* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Healthy Coping in Diabetes

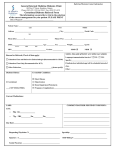

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript