* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Guidelines on chronic kidney disease

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

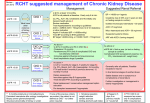

Chronic kidney disease_SS/NH 27/02/2007 Forum 12:23 Page 1 Clinical Review Guidelines on chronic kidney disease The relationship between CKD and cardiovascular disease is very important, write Liam Glynn et al CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD) is becoming an increasingly common diagnosis. In the US alone, there are over 400,000 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) with nearly 10 times this number having mild CKD defined as a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60ml/min/1.73m2.1 Even more disturbingly, the current number of patients with early CKD – the pool from which future ESRD patients will emerge – exceeds the present number with ESRD by a factor of 30 to 60.2 Risk factors for the development of CKD include age, smoking, hypertension and diabetes. The relationship between CKD and cardiovascular disease is a very important one. Cardiovascular disease is frequently associated with CKD, and individuals with CKD are more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than to develop kidney failure. Cardiovascular disease in CKD is treatable and potentially preventable, and CKD appears to be a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease.3 It is now recognised that even mild degrees of renal insufficiency are strongly associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and that CKD goes unrecognised in many individuals due to the asymptomatic nature of the condition. Indeed, where CKD is recognised in this population, patients are often nihilistically treated.4, 5 Despite the recognised association between reduced estimated GFR and poorer prognosis, risk factor management is often not optimised for such patients in the community setting5 while screening for CKD is frequently limited to a measurement of serum creatinine which does not accurately reflect GFR,6-7 the best indicator of renal function in health and disease.8 Physicians worldwide recognise the importance of cardiovascular risk factors and strive to identify and improve them in their patients. Despite the high prevalence of CKD in this population,9 it remains outside the group of well-recognised cardiovascular risk factors in many healthcare settings. This is despite the growing body of evidence demonstrating increased cardiovascular risk associated with CKD in the general population,10, 11 as well as in patients post-myocardial infarction,9, 12-14 post cardiac intervention15 and those with diabetes.16 However, the health systems of only a minority of countries have emphasised the importance of CKD screening (using estimated GFR) within primary care.17, 18 Remarkably, with CKD representing the group at highest risk from cardiovascular complications, even above diabetes, there has been a systematic exclusion of patients with CKD 60 FORUM March 2007 from therapeutic trials.19 Most primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease happens in the community and therefore it is important that we as primary care physicians become proactive in diagnosing and managing CKD in its most relevant setting. In an effort to support this process, a group of Irish nephrologists, GPs and endocrinologists, using several internationally recognised sources,18, 20, 21 have developed CKD guidelines for primary care which are summarised below: Why is CKD important to you and your patients? CKD is common and is often unrecognised in many patients due to the asymptomatic nature of the condition. CKD is strongly associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is a useful measure of renal function and can be calculated easily in clinical practice using serum creatinine, age, gender and race. Reduced eGFR is a potent marker for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and should be regarded as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease just like hypertension, cholesterol level, diabetic status, etc. The vast majority of patients with mild to moderate CKD will not require dialysis and can be managed in primary care. Appropriate management of patients with CKD in primary care may reduce overall cardiovascular risk and delay progression to renal failure. Classification of CKD Table 1 describes the classification of CKD as outlined by the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative.20 The classification of CKD is based on the use of an ‘estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate’ (eGFR) which is usually represented in the units of ml/min/1.73m2. eGFR can be calculated simply by using the patient variables of age, gender, serum creatinine and race. As a result, an increasing