, attached to the surface of the patient. The markers must be made of a material that is visible on the images from both modalities. The advent of hybrid PET / CT systems has simplified image registration – the PET and CT data sets are collected sequentially, on the same system, without the need for the patient to move to another scanner. This removes the image registration problems introduced by different patient set-up positions. Once the CT scan is complete, the patient couch is moved further into the gantry to commence the PET scan. The two data sets can be considered to be inherently registered; just the distance between the PET and CT positions needs to be taken into account. Another registration issue that must be considered is the flex of the patient couch. A normal CT couch is shown in Figure 3. As the couch is moved into the gantry, more of the patient’s weight is taken by the part of the couch that is unsupported by the base. This results in a flex of the couch as it is moved into the gantry. For accurate image registration it is important that the degree of couch flex does not change as the patient is moved from the CT to PET acquisition positions. This would cause registration problems in PET / CT, because when the patient is moved from the CT to the PET acquisition positions the couch flex will increase, resulting in a lower patient position for the PET scan compared with the CT part. This difference in vertical position will vary depending on the weight of the patient. CT issues in PET / CT scanning 2 www.impactscan.org Figure 3: A normal CT patient couch scan plane Base Special couch designs can be used to reduce this flexing problem. Figure 4 shows a re-designed couch for use in PET / CT, where the couch is fixed to a moving pedestal. The whole pedestal / couch assembly moves into and out of the gantry. When a patient lays on the couch it will flex a certain amount, but the degree of flex remains constant regardless of how far the couch is moved into the gantry. This ensures that the vertical position of the patient is the same for the CT and PET acquisitions. Figure 4: A re-designed CT couch for PET / CT Registration accuracy Part of the assessment of a PET / CT system should include testing of the accuracy of image registration between the PET and CT image data sets. A test object is required Figure 5: Schematic diagram of a that contains a known 3D distribution of PET / CT registration phantom objects, visible in both the CT and PET image data sets. The two sets of phantom images can then be registered using the system software, and the resulting fused image checked for accuracy. Figure 5 shows an example of a PET / CT image registration phantom. The grey box contains two 68Ge / 68Ga line sources which are visible to both PET and CT. The source needles are orientated such that the image registration can be checked in all three dimensions. CT issues in PET / CT scanning 3 www.impactscan.org CT attenuation correction of PET images The absorption and scatter of 511 keV PET photons in the patient’s tissue leads to a reduced count-rate at the detectors. This results in areas of the PET image showing activity levels that are below the true value. Attenuation maps of the patient can be used to correct for this effect. Stand-alone PET systems usually achieve this using radioactive line sources which measure the attenuation through the patient volume [11]. The acquisition of this data requires many minutes, and considerably adds to the total PET examination time. The standard deviation of values within these attenuation maps tends to be high, which can impact upon the accuracy of the corrected PET images. CT numbertissue = µtissue − µwater × 1000 µwater Equation 1: CT number In a PET / CT system, the CT images can be used to generate attenuation correction maps to apply to PET images. CT image pixel values are given in Hounsfield Units (HU), which are proportional to the attenuation coefficient (µ) of the tissue being represented (Equation 1). Compared with maps acquired from radioactive line sources, CT image maps are quicker to obtain and have very low noise, reducing the total scan time by up to 30 – 40 % [13] and the likelihood of patient movement. However, some issues specific to CT must be considered. Energy dependence of attenuation maps Figure 6: Mapping CT number to PET attenuation coefficient 0.18 0.16 0.14 µ PET (cm ) 0.12 -1 CT data is gathered using X-rays with peak energy of around 120 keV, and an effective mean energy of the order of 70 keV. Attenuation coefficients are energy dependent, so attenuation maps derived from CT need to be adjusted before they can be applied to 511 keV PET images. Several methods have been suggested to achieve this [1, 2]. One such method is to provide a conversion from CT number to PET attenuation using a bi-linear scale, as shown in Figure 6. 