* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Module III Speaker Notes - Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home

Birth control wikipedia , lookup

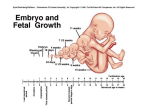

Maternal physiological changes in pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Breech birth wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal development wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal testing wikipedia , lookup