number of clinical biochemistry laboratories nationally are automatically calculating eGFR as part of each urea and electrolytes (U+E) request. Referral information The following information should be included in any referral to secondary care: • General medical history • Urinary symptoms • Medication history • Examination, e.g. blood pressure, oedema, palpable bladder or other positive findings • Urinalysis for blood and protein • In all patients who have persistent dipstick – positive pro- Chronic kidney disease_SS/NH 27/02/2007 12:24 Page 2 Forum Clinical Review Table 1 Stages of chronic kidney disease The stages of CKD as outlined by the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative GFR (ml/min/1.73m 2) Stage Clinical Featur es I *Kidney damage with normal or increased GFR ≥ 90 II *Kidney damage with a mild decrease in GFR 60-89 III Moderate decrease in GFR 30-59 IV Severe decrease in GFR 15-29 V Kidney failure < 15 or dialysis *Other evidence of kidney damage may include any of the following: • Persistent microalbuminuria/proteinuria/haematuria • Structural abnormalities of the kidneys demonstrated on ultrasound scanning or other radiological tests, eg. polycystic kidney disease, reflux nephropathy • Biopsy-proven chronic glomerulonephritis Patients found to have an eGFR of ≥ 60mL/min/1.73m2 without one of these markers: • Should not be considered to have CKD and • Should not be subjected to further investigation (unless there are additional reasons to do so, see ‘criteria for referral’) In the following circumstances eGFR may not be accurate: • Acute renal failure • Patients less than 18 years of age • Patients with advanced muscle-wasting and amputations • Pregnancy teinuria, check spot urine protein/creatinine (PCR) ratio. In diabetes patients with negative dipstick, check spot urine albumin/creatinine (ACR) ratio • Relevant blood results: U+E: urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate; eGFR; liver profile (albumin); bone profile: calcium, phosphate; fasting cholesterol and glucose; HbA1c (in diabetes); full blood count • All previous serum creatinine results with dates • Result of renal ultrasound scan if available. Laboratory assessment of CKD Calculation of eGFR eGFR is calculated from the serum creatinine value and patient variables such as age, gender, race. The most commonly used estimation equation is the abbreviated Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation:22 Estimated GFR (ml/min) = 186 x (serum creatinine level [in milligrams per deciliter]) – 1.154 x (age [in years]) – 0.203. For women and those of Afro-Caribbean decent (ethnicity data was collected during follow-up), the product of this equation is multiplied by correction factors of 0.742 and 1.21, respectively.22 Urinalysis Haematuria by dipstick is always significant and usually does not need verification by other tests. Proteinuria does need to be quantified so as to further stratify patients, (ie. nephrotic versus subnephrotic range proteinuria). Urine dipsticks are a useful screening tool, although they only provide a semi-quantitative assessment of level of proteinuria, as the reported value can vary according to the hydration status of the patient. Spot urine samples can be used to measure the PCR allowing the correction for hydra- tion status. The ACR is useful for the detection of small levels of proteinuria in diabetes patients and is not useful for routine follow-up of patients who already have established macroalbuminuria. Management and referral guidelines The chief goals of management of CKD are to delay progression to renal failure, to reduce overall cardiovascular risk and to avoid complications. Guidelines for CKD evaluation, treatment goals and referral guidelines are summarised in Table 2. Regular reviews are recommended and should consist of blood pressure measurement, assessment of kidney function, review of all medications, and immunisation with influenza vaccine and pneumococcal vaccine. Review all medications when renal insufficiency is first identified and avoid potentially nephrotoxic medications (eg. NSAIDs, COX inhibitors and contrast media). Risk factors for the development of CKD such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus should be specifically targeted. Cardiovascular complications can be reduced by attention to smoking cessation, weight loss, regular aerobic exercise, thrombotic risk (consider aspirin) and treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Anaemia is common and a target of > 11.5gm/dl should be sought. Hypertension Target blood pressure is < 130/80mmHg and lower targets may be appropriate in patients with diabetes or proteinuria. A low salt diet (< 100mmol (2.4 grams) sodium per day) is recommended and ACE inhibitors or ARBs are first choice medication and should