* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Individualizing Therapy For Patients With Neovascular AMD And DME

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

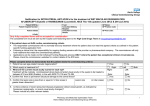

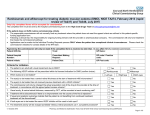

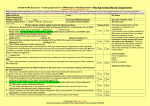

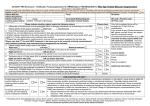

CME MONOGRAPH Instant CME Certificate Available With Online Testing and Course Evaluation Individualizing Therapy for Patients With Neovascular AMD and DME: Considerations for Short- and Long-Term Management Proceedings from an Experts Roundtable Discussion Allen C. Ho, MD (Chair and Moderator) Robert L. Avery, MD David M. Brown, MD Jason S. Slakter, MD Original Release Date: April 1, 2014 Most Recent Review Date: April 1, 2014 Expiration Date: April 30, 2015 Jointly sponsored by The University of Louisville Department of Continuing Education and MedEdicus This continuing education activity is supported through an unrestricted educational grant from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Distributed with PURPOSE AND TARGET AUDIENCE Experience of anti-VEGF treatment now well under way for neovascular agerelated macular degeneration (AMD) and attentions are directed at better understanding how to individualize therapy for achieving long-term results. Treatment of diabetic macular edema (DME) is undergoing a paradigm shift as anti-VEGF therapy is becoming the treatment standard. Patients with either of these diseases require lifelong treatment. Results from new research is adding to the available evidence in helping inform management approaches for short-term and for long-term treatment. This educational activity is designed for retina specialists and other physicians treating AMD and DME. DESIGNATION STATEMENT The University of Louisville Continuing Medical Education & Professional Development designates this educational activity for a maximum of 2.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their paticipation in the activity. ACCREDITATION This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the University of Louisville and MedEdicus LLC. The University of Louisville School of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. INSTRUCTIONS & REGISTRATION The course takes approximately 2 hours. Please read the monograph, consult any additional references if needed. Once the materials have been reviewed, you will go to http://bit.ly/neovascular14 to take a post test followed by course evaluations, after which you will be able to generate your CME certificate. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Upon completing this educational activity, participants should be able to: • Describe results of recent studies evaluating anti-VEGF therapy in patients with AMD and DME • Apply information on therapeutic strategies to manage persistent fluid in patients with neovascular AMD and DME who are receiving anti-VEGF therapy • Select appropriate anti-VEGF and other therapeutic strategies for long-term management of patients with neovascular AMD and DME HARDWARE & SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS High speed Internet connection (Broadband, Cable or DSL) Windows 2000 or higher 256 MBs or more of RAM Internet Explorer 6.0 higher Windows Media Player 10.0 or higher Adobe Acrobat 7.0 or higher Course content compatible with Mac OS DISCLOSURE As a sponsor accredited by the ACCME, the University of Louisville School of Medicine must ensure balance, independence, objectivity, and scientific rigor in all its sponsored educational activities. All faculty participating in this CME activity were asked to disclose the following: 1. Names of proprietary entities producing health care goods or services—with the exemption of nonprofit or government organizations and non–healthrelated companies—with which they or their spouse/partner have, or have had, a relevant financial relationship within the past 12 months. For this purpose, we consider the relevant financial relationships of a spouse/partner of which they are aware to be their financial relationships. 2. Describe what they or their spouse/partner received (eg, salary, honorarium). 3. Describe their role. 4. No relevant financial relationships. 2 DISCLOSURES CME Reviewers: Shlomit Schaal, MD, PhD, has no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests. John Sorenson, MD, has no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests. Faculty: Dr Robert L. Avery: Alcon, Inc (Consultant, Speaker); Allergan, Inc (Consultant, Investigator); Bausch + Lomb Incorporated (Consultant); Genentech, Inc (Consultant, Speaker, Investigator); Iridex Corporation (Consultant); Notal Vision (Consultant); Novartis (Consultant, Ownership Interest); Ophthotech Corporation (Consultant, Ownership Interest); QLT Inc (Consultant); Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Consultant, Ownership Interest); Replenish Inc (Consultant, Advisory Board, Ownership Interest, Intellectual Property Rights, Royalty); and SKS Ocular, LLC (Ownership Interest). Dr David M. Brown: Allergan, Inc (Consultant, Independent Contractor); Genentech/Roche (Consultant, Independent Contractor); Novartis (Consultant, Independent Contractor); and Regeneron/Bayer (Consultant, Independent Contractor). Dr Allen C. Ho: Allergan, Inc (Consultant, Scientific Advisory Board); Genentech, Inc (Consultant, Scientific Advisory Board); and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Consultant, Scientific Advisory Board). Dr Jason S. Slakter: Acucela Inc (Consultant, Contracted Research); Alimera Sciences (Contracted Research); Bayer (Contracted Research); Genentech, Inc (Contracted Research); Genzyme Corporation (Contracted Research); Lpath Incorporated (Consultant, Contracted Research); Novagali Pharma SAS (Contracted Research); OHR Pharmaceutical Inc (Consultant, Contracted Research); Oraya Therapeutics, Inc (Consultant, Contracted Research); Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Consultant, Contracted Research); sanofiaventis U.S. LLC (Contracted Research); Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Contracted Research); and SKS Ocular, LLC (Ownership Interest). MedEdicus: Cynthia Tornallyay, RD, MBA, CCMEP, and Barbara Lyon have no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests. Writer: Tony Realini, MD, MPH: Alcon, Inc (Consultant, Contracted Research); Lumenis Ltd (Honoraria, Contracted Research); and Sensimed AG (Contracted Research). University of Louisville CME & PD: The CME & PD staff and Advisory Board have nothing to disclose with the exception of Dr Douglas Coldwell: Sirtex, Inc (Speaker) and DFine, Inc (Consultant). Medium or Combination of Media Used: Online Enduring Material Activity Method of Physician Participation: Printed and Online/Digital Monograph Estimated Time to Complete the Educational Activity: 2.0 hours COMMERCIAL SUPPORT This activity is supported through an unrestricted educational grant from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. SPECIAL SERVICES If you need special accommodations due to a disability or for an alternative form of course materials, please contact us at [email protected]. Continuing Medical Education & Professional Development fully complies with the legal requirements of the ADA and the rules and regulations thereof. PROVIDER CONTACT INFORMATION For questions about the CME activity content, please contact University of Louisville at [email protected]. PRIVACY POLICY All information provided by course participants is confidential and will not be shared with any other parties for any reason without permission. COPYRIGHT © 2014 MedEdicus LLC FACULTY Allen C. Ho, MD (Chair and Moderator) Professor of Ophthalmology Thomas Jefferson University School of Medicine Attending Surgeon Wills Eye Retina Service Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Robert L. Avery, MD Founder California Retina Consultants and Research Foundation Santa Barbara, California David M. Brown, MD Retina Consultants of Houston Clinical Associate Professor Weill Cornell Medical College, Methodist Hospital Houston, Texas Jason S. Slakter, MD Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology New York University School of Medicine Partner Vitreous Retina Macula Consultants of New York INTRODUCTION The clinical management of retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic macular edema (DME) continues to evolve rapidly as novel therapies and new clinical trial outcomes expand and refine our practice patterns. In