* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Origin of Alternation of Generations

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

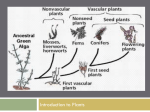

Origin of Alternation of Generations Alternation of generations is a common component of all land plants, vascular and nonvascular; it does not express itself in the same manner in any other organisms. Given the other overwhelming similarities in land plant biochemistry, photosynthetic pigments and tissue organization, it seems that the easiest assumption is that they are derivatives of a common ancestor. The origin of alternation of generations is, however, unclear. Considerable evidence suggests that the land plants (both vascular and non-vascular) originated from a green algal ancestor that was haploid for most of its lifecycle, and only after gametic fusion and fertilization was it briefly diploid. The resulting zygote was the only diploid part of the life cycle, and it was immediately followed by meiosis. Thus, the zygote directly gave rise to spores and the haploid generation was re-established. The gap from four derivatives to more than four has already been bridged in some algal species by an intercalated mitotic division. But the spore producing structure remains that of the former egg in a unicellular organ. It could hardly be termed a sporangium, although it still had the same function. Was this early form simply a retained zygote, undergoing a chance mitotic division? If it continued in its developmental program to become a spore there was no problem, but what if it did not? If it were not to become a spore, what developmental program would be initiated? What selection of developmental programs would be latent within these plants? Two opposing theories for this phenomenon have been proposed. Unfortunately for students of plant morphology, both theories are supported by data in the fossil record. It is far from clear though to explain how both cases could have occurred during the origin of a common lineage of land plants. Transformation (homologous) theory. Simply stated, the transformation theory makes the assumption that the mass of cells forming mitotically from the zygote may simply adopt the developmental plan of the gametophyte, thereby forming a diploid sporophyte appearing identical to the haploid gametophyte. Evidence for this very simple theory for the origin of alternation of generations abounds among the algae, where there are examples of the Chlorophyta, Phaeophyta and Rhodophyta that express isomorphic alternation of generations-all of which apparently arose independently during the course of evolution. In land plants, the bryophyte Anthoceros, the hornwort, has a sporophyte generation that is photosynthetic and therefore largely independent of the gametophyte generation on which it develops. Like a gametophyte, it displays an extended lifespan. Among vascular land plants, in Psilotum, which is possibly the most primitive extant vascular land plant, the gametophyte is stem-like, persistent and independent in growth, and similar to the sporophyte may produce tracheids within its thickest axes. In fact, it has been suggested that stem emergences seen on the base of the rhyniophyte Aglaophyton (formerly Rhynia gwynne-vaughnii) are examples of primitive archegonia. The figure to the right indicates a reconstruction of such a body. This concept first engendered great excitement among paleobotanists, since no sporangia had been seen on the aerial axes of this plant. It was even theorized that Rhynia major was the sporophyte of this plant. However, since that time, sporangia have been identified on axes of Aglaophyton. Therefore, although some specimens might have been gametophytes, there is no compelling evidence that this must have been the case. Also, there are no compelling examples of antheridia or embryos. Interpolation (also called antithetic or heterologous) theory. The antithetic theory maintains that the sporophyte and gametophyte generations are fundamentally dissimilar and that the first mitotically dividing zygotes (embryos) entered into a substantially unique developmental pattern, not copying the established developmental events of the gametophytes. This theory suggests that the embryos were in a unique developmental relationship with the gametophyte and therefore entered into an equally unique generation, eventuating in the production of spores. Thus, the sporophyte generation was an innovation of critical significance. A sequence that is likely to have initiated this process is occurrence of a cycle or two of mitosis preceding the meiotic division of the brief diploid generation. Presumably, there was not even a sporangium to start with, since all of the cells derived from the zygote underwent meiosis. From this rudimentary condition, more spores, and ultimately a multicellular sporophyte could be produced. Further retention of the sporophyte over the course of time could eventually result in the formation of vegetative tissues to support the energetically expensive process of producing numerous spores and organs with more complex forms of dissemination. Once some of these land plants possessed the ability to produce and effectively disseminate numerous spores, the development of a complex sporophyte presented considerable evolutionary advantages in competing for the production of more haploid offspring. Evolutionary pressure favoring the production of more spores, more protective organs and the development sophisticated organs for spore production and dissemination (sporangia) would An illustration of the antithetic theory according to Bower. (A) Sporophyte consisting principally of a sporangium producing spores (like Anthoceros does today) (B) Branching of sporangium (C) Increased robustness of sporophyte (D) Independent Rhynia like sporophyte. be expected and this would presumably occur swiftly as the early (pre-?)vascular plants diversified to occupy the land environment. Bowers envisioned the sequence of events as shown to the right. Which model seems the best supported by currently available data? There is clearly data supporting the origin of alternation of generations through both homologous and heterologous origins. Certainly, there are strong examples of each in different groups. However, vascular land plants appear to have originated through a heterologous method according to current data. The rhyniophytes display such remarkable diversity that it is not difficult to imagine them as an ancestral group to both the tracheophytes and bryophytes. The evidence of "archegonia" in Aglaophyton is not entirely compelling because of the lack of embryos and antheridia. At the current time, the interpolation theory seems more logically compelling as an explanation for the origin of alternation of generations in land plants. Why did sporophytes become dominant in vascular plants? For genetic reasons, it seems likely that the diploid generation, with its greater resistance to the occurrence of lethal recessive genes, which are expressed directly in haploids, would be favored. Diploids are capable of masking such recessives, as long as the organism has only one copy of such a gene. And as the complexity of the plants increased, the benefit of masking lethal recessives became even more valuable. On the other hand, bryophytes appear to have diverged from this strategy, adopting a cryptic life cycle and occupying environments that were occupied by vascular plants only later in their evolution. The bryophytes appear to have adopted a reverse strategy, although in many ways retaining much the same internal and external morphology.