* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

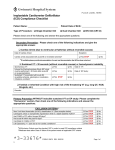

Download Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript