* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Physio pages use this.indd - Physiotherapy New Zealand

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

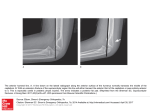

Anatomy in Practice The posterior triangle of the neck: Where is scalenus anterior? Ewan Kennedy BPhty PhD candidate, Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand Susan Mercer BPhty (Hons) MSc PhD Associate Professor, School of Biomedical Sciences University of Queensland Brisbane, Australia ABSTRACT In the physiotherapeutic literature scalenus anterior has been depicted as palpable and measurable by surface electromyography (EMG) within the posterior triangle of the neck, but without explaining in detail how this is achieved. The purpose of this study is to present the topographical anatomy of scalenus anterior in the posterior triangle of the neck, and consider the techniques of palpation and surface EMG from an anatomical perspective. The location of scalenus anterior within the posterior triangle was reviewed in anatomical textbooks and research literature, a dissection of a single embalmed cadaver (male, 64 years) and gross observation of transverse E12 plastinated slices. These resources revealed that the muscle belly of scalenus anterior is located below the level of C6 deep in the root of the neck, covered by various structures including the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and a substantial fat pad. This location suggests that neither palpation nor surface EMG recording of scalenus anterior is straightforward. Clinicians and researchers utilising these techniques should be aware of the topographic anatomy, and demonstrate this in a detailed methodology. This will help ensure that the techniques presented are both realistic and accurate, which are key aspects of evidence based practice. Kennedy E, Mercer S (2006): The posterior triangle of the neck: Where is scalenus anterior? New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy 34(3): 142-146. Key words: Neck muscles, scalenus anterior, palpation, clinical anatomy INTRODUCTION The posterior triangle of the neck (lateral cervical region) is a complex region, spiralling from the back of the skull to the clavicle anteriorly between the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles. Due to its spiral shape illustrations often distort the appearance of the triangle (Last 1978), making an accurate perception of depth difcult. Structures in this region commonly assessed by clinicians include the cervical lymph nodes, external jugular vein, brachial plexus, SCM and scalenus muscles. The surface anatomy of these structures is not simple, particularly for the scalenus muscles which form the deepest aspect of the oor of the triangle. Physiotherapists tend to primarily be concerned with the muscles in the posterior triangle, which is reected in the physiotherapeutic literature. Many authors describe techniques for locating or palpating the scalene muscles (Brantigan and Roos 2004, Falla et al 2002a, Gross et al 2002, Kostopoulos and Rizopoulos 2001, Portereld and DeRosa 1995, Senjyu et al 2002). However these authors tend to present palpation of the scalenus muscles as straightforward, with little reference to the anatomy of the region. Falla et al (2002a) published a method for recording electromyographic (EMG) activity in scalenus anterior using surface electrodes. The authors positioned the electrodes based on palpation of the muscle belly of scalenus anterior, without 142 describing in detail where palpation occurred with reference to anatomical landmarks. A large number of research articles have since been published utilising the same methodology (Falla et al 2002b, Falla et al 2003a, Falla et al 2003b, Falla et al 2004a, Falla et al 2004b, Falla et al 2004c, Falla et al 2004d, Falla et al 2004e, Falla et al 2004f), constituting a substantial proportion of recent physiotherapeutic literature pertaining to the cervical spine. A detailed knowledge of topographical anatomy is essential to accurate palpation, particularly for scalenus anterior as it has a conceptually difcult location in the root of the neck. Considering the complexity of the posterior triangle and the amount of physiotherapeutic literature utilising palpation to locate scalenus anterior, this technique deserves to be examined further. The purpose of this study is to present the topographical anatomy of scalenus anterior in the posterior triangle of the neck, and consider the techniques of palpation and surface EMG from an anatomical perspective. ANATOMY OF THE POSTERIOR TRIANGLE To appreciate the depth, location, relations and variations of structures in this area various