* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Functional and Content Words

Word-sense disambiguation wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Lojban grammar wikipedia , lookup

Classical compound wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Symbol grounding problem wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Agglutination wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho parts of speech wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Russian declension wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Untranslatability wikipedia , lookup

Transformational grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Junction Grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Contraction (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

ЎЗБЕКИСТОН РЕСПУБЛИКАСИ ОЛИЙ ВА ЎРТА МАХСУС

ТАЪЛИМ ВАЗИРЛИГИ

ЎЗБЕКИСТОН ДАВЛАТ ЖАҲОН ТИЛЛАРИ УНИВЕРСИТЕТИ

ИНГЛИЗ ТИЛИ БИРИНЧИ ФАКУЛЬТЕТИ

ИНГЛИЗ ТИЛИ ФОНЕТИКА ВА ФОНОЛОГИЯСИ КАФЕДРАСИ

Раҳматов Бекзод Ўктам ўғли

Functional words in the English language and the methods of their teaching

5220100 – Филология ва тилларни ўқитиш (инглиз тили) таълим

йуналиши бўйича бакалавр даражасини олиш учун

БИТИРУВ МАЛАКАВИЙ ИШИ

“ҲИМОЯГА ТАВСИЯ ЭТИЛАДИ”

ИЛМИЙ РАХБАР:

“Инглиз тили фонетика ва фонологияси”

_________ Д. Аликулова

кафедраси мудири

“____”___________2014 йил

_________М.Чўтпўлатов

“____”___________2014 йил

Тошкент – 2014

2

THE MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL

EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

UZBEKISTAN STATE UNIVERSITY OF WORLD LANGUAGES

THE FIRST ENGLISH LANGUAGE FACULTY

THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY

Rakhmatov Bekzod Uktam o’g’li

Functional words in the English language and the methods of their teaching

5220100 – Philology and teaching languages (The English language) for

granting bachelor’s degree

QUALIFICATION PAPER

QUALIFICATION PAPER

Scientific advisor:

IS ADMITTED TO DEFENCE

D.Alikulova

The Head of the Department of

“

English Phonetics and Phonology

M. Chutpulatov

“

”

2014

Tashkent - 2014

3

”

2014

CONTENT

Introduction…………………………………………………………………..…3

1.0 Chapter I. Review of the linguistic literature on the problem

of classifying the words into parts of speech

1.1. The Problem of parts of speech…………………..………………………....6

1.2. The principle of grouping the words into grammatical classes…….……...18

1.3. The syntactic-distributional classification of words……………………….25

2.0 Chapter II. Contextual-semantics of grammatical classification of words

used in P.Abraham’s “The Path of Thunder”

2.1. Grammatical classes of words……………………..……………………....28

2.2. From building means of parts of speech……………………………….......35

2.3. Type of grammatical meaning used in P.Abraham’s

“The Path of Thunder”…………………………………………………….……40

3.0 CHAPTER III. Aspects of teaching grammatical structure

3.1 Problems of teaching grammar………………………………………….….51

3.2 Teaching of grammatical classification of words to the elementary

and intermediate level students…………………………………………………58

4.0 Conclusion…………………………………………………….…………...67

5.0 Bibliography………………………………………………………………71

4

Introduction

“The main objective of all our reforms in the field of education is

individual. Therefore the task of education, the task of national renaissance will

remain the prerogative of the state and constitute a majority. For this, the power of

foreign languages also must work in new generation mind.”1

Conditions of reforming of all education system the question of the world

assistance to improvement of quality of scientific-theoretical aspect, educational

process is especially actually put. Speaking about the 23rd anniversary of National

Independence the President I.A.Karimov has declared in the program speech

“Harmoniously development of generation a basis of progress of Uzbekistan”:”

…all of us realize, that achievement of the great purpose put today before us,

noble aspirations, it is necessary for updating a society.” The effect and destiny of

our reforms carried out in the name of progress and the future, results of our

intentions are connected with highly skilled, conscious staff, the experts who are

meeting the requirements of time.2

Nowadays we are trying to establish a strong democratic state, of course,

with the help of the new generation. I also consider myself as one of the members

of this innovative people. I dare to say, foreign languages, especially English is a

good source to take the advantage. So, in this very qualification paper I tried to

make a good research work on the theme “Functional words in the English

language and methods of their teaching”.

The present qualification paper deals with the study of Functional words in

English and which present a certain interest both for the theoretical investigation

and for the practical language use.

The actuality of the investigation is explained on one hand by the profound

interest to the functional of the grammatical classification of words in the literary

From the President I.A.Karimov’s report at the Oliy Majlis session of the first convocation,February, 1995.

И.А.Каримов. Гармонично-развитое поколение-основа прогресса Узбекистана. Ташкент. 1998. Стр 158168

1

2

5

text and in speech, on the other hand by the absence of widely approved analysis

of the grammatical classification of words from the semantic, stylistic, structural

and translational points of view.

The novelty of the qualification paper is defined by concrete results of the

investigation. Special emphasis is laid on several of rendering the structural, the

stylistic features of functional words in English.

The aim of the qualification paper is to define the specific features of words

in the literary text and in speech as one of the important and complicated

functional words in English.

According to this general aim the following concrete tasks are put forward:

1. To analyze the linguistic literature on the problem of lexical features of

words.

2. To analyze actual problems the functional words in English.

5. To analyze the structural –semantic and functional characteristic of words

in English.

The methods of investigation used in this qualification paper are as

follows: oppositional, semantic, stylistic, structural, distributional, transformation,

immediate observation as well as the translation.

The practical value of the research is that the material and the results of

the given qualification paper can serve as the material for theoretical courses of

grammar, comparative typology, translation theory as well as can be used for

practical classes in oral and written speech practice, oral and written translation,

home reading, current events, and others.

The material includes: text books, monographs, articles, written by the

leading scholars, like: L.S Barkhudarov, M.Y.Blokh, V.Ya.Plotkin and etc.,

6

novels, short stories written by the American and British writers of the XXth

century, internet websites with corresponding headings and data base.

Theoretical importance of the qualification paper is determined by the

necessity of detailed and comprehensive analyzes of functional words in English

and the means of expressing the which are very of ten used in literature fluffing

various stylistic or pragmatic functions.

The structure of the word the given qualification paper consists of an

introduction, two chapter, a conclusion and bibliography.

7

1.0. CHAPTER I. Review of the Linguistic literature on the problem of

classifying the words into parts of speech

1.1. Word- as a Subject of Study

The morphological system of language reveals its properties through the

morphemic structure of words. It follows from this that morphology as part of

grammatical theory faces the two segmental units: the morpheme and the word.

But, as we have already pointed out, the morpheme is not identified otherwise

than part of the word; the functions of the morpheme are effected only as the

corresponding constituent functions of the word as a whole.

For instance, the form of the verbal past tense is built up by means of the

dental grammatical suffix: train-ed [-d]; publish-ed [-t]; meditat-ed [-id].

However, the past tense as a definite type of grammatical meaning is expressed

not by the dental morpheme in isolation, but by the verb (i.e. word) taken in the

corresponding form (realised by its morphemic composition); the dental suffix is

immediately related to the stem of the verb and together with the stem constitutes

the temporal correlation in the paradigmatic system of verbal categories

Thus, in studying the morpheme we actual study the word in the necessary details

or us composition and functions.

