* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Eyeing Macular Degeneration — A Few Inflammatory Remarks

Cancer immunotherapy wikipedia , lookup

Inflammation wikipedia , lookup

Globalization and disease wikipedia , lookup

Innate immune system wikipedia , lookup

Germ theory of disease wikipedia , lookup

Multiple sclerosis research wikipedia , lookup

Psychoneuroimmunology wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

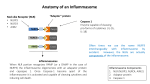

Behçet's disease wikipedia , lookup

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e clinical implications of basic research Eyeing Macular Degeneration — A Few Inflammatory Remarks James T. Rosenbaum, M.D. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the world’s leading cause of the loss of central vision. It is usually classed as one of two forms: a dry form, characterized by the appearance of drusen (Fig. 1), which are proteinaceous collections at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium, and by atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium; and a wet form, in which neovascularization complicates the retinal changes. Like several other chronic, progressive diseases associated with aging (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis), inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of AMD. The role of inflammation is supported by the detection of products of the immune system in the drusen themselves1 and by the results of genomewide association studies, which have implicated several components of the complement cascade in the pathogenesis of this disease.2 Two recent publications, one by Doyle et al.3 and the other by Tarallo et al.,4 have shown that NLRP3, a component of the innate immune system that senses danger-associated molecular patterns, is implicated in macular degeneration. The two studies are remarkably similar and remarkably different. Mutations in NLRP3 have been identified as the cause of uncommon autoinflammatory diseases known as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes.5 NLRP3 joins with two other cytoplasmic proteins, ASC and procaspase-1, to form a complex called the inflammasome. The inflammasome, in turn, activates the enzyme caspase 1, which goes on to activate several intracellular proteins, including interleukin-1β and interleukin-18. Insights gained from studies of the rare cryopyrin-associated periodic diseases have thus clarified the function of NLRP3 and have contributed to the appreciation that relatively common diseases such as gout and pseudogout are also mediated by the inflammasome. Doyle et al. found that drusen themselves activate NLRP3 (Fig. 2). Activation is also induced 768 Figure 1. Ophthalmoscopic View of the Retina and Optic Nerve in Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). The irregularly shaped yellow deposits (arrows) are drusen. An arrowhead points to the optic nerve. Drusen are characteristic of both wet and dry AMD. Choroidal neovascularization, the hallmark of wet AMD, is absent in this photo; accordingly, this represents dry AMD. by the complement component C1Q or enhanced by carboxyethylpyrrole, a protein modified by oxidative stress. Tarallo et al. also found that NLRP3 is activated in patients with AMD, but this group used an RNA motif known as an Alu repeat to activate the inflammasome in mouse and tissueculture studies. They had previously reported evidence supporting a role for Alu repeats in the pathogenesis of AMD. Together, the two investigative teams have expanded the list of potential triggers of caspase 1 — a list that already includes such diverse chemicals as uric acid and aluminum hydroxide. In most instances in which the inflammasome is activated, interleukin-1 becomes the major n engl j med 367;8 nejm.org august 23, 2012 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by Joyce Miller on August 28, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. clinical implications of basic research Figure 2. The NLRP3 Inflammasome and Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). Two studies recently implicated NLRP3, a component of the inflammasome, in AMD. One of these studies3 suggested that NLRP3 expressed in myeloid cells inhibits choroidal neovascularization and thus protects against AMD. The other study4 suggested that the activation of NLRP3 in the retinal pigment epithelium leads to atrophy of this structure. Local factors that activate NLRP3 include drusen, C1Q, Alu repeats, and carboxyethylpyrrole. Activated NLRP3 activates caspase-1, which activates interleukin-18, and this in turn could disrupt choroidal neovascularization or destroy the retinal pigment epithelium. “protagonist.” For example, the inherited diseases caused by mutations in NLRP3 were nearly untreatable until recently, but they are now known to respond dramatically to interleukin-1 blockade. Surprisingly, therefore, both groups concluded that the major consequence of activation of the inflammasome in the retina is the production of interleukin-18. Doyle et al. believe that the source of this cytokine is probably myeloid cells. Although NLRP3 is usually expressed predominantly in bone marrow–derived cells, Tarallo et al. contend that the retinal pigment epithelium is primarily responsible for interleukin-18. (Interleukins, of which there are more than 36, are cytokines named for their role in communication among leukocytes, but their expression is not confined to leukocytes.) The two groups arrived at opposite conclusions about the consequence of interleukin-18 in AMD. Tarallo and colleagues found that interleukin-18 promotes damage to the retinal pigment epithelium in a mouse model that mimics aspects of the dry form of AMD. Doyle and colleagues used a mouse model of choroidal neovascularization, the hallmark of wet AMD, and concluded that interleukin-18 inhibits new vessel formation; atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium is not prominent in their model. Thus, one group of authors concludes that inflammation in AMD is harmful and the other concludes that inflammation is beneficial. It is possible that both groups are right and that interleukin-18 has a dual role in AMD. If so, interleukin-18 as a therapeutic agent will present a Faustian dilemma, since delivering it might have both a favorable action (i.e., blocking neovascu- n engl j med 367;8 nejm.org august 23, 2012 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by Joyce Miller on August 28, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 769 clinical implications of basic research larization) and an unfavorable action (i.e., destroying the retinal pigment epithelium) in the posterior portion of the eye. Inhibiting interleukin-18 might salvage the retinal pigment epithelium while promoting new vessel growth. As the biology is clarified, new targets downstream from interleukin-18 will likely emerge. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. From the Departments of Ophthalmology, Medicine, and Cell Biology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. 1. Mullins RF, Russell SR, Anderson DH, Hageman GS. Drusen associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain proteins common to extracellular deposits associated 770 with atherosclerosis, elastosis, amyloidosis, and dense deposit disease. FASEB J 2000;14:835-46. 2. Edwards AO, Ritter R III, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science 2005;308:421-4. 3. Doyle SL, Campbell M, Ozaki E, et al. NLRP3 has a protective role in age-related macular degeneration through the induction of IL-18 by drusen components. Nat Med 2012;18:791-8. 4. Tarallo V, Hirano Y, Gelfand BD, et al. DICER1 loss and Alu RNA induce age-related macular degeneration via the NLRP3 inflammasome and MyD88. Cell 2012;149:847-59. 5. Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 2001;29:301-5. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1204973 Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. n engl j med 367;8 nejm.org august 23, 2012 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by Joyce Miller on August 28, 2012. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.