anatomical resources were consulted including anatomy texts, the research literature, a dissection of a single embalmed cadaver (male, 64 years), and NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – November 2006, Vol. 34 (3) transverse E12 plastinated slices. These resources provide a number of different perspectives, and complement each other to present a comprehensive picture of the anatomy of the region. Textbook Anatomy The posterior triangle of the neck is formed between the posterior edge of the SCM and the anterior edge of the trapezius muscle (Figure 1). The base of the triangle is formed by the medial third of the clavicle, and the apex by the superior nuchal line of the occiput. The oor of the triangle comprises several parallel muscles covered by the prevertebral fascia (Bruce et al 1967, Drake et al 2005, Grant and Basmajian 1965, Last 1978, Moore and Dalley 2006, Wood Jones 1953, Woodburne and Burkel 1988, Zuckerman 1961). Figure 1. Lateral view of the posterior triangle of the neck (shaded area) formed between trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid. Notice the orientation of the muscles forming the oor the triangle. Within the triangle, between the overlying skin surface and the muscular oor, are numerous important structures. These include cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus supplying the skin overlying the posterior triangle; the platysma and omohyoid muscles; the spinal accessory nerve, which innervates the SCM and trapezius muscles; the deep cervical lymph nodes; the brachial plexus; and numerous arteries and veins – prominent is the external jugular vein (see Figure 2). For physiotherapists these structures are not usually of primary interest yet are important to note, particularly in post-surgical cases where these structures may have been affected. NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – November 2006, Vol. 34 (3) The muscular oor of the triangle comprises (from superior to inferior): splenius capitis, levator scapulae, and scalenus medius and posterior (Bruce et al 1967, Drake et al 2005, Grant and Basmajian 1965, Last 1978, Moore and Dalley 2006, Wood Jones 1953, Woodburne and Burkel 1988, Zuckerman 1961) (see Figure 1). Some texts also include scalenus anterior in the oor of the triangle (Drake et al 2005, Grant and Basmajian 1965, Wood Jones 1953), while others note that a small portion of semispinalis capitis may be visible at the apex of the triangle (Grant and Basmajian 1965, Last 1978, Wood Jones 1953, Zuckerman 1961). The location of scalenus anterior with respect to the posterior triangle is consistently reported in anatomical texts. While some texts include scalenus anterior in the muscular oor of the triangle all that specically state the location of scalenus anterior describe it as found deep to the posterior edge of the SCM (Bruce et al 1967, Grant and Basmajian 1965, Last 1978, Moore and Dalley 2006). Further detail is provided in Gray’s Anatomy (Standring 2005), which states that the clavicle, subclavius, SCM and omohyoid, lateral part of the carotid sheath, phrenic nerve, transverse cervical, suprascapular and ascending cervical arteries, subclavian vein, prevertebral fascia, and phrenic nerve are all anterior to scalenus anterior. Last (1978) observes that scalenus anterior is in fact a very slender muscle, a useful point when considering locating the muscle via palpation. Small details such as this are crucial to clinicians, yet are not often included in anatomical texts. Research Literature Consultation of the surgical literature conrms that scalenus anterior lies deep to the clavicular head of SCM, and gives further insight: Mattson (2004) in an article on the surgical approach to anterior scalenectomy clearly describes how the surgeon must progress through the skin, platysma, the clavicular head of SCM and a fat pad before scalenus anterior becomes visible. This type of description gives a precise insight into the layers of tissue lying between the skin and scalenus anterior, and is fundamental to good surgical practice. Clearly this approach to anatomy is also essential to realistic and accurate palpation in physiotherapy. Variations The scalene muscles are especially variable, and physiotherapists can clearly benefit from understanding some of the common variations that exist and how they may impact on clinical practice. Scalenus anterior is typically described as arising from the scalene tubercle of the rst rib and inserting into the anterior tubercles of C3-6 (Bruce et al 1967, Drake et al 2005, Grant and Basmajian 1965, Last 1978, Moore and Dalley 2006, Standring 2005). However the superior attachment sites of scalenus anterior are well