It is very difficult to give a rigorous and at the same time universal

definition to the word, i.e. such a definition as would unambiguously apply to all

the different word-units of the lexicon. This difficulty is explained by the fact that

the word is an extremely complex and many-sided phenomenon. Within the

framework of different linguistic trends and theories the word is defined as the

minimal potential sentence, the minimal free linguistic form, the elementary

component of the sentence, the articulate sound-symbol, the grammatically

arranged combination of sound with meaning, the meaningfully integral and

immediately identifiable lingual unit, the uninterrupted string of morphemes, etc.,

etc. None of these definitions, which can be divided into formal, functional, and

mixed, has the power to precisely cover all the lexical segments of language

without a residue remaining outside the field of definition.

8

The said difficulties compel some linguists to refrain from accepting the

word as the basic element of language. In particular, American scholars —

representatives of Descriptive Linguistics founded by L. Bloomfield —

recognised not the word and the sentence, but the phoneme and the morpheme as

the basic categories of linguistic description, because these units are the easiest to

be isolated in the continual text due to their "physically" minimal, elementary

segmental character: the phoneme being the minimal formal segment of language,

the morpheme, the minimal meaningful segment. Accordingly, only two

segmental levels were originally identified in language by Descriptive scholars:

the phonemic level and the morphemic level; later on a third one was added to

these — the level of "constructions", i.e. the level of morphemic combinations.

In fact, if we take such notional words as, say, water, pass, yellow and the

like, as well as their simple derivatives, e.g. watery, passer, yellowness, we shall

easily see their definite nominative function and unambiguous segmental

delimitation, making them beyond all doubt into "separate words of language".

But if we compare with the given one-stem words the corresponding composite

formations, such as waterman, password, yellow back, we shall immediately note

that the identification of the latter as separate words is much complicated by the

fact that they themselves are decomposable into separate words. One could point

out that the peculiar property distinguishing composite words from phrases is their

linear indivisibility, i.e. the impossibility tor them to be divided by a third word.

But this would-be rigorous criterion is quite irrelevant for analytical word forms,

e.g.: has met - has never met; is coming —is not by any means or under any

circumstances coming.

As for the criterion according to which the word is identified as a minimal

sign capable of functioning alone (the word understood as the "smallest free

form", or interpreted as the "potential minimal sentence"), it is irrelevant for the

bulk of functional words which cannot be used "independently" even in elliptical

responses (to say nothing of the fact that the very notion of ellipsis is essentially

the opposite of self-dependence).

9

In spite of the shown difficulties, however, there remains the

unquestionable fact that each speaker has at his disposal a ready stock of naming

units (more precisely, units standing to one another in nominative correlation) by

which he can build up an infinite number of utterances reflecting the ever

changing situations of reality.

This circumstance urges us to seek the identification of the word as a

lingual unit-type on other lines than the "strictly operational definition". In fact,

we do find the clarification of the problem in taking into consideration the

difference between the two sets of lingual phenomena: on the one hand, "polar"

phenomena; on the other hand, "intermediary" phenomena.3

Within a complex system of interrelated elements, polar phenomena are the

most clearly identifiable; they stand to one another in an utterly unambiguous

opposition. Intermediary phenomena are located in the system in between the

polar phenomena, making up a gradation of transitions or the so-called

"continuum". By some of their properties intermediary phenomena are similar or

near to one of the corresponding poles, while by other properties they are similar

to the other, opposing pole. The analysis of the intermediary phenomena from the

point of view of their relation to the polar phenomena reveals their own status in

the system. At the same time this kind of analysis helps evaluate the definitions of

the polar phenomena between which a continuum is established.

In this connection, the notional one-stem word and the morpheme should be

described as the opposing polar phenomena among the meaningful segments of

language; it is these elements that can be defined by their formal and functional

features most precisely and unambiguously. As for functional words, they occupy

intermediary positions between these poles, and their very intermediary status is

gradational. In particular, the variability of their status is expressed in the fact that

some of them can be used in an isolated response position (for instance, words of

3

Arnold I.V., The English Word, M.,1973,379p.

10

affirmation and negation, interrogative words, demonstrative words, etc.), while

others cannot (such as prepositions or conjunctions).

The nature of the element of any system is revealed in the character of its

function. The function of words is realised in their nominative correlation with

one another. On the basis of this correlation a number of functional words are

distinguished by the "negative delimitation" (i.e. delimitation as a residue after the

identification of the co-positional textual elements), e.g.-. the/people; to/speak;

by/way/of.

The "negative delimitation'' immediately connects these functional words

with the directly nominative, notional words in the system. Thus, the correlation in

question (which is to be implied by the conventional term "nominative function")

unites functional words with notional words, or "half-words" (word-morphemes)

with "full words". On the other hand, nominative correlation reduces the

morpheme as a type of segmental signee to the role of an element in the

composition of the word.4

As we see, if the elementary character (indivisibility) of the morpheme (as a

significative unit) is established in the structure of words, the elementary character

of the word (as a nominative unit) is realized in the system of lexicon.

Summing up what has been said in this paragraph, we may point out some of the

properties of the morpheme and the word which are fundamental from the point of

view of their systemic status and therefore require detailed investigations and

descriptions.

The morpheme is a meaningful segmental component of the word; the

morpheme is formed by phonemes; as a meaningful component of the word it is

elementary (i.e. indivisible into smaller segments as regards its significative

function).

The word is a nominative unit of language; it is formed by morphemes; it enters

the lexicon of language as its elementary component (i.e. a component indivisible

4

Arbekova T.I "English lexicology" M, 1977 p.243

11

into smaller segments as regards its nominative function); together with other

nominative units the word is used for the formation of the sentence — a unit of

information in the communication process.

In traditional grammar the study of the morphemic structure of the word

was conducted in the light of the two basic criteria: positional (the location of the

marginal morphemes in relation to the central ones) and semantic or functional

(the correlative contribution of the morphemes to the general meaning of the

word). The combination of these two criteria in an integral description has led to

the rational classification of morphemes that is widely used both in research

linguistic work and in practical lingual tuition.

In accord with the traditional classification, morphemes on the upper level

are divided into root-morphemes (roots) and affixal morphemes (affixes). The

roots express the concrete, "material" part of the meaning of the word, while the

affixes express the specification part of the meaning of the word, the

specifications being of lexico-semantic and grammatical-semantic character.

The

roots

of

notional

words

are

classical

lexical

morphemes.

The affixal morphemes include prefixes, suffixes, and inflexions (in the tradition

of the English school grammatical inflexions are commonly referred to as

"suffixes"). Of these, prefixes and lexical suffixes have word-building functions,

together with the root they form the stem of the word; inflexions (grammatical

suffixes) express different morphological categories.

The root, according to the positional content of the term (i.e. the border-area

between prefixes and suffixes), is obligatory for any word, while affixes are not

obligatory. Therefore one and the same morphemic segment of functional (i.e.

non-notional) status, depending on various morphemic environments, can in

principle be used now as an affix (mostly, a prefix), now as a root.

Cf.: out — a root-word (preposition, adverb, verbal postposition, adjective,

noun, verb); throughout — a composite word, in which -out serves as one of the

roots (the categorial status of the meaning of both morphemes is the same); outing

— a two-morpheme word, in which out is a root, and -ing is a suffix; outlook,

12

outline, outrage, out-talk, etc. — words, in which out- serves as a prefix; look-out,

knock-out, shut-out, time-out, etc. — words (nouns), in which -out serves as a

suffix.

