* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download handbook to life in the aztec world

Tlaxcala City wikipedia , lookup

Texcoco, State of Mexico wikipedia , lookup

Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire wikipedia , lookup

Fall of Tenochtitlan wikipedia , lookup

Bernardino de Sahagún wikipedia , lookup

Tepotzotlán wikipedia , lookup

National Palace (Mexico) wikipedia , lookup

Templo Mayor wikipedia , lookup

Human sacrifice in Aztec culture wikipedia , lookup

Aztec warfare wikipedia , lookup

Aztec cuisine wikipedia , lookup

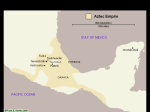

Aztec Empire wikipedia , lookup