known to vary in cervical level (Le Double 1897), while Wayman et al (1993) 143 also describe some variation in the position of the inferior attachment to the rst rib. In a study of variance in the relations of the brachial plexus and scalene muscles in cadavers Harry et al (1997) found such wide variation that only 14% of the specimens studied could be considered ‘normal’. Murakami et al (2003) even report a case of total absence of the right scalenus anterior muscle, a rare occurrence also observed by Le Double (1897). For more detailed information about the variations found in this region refer to Bergman et al (1984) or Le Double (1897). Cadaveric material In order to further examine the position of scalenus anterior in the posterior triangle of the neck we dissected this region in a single embalmed cadaver (male, 64 years). The skin, subcutaneous tissue, platysma and SCM were reected laterally to expose the posterior triangle, noting the insertions of the SCM for reference. The fat pad, lymphatic tissue and small vessels and nerves were then removed to expose scalenus anterior and other adjacent major structures. The extent to which the clavicular head of SCM covers scalenus anterior was clearly seen in situ (Figure 2). Immediately underneath the clavicular head of SCM the fat pad described by Mattson (2004) amounted to a signicant layer of tissue that took some time to remove cleanly. The superior aspect of scalenus anterior tapered, diverged and became tendinous before inserting into the anterior tubercles of the cervical vertebrae, and was covered by the lateral part of the carotid sheath. The muscle belly of scalenus anterior was located deep in the root of the neck surrounded by other signicant structures. The muscle was wedged between the carotid sheath antero-medially; and the brachial plexus and scalenus medius postero-laterally as shown in Figure 2. This deep, cramped location of scalenus anterior makes it an important landmark in dissection; Last (1978) in particular refers to scalenus anterior as the key to the root of the neck and describes its relations in great detail. However this will also make it very difcult to differentiate scalenus anterior from surrounding structures using palpation. Transverse E12 plastinated slices The thickness and depth of the structures overlying scalenus anterior are clearly demonstrated by transverse E12 plastinated slices (Figure 3). In this view the layers of tissue are clearly visible, as is the relative size and position of each structure. The clavicular head of SCM is revealed as a fairly substantial muscle bulk, and again seen to largely overlie scalenus anterior. Deep to the SCM the fat pad described by Mattson (2004) is 2-3cm thick, rich with small nerves and vessels. Also conrmed was the position of scalenus anterior between the carotid sheath and brachial plexus/ scalenus medius seen in our dissection. Viewing the transverse slices at T1, C7 and C6 reveals 144 Figure 2. Anterolateral view of a neck dissection showing the topographical position of scalenus anterior (ScA) in situ, wedged between the carotid sheath (CS) antero-medially; and the brachial plexus (BP) and scalenus medius (ScM) postero-laterally. The clavicular head of the SCM has been reected (dotted line marks the in situ position) and fatty and lymphatic tissue overlying the muscle removed to reveal the surface of scalenus anterior. Also note the position of omohyoid (Om) and the external jugular vein (EJV). the vertical extent of the muscle belly of scalenus anterior. The muscle belly of scalenus anterior can be clearly seen at the level of T1 soon after leaving the rst rib, dividing at C7, and greatly diminished at C6 as it tapers and becomes tendinous towards its insertions into the cervical transverse processes (Figure 3). Given this arrangement it should not be expected that the muscle belly of scalenus anterior could be found above the level of C6. CLINICAL ANATOMY Having considered the topographical anatomy of scalenus anterior in the posterior triangle, we can now reect on our ability to locate, palpate, or record EMG activity in this muscle using surface electrodes. When the location of scalenus anterior is considered, palpation no longer appears straightforward. Firstly the therapist must negotiate the clavicular head of SCM to reach the underlying tissues: palpating through this muscle will confound the accuracy of the technique, while palpating lateral to the clavicular head of SCM one is more likely to encounter scalenus medius/ NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – November 2006, Vol. 34 (3) will also make differentiating between scalenus anterior and these structures difcult. Some