The morphemic composition of modern English words has a wide range of

varieties; in the lexicon of everyday speech the preferable morphemic types of

stems are root-stems (one-root stems or two-root stems) and one-affix stems. With

grammatically changeable words, these stems take one grammatical suffix {two

"open" grammatical suffixes are used only with some plural nouns in the

possessive

case,

cf.:

the

children's

toys,

the

oxen's

yokes).

Thus, the abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the

following: prefix + root + lexical suffix+grammatical suffix.

The syntagmatic connections of the morphemes within the model form two

types of hierarchical structure. The first is characterized by the original prefixal

stem (e.g. prefabricated), the second is characterized by the original suffixal stem

(e.g. inheritors). If we use the symbols St for stem, R for root, Pr for prefix, L for

lexical suffix, Gr for grammatical suffix, and, besides, employ three graphical

symbols of hierarchical grouping — braces, brackets, and parentheses, then the

two

morphemic

word-structures

can

be

presented

as

follows:

W1 = {[Pr + (R + L)] +Gr}; W2 = {[(Pr + R) +L] + Gr}

In the morphemic composition of more complicated words these modeltypes form different combinations.

Further insights into the correlation between the formal and functional

aspects of morphemes within the composition of the word may be gained in the

light of the so-called "allo-emic" theory put forward by Descriptive Linguistics

and broadly used in the current linguistic research.5

In accord with this theory, lingual units are described by means of two types

of terms: allo-terms and eme-terms. Eme-terms denote the generalized invariant

units of language characterized by a certain functional status: phonemes,

5

Arnold D. "The English word" M, 1973. p. 299

13

morphemes. Allo-terms denote the concrete manifestations, or variants of the

generalized units dependent on the regular co-location with other elements of

language: allophones, allomorphs. A set of iso-functional allo-units identified in

the text on the basis of their co-occurrence with other lingual units (distribution) is

considered as the corresponding eme-unit with its fixed systemic status.

The allo-emic identification of lingual elements is achieved by means of the

so-called "distributional analysis". The immediate aim of the distributional

analysis is to fix and study the units of language in relation to their textual

environments, i.e. the adjoining elements in the text.

The environment of a unit may be either "right" or "left", e.g.: un-pardonable. In this word the left environment of the root is the negative prefix un-, the

right environment of the root is the qualitative suffix -able. Respectively, the root pardon- is the right environment for the prefix, and the left environment for the

suffix. The distribution of a unit may be defined as the total of all its

environments; in other words, the distribution of a unit is its environment in

generalized terms of classes or categories.

In the distributional analysis on the morphemic level, phonemic distribution

of morphemes and morphemic distribution of morphemes are discriminated. The

study is conducted in two stages.

At the first stage, the analysed text (i.e. the collected lingual materials, or

"corpus") is divided into recurrent segments consisting of phonemes. These

segments

are

called

"morphs",

i.e.

morphemic

units

distributionally

uncharacterized, e.g.: the/boat/s/were/gain/ing/speed.

At the second stage, the environmental features of the morphs are

established

and

the

corresponding

identifications

are

effected.

Three main types of distribution are discriminated in the distributional analysis,

namely, contrastive distribution, non-contrastive distribution, and complementary

distribution.

Contrastive

and

non-contrastive

distributions

concern

identical

environments of different morphs. The morphs are said to be in contrastive

14

distribution if their meanings (functions) are different. Such morphs constitute

different morphemes. Cf. the suffixes -(e)d and -ing in the verb-forms returned,

returning. The morphs are said to be in non-contrastive distribution (or free

alternation) if their meaning (function) is the same. Such morphs constitute "free

alternants", or "free variants" of the same morpheme. Cf. the suffixes -(e)d and -t

in the verb-forms learned, learnt.

As different from the above, complementary distribution concerns different

environments of formally different morphs which are united by the same meaning

(function). If two or more morphs have the same meaning and the difference in

(heir form is explained by different environments, these morphs are said to be in

complementary distribution and considered the allomorphs of the same

morpheme. Cf. the allomorphs of the plural morpheme /-s/, /-z/, /-iz/ which stand

in phonemic complementary distribution; the plural allomorph -en in oxen,

children, which stands in morphemic complementary distribution with the other

allomorphs of the plural morpheme.

As we see, for analytical purposes the notion of complementary distribution

is the most important, because it helps establish the identity of outwardly

altogether different elements of language, in particular, its grammatical elements.

As a result of the application of distributional analysis to the morphemic level,

different types of morphemes have been discriminated which can be called the

"distributional morpheme types". It must be stressed that the distributional

classification of morphemes cannot abolish or in any way depreciate the

traditional morpheme types. Rather, it supplements the traditional classification,

showing some essential features of morphemes on the principles of environmental

study.

We shall survey the distributional morpheme types arranging them in pairs

of immediate correlation.

On the basis of the degree of self-dependence, "free" morphemes and

"bound" morphemes are distinguished. Bound morphemes cannot form words by

themselves, they are identified only as component segmental parts of words. As

15

different from this, free morphemes can build up words by themselves, i.e. can be

used "freely".6

For instance, in the word handful the root hand is a free morpheme, while

the suffix -ful is a bound morpheme.

There are very few productive bound morphemes in the morphological

system of English. Being extremely narrow, the list of them is complicated by the

relations of homonymy. These morphemes are the following:

1) the segments -(e)s [-z, -s, -iz]: the plural of nouns, the possessive case of

nouns, the third person singular present of verbs; the segments -(e)d [-d, -t, -id]:

the past and past participle of verbs; the segments -ing: the gerund and present

participle; the segments -er, -est: the comparative and superlative degrees of

adjectives and adverbs.

The auxiliary word-morphemes of various standings should be interpreted

in this connection as "semi-bound" morphemes, since, being used as separate

elements of speech strings, they form categorial unities with their notional stemwords.

On the basis of formal presentation, "overt" morphemes and "covert"

morphemes are distinguished. Overt morphemes are genuine, explicit morphemes

building up words; the covert morpheme is identified as a contrastive absence of

morpheme expressing a certain function. The notion of covert morpheme

coincides with the notion of zero morpheme in the oppositional description of

grammatical categories (see further).

For instance, the word-form clocks consists of two overt morphemes: one

lexical (root) and one grammatical expressing the plural. The outwardly onemorpheme word-form clock, since it expresses the singular, is also considered as

consisting of two morphemes, i.e. of the overt root and the co\ert (implicit)

grammatical suffix of the singular. The usual symbol for the covert morpheme

employed by linguists is the sign of the empty set:

6

Arnold D. "The English word" M, 1973. p. 299

16

On the basis of segmental relation, "segmental" morphemes and "suprasegmental" morphemes are distinguished. Interpreted as supra-segmental

morphemes in distributional terms are intonation contours, accents, pauses.

The said elements of language, as we have stated elsewhere, should beyond

dispute be considered signemic units of language, since they are functionally

bound. They form the secondary line of speech, accompanying its primary

phonemic line (phonemic complexes). On the other hand, from what has been

stated about the morpheme proper, it is not difficult to see that the morphemic

interpretation of suprasegmental units can hardly stand to reason. Indeed, these

units are functionally connected not with morphemes, but with larger elements of

language:

words,

word-groups,

sentences,

supra-sentential

constructions.

