* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download spiral nebulae

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

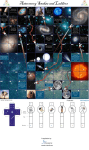

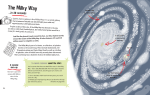

What Are the Spiral Nebulae? The State of Play Following Shapley and Oort, we knew that The galaxy is a big flat rotating system of stars But that’s all we knew. We did not know, for example, that it has a spiral stucture – proof of that only came in the 1950s. For all we knew, the Milky Way might still be a uniquely large object in the universe, with no counterparts at all. But Consider the So-Called Spiral Nebulae By the 1920s, astronomers knew of many spiral nebulae in the night sky. Their varied appearances convinced us that they are flat. And so is our Milky Way! Two obvious questions arise: 1. 2. Are the spiral nebulae also gigantic star systems like our own flattened Milky Way? Or might they instead be small objects (maybe solar systems in formation)? Is it possible that the Milky Way is itself a spiral? The‘Spiral Nebulae’ First sketched by Rosse (in 1845) - no photographic techniques back then! Eventually, Though One of the very earliest astronomical photographs Modern Images Are Of Course Much Better! M31, in Andromeda We See Them at Various Angles Close Up note the smaller [more remote?] spirals in the background The Dominant Belief in the early 1920s [just about a century ago] The general feeling was that there was only one galaxy, the Milky Way – a huge stellar system sometimes called our ‘universe.’ The spiral nebulae were thought to be something else, perhaps even solar systems in formation. They were believed to be small satellites of our own galaxy, subordinate to it. Shapley’s Belief The Key Question: Could This Be a Solar System in Formation? The Spiral Nebulae Were Thought to be Nearby [which implies that they must be small] There were two reasons for this belief. 1. Their distribution in space 2. Their apparent states of rotation 1. Their Spatial Distribution Suppose instead that the nebulae are huge (like our own Milky Way) and randomly distributed throughout a vast universe, then: we should see them all over the sky, in all directions (The ones will be relatively big and bright; many others will be smaller and faint) That’s Not What Was Seen! There is a So-Called ’Zone of Avoidance’ No spiral nebulae at all are seen in the broad coloured-in region of the sky! The ‘Zone of Avoidance’ Lies in a Special Location It is aligned with the plane of the Milky Way itself. The spirals, whatever they are, seem to ‘avoid’ the Milky Way! The Correct, Modern Understanding: Interstellar Obscuration We see small remote galaxies ‘above and below’ this nearby galaxy, but can’t see through it! Our own Milky Way likewise blocks our view. Dust Gets in the Way! We live in a gas-rich dusty galaxy with obscured views. Resolving the \Problem: Our Galaxy in Infrared Light (not possible in Shapley’s day!) Long wavelengths help cut though the interstellar‘fog.’ An Understandable Misinterpretation No one fully appreciated the effects of dust and obscuration, so the belief was that the spiral nebulae must be satellites of the Milky Way – objects that ‘avoid’ the densest parts of the galaxy for some reason. (Maybe they get disrupted by tidal forces?) 2. The Apparent Rotations of the Spiral Nebulae Some of the spiral nebulae seemed clearly to be rotating measurably. That in itself seemed sensible enough, as it would explain why the nebulae were flattened. (Indeed, we now know that they are indeed rotating, just as the Milky Way is.) But there is an important implication: for this rotation to be directly observable in the way reported, the nebulae must be small [for reasons to be explained] And the fact that we can see them the way we do, this in turn implied that they must be nearby How Was the Rotation Detected? It’s simple in principle: take several photographs, many years apart, and see if the dots of light change position systematically! (Do we see the ‘pinwheel’ turning?) Image 1 (say, 1910) Image 2 (1920) Would You Expect to See Rotation? If this spiral nebula pictured is indeed something like a solar system in formation, you would expect to see systematic rotation, in a consistent direction, whether clockwise or counter-clockwise. The brighter ‘dots’ in the nebula might be, say, something like ‘Jupiters in formation,’ and should orbit the growing star at the center fairly quickly. (The spiral arms might, for example, be trailing behind.) Adrian van Maanen’s ‘Discovery’ The arrows in this picture show the sense in which various features seemed to have moved, by comparison to an earlier picture. The actual amount of the motion was very small, nearly immeasurable – the arrows show the directions. That Kind of Motion is Fine on Small Scales… Pinwheels can spin very quickly – a few times a second! But Now Think Astronomically Could this object spin on a timescale of decades or centuries, as van Maanen’s observations implied? NO! -- Not If It’s Huge! If this object is indeed comparable to our Milky Way, it must be about one hundred thousand light years across. The path followed by an object travelling around and around the centre must be tens or hundreds of thousands of light years in length.` To give rise to the ‘observed’ rotational motions, over a period of just a decade or two, the stars within them would need to be moving very much faster than the speed of light -- which is simply not possible. So: The Enforced Conclusion If van Maanen’s observations of rotation are correct, the nebulae must be small objects (like solar systems, perhaps) and relatively nearby, since we see them in sone detail This suggests that they were presumably associated with the Milky Way, in the way Shapley believed. The Modern Understanding Quite simply, van Maanen’s careful measurements were simply wrong. Repeated tests have shown that no such motions can be detected. He probably ‘saw’ what he subconsciously expected to see. Can We Resolve the Question Once and For All? Let us determine the true distance to even one of the spirals! We will learn whether it is (a) a tiny satellite, or instead (b) a huge object comparable to the Milky Way. But how shall we accomplish this?