authors identify scalenus anterior with palpation during resisted neck exion (Falla et al 2002a) or with the neck laterally exed to the opposite side (Gross et al 2002). Contracting scalenus anterior is unlikely to assist in identifying this muscle unless the overlying clavicular head of SCM remains inactive, which is unlikely during resisted neck exion. Similarly any activity in platysma will make palpation of deeper structures extremely difcult. Contralateral exion of the neck will stretch all the tissues of the palpated side (i.e. muscles, fascia etc), an effect not specic to scalenus anterior. When stretched the supercial tissues (platysma in particular) will become more rigid and rm to the touch, making palpation of the deeply placed scalenus anterior more, rather than less, difcult. Recording EMG activity in scalenus anterior using surface electrodes appears even more complex than palpation. Positioning electrodes on the skin surface in such a way that scalenus anterior is the muscle in closest proximity appears extremely difcult (see Figures). The electrodes must be lateral to the clavicular head of SCM, below the level of C6 and able to differentiate the activity of scalenus anterior from surrounding muscles. In this small window scalenus anterior remains quite deep to the skin surface, while the curved skin surface likely precludes orienting the electrodes to the bre direction of the muscle. CONCLUSIONS Figure 3. Transverse E12 plastinated slices at the levels of C6, C7 and T1. These views demonstrate the size, shape and position of structures overlying scalenus anterior. Note how these features change at different levels, in particular the depth of scalenus anterior at the level of T1, and how its size diminishes by the level of C6. White arrowhead – scalenus anterior; Black arrowhead – scalenus medius/posterior; White asterisk – Sternocleidomastoid. posterior and levator scapulae (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Deep still to the clavicular head of SCM remain omohyoid and 2-3cm of fat pad. Also given that scalenus anterior tapers and becomes tendinous superiorly, the muscle belly of scalenus anterior will be found only below approximately the level of C6 (inferior to the cricoid cartilage) in the root of the neck. Considered together the muscle belly can be visualised as deep to the clavicular head of SCM and below the level of C6 in the root of the neck, a small window of opportunity. The wedged position of scalenus anterior between the carotid sheath and the brachial plexus/scalenus medius NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – November 2006, Vol. 34 (3) The topographical location of scalenus anterior was found to be deep and low in the root of the neck, underneath the clavicular head of SCM. When the anatomy of the posterior triangle is considered locating, palpating or recording EMG activity of scalenus anterior using surface electrodes appear far from straightforward. Clinicians and researchers utilising these techniques should be aware of the topographic anatomy, and demonstrate this in a detailed methodology. This will help ensure that the techniques presented are both realistic and accurate, which are key aspects of evidence based practice. Clinical anatomy remains a cornerstone of the physiotherapy curriculum, yet is perhaps undervalued in the physiotherapeutic literature. This article demonstrates the way in which anatomy relates to clinical and research practice, and continues to serve the profession as an important aspect of evidence based practice. Key points • In the physiotherapeutic literature scalenus anterior has been depicted as palpable and measurable by surface electromyography (EMG), but with little explanation of how this achieved • Scalenus anterior is located deep in the root of the neck, underneath the clavicular head of sternocleidomastoid 145 • When the anatomy of the region is considered locating, palpating or recording EMG activity of scalenus anterior using surface electrodes appear far from straightforward ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, University of Otago for access to the anatomical resources used in this study, in particular Russell Barnett for preparation of the E12 plastinated slices. Special thanks also to Robbie McPhee for his illustrative work. REFERENCES Bergman RA, Thompson SA, A AK (1984): Catalog of human variation. Baltimore: Urban and Schwarzenberg. Brantigan C and Roos D (2004). Diagnosing thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand Clinics 20: 27-36. Bruce J, Walmsley R and Ross J (1967): Manual of surgical anatomy. Edinburgh and London: E & S Livingstone. Drake RL, Vogl W and Mitchell AWM (2005): Gray’s anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone. Falla D, Dall’Alba P, Rainoldi A, Merletti R and Jull G (2002a). Location of innervation zones of sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles – a basis for clinical and research electromyography applications. Clinical Neurophysiology 113: 57-63. Falla D, Dall’Alba P, Rainoldi A, Merletti R and Jull G (2002b). Repeatability of surface EMG variables in the sternocleidomastoid and anterior scalene muscles. European Journal of Applied Physiology 87: 542-549. Falla D, Jull G, Dall’Alba P, Rainoldi A and Merletti R (2003a). An electromyographic analysis of the deep cervical exor muscles in performance of craniocervical exion. Physical Therapy 83 (10): 899-906. Falla D, Rainoldi A, Merletti R and Jull G (2003b). Myoelectric manifestations of sternocleidomastoid and anterior scalene muscle fatigue in chronic neck pain patients. Clinical Neurophysiology 114: 488-495. Falla D, Jull G, Rainoldi A and Merletti R (2004a). Neck exor muscle fatigue is side specic in patients with unilateral neck pain. European Journal of Pain 8: 71-77. Falla D, Rainoldi A, Jull G, Stavrou G and Tsao H (2004b). Lack of correlation between sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscle fatigability and duration of symptoms in chronic neck pain patients. Neurophysiologie clinique 34: 159-165. Falla D, Bilenkij G and Jull G (2004c). Patients with chronic neck pain demonstrate altered patterns of muscle activation during performance of a functional upper limb task. Spine 29 (13): 1436-1440. Falla D, Jull G, Edwards S, Koh K and Rainoldi A (2004d). Neuromuscular efciency of the sternocleidomastoid and 146 anterior scalene muscles in patients with chronic neck pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 26 (12): 712-717. Falla D, Jull G and Hodges P (2004e). Patients with neck pain demonstrate reduced electromyographic activity of the deep cervical exor muscles during performance of the craniocervical exion test. Spine 29 (19): 2108-2114. Falla D, Jull G and Hodges P (2004f). Feedforward activity of the cervical exor muscles during voluntary arm movements is delayed in chronic neck pain. Experimental Brain Research 157: 43-48. Grant JC, Basmajian JV (1965): Grants Method of Anatomy: By regions descriptive and deductive. (7th ed). Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company. Gross J, Fetto J and Rosen E (2002): Musculoskeletal examination. (2nd ed). USA; Blackwell Science. Harry W, Bennett JDC and Guha S (1997). Scalene muscles and the brachial plexus: Anatomical variations and their clinical signicance. Clinical Anatomy 10: 250-252. Kostopoulos D and Rizopoulos K (2001): The manual of trigger point and myofacial therapy. Thorofare, United States of America: SLACK Inc. Last RJ (1978): Last’s Anatomy: Regional and Applied. (6th ed). Edinburgh London and New York: Churchill Livingstone. Le Double AF (1897): Traite des variations du systeme musculaire de l’homme: et de leur signication au point de veu de l’anthropologie zoologique. Paris: Schleicher freres. Mattson RJ (2004). Surgical approach to anterior scalenectomy. Hand Clinics 20: 57-60. Moore KL and Dalley AF (2006): Clinically Oriented Anatomy. (5th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Murakami S, Horiuchi K, Yamamoto C, Ohtsuka A and Murakami T (2003). Absence of scalenus anterior muscle. Acta Medica Okayama 57 (3): 159-161. Portereld JA and DeRosa C (1995): Mechanical neck pain: Perspectives in functional anatomy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. Senjyu H, Yokohama S, Sukisaki T, Tanaka T, Honda S and Ohike T (2002). Assessment of the pattern of breathing using scalene palpation. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 18: 95-104. Standring S (2005): Gray’s Anatomy. The anatomical basis of practice (39th ed.). Spain: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. Wayman J, Miller S and Shanahan D (1993). Anatomical variation of the insertion of scalenus anterior in adult human subjects: implications for clinical practice. Journal of Anatomy 183: 165-167. Wood Jones F (1953): Buchanan’s manual of anatomy. (8th ed). London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox. Woodburne RT and Burkel WE (1988): Essentials of human anatomy. (8th ed). New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Zuckerman S (1961): A new system of anatomy. London: Oxford University Press. ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE Mr Ewan Kennedy: [email protected], Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, University of Otago. Dunedin, New Zealand. Tel: +64 3 479 5145 NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – November 2006, Vol. 34 (3)