0.1 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.02 0 -1000 -500 0 500 1000 1500 CT number (HU) CT image artefacts In general, image artefacts can be defined as any area where there are systematic discrepancies between an object and the image of that object. Artefacts can be thought of as structured image noise. The presence of artefacts in a CT image data set will result in errors in the generated attenuation map. In turn, applying this incorrect attenuation map to the PET images will result in an apparent increase or decrease in activity levels in some areas of the images. It is important, therefore, to ensure that CT artefacts are minimised when they are used for attenuation maps. CT issues in PET / CT scanning 4 www.impactscan.org In addition, PET images are often used for quantification, such as calculating standard uptake values (SUVs). These calculations rely on the images being a true representation of radiopharmaceutical distribution within the patient. Any image artefacts will introduce errors into the calculated values. CT images are subject to many types of image artefact, some of which are discussed below. Metal artefacts Some materials cannot be correctly represented in a CT image due to their high attenuation coefficients, including metal items such as dental fillings and joint replacements. The corresponding Hounsfield Units of these materials are off the CT number scale of many scanners, which can lead to streaking artefacts through the images. These streaks will cause errors in any attenuation map that is derived for use in a corresponding PET data set [3]. Some CT scanners feature metal artefact reduction algorithms that attempt to minimise these effects. A visual comparison of attenuation-corrected against non-attenuation-corrected PET images will help to identify artefacts [4]. Photon starvation Streak artefacts in CT images can be due to photon starvation. This occurs when insufficient X-ray photons pass through wide parts of the patient, leading to noisy projections. When the projections are reconstructed the noise is magnified, resulting in streaks. This is a particular problem for areas such as the shoulders and hips. Some scanners use adaptive filtration of the projections to reduce this effect. Where areas of a projection have low signal they are smoothed, reducing the noise. An extension of this is multi-dimensional adaptive filtration, where further steps are taken to reduce noise levels in certain projections [5]. Patient movement Patient movement during CT scanning results in image artefact, which appear as streaks or shaded discontinuities across an image. Voluntary motion, such as the movement of the chest during inspiration and expiration, and involuntary movements from the heart and peristalsis, can cause these artefacts. A CT scan is usually short enough for patients to hold their breath, removing the possibility of breathing artefact. However, PET scans require minutes to acquire, and so are carried out with the patient shallow breathing. The resulting PET image data contains some chest motion blurring. This is in contrast to the much more rapidly acquired CT data, where the chest wall is imaged at full inspiration. Using a breathhold CT scan with a breathing PET scan can cause mis-registration of hot-spots near the abdomen / chest boundary. This effect can be minimised by allowing the patient to shallow breathe during the CT scan [6], or by scanning with a normal expiration breath-hold [7]. CT issues in PET / CT scanning 5 www.impactscan.org CT contrast agents Iodine-based CT contrast agents can cause attenuation mismatches [8, 9]. At CT energies, they have a high contrast with the surrounding tissue, but at 511 keV, the attenuation coefficient of iodine is similar to that of water. This can lead to apparent elevated areas of activity in the attenuation corrected PET images. In most cases the artefacts can be identified by careful observation of the CT and PET images. Radiation dose In most PET / CT scanning situations the CT part of the scan does not need to be of diagnostic quality, as the CT images are just being used to generate attenuation correction maps. Where this is the case there is a lower CT image quality requirement, enabling the use of lower CT exposure factors, with a corresponding drop in patient radiation dose. It is common for the CT scanner to be run at reduced tube currents, about half the normal diagnostic exposure, of around 70–80 mA. However, there is potential for artefacts to be introduced as a result, such as the photon starvation effects mentioned earlier. Patient radiation doses from CT scans depend on the scan protocol and the anatomical region being scanned. Using diagnostic exposure factors, effective doses for head scans are generally in the range 1 to 3 mSv. Abdominal scans have a wider range, 5 to 20 mSv, depending on the extent of the scan and selected exposure factors. If the CT scanner is run at a lower mA, in the 