be increased to maximum tolerated dose as necessary. Serum creatinine and potassium should be monitored during treatment and most patients will need more than two medications for optimal control. FORUM March 2007 61 Chronic kidney disease_SS/NH 27/02/2007 12:25 Page 3 Forum Clinical Review Table 2 Summary of CKD evaluation, treatment goals and referral guidelines CKD stage eGFR I > 90ml/min/1.73m2 Frequency of eval. Evaluation 12 months Treatment Referral Exam + BP Referral not (with proteinuria or U+E warranted unless haematuria) eGFR 1) BP <130/80 other problems present 60-89ml/min/1.73m2 II 12 months (with proteinuria or ACR/PCR Urinalysis haematuria) III 30-59ml/min/1.73m2 2) ACEi/ARB if no CI 3) Statin if CVD risk > 20% over 10 years 6-12 months As above + FBC, PTH, Ca, P, Albumin 4) Aspirin if no CI 5) Diabetics: optimise glycaemic control IV 15-29ml/min/1.73m2 V < 15ml/min/1.73m2 3-6 months 1-3 months Type 2 diabetes Target HbA1C is < 7.0% and again, ACE inhibitors or ARBs are the first choice in patients with hypertension and/or (micro) albuminuria and should be increased to maximum tolerated dose as necessary. Target a reduction in proteinuria and avoid the use of metformin when eGFR < 60ml/min. Conclusions Automated searching of general practice computer records can provide a reliable and valid way of identifying people with CKD who could benefit from interventions readily available in primary care.23 However, poor physician awareness of CKD and its association with excess cardiovascular morbidity and mortality remains a significant problem.24 The very low rate of recording of CKD in patients found to have CKD indicates scope for improving detection and early intervention.25 It appears that both traditional (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking etc) and non-traditional risk factors (elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6;26 elevated plasma homocysteine and abnormal apolipoprotein levels;27 anaemia;28 and arterial calcification29 among others) promote the frequent development of cardiovascular disease in the CKD population. This means that therapies targeting both progression of CKD and comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease are required to reduce mortality among these patients.24 As chronic disease management moves to the community, there are understandable concerns regarding the increasing numbers of patients and associated workload. eGFR may be a useful tool to prioritise the management of certain patients with established heart disease in the community. As the cardiovascular disease/CKD population continues to rise, strategies to improve survival for this group become increasingly critical. In fact, several studies suggest that these individuals may 62 FORUM March 2007 As for III h eGFR 15%/yr i Creat. 15%/yr BP > 150/90 on 3 meds PCR ≥ 100 unexplained anaemia Micro.haematuria Discussion with or urgent referral to nephrologist As for III derive as much, if not more, benefit from evidence-based cardiovascular therapies and strategies.30 This suggests that estimated GFR should be added to the list of dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, central obesity, and sedentary lifestyle as a significant and potentially modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The fact that estimated GFR appears to discriminate prognosis emphasises the importance of including estimated GFR in any cardiovascular risk factor profile for this group of patients. This also highlights the potential role of primary care physicians in risk factor assessment and management decision-making for patients with CKD. Liam G Glynn, GP principal, Ballyvaughan, Co Clare and lecturer in primary care, Department of General Practice, NUI, Galway; Donal Reddan, consultant nephrologist, Department of Medicine, Merlin Park Regional Hospital, Galway; Liam Hayes, GP principal, Tralee, and GP specialist in nephrology, Tralee General Hospital, Co Kerry; Liam Casserly, consultant nephrologist, Mid-Western Regional Hospital, Limerick; Austin Stack, consultant nephrologist, Regional Kidney Unit, HSE North West Letterkenny, Co Donegal; George J Mellotte, consultant nephrologist, Tallaght Hospital, Dublin The CKD guidelines discussed above have been developed by a group of Irish nephrologists, general practitioners and endocrinologists with the support of Roche pharmaceuticals and specifically with the help of Yvonne D’Arcy and Clare Blaney. The guidelines will be available for download from the ICGP website (www.icgp.ie) after they are launched on the March 8, World Kidney Day, at the Royal College of Physicians in Dublin. References on request

![CKD talk[1].15.09 - Jacobi Medical Center](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/003340080_1-9b582fb6e77d5fad41f81c427bfa5f30-150x150.png)