On the basis of grammatical alternation, "additive" morphemes and "replacive"

morphemes are distinguished.

Interpreted as additive morphemes are outer grammatical suffixes, since, as

a rule, they are opposed to the absence of morphemes in grammatical alternation.

Cf. look+ed; small+er, etc. In distinction to these, the root phonemes of

grammatical interchange are considered as replacive morphemes, since they

replace one another in the paradigmatic forms. Cf. dr-i-ve — dr-o-ve — dr-i-ven;

m-a-n — m-e-n; etc.

It should be remembered that the phonemic interchange is utterly

unproductive in English as in all the Indo-European languages. If it were

productive, it might rationally be interpreted as a sort of replacive "infixation"

(correlated with "exfixation" of the additive type). As it stands, however, this type

of grammatical means can be understood as a kind of suppletivity (i.e. partial

suppletivity).

On the basis of linear characteristic, "continuous" (or "linear") morphemes

and "discontinuous" morphemes are distinguished.

By the discontinuous morpheme, opposed to the common, i.e.

uninterruptedly expressed, continuous morpheme, a two-element grammatical unit

is meant which is identified in the analytical grammatical form comprising an

17

auxiliary word and a grammatical suffix7. These two elements, as it were, embed

the notional stem; hence, they are symbolically represented as follows: be ... ing

— for the continuous verb forms (e.g. is going); have ... en — for the perfect verb

forms (e.g. has gone); be ... en — for the passive verb forms (e.g. is taken).

It is easy to see that the notion of morpheme applied to the analytical form of the

word violates the principle of the identification of morpheme as an elementary

meaningful segment: the analytical "framing" consists of two meaningful

segments, i.e. of two different morphemes. On the other hand, the general notion

"discontinuous constituent", "discontinuous unit" is quite rational and can be

helpfully used in linguistic description in its proper place.

1.2. The problem of notional and formal words

In giving a list of parts of speech, we have not so far mentioned the

terms "notional" and "formal". It is time now to turn to this question.

According to the view held by some grammarians,

2

words should be divided

into two categories on the following principle: some words denote things,

actions, and other extralinguistic phenomena (these, then, would be notional

words), whereas other words denote relations and connections between the

notional words, and thus have no direct bearing on anything extralinguistic

(these, then, would be the formal words, or form words). Authors holding this

view define prepositions as words denoting relations between words (or

between parts of a sentence), and conjunctions as words connecting words or

sentences.

However, this view appears to be very shaky. Actually, the so-called

formal words also express something extralinguistic. For instance, prepositions

express relations between things. Cf., e. g., The letter is on the table and The

letter is in the table: two different relations between the two objects, the letter

7

D.Cryslal, The English Language, New York,1998,421p.

18

and the table, are denoted by the prepositions. In a similar way, conjunctions

denote connections between extralinguistic things and phenomena. Thus, in

the sentence The match was postponed because it was raining the conjunction

because denotes the causal connection between two processes, which of course

exists whether we choose to express it by words or not. In the sentence It

was raining but the match took place all the same the conjunction but

expresses a contradiction between two phenomena, the rain and the match,

which exists in reality whether we mention it or not. It follows that the

prepositions on and in, the conjunctions because and but express some relations

and connections existing independently of language, and thus have as close a

connection with the extralinguistic world as any noun or verb. They are, in

so far, no less notional than nouns or verbs.

Now, the term "formal word" would seem to imply that the word thus

denoted has some function in building up a phrase or a sentence. This function

is certainly performed by both prepositions and conjunctions and from this

point of view prepositions and conjunctions should indeed be singled out.

But this definition of a formal word cannot be applied to particles. A

particle does not do anything in the way of connecting words or building a

phrase or a sentence.

There does not therefore seem to be any reason for classing particles with

formal words. If this view is endorsed we shall only have two parts of speech

which are form words, viz. prepositions and conjunctions. 1

It should also be observed that some words belonging to a particular part

of speech may occasionally, or even permanently, perform a function

differing from that which characterises the part of speech as a whole.

Auxiliary verbs are a case in point. In the sentence I have some money left the

verb have performs the function of the predicate, which is the usual function

of a verb in a sentence, In this case, then, the function of the verb have is

precisely the one typical of verbs as a class. However, in the sentence I have

found my briefcase the verb have is an auxiliary: it is a means of forming a

19

certain analytical form of the verb find. It does not by itself perform the

function of a predicate. We need not assume on that account that there are

two verbs have, one notional and the other auxiliary. It is the same verb

have, but its functions in the two sentences are different. If we take the verb

shall, we see that its usual function is that of forming the future tense of

another verb, e. g. I shall know about it to-morrow. Shall is then said to be

an auxiliary verb, and its function differs from that of the verb as a part of

speech, but it is a verb all the same.

After this general survey of parts of speech we will now turn to a

systematic review of each part of speech separately.

1.3. The principle of grouping the words into grammatical classes

The words of language, depending on various formal and semantic features

are divided into grammatically relevant sets or classes. The traditional

grammatical classes of words are called “parts of speech” since the words are

distinguished not only by grammatical, but also by semantico-lexemic properties,

some scholars refer to parts of speech as “lexico-grammatical categories”.

It should be noted that the term “parts of speech” is purely traditional and

conventional, it can not be taken as in any way defining or explanatory. This name

was introduced in the grammatical teaching of Ancient Greece, where the concept

of the sentence was not yet explicity indentified in distinction to the general idea

of speech, and where, consequently, no strict differentiation was drawn between

the word as a vocabulary unit and the word as functional elements of the sentence.

In modern linguistic parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of the

three criteria: a”semantic”, “formal”, and “functional”.

20

The semantic criterion presupposes the evaluation of the generalized

meaning, which is characteristic of all the subsets of words constituting a given

part of speech. This meaning is understood as the “categorical meaning of the

parts of speech”. T he formal criterion provides for the exposition of the specific

inflextional and derivational (word building) features of all the lexemic subsets of

a part of speech. The functional criterion concerns the syntactic role of the words

in the sentences typical of a part of speech. The said three factors of categorical

characterization of words are conventionally referred to as respectively,”

meaning”, “form”, and “function”.

In accord with the described criteria, words on the upper level of

classification are divided into national and functional, which reflects their division

in the earlier grammatical tradition into changeable and unchangeable.

To the national parts of speech of the English language belong noun, the

adjective, the numeral, the pronoun, the verb, the adverb. The features of the noun

within the identification triad “meaning – form - function” are, correspondingly,

the following: 1) the categorical meaning of substance (“thinness”); 2) the

changeable forms of number and case; the specific suffixal forms of derivation

(prefixes in English do not discriminate parts of speech as such); 3) the

substantive functions in the sentence (subject, object, substantive predicative);

prepositional connections; modification by an adjective. The features of the

adjective: 1) the categorical meaning of property (qualitative and relative); 2) the

forms of the degrees comparison (for qualitative adjectives); the specific suffixal

forms of derivation; 3) adjectival functional in the sentence (attribute to a noun,

adjectival predicative). The features of the numeral: 1) the categorial meaning of

number (cardinal and ordinal); 2) the narrow set of simple numerals; the specific

forms of composition for compound numerals; the specific suffixal forms of

derivation for ordinal numerals; 3) the functions of numerical attribute and

numerical substantive. The features of the pronoun: 1) the categorical meaning of

indication (deixis); 2) the narrow sets of various status with the corresponding

21

formal properties of categorical changeability and word – building; 3) the

substantial and adjectival functions for in the sentence (attribute to a noun,

adjectival predicative). The features of the numeral: 1) the categorial meaning of

number (cardinal and ordinal); 2) the narrow set of simple numerals; the specific

forms of composition for compound numerals; the specific suffixal forms of

derivation for ordinal numerals; 3) the functions of numerical attribute and

numerical substantive. The features of the pronoun; 1) the categorial meaning of

indication (deixis); 2) the narrow sets of various status with the corresponding

formal properties of categorial changeability and word – building; 3) the

substantival and adjectival functions for different sets.

The features of the verb; 1) the categorial meaning of process (presented in

the two upper series of forms pespectively, as finite process and non – finite

process) 2) the forms of the verbal categories of person, number, tense, aspect,

voice, mood; the opposition of the finite and non finite forms; 3) the function of

the finite predicate for the finite verb; the mixed verbal – other than verbal

functions for the non finite verb. The features of the adverb: 1) the categorial

meaning of the secondary property, i.e. the property of process or an other

property; 2) the forms of the degrees of comparison for qualitative adverbs; the

specific suffixal forms of derivation; 3) the functions of various of adverbial

modifiers.

We have surveyed the indentifying properties of the national parts of speech

that unite the words of complete nominative meaning characterized by self –

dependent functions in the sentence. Contrasted against the national arts of speech

are words of incomplete nominative meaning and non – self – dependent,

mediatory functions in the sentence, these are functional parts of speech.

On the principle of “generalized form” only unchangeable words are

traditionally treated under the heading of functional parts of speech. As for their

individual forms as such, they are simply presented by the list, since the number

22

of these words is limited, so that they needn’t be identified on any general,

operational scheme. To the basing functional series of words in English belong the

article the preposition, the conjunction, the particle, the modal word, the

intexiection.

The article expresses the specific limitation of the substantive functions.

The preposition expresses the dependencies and interdependencies of

substantive referents. The conjunction expresses connections of phenomena.

The particle unites the functional words of specifying and limiting meaning. To

this series, alongside of other specifying words, should be referred verbal post

positions as functional modifiers of verb, etc. The modal word, occupying in the

sentence a more pronounced or less pronounced detached position, expresses the

attitude of the sparer to the reflected situation and its parts. Here belong the

functional words of probability (probably, perhaps, etc) of qualitative evaluation

(fortunately, unfortunately, luckily, etc), and also of affirmation and negation.

The interjection, occupying a detached position in the sentence, as a signal

of emotions.

Each part of speech after its identification is further subdivided into

subseries in accord with various particular semantico–functional and formal

features of the constituent words. This subdivision is some times called

“subcategorization “of parts of speech.

Thus, nouns are subcategorized into proper and common, animate and

inanimate, countable and uncountable, concrete and abstract, etc. Coin / coins ,

floor / floors , kind / kinds –news , growth ,water , furniture ; stone , grain , must ,

leaf –honesty , love , slavery , darkness.

Verbs are subcategorized into fully predicative and partially predicative,

transitive and intransitive, actional and statal, factive and evaluative etc. walk, put,

23

speak, listen, see, give-live, float, stay, ache, ripen, rain: sail, prepare, shine, blowcan, may, shall, be, become; write, play strike boil, receive, ride-exist, sleep, rest,

thrive, revel, suffex.

Adjectives are subcategorized into qualitative and relative, of contant

feature and temporary feature (the latter are referred to as “statives” and

indentified by some scholars as a separate part of speech under the heading of

“category of state”), factive and evaluative, etc.

Long, red, lovely, noble, comfortable-wooden, rural daily, subterranean,

orthographical; tall, heavy, smooth, mental, native-kind, brave, wonderful, wise,

stupid.

The adverb, the numeral, the pronoun are also subject, to the corresponding

subcategorizations.

We have drawn a general outline of the division of the lexicon into part of

speech classes developed by modern linguistic on the lines of traditional

morphology.

It is known that the distribution of words between different part of speech

may to a certain extent differ with different authors. This fact gives cause to come

linguists for calling in question the rational characteristic of the part of speech

classification as whole, gives theme cause for accusing it of being subjective or

“prescientific” in essence. Such nihilistic criticism, however, should be rejected as

utterly ungrounded. Indeed, considering the part of speech classification on its

merits, one must clearly realize that what is above all important about it is the

fundamental principles of word class identification, and not occasional

enlargementsor diminutions of the established groups, or re – distributions of

individual words due to re – considerations of their subcategorial features. The

very idea of subcategorization as the obligatory second stage of the undertaken

classification testifies to the objective nature of thus kind of analysis.

24

For instance propositions and conjunctions can be combined into one united series

of “connectives”, since the function of both is just to connect national components

of the sentence. In this case, on the second stage of classification, the enlarged

word – class of connectives will be subdivided into two main subclasses namely,

prepositional connectives and conjunctional connectives. Likewise, the articles

can be included as a subset into the more general set of particles-specifics. As is

known, noun and adjectives, as well as description under one common class-term

“names”: originally, in the Ancient Greek grammatical teaching they were not

different cited because they had the some forms of morphological change

(declension). On the other hand, in various descriptions of English grammar such

narrow lexemic sets as the two words yes and no, the pronominal determiners of

nouns, even the one anticipating pronoun it are given a separate class- items

status- though in no way challenging or distarting the functional character of the

treated units.

It should be remembered that modern principles of part of speech

identification have been formulated as a result of painstaking research conducted

on the vast materials of numerous languages: and it is in Soviet linguistic that the

three- criteria characterization of parts of speech has been developed and applied

to practice with the utmost consist ency. The three celebrated names are especially

notable for the elaboration of these criteria, namely, V.V.Vinogradov in

connection with his study of Russian grammar, A.I.Simirnitsky and B.A.Ilyish in

connection with their study of English grammar.

Alongside of the three-criteria principle of dividing the words into

grammatical (lexico-grammatical) classes modern linguistics has developed

another, narrower principle of word-class indentification based on syntactic

featuring of words only.

The fact is, that the three-children principle faces a special difficulty in

determining the part of speech status of such lexemes as have morphological

25

characteristics of national words, by their plating the role of grammatical

mediators in phrases and sentence. Here belong, for equivalents-suppletive fillers,

auxiliary verbs, aspect verbs, intensifying adverbs determiner pronouns. This

difficulty, consisting in the resection of heterogeneous properties in the

established word-classes, can evident is over come by recognizing only one

criterion of the three as decisive. Worthy of note is that in the original Ancient

Greek grammatical teaching which put forward the first outline of the part of

speech theory, the division of words into grammatical classes was also based on

one determining criterion only, namely, on the formal-morphological featuring. It

means that any given word under analysis was turned into a classified lexeme on

the principle of its relation to grammatical change. In conditional of the primary

acquisition of linguistic knowledge, and in connection with the study of a highly

inflexional language this characteristic proved quite efficient.

Still at the present stage of the development of linguistic science, syntactic

characterization of words that has been made possible after the exposition of their

fundamental morphological properties is far more important and universal from

the point of view of the general classification requirements.

This characterization is more important because is shows the distribution of

words between different sets in accord with their functional destination. The role

or morphological, by this presentation is not underrated, rather it is further

clarified from the point of view of exposing connection between the categoria

composition of the word and its sentence forming relevance.

This characterization is more universal, because it is not specially destined

for the inflexional aspect of language and hence is equally applicable to languages

of various morphological types.

26

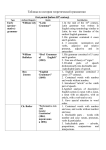

1.3. The syntactic-distributional classification of words

The syntactic- distributional classification of words is based on the study of

their combinability by means of substitution testing. The testing results in

developing the standard model of four main “positions” of notional words in the

English sentence: those of the noun (N), verb(V), adjective(A), adverb(D).

Pronouns are include into the corresponding positional classes as their substitutes.

Words standing outside the “positions” in the sentence are treated as functional

words of various syntactic values.

Here is how CH.Fries presents his scheme of English word classes.

For his materials he chooses tape recorded spontaneous conversation

comprising about 250,000 word intries (50 hours of talk). The words isolated from

this corpus are tested on the three typical sentences (that are isolated from the

records, too) and used as substitution test frames:

A) the concert was good (always);

B) the clerk remembered the tax;

C) the team went there.

The parenthesized positions are optional from the point of view of the

structural completion of sentence.

As a result of successive substitution tests on the cited “frames” the

following lists of positional words (“form words”), or (“parts of speech”) are

established:

Class 1(A) concert, coffee, taste, container difference etc (B) clerk husband,

supervisor, etc; tax, food, coffee, etc.(C)team, husband, woman, etc.

27

Class 2(A) was, seemed, became, etc. (B) remembered, wanted, saw,

suggested, etc. (C) went, came, ran,… lived, worked, etc.

Class 3(A) good, large, necessary, foreign, new empty etc.

Class 4(A) there, here, always, then, sometimes etc (B) clearly, sufficiently,

especially, repeatedly, soon, etc. (C) the beck, out, etc.

All these words can fill in the positions of the frames without affecting their

general structural meaning (such as “thing and its quality ata given time” – their

first frame; actor- action- thing acted upon –characteristic of the action” the

second frame; “action- derection –of – the action”-the third frame). Repeated

interchanges in the substitution of the primarily identified positional (I, e,

notional) words in different collocation determine their morphological

characteristics I, e, characteristics offering, them to various subclasses of the

identified lexemic classes.

Functional words (function words) are exposed in the cited process of

testing as being unable to fill in the position of the frames without destroying their

structural meaning.

These words form limited groups totaling 154units.

The identified groups of functional words can be distributed among the

three main sets. The words of the most set as specifiers of notional words. Here

belong determiners of nouns, modal verbs serving as specifiers of notional verbs,

functional modifiers and intensifiers of adjectives and adverbs. The words of the

seconds set play the role of interpositional elements, determining the relation of

notional words to one another. Here belong prepositions and conjunctions. The

words of the third set refer to the sentence as a whole. Such are question- words

(what, how, etc), inducement words (lets, please, etc) attention- getting words,

28

words of affirmation and negation, sentence introducers (it, there) and some

others.

Comparing the syntactico-distributional classification words with the

traditional part of speech division of words, one cannot but see the similarity of

the general schemes of the twoo: the four absolutely cardinal classes of notional

words (since numerals and pronouns have no positional functions of their own and

serve as pronominal and pro-adjectival elements) the interpretation of functional

words as syntactic mediators and their formal representation by the list.

However, under these unquestionable traits of similarity are distinctly

revealed essential features of difference, the proper evaluation of which allows us

to make some important generalization about the structure of the lexemic system

of language.

29

2.0. CHAPTER II. Contextual-semantics of Functional words in the

English language

2.3 Type of grammatical meaning of parts of speech

used in P.Abraham’s “The path of thunder”

Every language contains thousands upon thousands of lexemes. When

describing them it is possible either to analyses every lexeme separately or to unite

theme into classes with more or less common features. Linguistic make use of

both approaches. A dictionary usually describes individual lexemes, a grammar

book mostly deals with classes of lexemes traditionally called parts of speech.

Though grammarians have been studying parts of speech for over two

thousands years, the criteria used for classifying lexemes are not yet agreed upon.

Hence there is a good deal of subjectivity in defining the classes of lexemes and

we consequently, find different classifications. Still parts of speech are not

altogether an invention of grammarians: what really lies at the bottom of this

division of material reality. The bulk of the class denoting substances is made up

of words denoting material objects such as table, window, milk etc. the vernal of

the class of lexemes meaning processes is constituted by lexemes denoting

concrete actions, such as those writing, reading, speaking, etc.

The lexemes of a part of speech are first of all united by their content, i, e,

by their meaning. Now, this general meaning of a part of speech cannot be

grammatical because the members of one lexeme have different grammatical

meanings: boy’s (singular number, possessive case) boys (plural common case).

Nevertheless, the meaning of a part of speech is closely connected with certain

typical grammatical meanings.

The general meaning of part of speech cannot be lexical. If all the words of

part of speech had the same lexical meaning, they would constitute one lexeme.

30

But the meaning of part of speech is closely connected with the lexical meanings

of its constituent lexemes. It is always an abstraction from those meanings.

Lexemes united by the general lexicon-grammatical meaning of

“substance” are called nouns. Those having the general lexicon-grammatical

meaning of “action” are called verbs, etc., etc

The definition “substance”, “action”, “quality” are conventional. It is easy

to see the notion of “substance” in nouns like water or steel. But a certain stretch

of imagination is necessary to discern the “substance” in nouns like hatred silence,

(a) swim, or the “action” in the verbs belong, resemble, contain and the like.

The general lexicon-grammatical meaning is the intrinsic property of a part

of speech. Connected with it are some properties that find, so to say, outward

expression. Lexicon-grammatical morphemes are once of these properties. The

stems of nouns lexemes often include the morphemes –er, -ist, -ness, -ship, -ment

(worker, Marxist firmness, friendship, management). The stems of verb lexemes

includes the morphemes -ize, -iffy, -be, -en, -en (industrialize, electrify, becloud,

enrich, darken). Adjective stems stems often have the suffixes,-full, -ish, -oust, ive (careful, fearless, boyish, continuous, evasive) . Thus the presence of a certain

lexicon-grammatical morpheme in the stem of a lexeme- often stamps it as

belonging: to a definite part of speech. Many of these morphemes are regularly

used to from lexemes of one class from those all other class. For instance, the

suffix –ness often forms noun stems from adjective stems. Dark-darkness, sweetsweetness, thick-thickness, full-fullness, etc. the absence of the suffix in dark as

contrasted with –ness of darkness looks like a zero morpheme characterizing dark

as on adjective.

Other stem-building elements are of comparatively little significance as

distinctive features of parts of speech. For example: A slow steady movement that

seemed to be independent.

31

Stem structure is of little help too, because there are stems of various kinds

within almost every part of speech: simple (snow, know, now, down), derivative

(belief, believe below, before), compound (get up, at all, one hundred and twenty,

in order to).

Certainly English nouns have many more compound stems than other parts

of speech, and composite stems are most typical of the English verb. But this as a

case for statistics. As a classification criterion it is of little use.

A part of speech is characterized by its grammatical categories manifested

in the opossums and paradigms of its lexemes. Nouns have the categories of

number and case. Verbs possess the categories of tense, voice, mood, etc.

Adjectives have the category of the degrees of comparison. That is why then

paradigms of lexemes belonging to different parts of speech are different. The

paradigms of a verb lexemes is long: write, writes, wrote, shall write, will write,

am writing, is writing, was writing, were writing, etc. The paradigm of a noun

lexeme is much shorter: sister, sisters. The paradigm of an adjective lexeme is still

shorter: cold, colder, coldest. The paradigm of an adverb like always, is the

shortest as the lexeme consists of one word.

It must be borne in mind, however, that not all the lexemes of a part of

speech have the same paradigms.

Cf. 1. Student

book

information.

The first lexeme has opossums of two grammatical categories: number and

case. The second lexeme has only one oppose me – that of number. It has no case

opossum. In other words, it is outside the both categories: it has opossums at all.

We may say that the number oppose me with its opposite grammatical meanings

of “singularity” and “plurality” is neutralized.

32

In nouns like information, bread, milk, etc. owing to their lexical meanings

which can hardly be associated with the notions of “oneness” or “more- than

oneness” (cf. the uncommonness of “two milks” three information etc).

Sometimes only the form of an opossum is neutralized in certain

surroundings.

Ex: Lanny knew that all he had to do was to lower his eyes or look awayany gesture of defeat would have done-and the man would tell him to go.

We may define neutralization as the reduction of an oppose me to one of its

members under certain circumstances. This member may be called the member of

neutralization. Usually it is the unmarked member of oppose me. In number

opossums, for instance, the member of neutralization is mostly the unmarked

“singular”. However, sometimes the marked “plural” because the member of

neutralization, as in the case of trousers, tongs, sweets, etc The category of

number is by no means an exception as regards the neutralization of its opossums.

We may recognize the neutralization of the case opossums in nouns like book,

hand, thought, etc of the category of degrees of comparison in adjectives like deaf,

blind, wooden, etc. of the category of aspect in verbs like to believe, to resemble,

etc.

Ex: A spasm of trembling shot through his body and he became conscious

of the fact that he was breathing hard.

But three are no grounds to speak of the neutralization of the gender oppose

me in the adjective blind (cf.слоеной- слоеная -слоеной) because no adjective

lexemes have gender opossums in English.

The influence of the category of number is obliquely felt even in a case like

milk. The wood milk is closer to the “singular” member it has no positive than to

the “plural” one.

33

Ex: And here I am, Lanny thought, fighting the same battle in the twentieth

century.

Thus, the word milk can be said to have an oblique “singular” meaning. It is

oblique because it is acquired not as a result of direct opposition, but through

association and analogy with words having “plural” opposites. Similarly book can

be said to have an oblique common case meaning by analogy with words like boy,

cook which have an actually meaning of “common case” owing to the opossums

boy-boy’s, cook- cook’s.

Likewise the verbs creeps, comes have an oblique meaning of “active

voice” by analogy with the first members in such opossums as keeps –is kept,

makes-is made.Oblique grammatical meanings can also be regarded as potential

meanings that can be actualized if necessary. Ordinarily the word room, for

instance, has but an oblique meaning of common case with no possessive case

opposite, but Galsworthy uses the room’s atmosphere. We find the same

actualization of a potential number meaning in there was no room for the separate

bitterness.

The actualization of potential “voice” meaning is observed in a sentence

like the bed had not been slept.

Taking into consideration that oblique grammatical meanings unite numbers

of lexemes into more or less homogeneous groups, we may also treat them as

lexicon- grammatical meanings for example, nouns like, milk, water, steel, selfpossession are united by the oblique meaning of singular number into one lexicongrammatical group of uncountable.

Now coming back to the nouns student book information we can say that all

of them have the meanings of singular number and common case. Only in the

noun book the case meaning and in the noun information both of them are oblique

or potential, or lexica-grammatical ones.

34

Another important feature of a part of speech is its combinability i.e. the

ability to form certain combination of words. As stated, we distinguish lexical

grammatical and lexica- grammatical combinability.

When speaking of the combinability of parts of speech, lexica- grammatical

meanings are to be considered first. In this sense combinability is the power of a

lexica-grammatical class of words to form combinations of definite patterns with

words of certain classes irrespective of their lexical or grammatical meanings.

Owing to the lexica-grammatical meanings of nouns (“substance”) and

preposition (“relation (of substances)”) these two parts of speech often go together

in speech. The model to (from, at) school characterizes both nouns and

prepositions as distinct from adverbs which do not usually form combination of

the types “to loudly”, form loudly. The same is true about articles(a book, the

book but not a below the speak), adjectives (pleasant silence but not pleasant

silently), etc.

As already mentioned, a characteristic feature of articles is their unilateral

right-hand combinability with nouns .Unilateral right-hand connection, but with

different classes of words, are also typical of particles (even, john, even yesterday,

even beautiful). Bilateral connection is typical of conjunctions and prepositions.

The connection of nouns and verbs in speech are variable, but right-hand

connections are more numerous with verbs.

Ex: The train hooted shrilly and slowly jogged out of the siding. On its way

to Bloemfontein, and then Johanesburg, and then farther north.

Thus the combinability of a word, its connections in speech help to show to

what part of speech it belongs.

The impossibility of forming combinations with certain classes of lexemes

may serve as valuable negative criteria in the classification of lexemes. Thus the

35

fact that the adjective can form no combinations of the preposition + adjective

pattern or are verbs cannot attach an article help to distinguish them from other

parts of speech.

All this and the desire to avoid, as for as possible the confusion of the two

basic units of grammar the word and the sentence, must necessary reduce the role

of the sentence criterion in defining part of speech. This is why we play it last,

though some linguists. Give it the first place sentence. A noun is mostly used as a

subject or an object, a verb usually functions as a predicate, an adjective- as an

attribute, etc.

Thus a part of speech is a class of lexemes characterized by 1) its lexicagrammatical meaning, 2) its lexica-grammatical morphemes (stem-build

elements), 3) its grammatical categories or its paradigms, 4) its combinability and

5) its functions in a sentence.

All these features distinguish, for instance, the lexeme represented by the

word teacher from that represented by the word teacher and stamp the words of

the first lexeme is nouns, those of the other lexeme as verbs.

But very often or even parts of speech lack some of these features. The

noun lexeme information lacks feature3. The adjective lexeme deaf lacks both

feature 2 and feature 3. So do the adverbs back seldom, very, the prepositions with

of at, etc.

Feature 1, 4 and 5 are the most general properties of parts of speech.

Many linguistics point out the difference between such pars of speech as

say, nouns or verb, on the one hand, and preposition or conjunctions, on the other.

V.V.Vingradov thinks that only noun, the adjective, the pronoun, the

numeral, the verb, the adverb, and the category of site in the Russian language

may be considered parts of speech, as these words “can fulfill naming function or

36

be indicative equivalents of names”8.Besides parts of speech V.V.Vinagradov

distinguishes 4 particles of speech: 1) particles proper, 2)linking particles, 3)

preposition, 4) conjunctions.

Ex: Celia was pretty and a good companion.