this educational activity, our primary goal is to clarify optimal management of these common retinal diseases in the context of existing and emerging data from new and ongoing clinical trials. We also will explore the therapeutic landscape and provide pearls for selecting the appropriate therapy for each patient on an individualized basis, as well as examine the long-term management of these chronic diseases. We hope that the discussion that took place among our expert faculty panel provides insight for the management of patients in your clinical practice. —Allen C. Ho, MD, Chair and Moderator NEOVASCULAR AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION Dr Ho: First-line therapy for neovascular AMD using inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor ( VEGF) is a paradigm shift that is now supported by a substantial volume of Level I evidence. Equally importantly, we now have highquality data from randomized clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of not just 1 or 2, but multiple anti-VEGF agents. The ability of retina specialists to improve significantly the quality of life of the legions of older adults with neovascular AMD has never been greater. These trials are, importantly, not all industry sponsored, and many have been designed to directly compare these agents, head to head. Driven by this compelling body of evidence, we now have a high treatment burden because many patients need frequent monitoring and retreatment. It is neither practical nor necessary for all patients to be seen and retreated monthly. However, once we deviate from the frequent treatment schedule that has been shown in many trials to provide the best visual acuity ( VA) outcomes, we find ourselves with less data to support alternative treatment regimens. 3 Dr Avery: CATT was a 2-year noninferiority study comparing bevacizumab and ranibizumab for the management of neovascular AMD. There were 4 treatment groups, with each drug being dosed either monthly or PRN, with prespecified PRN retreatment criteria that indicated active neovascularization and included fluid visualized with optical coherence tomography (OCT), new or persistent hemorrhage, decreased VA from the previous visit, or dye leakage or increase in lesion size on fluorescein angiogram (FA). The primary outcome measure was the mean change in VA at 1 year. Both 1-year1 and 2-year2 results have been reported in the literature. These results demonstrated that the 2 drugs were fairly similar in efficacy, particularly when dosed monthly throughout the 24-month study (Figure 1). The mean change in VA at 1 year in the monthly bevacizumab group (8.0 Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] letters) was statistically noninferior to that shown in the monthly ranibizumab group (8.5 ETDRS letters). In the PRN groups, gains in the ranibizumab and bevacizumab groups were 6.5 and 5.9 letters, respectively, also noninferior. After the first year, patients in the monthly treatment groups were rerandomized to either continue monthly treatment or to switch to PRN treatment using the same retreatment criteria. At 2 years, the mean gains in VA in the monthly ranibizumab and bevacizumab groups were 8.8 and 7.8 letters, respectively, while the corresponding PRN groups gained 6.7 and 5.0 letters, respectively, which were also noninferior with respect to drug comparison, but the monthly outcomes were better than the PRN outcomes (P=.046). Secondary outcomes also were evaluated. Patients in the bevacizumab PRN group required more frequent injections than those in the ranibizumab PRN group (14.1 vs 12.6 over 24 months, respectively; P=.01). Likewise, 45.5% of patients in the monthly ranibizumab group were fluid-free on OCT at 24 months compared with only 4 Mean Change in Visual Acuity Score From Baseline (no. of letters) Herein we plan to shed some light on current practice patterns in an evidence-based manner, and to provide some clinical pearls for the management of patients with AMD in your practices. These practice patterns are informed by the lessons we have learned, and continue to learn, from recent and ongoing clinical trials, including the CATT (Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials), HARBOR (Study of Ranibizumab Administered Monthly or an on As-Needed Basis in Patients With Subfoveal Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration), and VIEW ( VEGF Trap-Eye Investigation of Efficacy and Safety in Wet AMD) trials, among others around the world, such as IVAN (Inhibit VEGF in Age-related Choroidal Neovascularization), MANTA (Multicenter Anti-VEGF Trial in Austria), and GEFAL (French Evaluation Group Avastin Versus Lucentis). Dr Avery, please provide an overview of the CATT study. 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Mean no. Inj: R-M: 22 B-M: 23 R-PRN: 12.6 B-PRN: 14.1 Ranibizumab Monthly Bevacizumab Monthly Ranibizumab as Needed Bevacizumab as Needed +8.8 +7.8 +6.7 +5.0 Ranibizumab difference: 8.8-6.7=2.1 letters Bevacizumab difference: 7.8-5.0=2.8 letters 0 4 12 N (146, 135, 287, 270) 24 36 52 64 (145, 135, 285, 270) 76 88 104 (134, 129, 264, 251) Follow-Up Weeks Figure 1. CATT results at 2 years.2 13.9% of those in the bevacizumab PRN group (P=.0003). Also, mean retinal thickness was significantly lower at 24 months in the 2 monthly treatment groups compared with their respective PRN treatment groups. The clinical importance of the reduced retinal thickness is unclear. In general, thinner is better; however, there is concern that in some patients, the retina can be too thin, which can be associated with decreased vision—for instance, if there is geographic atrophy. Dr Ho: What is your practical take-home message from CATT regarding drug efficacy? Dr Avery: The take-home message is that these 2 drugs and these 2 treatment regimens were fairly equivalent. When given monthly, there was no significant difference in visual outcome between bevacizumab and ranibizumab, despite improved anatomic outcomes with ranibizumab. There was a slight sacrifice of VA by using PRN instead of monthly treatment. Also, there was a slight and statistically significant increase in systemic serious adverse events with bevacizumab vs ranibizumab. A similar trend has been observed in 3 other studies at the 1-year time point—IVAN,3 GEFAL4 and MANTA5—but not in LUCAS (Lucentis Compared to Avastin Study).6 The clinical significance of an approximately 30% higher rate of systemic serious adverse events with bevacizumab is not known. Dr Ho: Panelists, are there any additional take-home messages from CATT? Dr Slakter: I have always had the clinical impression that ranibizumab produced a better clinical outcome in some selected patients. When dosed monthly, the drugs are equivalent; however, with PRN dosing there is less of an anatomic effect with bevacizumab than with ranibizumab. As Dr Avery noted, the proportion of patients without fluid on OCT was significantly greater in the ranibizumab PRN group than in the bevacizumab PRN group. Therefore, when given the choice, I prefer to use ranibizumab over bevacizumab. The CATT data certainly demonstrate that I have not been choosing the wrong agent. Interestingly, given that both drugs were similar in efficacy when dosed monthly, physicians who prefer bevacizumab also use the CATT data to support their practice patterns. CATT did demonstrate that bevacizumab dosed PRN may not be the best choice. Dr Avery: I completely agree that CATT was taken as a positive outcome for proponents of both bevacizumab and ranibizumab. The difference in the number of injections is also important and worth repeating. The PRN bevacizumab group needed more injections per year than the PRN ranibizumab group, and despite these extra injections, there was a trend for VA outcomes in the bevacizumab PRN group to be not quite as good as those in the ranibizumab PRN group (5.0 vs 6.7 letters gained at 2 years). Dr Ho: In CATT, the PRN groups received a single initial injection, then were followed monthly for disease activity; this protocol is different from many other studies with less-than-monthly treatment arms in which there were 3 initial monthly injections, or a “loading dose”. Be aware of this nuance when considering CATT in comparison to IVAN, MANTA, and GEFAL. Efficacy is always a high consideration in choosing a treatment agent and regimen, but safety considerations are typically primary. How do the ocular and systemic safety data from CATT affect your choice of antiVEGF agents? Dr Brown: In terms of systemic safety, it is difficult to make recommendations from the CATT data, as the actual numbers of patients with systemic adverse events was very small in each of the groups. First, I have difficulty believing that any of these drugs, when injected in small quantities into the vitreous cavity, achieve adequate systemic levels to cause systemic adverse events. Such events—myocardial infarctions and strokes, for example—happen naturally in people who are in the age range of our AMD patients, and whether the events seen in these trials were causally attributable to the drugs has not been established. Second, the ocular safety issues are more interesting, and among these, the risk for endophthalmitis is one that concerns me. In CATT, the doses of bevacizumab were prepared under a strict protocol and provided in glass vials. This is significantly different from the standard formulation of bevacizumab I use in the clinic, in which the drug is formulated in small batches under a variable degree of scrutiny and is supplied in a plastic syringe in a plastic bag. In plastic syringes, proteins aggregate,7 and the amount of active drug available is variable. I was much more comfortable using the strictly formulated bevacizumab in CATT than I am using the formulation available in clinical practice. I am unconvinced that the results of CATT can be generalized to our routine clinical experience in terms of the true risk for endophthalmitis due to drug formulation. Dr Avery: I believe that there is a systemic effect of these intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents. We have conducted pharmacokinetic studies demonstrating that all 3 of the major agents produce a transient but sometimes fairly pronounced drop in the free VEGF levels as measured in plasma.8 This drop in free VEGF levels is very transient with ranibizumab, which has a very short systemic half-life, but it is prolonged with bevacizumab and with aflibercept, lasting at least 7 days and sometimes up to a month after the injection. I agree with Dr Brown regarding causality. Whether this systemic VEGF inhibition correlates with the systemic adverse events or not is still unclear. But the pharmacokinetic data support a biologic plausibility that some of these adverse events could be caused by the systemic VEGF level changes. Dr Ho: Many share some of the concerns regarding systemic safety, although we recognize that all these AMD trials are underpowered for the purpose of discerning statistically meaningful differences in safety events. The body of evidence from all 4 comparative clinical trials (CATT, IVAN, MANTA, GEFAL) shows a potential disadvantage to bevacizumab with respect to systemic adverse events supported by biologic plausibility. Furthermore, any compounded preparation, by definition, is prepared with less stringent safety conditions than a commercially manufactured product. On the other hand, likely every retina specialist around the world has used intravitreal bevacizumab to the benefit of his or her patients with great clinical and overall value. Bevacizumab is used widely because it is significantly less expensive than ranibizumab, or aflibercept, and when dosed comparably, bevacizumab and ranbizumab produce comparable VA outcomes. However, there may be some other costs to consider. In addition to potential systemic adverse effects just mentioned, these include the additional potential risk for contamination from a compounded preparation of bevacizumab for intraocular use, and also the potential liability of using an off-label drug when 2 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs formulated specifically for intraocular use are available. We are fortunate to have treatment options. Let us consider the newest anti-VEGF agent approved for the treatment of neovascular AMD, aflibercept. Dr Slakter, please summarize the VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 trials. Dr Slakter: The VIEW studies were aflibercept’s registry trials, of which the FDA requires 2. Patients with neovascular AMD were randomized to 1 of 4 treatment groups: aflibercept 2 mg dosed monthly; aflibercept 2 mg dosed in 3 monthly loading doses, and then every other month; aflibercept 0.5 mg monthly; or ranibizumab 0.5 mg monthly. Aflibercept 5 The primary outcome was the proportion of patients losing fewer than 15 ETDRS letters at the 52-week time point, using a noninferiority statistical analysis of the aflibercept groups in comparison to ranibizumab. Both 1-year9 and 2-year10 outcomes have been reported. At 1 year, the proportions of patients losing fewer than 15 letters in both aflibercept 2-mg groups were statistically noninferior to those in the ranibizumab group in both VIEW studies, with approximately 94% to 96% of patients in all groups meeting this end point in both studies. In the second year of the VIEW studies, all treatment groups transitioned to a capped PRN dosing strategy that mirrored traditional PRN therapy, with the exception that patients were treated every 3 months even if retreatment criteria were still not met. At 2 years, the mean change in VA from baseline was 7.6 ETDRS letters in the aflibercept 2-mgevery-other-month group and 7.9 ETDRS letters in the ranibizumab monthly group (Figure 2), a difference that was not statistically significant. These similar outcomes were accomplished with fewer injections in the aflibercept group (average 11.2 injections over 2 years) compared with the ranibizumab group (average 16.5 injections over 2 years). The key take-home message from the VIEW studies is that with aflibercept, every-other-month dosing after 3 monthly loading doses provides stability of VA comparable to ranibizumab dosed every month. It is important, however, to acknowledge that we do not typically treat our ranibizumab patients every month. Most of us use a treat-and-extend approach. The VIEW data do not specifically tell us that aflibercept works longer than ranibizumab. A patient who can extend to 8 weeks using ranibizumab will not likely extend to 16 weeks using aflibercept. But these data do suggest that aflibercept may be more durable in some patients, although not necessarily in every patient. Dr Ho: The capped PRN treatment regimen in year 2 of the VIEW trials mandated injections every 3 months and may have undermined injection number differences in the VIEW trials; that is, there was a requirement to inject when clinical circumstances may not have called for an injection. Naturally, that applies for both ranibizumab and aflibercept. Is there anything else to add to this excellent summary of the VIEW trials for aflibercept? 6 14 12 ETDRS Letters 2 mg was eventually approved by the FDA, so I will not talk further about the 0.5-mg treatment arm: I will focus on the 2-mg groups dosed either monthly or every other month following 3 monthly loading doses. 10 7.9 7.6 7.6 6.6 8 9.3 8.7 8.4 8.3 6 4 2q4 Rq4 2q8 0.5q4 Rq4 2q8 2q4 0.5q4 2 0 0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 52 56 60 64 68 72 76 80 84 88 92 96 Week Rq4 2q4 0.5q4 2q8 Rq4=ranibizumab every 4 weeks 2q4=aflibercept 2 mg every 4 weeks 0.5q4=aflibercept 0.5 mg every 4 weeks 2q8=aflibercept 2 mg every 8 weeks after 3 monthly loading doses Figure 2. VIEW 2-year outcomes. Mean change in VA.10 Dr Brown: Dr Slakter correctly points out that VIEW does not support that aflibercept lasts longer than ranibizumab for the average patient. In VIEW, there was no arm in which ranibizumab was dosed every 2 months. It is the general consensus that for many patients aflibercept lasts approximately a week or so longer than ranibizumab in a treat-and-extend regimen. In my experience, when dosing ranibizumab on a treat-and-extend regimen, I typically can extend 1 to 2 weeks beyond the standard 4-week dosing regimen for most patients. Being able to dose every 8 weeks vs every 6 weeks means fewer injections and fewer visits to my office per year. Dr Avery: The second year of the VIEW studies utilized a capped PRN arm. Everyone got injected at the 3-month mark whether they needed it or not. Even with this regimen, there was a slight difference between the ranibizumab and the aflibercept PRN groups of approximately a half injection less per year with aflibercept. This is further indirect evidence that aflibercept has a little longer durability of effect than does ranibizumab. My clinical impression is similar to that of Dr Brown, that we get a slightly longer durability of effect— perhaps a week longer on average—with aflibercept than with ranibizumab. Dr Ho: The study design of the VIEW studies—specifically the capped PRN approach in year 2—limits our knowledge of the true duration of action of aflibercept and of ranibizumab. Might these patients have gone longer than 3 months if they had not been required to receive a PRN treatment at month 3? Dr Ho: That is an excellent point and it is clear that these clinical trials answer specific questions, but provide only guidelines for therapy. Individualized therapy is an important concept for clinicians to practice because neovascular AMD is a heterogeneous condition with a broad range of injection requirements to control exudative disease. Dr Brown, please summarize the HARBOR trial and provide us the key takehome points from that study. Dr Brown: HARBOR was a 12-month prospective randomized study in treatment-naïve patients with subfoveal neovascular AMD assigned to treatment with ranibizumab using 1 of 4 different treatment regimens: 0.5 mg or 2 mg, each dosed either monthly or PRN after 3 monthly loading doses. PRN retreatment criteria were prespecified and pertained to reductions in VA or evidence of active neovascularization by spectral-domain (SD) OCT. The primary end point was the mean change in best corrected VA from baseline at month 12. The 12-month results have been reported.11 To summarize the results, there was no benefit to the increased dose of ranibizumab (Figure 3). The mean VA gains were 10.1, 8.2, 9.2, and 8.6 ETDRS letters in the 0.5-mg monthly, 0.5-mg PRN, 2-mg monthly, and 2-mg PRN groups, respectively, at 12 months (Table 1). Key secondary end points also were evaluated. The proportions of patients gaining 15+ ETDRS letters ranged from 30% to 36% across the groups, and mean changes in central foveal thickness by SD-OCT ranged from 161 to 172 microns. In the PRN groups, the 0.5-mg group required 7.7 injections on average, compared with 6.9 injections in the 2-mg group. The key take-home message from HARBOR is that the 0.5-mg dose of ranibizumab appears to be at the top of the dose-response curve, with no benefit from a higher dose in treatment-naïve patients. Mean #Rx as needed Yr 1 & 2 0.5 mg: 7.7 & 5.6 2.0 mg: 6.9 & 4.3 12 Mean Change in BCVA (letters) Dr Avery: This discussion very elegantly illustrates the need to practice individualized medicine. Consider the HARBOR trial. In the PRN arms of that study, there were a few patients—approximately 6% or 7%—who required monthly injections over 2 years. But there were also patients who needed only 6, or 5, or 4, or even 3 injections over the same time period. The need for retreatment is highly individual, and it is difficult to predict up front who will need more and who will need fewer injections. 10 8 6 0.5 mg monthly 0.5 mg as needed 2.0 mg monthly 2.0 mg as needed 4 2 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Evaluation Interval (Month) Figure 3. Two-year VA outcomes in the HARBOR study evaluating multiple doses of ranibizumab for AMD.11 Dr Ho: The HARBOR Study had a strict and low tolerance for retreatment and is our only major neovascular AMD trial to use all SD-OCT imaging. Many retina specialists thought that the 2-mg dose of ranibizumab would achieve higher efficacy, but this result was not realized. Are there any other lessons to be learned from HARBOR? Table 1. Mean change in BCVA (letters) in the Harbor Study11 Ranibizumab 0.5 mg monthly 0.5 mg PRN 2.0 mg monthly 2.0 mg PRN Month 12 Month 24 Change Month 12 to Month 24 +10.1 +8.2 +9.2 +8.6 +9.1 +7.9 +8.0 +7.6 —1.0 —0.3 —0.3 —1.0 Dr Avery: The 2-mg dose appeared to have a slightly longer half-life, as evidenced by the fewer number of injections required by participants in the 2-mg PRN group compared with those in the 0.5-mg PRN group. So the higher dose provided a little more durability of effect. Dr Brown: The safety profiles were similar in both dosing groups as well. There was not an increase in adverse events when the dose was increased 4-fold. This finding is reassuring in light of the uncertainty surrounding the systemic adverse event issues seen in the large clinical trials. I am not very concerned about systemic adverse events rates in AMD patients with our current dose of ranibizumab. 7 Dr Ho: We have now discussed the key data for each of our anti-VEGF agents. Let us set the premise for just this next question. If cost and insurance coverage were not issues, what would be your first choice for therapy for a typical newly diagnosed neovascular patient with AMD? Dr Slakter: I would choose aflibercept for 2 reasons. First is its apparent increased durability. In a chronic disease with the potential need for lifelong therapy, an extra week or 2 between injections significantly reduces the overall number of injections necessary, and thus reduces the cumulative probability of developing a complication related to the injection procedure, such as endophthalmitis. Second is that aflibercept seems to be effective in eyes that have suboptimal responses to ranibizumab or bevacizumab, such as those with retinal pigment epithelial detachments,12 polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy,13 or, in my personal experience, central serous chorioretinopathy. I want to select the drug most likely to give the best response from day 1. On the basis of the data and my personal experience to date, that drug would be aflibercept. Dr Brown: My first choice would be ranibizumab or aflibercept. I would start with ranibizumab, and if the macula is not dry after the first 3 injections, I would switch to aflibercept. I recognize that ranibizumab may have the shortest half-life of the available agents,8 but it is also familiar and well established in clinical practice. Genentech also has a more fully developed access program and sample ranibizumab that allows me to treat patients who need it on the spot without having to wait for insurance authorization. Dr Avery: I, too,would start with ranibizumab or aflibercept, given that cost would not be an issue. In a patient with any issues that make me concerned about the risk for systemic safety events—the extremely elderly, those with a past stroke, or cardiovascular disease or diabetes, for instance—I will usually err on the side of ranibizumab. In the absence of potential safety issues, I often will start with aflibercept because it seems to have a longer duration of effect. Dr Ho: My own practice pattern is in consensus with those of my fellow panel members. Now that we have discussed the agents, let us discuss the various dosing regimens. Our typical choices are monthly—or every other month with aflibercept—vs PRN vs treat-and-extend. Once you have selected a drug, be it aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab, what is your preferred treatment regimen for wet AMD? 8 Dr Avery: My preferred approach is treat-and-extend. I give an initial injection and reevaluate in 4 weeks. If a patient’s macula is flat and dry on OCT at 4 weeks, I will extend by 2 weeks at a time. I do not routinely give 3 monthly loading doses before extending. In CATT, patients essentially got 12 monthly loading doses in the first year before going to PRN in year 2, and the outcomes were not substantially different from those in the group who received PRN therapy from the start. So it is not clear to me that 3 monthly loading doses are necessary. Exceptions include high-risk patients, such as those blind in the fellow eye, in whom I tend to stay on monthly therapy. If we achieve stability and the disease involutes, I may transition to PRN therapy. Dr Brown: I start with 3 monthly loading doses of my first-choice anti-VEGF drug. We have evidence that a 3-monthly-loading-dose regimen results in better VA than does 1 dose.14,15 Then I reassess. If the macula is dry, I extend. With ranibizumab, I will not extend past 10 weeks, according to the pharmacokinetic data. For aflibercept, I do not yet know the maximum time. There are a few patients— perhaps 15% or 20%—who will not require any further injections after the 3 loading doses. However, most will start leaking again at 6 or 7 weeks post-injection. The CATT data showed us that the patients in the PRN arms progressively had loss of their initial VA gains. In light of these data, in my opinion, PRN therapy for neovascular AMD should be abandoned for standard care. Why would you insist on recurrence of exudation before redosing an efficacious medication? Dr Slakter: I use the treat-and-extend regimen following a 3-dose load. I use the initial response during those 3 months to inform my extension. If the macula is dry at 1 month vs 2 or 3 months, I am more confident about extending. I typically will not extend beyond 10 to 12 weeks. I use those 3 injections to give me an idea of how quickly I can extend. If the macula is flat very quickly, then I feel more comfortable extending more rapidly. If the patient still has some fluid after 3 injections, then I will continue monthly until the macula is dry, and extend very slowly. Dr Ho: I also use the treat-and-extend approach, but I am mindful that the literature supports that nothing provides better VA outcomes than monthly or frequent therapy; consider the decline in vision in the CATT trial in year 2 when monthly subjects were changed to a PRN regimen. For this reason, I have a very low threshold for retreating, and if I am undecided, I typically will retreat. My treat-andextend injection interval limit for ranibizumab or aflibercept is typically 12 weeks, but not all patients require chronic ongoing therapy and therefore, with involuted lesions, I may treat PRN. Let us now discuss those difficult patients we all have in our practices who have suboptimal responses to our initial anti-VEGF intervention. What do we consider a suboptimal response, and how do we handle these patients? Dr Slakter: If after 3 monthly injections there is absolutely no change in the retina, I will switch to a different agent. If I get a partial response, I will continue through a total of 4 to 5 injections. Before switching, however, I seek to determine whether the agent is not working, or whether it simply is not lasting long enough. One approach in these patients is to bring them in 2 weeks after their injection, rather than 4 weeks later, and see if their macula is dry. Some patients respond well, but the effect wears off before 4 weeks. If the macula is dry at 2 weeks but not at 4 weeks, I will use an every-2-week treatment regimen. If they are not dry 2 weeks after an injection, it is time to try something different. Dr Brown: In my patients who require retreatment more often than every 4 weeks, I also consider the presence of lesion characteristics that might help guide my choice of therapy. If I see evidence of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, the EVEREST study supports photodynamic therapy in combination with anti-VEGF therapy,16 for instance. The same is true for presumed AMD that is actually undiagnosed central serous chorioretinopathy, which occurs in patients who are poor responders to anti-VEGF therapy—this can be treated with photodynamic therapy alone without anti-VEGF therapy. Likewise, an extrafoveal lesion may best be treated with photocoagulation as in the Macular Photocoagulation Study (MPS)17 rather than with anti-VEGF therapy. Dr Ho: If you have determined the need to switch to another therapy, to what do you switch? Dr Avery: I typically progress from bevacizumab to ranibizumab to aflibercept, in that order, except for the high-risk patients I mentioned earlier in whom I start with ranibizumab. If I cannot get the disease under control with very frequent injections, photodynamic therapy is often my next step. Dr Ho: Related to the nonresponder patient is the patient who was responding but has now stopped responding. Consider a patient who responded very well to your therapy and has a completely dry macula, but which then begins leaking again. What is your next step for such a patient? Dr Avery: Issues such as tolerance and tachyphylaxis have been debated recently, but in most instances I think these are simply cases of the disease getting worse. In these situations, I either dose the drug more frequently or switch to a different drug. Fortunately, these sorts of relapses are uncommon. Typically, patients who are well controlled on therapy remain well controlled, and often can get by with less for long periods of time. Dr Ho: Does changing to a different agent produce better results in these patients? Dr Brown: Interestingly, in the few studies that have evaluated therapy changes, there are typically small improvements in structure but not commensurate changes in function.18,19 What I mean is that the OCT looks better, but the vision does not improve. One important issue is that of selection bias: we change therapy only in the patients who had a poor response to initial therapy. These may be the patients who will do poorly on any therapy. Nevertheless, they are in our practices and we have to do something. Switching therapy is reasonable, but may not be very effective in most patients. Dr Ho: In the patients who remain dry and stable with good vision on therapy, is there an end to treatment or should they receive therapy indefinitely? Dr Avery: It is a challenge to know how to manage the patient who has successfully extended to 12 weeks for a long period of time. Should we stop abruptly, or wean by treating every 3 months or PRN for a year first? There are risks to continuing treatment as well as risks to withdrawing treatment. I have the risk-benefit talk with these patients and we make the decision together. In the 1-eyed patient, I am much more inclined to treat indefinitely. The risk of extending too long or of discontinuing therapy is that the patient will return with a subretinal hemorrhage in his or her only eye and never regain vision. I have 1-eyed patients whom I have treated monthly for up to 8 years who still have good vision. Dr Brown: Once we extend to 10 weeks, I obtain an FA, and in the absence of evidence of active neovascularization, I give the patient the option of reducing therapy. Dr Slakter: I start managing the expectations surrounding chronic therapy very early in the disease process. I inform patients that we are going to start with monthly therapy, and that they likely will need therapy for the rest of their lives, but my goal is to get them stable so we can see each other only every 3 months. If I can extend them to 3 months, I will treat them quarterly forever or at least until we have new forms of therapy. 9 Dr Ho: Is there a clinical pearl for the management of available if prespecified criteria were met. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who gained a minimum of 15 ETDRS letters from baseline at month 24. After month 24, subjects initially randomized to sham therapy were treated with ranibizumab 0.5 mg monthly. Two- and 3-year results have been reported.20,21 The proportion of subjects meeting the primary outcome threshold at 3 years was 19% to 22% in the sham/ ranibizumab 0-5-mg group, 37% to 51% in the ranibizumab 0.3-mg group, and 40% to 42% in the ranibizumab 0.5-mg group. Both groups receiving initial ranibizumab did better than the group receiving initial sham therapy (P≤.0026), and the sham group did not catch up to the 2 active groups after crossing over to ranibizumab therapy after year 2 (Figure 4). neovascular AMD? Dr Slakter: In the past 8 years we have been fortunate to see the introduction of anti-VEGF drugs that have fundamentally altered the potential for visual outcomes in people with exudative AMD. A thorough understanding of the utility of each of these 3 drugs, as well as of the value of the different treatment regimens, is critical in delivering optimal care to our patients. Dr Ho: We and our patients benefit from several effective anti-VEGF therapies approved for neovascular AMD. In general, our panel prefers on-label medication (aflibercept or ranibizumab) as an initial agent and generally employs a treat-and-extend approach. There is some wariness regarding systemic safety concerns of offlabel use of bevacizumab, but all our panelists agree that this is not proven; further, there is some inherent risk of a compounded medication. Nevertheless, each panelist uses off-label bevacizumab in his practice to varying degrees. Unlike in AMD, the 0.3-mg dose of ranibizumab was at the top of the dose-response curve and was approved by the FDA for DME. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCRnet) also has conducted a series of studies evaluating anti-VEGF therapy for DME, of which its Protocol I is of interest. This study assigned patients to 4 treatment groups: sham injection plus prompt laser, ranibizumab 0.5 mg plus prompt laser, ranibizumab 0.5 mg plus laser deferred for at least 24 weeks, triamcinolone 4 mg plus prompt laser. Retreatment was available if prespecified criteria were met. The primary outcome was the change from baseline in ETDRS VA at 12 months. The 1-year,22 2-year,23 and 3-year24 results have been reported (Table 2). There is general consensus that aflibercept may have the greatest durability among our treatment options. It is unclear whether switching agents in the setting of unresponsive or previously responsive patients provides meaningful visual benefit in our most challenging patients; there is more evidence of anatomic benefit, although these data are still evolving. There is no real consensus on an end point for treatment with anti-VEGF therapy; some clinicians treat indefinitely while others treat PRN. Briefly, RISE and RIDE enrolled patients with diabetes who had macular edema and VA of 20/40 or worse and randomized them to receive either sham injections or ranibizumab in a 0.3-mg or 0.5-mg dose. Rescue laser was 20 10 12.4 11.2 11.7 5 4.5 0 -5 2.5 Day 7 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 Month Subgroup of patients receiving ≥ 1 st Figure 4. Three-year VA outcomes in the RISE and RIDE 20 studies of diabetic macular edema.21 RIDE Reprinted with permission from Elsevier. 13.9 15 13.0 12.8 13.1 10 7.5 5 4.5 0 50 n CFT, µm 12.0 15 -5 10 RIDE RISE Pooled Mean change in CFT, µm in that, for DME, there was an established effective treatment—laser photocoagulation—before the advent of anti-VEGF therapy. Thus, a higher threshold has been established for a paradigm shift in DME: a new treatment has to be better than the existing treatment in order for a paradigm shift to occur. Numerous studies have demonstrated that anti-VEGF therapy is, in fact, better than laser therapy for the management of DME. Among these, the RISE and RIDE trials were the registry trials that led to ranibizumab’s approval for the management of DME. Mean BCVA change, ETDRS letters Dr Ho: Diabetic macular edema differs from AMD Mean BCVA change from baseline, letters DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA RIDE and RIS Day 7 0 RIDE 6 12 18 24 30 36 Month 0 -50 -100 -147.0 -1 Table 2. Mean ETDRS Letter Gains at 1, 2, and 3 Years From Baseline in DRCRnet Protocol I Evaluating Ranibizumab for DME.22-24 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Sham plus prompt laser +3 +3 — Raniibizumab 0.5 mg plus prompt laser +9 +7 +6.8 Raniibizumab 0.5 mg plus deferred laser +9 +9 Triamcinolone 4 mg plus prompt laser +4 +2 +9.7 — Additionally, 2 trials have evaluated the effect of aflibercept on DME. Dr Brown, please summarize the aflibercept VIVID and VISTA studies and provide some overall take-home messages from these anti-VEGF trials for DME. Dr Brown: VIVID and VISTA are the 2 ongoing registry trials of aflibercept for DME. In these studies, patients with DME received either aflibercept 2 mg monthly, aflibercept 2 mg every other month (after 5 monthly loading doses), or laser. The primary outcome was the mean change in ETDRS VA from baseline at 12 months. One-year results have been reported25 (Table 3). The take-home message from these studies is that aflibercept was superior to laser in restoring VA in eyes with DME. Table 3. Mean ETDRS Letter Gains at 1 Year From Baseline in the VIVID and VISTA Trials of Aflibercept for DME.25 VIVID VISTA Aflibercept 2 mg monthly +10.5 +12.5 Aflibercept 2 mg every other month +10.7 +10.7 Laser +1.2 +0.2 Dr Ho: We have no head-to-head data so far comparing these anti-VEGF agents for DME. The ongoing DRCRnet Protocol T study compares all 3 anti-VEGF agents head-tohead for DME and should be reported in approximately 1 year. In the meantime, how do we select first-line therapy for DME? Dr Brown: For those few patients who have small circinate areas of DME with obvious microaneurysms, laser is still my preferred approach. But most patients have more diffuse DME and will require anti-VEGF therapy. These eyes have large VEGF loads and require many injections to achieve and maintain VA improvement. Dr Slakter: Most of my patients have diffuse DME, and so anti-VEGF therapy is my first-line approach. The edema does not always resolve completely. After drying up most of the macula with anti-VEGF therapy, an FA may reveal a few focal microaneurysms that are amenable to laser treatment. Another reason that edema does not always resolve completely involves systemic disease control. I often see patients for second opinions after they have received 8 or 10 injections, and their HbA1c levels are 9, which is much too high. If you can motivate patients to eat better, lose weight, and control their blood glucose levels, the macular edema also is often easier to manage—such lifestyle changes make for a much better intervention than serial intravitreal injections. Dr Ho: That is an excellent point regarding our leverage to inspire our patients with diabetes to optimize their systemic and metabolic control in the battle against DME. Patients with diabetes mellitus fear blindness even more than premature death, and therefore we have unique leverage and opportunity to effect change in not only their ocular health but their systemic condition as well. Goals: blood pressure of 130/80 or better, A1C level of 7, and walking or equivalent cardio activity 30 minutes a day most days of the week. They need to hear these goals from us. A review of medications is important as well because some oral hypoglycemic agents, such as the oral glitazone drugs, can cause macular edema.26 Checking their medical status, checking their medications, and encouraging them to change behavior are all really important points. Because we know that patients can go blind from DME, we are in a powerful position to encourage self-care because people often value their vision above most other senses. Are there other thoughts on the selection of initial antiVEGF therapy for DME? Dr Brown: People with diabetes have systemic vascular disease and I am concerned that they may be at increased risk for adverse events associated with systemic VEGF suppression. For this reason, I typically start with ranibizumab if the patient’s insurance coverage allows. Dr Ho: Are there differences, in your clinical experience, between anti-VEGF agents for DME, recognizing that aflibercept is not commercially available at this time? Dr Avery: It is my clinical impression that ranibizumab works a little better than bevacizumab for DME. In addition to the ongoing DRCRnet study, there was recently a small prospective study comparing ranibizumab and bevacizumab for DME.27 There were some small differences in VA outcomes at various time points, but the 2 agents were 11 statistically equal in terms of efficacy at 12 months. The ranibizumab group required fewer injections than the bevacizumab group, however. Dr Ho: My experience is similar; ranibizumab seems to be a more effective agent than bevacizumab for DME and the differences are greater than for AMD. How do we handle suboptimal responders to anti-VEGF therapy for DME? Dr Slakter: I tend to start with ranibizumab. Suboptimal responders to anti-VEGF therapy are more common in DME than in AMD, in my experience. This occurrence may be due to the higher VEGF load in these ischemic eyes. I am less quick in DME to declare a patient a suboptimal responder. In AMD, there is an advantage to quickly achieving and maintaining a dry macula. In DME, these maculae are chronically edematous, and unless there are large cysts in the foveal region, they tolerate edema for a reasonable period of time. Therefore, I have a longer period of time to assess the effectiveness of therapy before feeling the need to switch to something different. When I do decide to switch therapy, I typically start by changing to a different anti-VEGF agent. Laser also can be effective if the macula becomes partially dry with VEGF inhibition. Steroids also can be useful, and to spare the patients frequent injections, the sustained-release dexamethasone implant can be useful in DME.28 Minimizing the treatment burden is even more important in DME than in AMD because unlike the older AMD patients who are typically retired, DME patients are usually still working, so there are added costs to the patient and to society from frequent visits to my office. Dr Avery: Along with reducing the treatment burden, I have found it helpful to add micropulse laser therapy in conjunction with anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with diffuse edema. We are exploring the value of this adjunct in our practice now, using systems that feature yellow and infrared lasers. Some have advocated using the infrared laser in a sub threshold fashion straight through the fovea.29 I am more conservative and do not treat the fovea, but it is nice to know that using certain sub threshold parameters, you may not cause damage if you get too close to the fovea. Dr Ho: Is there is a role for corticosteroids in eyes with recalcitrant DME? Dr Avery: The pathophysiology of DME is multifactorial and involves VEGF and inflammation dually driving the vascular permeability that results in edema. Steroids work in a complementary fashion with anti-VEGF agents to suppress the inflammatory component. There are, however, downsides to steroids—namely, the possible development of cataracts and glaucoma. Both of these situations can be managed if they arise. If anti-VEGF therapy alone cannot resolve DME, I frequently will add steroids, particularly in pseudophakic patients. In the previously mentioned DRCRnet Protocol I study, a subgroup analysis revealed that triamcinolone was just as effective in restoring vision as ranibizumab in pseudophakic patients.20 Dr Ho: There has been much publicity recently regarding the potential risks of compounded steroids, albeit in applications other than ocular disease. Given this issue, what steroid do you use if a patient does not respond to anti-VEGF therapy? Dr Avery: I no longer use compounded triamcinolone. I now use the branded triamcinolone product that is FDA approved and specifically formulated for intraocular use and is packaged in a single-use vial that all but eliminates the risk of contamination. This branded formulation of triamcinolone is not specifically approved for use in DME, but I feel more comfortable with it than with a compounded product. Dr Brown: I wanted to believe that we could deliver adequate levels of anti-VEGF agents into the eye to suppress the VEGF associated with DME. The truth, however, is that I have many patients in whom large quantities of anti-VEGF drugs are inadequate, but they respond very well to steroids. I have used triamcinolone in some patients, but once we have elected to use steroid therapy, I prefer to take advantage of a longer-acting steroid formulation to reduce the treatment burden. I use more of the dexamethasone implant. I wish the fluocinolone acetonide implant had been approved by the FDA for use in the United States; it is an approved indication in Europe. We participated in those clinical trials and some patients had long-term control with that device. However, the risk for glaucoma with the device—often requiring filtering surgery to control—was a safety issue that may have impeded its approval. Dr Ho: While anti-VEGF therapy is first-line treatment in my hands for patients with fovea involving DME, corticosteroids play an important role in eyes that respond 12 suboptimally; my preference is a noncompounded corticosteroid such as triamcinolone acetonide or the dexamethasone implant. Injecting corticosteroids is like pressing a reset button for DME; it can, for example, help an eye respond to anti-VEGF therapy. Does surgery play a role in patients with DME? Dr Avery: Vitrectomy certainly increases the oxygenation of intraocular tissues, which is beneficial in DME. But it also reduces the intravitreal half-life of any subsequently injected therapeutic agents. Vitrectomy is probably best suited for patients with vitreomacular traction or epiretinal membranes, in whom flattening the macula pharmacologically is very difficult. Dr Ho: Are we treating DME patients who have evidence of vitreomacular adhesions differently? Dr Slakter: Vitreomacular adhesions do pose an added component to the management of DME. I will consider surgery in patients who have little or no response to anti-VEGF therapy and in whom I believe vitreomacular traction is playing a major role in their disease process. I have to have a high suspicion that traction is at play in order to make it worthwhile to give up durability of anti-VEGF agents afterwards. I think there may be value in releasing the adhesions while removing as little vitreous as possible. This preserves the vitreous to serve as a depot for the drug if I need to continue injecting anti-VEGF therapy postoperatively. to maintain control of the DME. Are there other therapeutic options? Can we better control their blood sugar or their hypertension? Can we encourage our patients to lose weight? Are they on a glitazone hypoglycemic medication that may be aggravating their macular edema? Dr Avery: I think the pathophysiology of DME is different from that of AMD. In AMD, we are usually able to get the macula bone-dry and flat with anti-VEGF agents. Achieving that may not be as easy in some patients with DME. This is not necessarily a treatment failure if they maintain excellent vision. But given the other pathways involved in DME, I foresee adjunctive treatments playing a role as well. At present, though, anti-VEGF therapy has the best proven outcome. Dr Slakter: OCT is important in DME, but perhaps not as important as in AMD. There is more to diabetic eye disease than just macular edema, and there is more to diabetes than just diabetic eye disease. We have to be aware of proliferative neovascularization, and we have to be aware that diabetes is a systemic disease. The central subfield on the OCT does not tell the whole story in eyes with DME the way it does with eyes in AMD. Dr Ho: Before concluding this discussion, let us each Dr Ho: We now practice in the era of anti-VEGF therapy. Moreover, we have multiple agents from which to choose, and there may be some relevant differences between these agents that we are still teasing out in head-to-head clinical trials. The approaches to managing AMD and DME are quite similar in some regards, yet quite different in others. In AMD, we have fewer treatment options when anti-VEGF therapy inadequately controls the disease, whereas in DME, we have laser and steroids to help in suboptimally responsive patients. In some patients with DME and retinal interface abnormalities, surgery may play a role to improve their course of treatment. My pearl is to give your agent of choice longer time to show a benefit in DME than you do in AMD and to be more tolerant of DME. As new and ongoing trials report their findings, our ability to further individualize therapy for management of both AMD and DME will continue to improve. We should not forget that, particularly regarding those with diabetes, we see our patients far more often than do their primary care physicians, and so we have a distinctive opportunity to help them effect the lifestyle changes that can enhance their quality of life and our ability to adequately treat their eye disease. provide a clinical pearl for the management of DME in clinical practice. Mine is to keep in mind that our patients with DME are significantly younger than our patients with wet AMD, and their diabetes likely will be ongoing and lifelong because there is not yet a cure for the fundamental disease. In DME, the response to anti-VEGF therapy is more variable than in AMD. Visual acuity does improve with anti-VEGF treatment in DME, but more slowly than in AMD. Dr Brown: I try to consider the whole patient, particularly when he or she requires monthly injections 13 REFERENCES 1. CAT T Research Group, Mar tin DF, Maguire MG, Y ing GS, Gr unwald JE, F ine SL, Jaffe GJ. R anibizumab and be vacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897-1908. 2. Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CAT T ) Research Group, Mar tin DF, Maguire MG, F ine SL, et al. R anibizumab and be vacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmolog y. 2012;119(17):1388-1398. 3. IVAN S tudy Investigators, Chakravar thy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. Ranibizumab versus be vacizumab to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration: one-year findings from the IVAN randomiz ed tr ial. Ophthalmolog y. 2012;119(7):1399-1411. 4. Kodjikian L. O ver vie w of the GEFAL S tudy. Presented at: Annual Meeting of The Association for Research in V ision and Ophthalmolog y ; May 5-9, 2013; S eattle, WA. 5. Krebs I, S chmetterer L, Boltz A, et al; MANTA Research Group. A randomised double-masked tr ial compar ing the visual outcome af ter treatment with ranibizumab or be vacizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(3):266-271. 6. Berg K. Lucentis compared to Avastin study. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Amer ic an Ac ademy of Ophthalmolog y ; November 16-19, 2013; Ne w O r leans, LA. 7. Kahook MY, Liu L, R uz yc ki P, et al. High-molecularweight aggregates in repac kaged be vacizumab. Retina. 2010;30(6):887-992. 8. Aver y RI, Castellar in A, S teinle N, et al. Compar ison of systemic pharmacokinetics post anti-VEGF intravitreal injections of ranibizumab, be vacizumab and aflibercept. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Amer ic an S ociet y of Retina S pecialists; August 24-28, 2013; Toronto, Ontar io, Canada. 9. Heler JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al; VI EW 1 and VI EW 2 S tudy Groups. Intravitreal aflibercept ( VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmolog y. 2012;119(12):2537-2548. 10. S chmidt-Erfur th U, K aiser P K, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninet y-six-week results of the VI EW S tudies. Ophthalmolog y. 2014;121(1):193-201. 11. Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, et al; HARBOR S tudy Group. Twel ve-month effic ac y and safet y of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmolog y. 2013;120(5):1046-1056. 12. Patel KH, Chow CC, R athod R , et al. R apid response of retinal pigment epithelial detachments to intravitreal aflibercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration refractor y to bevacizumab and ranibizumab. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(5):663-667. 13. Miura M, I wasaki T, Goto H. Intravitreal aflibercept for pol ypoidal choroidal vasculopathy af ter de veloping ranibizumab tachyphylaxis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7: 1591-1595. 14. Brown DM, Heier JS, Ciulla T, et al; CLEAR-I T 2 Investigators. Primar y endpoint results of a phase I I study of vascular endothelial grow th factor trap-eye in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmolog y. 2011;118(6):1089-1097. 15. Heier JS, Boyer D, Nguyen QD, et al; CLEAR-I T 2 Investigators. The 1-year results of CLEAR-I T 2, a phase 2 study of vascular endothelial grow th factor trap-eye dosed as-needed af ter 12-week fixed dosing. Ophthalmolog y. 2011;118(6):1098-1106. 14 16. Koh A, L ee WK, Chen LJ, et al. EVEREST study : effic ac y and safet y of ver tepor fin photodynamic therapy in combination with ranibizumab or alone versus ranibizumab monotherapy in patients with symptomatic macular pol ypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina. 2012;32(8):1453-1464. 17. S ubfoveal neovascular lesions in age-related macular degeneration. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment in the macular photocoagulation study. Macular P hotocoagulation S tudy Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(9):1242-1257. 18. Bar baz etto IA, S orenson J, Gallego-Pinaz o R , Engelber t M. Aflibercept for patients previousl y treated with antiVEGF therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Amer ic an S ociet y of Retina S pecialists; August 25-29, 2012; L as Vegas, NV. 19. S hah CP, Cho H, Br yant JS, et al. Aflibercept for exudative AMD suboptimall y responsive to ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Amer ic an S ociet y of Retina S pecialists; August 25-29, 2012; L as Vegas, NV. 20. Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al; RISE and RIDE Research Groups. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomiz ed tr ials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmolog y. 2012;119(4):789-801. 21. Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, et al; RIDE and RISE Research Group. L ong-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: the 36-month results from two phase III tr ials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmolog y. 2013;120(10):2013-2022. 22. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinic al Research Network, Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Bec k RW, et al. Randomiz ed tr ial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or tr iamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmolog y. 2010;117(6):1064-1077.e35. 23. Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinic al Research Network. Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or tr iamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmolog y. 2011;118(4):609-614. 24. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinic al Research Network, Elman MJ, Qin H, Aiello LP, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: three-year randomiz ed tr ial results. Ophthalmolog y. 2012;119(11):2312-2318. 25. Regeneron and Bayer repor t positive one-year results from two phase 3 tr ials of EYLEA® (aflibercept) injection for the treatment of diabetic macular edema [press release]. Tarr ytown, NY: P RNewswire; August 6, 2013. http:// investor.regeneron.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=782911. Accessed December 13, 2013. 26. Fong DS, Contreras R . Glitaz one use associated with diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):583-586.e1. 27. Nepomuceno AB, Takaki E, Paes de Almeida FP, et al. A prospective randomiz ed tr ial of intravitreal bevacizumab versus ranibizumab for the management of diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(3):502-510.e2. 28. Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfor t R Jr, et al; OZURDEX GENEVA S tudy Group. Randomiz ed, sham-controlled tr ial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occ lusion. Ophthalmolog y. 2010;117(6):1134-1146.e3. 29. L uttr ull JK, S inc lair SD. S afet y of transfoveal subthreshold diode micropulse laser ( T F SDM) for intrafoveal diabetic macular edema (IF DME) in eyes with good visual acuit y. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Amer ic an S ociet y of Retina S pecialists; August 24-28, 2013; Toronto, Ontar io, Canada. POST TEST WORKSHEET Please go to http://bit.ly/neovascular14 to take the post test followed by course evaluations, after which you will be able to generate your CME certificate. Below are the post test questions. 1. Which 2 anti-VEGF agents did CATT compare? A. Bevacizumab and aflibercept B. Bevacizumab and ranibizumab C. Ranibizumab and aflibercept D. Bevacizumab and aflibercept 2. A key take-home message from CATT is: A. PRN dosing is superior to monthly dosing with either agent B. Aflibercept has more safety issues than does bevacizumab C. Bevacizumab and ranibizumab are equivalent in efficacy when dosed monthly D. Outcomes are the same when the drugs are dosed either monthly or every other month 3. Which of the following drugs used to treat AMD has the shortest systemic half-life in plasma? A .Bevacizumab B. Aflibercept C. Ranibizumab D. All 3 drugs have the same half-life 4. According to evidence provided by the VIEW studies, which anti-VEGF drug has durability of action that supports dosing every other month? A. Bevacizumab B. Aflibercept C. Ranibizumab D. Triamcinolone 5. A poor response to anti-VEGF therapy in an AMD patient should prompt an evaluation to uncover all the following potential conditions, except: A. Retinal pigment epithelial detachment B. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy C. Juxtafoveal telangiectasis D. Central serous chorioretinopathy 6. When a patient whose neovascular AMD was previously controlled with anti-VEGF therapy begins leaking again, a reasonable next step would be: A. Dose the same anti-VEGF agent, but less often to avoid tachyphylaxis B. Extend the interval between injections to reduce tolerance C. Increase the dose of the current anti-VEGF agent D. Increase the frequency of dosing of the current anti-VEGF agent or switch to a different agent 7. The current standard of care for treating DME is: A. Laser B. Steroids C. Anti-VEGF therapy D. Vitrectomy 8. Which of the following statements is false regarding the results of anti-VEGF trials in DME? A. Ranibizumab has been proven to be effective in clinical trials B. Aflibercept has been proven to be effective in clinical trials C. Head-to-head comparisons of anti-VEGF agents for DME have proven that they are equally effective D. Anti-VEGF therapy is more effective than laser therapy 9. A patient with DME responds suboptimally to initial anti-VEGF therapy. Explanations for such a response might include: A. Well-controlled systemic diabetes B. Use of glitazone hypoglycemic agents C. Recent weight loss D. Pseudophakia 10. Among the therapeutic options for a patient with DME who responds suboptimally to anti-VEGF therapy are: A. Laser B. Steroids C. Vitrectomy D. All the above are reasonable options in select patients 15 Individualizing Therapy for Patients With Neovascular AMD and DME: Considerations for Short- and Long-Term Management