70–80 mA range, the magnitude of these doses will half. Radiation dose to the patient from the PET component of the scan is around 10 mSv. For whole-body PET / CT scanning, the CT scan constitutes a significant additional radiation dose. ImPACT’s CT Dosimetry spreadsheet is widely used to estimate the radiation doses to patients from CT. It is available free of charge from our website, www.impactscan.org/ctdosimetry.htm [10]. The spreadsheet requires the National Radiological Protection Board’s SR250 Monte Carlo dataset to run [12]. Summary PET / CT is now well-established clinically, with hundreds of systems installed worldwide. The use of CT data for attenuation correction of PET images reduces the total examination time when compared with a stand-alone PET scanner by as much as 30 – 40 %. However, careful consideration must be given to the CT scan protocols used in order to minimise the effect of artefacts on the PET images. Co-registration of CT and PET images on a PET / CT scanner is a simple process when compared to using anatomical or fiducial markers with separately acquired scans. The fused images allow functional abnormalities to be accurately located within the patient anatomy. Where image artefacts are likely, e.g. where implants are present, care should be taken to correctly interpret the attenuation-corrected PET images. CT issues in PET / CT scanning 6 www.impactscan.org The additional radiation dose burden to the patient as a result of the CT scan should be considered. Optimisation of CT scan parameters is necessary to minimise patient radiation dose, but care must be taken to avoid the introduction of additional image artefacts. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Visvikis D, Costa DC, Croasdale I et al. CT-based attenuation correction in the calculation of semi-quantitative indices of [18F]FDG uptake in PET. Eur J Nucl Med 2003; 30: 344-53. Burger C, Goerres G, Schoenes S et al. PET attenuation coefficients from CT images: experimental evaluation of the transformation of CT into PET 511-keV attenuation coefficients. Eur J Nucl Med 2002; 29: 922-7. Kamel EM, Burger C, Buck A et al. Impact of metallic dental implants on CTbased attenuation correction in a combined PET/CT scanner. Eur Radiol 2003; 13: 724-8. Goerres GW, Ziegler SI, Burger C et al. Artifacts at PET and PET / CT caused by metallic hip prosthetic material. Radiology 2003; 226: 557-84. Kachelriess M, Watzke O, Kalender WA. Generalized multi-dimensional adaptive filtering for conventional and spiral single-slice, multi-slice, and cone-beam CT. Med Phys 2001; 28(4): 475-90. Beyer T, Antoch G, Müller S et al. Acquisition protocol considerations for combined PET/CT imaging. J Nucl Med 2004; 45 (1 suppl): 25S-35S. Goerres GW, Burger C, Kamel E et al. Respiration-induced attenuation artifact at PET / CT: technical considerations. Radiology 2003; 226: 906-10. Antoch G, Kuehl H, Kanja J et al. Dual-modality PET / CT scanning with negative oral contrast agent to avoid artifacts: introduction and evaluation’, Radiology 2004; 230: 879-85. Dizendorf E, Hany TF, Buck A et al. Cause and magnitude of the error induced by oral CT contrast agent in CT-based attenuation correction of PET emission studies. J Nucl Med 2003; 44 (5): 732-8. ImPACT CT patient dosimetry calculator, www.impactscan.org/ctdosimetry.htm Ostertag H, Kubler WK, Doll J et al. Measured attenuation correction methods. Eur J Nucl Med 1989; 15(11):722-6. www.nrpb.org/publications/software/sr250.htm Townsend DW, Carney JPJ, Yap JT et al. PET/CT today and tomorrow. J Nucl Med 2004; 45 (1 suppl): 4S-14S. Image courtesy of Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf, www.uke.uni-hamburg.de/imi CT issues in PET / CT scanning 7 www.impactscan.org Bibliography Valk PE, Bailey DL, Townsend DW, Maisey MN. Positron emission tomography. Basic science and clinical practice. Springer 2003. Vogel WV, Oyen WJG, Barentsz JO et al. PET/CT: panacea, redundancy, or something in between? J Nucl Med 2004; 45 (1 suppl): 15S-24S. Bockisch A, Beyer T, Antoch G et al. Positron emission tomography / computed tomography – imaging protocols, artifacts, and pitfalls. Mol Imaging Biol 2004; 6 (4): 188-99. von Schulthess GK, ‘Positron emission tomography versus positron emission tomography / computed tomography: from “unclear” to “new-clear” medicine. Mol Imaging Biol 2004; 6 (4): 183-7. UK PET Special Interest Group, www-pet.umds.ac.uk/UKPET (sic) ImPACT, St George’s Hospital, Blackshaw Road, London SW17 0QT T: 020 8725 3366 F: 020 8725 3969 E: [email protected] W: www.impactscan.org ImPACT is the UK’s national CT scanner evaluation centre, providing publications, information and advice on all aspects of CT scanning. Funded by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), it is part of a comprehensive medical imaging device evaluation programme. © Crown copyright 2004 CT issues in PET / CT scanning 8 www.impactscan.org