One many infer that particles of speech are denied the naming function, to

which we object. There is certainly same difference between the nature of such

words as table and often. One names an object, the other – a relation. But both

“can fulfill the naming function”. Nouns like relation, attitude, verbs like belong,

refer name relation too, but in a always peculiar to these parts of speech.

Preposition and conjunctions name the relation of the word of reality in their own

way.

E. Nita makes no distinction between nouns and prepositions as to their

naming function when he writes that words such as boy, fish, ken, walk, and good,

bad, against and with are signal for various objects, qualities, processes, states and

relationships of natural and cultural phenomena9.

H. Sweet distinguishes full words and empty words. Producing the

sentence: The earth is round, he writes: “we call such words as the and is fromwords because they are words in from only”10

Our opinion is that both the and are words in content as well as in form. The

impossibility of substituting an for the in the sentence above is due to the content,

not the form of an. When replacing is by another link verb (seems, looks) we

change the content of the sentence.

Many authors speak of function words D. Brown, O. Baily11 call “auxiliarly

verbs prepositions and articles” function words. Vzhigadlo, I.Ivanoiva, L lofic12

B.B.BНаградов Русский язык. М. 1997,p.p41-44

B.B.BНаградов Русский язык. М. 1947 p.p4144

10

E.A Nita Morphology. Ann Arbor 1946 p 138

8

9

37

name prepositions conjunctions, particles and articles as functional parts of speech

distinct from notional parts of speech. C. Fries13 points out 4. classes of words

called part of speech and 15 groups of words called functional words.

The demarcation line between function words and all other words is not

words and all other words is not very clear. Now it passes between parts of

speech, now it is down inside a parts of speech.

Alongside of preposition , auxiliary verbs are mentioned. Alongside of

functional parts of speech, grammarians speak of the functional use of certain

classes of words for instance verbs14

The criteria for singling out function words are rather vague. After

enumerating some of separating the words of these 15 groups from the other and

for calling them function words is the fact that in order to res to certain structure

signals one must know these words as items. And again: There are no formal

contrasts by which we can ineptly the words of these lists. They must be

remembered as items15.

The difference between the function words and the other is not so much a

matter of form as of content. The lexical meanings of function words are not so

bright, distinct, tangible as these of other words. If most words of a language are

notional, function words may be called semi – notionally.

As to form, a semi - notional words may coincide with a notional one. Take,

for example the form grows in the two sentences: He grows in the two old. The

first grows expresses an action. What does he do? He grows roses. In the second

case the notion of action is very weak. He grows old can make but a facetious

answer to what does he do? The linking function of grows comes to the fore.

11

Form in Modern English NY,1958

Op cit.., p16

13

The structure of English. London 1961 p 160

14

B.Жигало and others, op cit.., p 89-90

15

E.U.Шендельс “Иностранные языки”

12

38

Grows links a world indicating a person (he) with a word denoting a property of

that person (old). In this function it resembles (and is often inter chainable with) a

few other verbs with faded lexical meanings and clear linking properties (become,

turn, get). The fading of the lexical meaning in grows is connected with changes

in its combinability. As a linking word it acquires obligatory connection, whereas

grows as a notional word has variable combinability. The semi-notional grows

forms connections with adjectives, ad links, with which the notional grows is not

combinable. The fading of the lexical meaning affects the isolatability of words.

Semi-notional words rarely or never became sentences.

A similar distinction can be drown between notional and semi-notional

lexemes within a part of speech and between notional parts of speech.

Preposition, conjunctions, articles and particles may be regarded as seminotional parts of speech when contrasted within the notional parts o f speech.

What unites the semi-notional parts of speech is as follow:

a) Their very general and comparatively weak lexical meanings meaning,

precluding the use of substitutes.

b) Their practically negative isolatability;

c) Their obligatory unilateral (articles, particles) or bilateral (prepositions,

conjunctions) combinability;

d) Their functions of linking (conjunctions, prepositions of specifying

(articles, particles) words.

Naturally, the system of English parts of speech presented above is not the

only some of the above-mentioned properties of parts of speech and neglect the

other we may obtain a different list. Thus if we regard the grammatical categories

of a part of speech as dominant feature and underestimate the lexica- grammatical

meaning, combinability and syntactical function, we are prone to unite adverbs,

39

prepositions, conjunctions, interjection and particles into one class as H. Sweet

and O. Jespersen do H. Sweet finds the following classes of words in Modern

English; nouns, adjectives, numerals, verbs and particles16. O. Jeepers names

substantives adjectives, adverbs, verbs, pronouns and particles17. In both cases the

particles denote the jumble of words of different classes that are united by the

absence of grammatical categories. In we classify notional words in accordance

with their distribution in speech (which is essentially the same as their

combinability) and neglect or underestimate the conclusion that there exist only

four classes of words; nouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs. In modern structural

linguistics these classes are usually denoted by the letters N.A.Vand D

respectively. Since the distribution of John and he is similar in many cases.

Ex; Yes, this was also the end of CAPE TOWN and its bustling and

exciting stream of life.

Both words are thought to belong to the same class N spit of the differences

in their lexica-grammatical meanings and paradigms.

2.1 Grammatical classes of words

The words of language, depending on various formal and semantic

features, are divided into grammatically relevant sets or classes. The traditional

grammatical classes of words are called "parts of speech". Since the word is

distinguished not only by grammatical, but also by semantico-lexemic

properties, some scholars refer to parts of speech as "lexico-grammatical" series

of words, or as "lexico-grammatical categories".

It should be noted that the term "part of speech" is purely traditional and

conventional, it can't be taken as in any way defining or explanatory. This name

was introduced in the grammatical teaching of Ancient Greece, where the

16

17

H. Sweet, op cit.., y, l, p 56.

O. Jespersen Essentials of English Grammar p 16

40

concept of the sentence was not yet explicitly identified in distinction to the

general idea of speech, and where, consequently, no strict differentiation was

drawn between the word as a vocabulary unit and the word as a functional

element of the sentence.

In modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of

the three criteria: "semantic", "formal", and "functional". The semantic criterion

presupposes the evaluation of the generalised meaning, which is characteristic of

all the subsets of words constituting a given part of speech. This meaning is

understood as the "categorial meaning of the part of speech". The formal

criterion provides for the exposition of the specific inflexional and derivational

(word-building) features of all the lexemic subsets of a part of speech. The

functional criterion concerns the syntactic role of words in the sentence typical

of a part of speech. The said three factors of categorial characterisation of words

are conventionally referred to as, respectively, "meaning", "form", and

"function".

In accord with the described criteria, words on the upper level of

classification are divided into notional and functional, which reflects their

division in the earlier grammatical tradition into changeable and unchangeable.

To the notional parts of speech of the English language belong the noun, the

adjective, the numeral, the pronoun, the verb, the adverb.

The features of the noun within the identificational triad "meaning —

form — function" are, correspondingly, the following: 1) the categorial meaning

of substance ("thingness"); 2) the changeable forms of number and case; the

specific suffixal forms of derivation (prefixes in English do not discriminate

parts of speech as such); 3) the substantive functions in the sentence (subject,

object, substantival predicative); prepositional connections; modification by an

adjective.

The features of the adjective: 1) the categorial meaning of property

(qualitative and relative); 2) the forms of the degrees of comparison (for

qualitative adjectives); the specific suffixal forms of derivation; 3) adjectival

41