* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download All material in this program is the exclusive

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

All material in this program is the exclusive

property of the copyright holder. Copying,

transmitting, or reproducing in any form or

by any means without prior written

permission from the copyright holder is

prohibited (Title 17, U.S. Code Sections

501 and 506).

©1992 Chariot Productions

MEDIEVAL TIMES

1000-1450 A.D.

TIME: 30 minutes

INTRODUCTION

Life in the British Isles around the year 1100 was stunningly

different from the high-tech, post-industrial culture of today.

Society was organized according to the principles of feudalism. Economic activity was almost exclusively agricultural and feudal manors tended to be self-sufficient. There

was little trade and few towns.

Medieval Times describes this period by taking a close look

at the castle at Chepstow in South Wales. This beautiful

castle on the Wye river was the first stone fortress erected in

the British Isles following the Norman Conquest in 1066. Four

miles up the river, the video examines the enchanting ruins

of Tintern Abbey, which was founded by the lords of

Chepstow about 900 years ago. By looking at the relationship which evolved between this castle, abbey, and the

manor lands which they controlled, this program recreates

what it must have been like to live during the Middle Ages.

Designed for grades 6-8, the video is divided into two fifteen

minute segments and can be viewed during either one or

two class periods. The first half introduces the subject of

feudalism and goes into detail about castle life. The castle

is looked at both as a home and as a fortress. The second

half of the program examines religious and village life.

-1-

SUGGESTED INSTRUCTIONAL PROCEDURE

A. TEACHER PREPARATION

1. Preview the video and read over the information in

this guide and on the blackline masters.

2. A large map of the United Kingdom will be useful

before and after viewing the program.

3. Duplicate the blackline masters you intend to use.

B. TOPICS PRESENTED IN THE PROGRAM

1.

Background information on Wales, England,

Normandy, and the Norman Conquest.

2.

Description of feudalism and the medieval social

order.

3. Subsection One, The Nobility: Castle Homes. A

look at domestic life in a large medieval castle.

4.

Subsection Two, Knights and Soldiers: Castle

Fortresses. A look at the military side of the

castle and knightly activities.

5.

Subsection Three, The Clergy: A look at cathedrals, churches, monasteries, priests, bishops,

and monks—the role of religion in the Middle

Ages. The effects of the Reformation are presented.

6. Subsection Four, Village Life: A look at the role of

serfs in medieval society and the customary laws

which regulated their lives.

-2-

7. The end of the Middle Ages and the transition

into the Renaissance.

B. STUDENT OBJECTIVES

After viewing this program and participating in the

lesson activities, students should be able to...

Describe the nature of Feudalism as it existed

among the four basic strata of medieval society:

the nobility, the military, the religious, and the

laboring classes.

Discover the intricate relationships that developed among specific medieval institutions over a

period of many centuries by "visiting" the actual

castles, monasteries, and villages in one small

region of Southern Wales.

Experience what it feels like to wander through

ruined medieval buildings while learning the

purposes served by their long-abandoned rooms.

Describe many of the major historical events in

the United Kingdom from the Norman Conquest

up to the Reformation.

C. INTRODUCING THE LESSON

1. Introduce the program with a brief description of its

content: a look at the feudal lifestyles of four

medieval social classes—the nobility, the military,

the religious, the laborers. Tell the students that

the castles and other ancient buildings in this

program were all intimately interrelated during the

medieval period.

-3-

2. Ask a few thought-provoking questions,

example:

labeled parts with the class and imagine what it

might be like to live in such a castle. Have the

students look up the unfamiliar words. You might

want to use this drawing both before and after

viewing the video, or the class may want to view

the video again to look for some of the places

illustrated.

For

a. How was life different in the Middle Ages than

it is today? How might it be similar?

b.

3.

What do you imagine were the principle

factors which shaped the lives of medieval

people? What factors shape our lives today?

Distribute Blackline Sheets 1 and 2, Vocabulary. Have the students read over the definitions

so they will be familiar with the words and phrases

as they are used in the video.

D. PRESENT THE VIDEO-TIME: Part 1-15 min.

Part 2-15 min.

4. In lieu of a quiz, have the students write a story or a

report on Medieval Times using the words on

Sheets 1 and 2, Vocabulary.

F. EXTENDED ACTIVITIES

1. Discuss the principles of feudalism and compare

them to a modern democracy. This subject could

also serve as a topic for a term paper.

2.

Discuss the medieval roots of our twentieth

century American legal system. Where does the

notion of the "court" system come from? What

are the roots of "common law"? This subject

provides an excellent topic for term papers.

3.

Discuss the medieval view of the world and its

relationship to popular religious beliefs. In what

way has the growth of science altered the way

we see the world? Do you think the sense of all

pervasive magic died as the influence of religion

began to decline? This subject also provides an

excellent topic for term papers.

E. FOLLOW-UP ACTIVITIES

1. Distribute Blackline Sheet 3, Map of Europe.

The students will need colored pencils or crayons to complete this exercise. You may wish to

add other locations for them to locate. (While

Chepstow Castle did not exist in A.D. 1000, this

map is representative of the area at the time it

was built.)

2.

Distribute Blackline Sheet 4, Word Find. Tell

the class that the words appear vertically, horizontally, and at a slant. Some words in the

vertical position appear backwards.

4. How did the feudal system develop in Europe?

3. Distribute Blackline Sheet 5, A Norman Castle.

This labeled drawing can be projected to trace

into a larger bulletin board display. Discuss the

-4-

-5-

G. ANSWER KEY

Blackllne Masters 1 and 2, VOCABULARY

Blackllne Master 4, WORD FIND

Words are defined.

Blackllne Master 3, MAP OF EUROPE

Blackline Master 5, A NORMAN CASTLE

A labeled line drawing of a typical Norman castle, ca.

1200.

-6-

-7-

SCRIPT OF VIDEO NARRATION

CASTLES AND CATHEDRALS

LIFE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

1000-1450

When you hear of "the Middle Ages," what do you

imagine?...a time long ago when lords and ladies lived in

fantastic castles...and knights in armor roamed the

countryside...when enormous cathedrals towered over the

villages...and peasants worked in the fields?

It seems like a fairytale world to us now, but it really existed.

And, although the voices of the people who lived in those

times are now silent, the buildings and works of art they left

behind can tell a fascinating story of what life was like in the

Middle Ages.

Our story takes place here in the fertile farmlands near the

west coast of England. For centuries these lands were

home to a Celtic-speaking people called the Welsh who

lived in the kingdom of Wales.

The Welsh fought hard to protect their lands—first from the

Romans and later from the Anglo-Saxons.

Then, when England was conquered by William, the Duke of

Normandy, at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the Welsh

faced a new enemy as some of the Welsh homelands were

divided among the Norman invaders.

The Normans brought with them the medieval culture and

architecture of their French homeland and soon the countryside rang out with the sounds of the mason's chisel as

great stone castles, abbeys, and cathedrals were constructed, some taking hundreds of years to complete.

-9-

The first great fortress to be built following the Norman

Conquest was Chepstow Castle. From its protected vantage

point high on the cliffs above the river Wye, the lords and

ladies could keep an eye on everyone who travelled the

coastal road between England and Wales, and they could

defend themselves against attack by the enemy Welsh.

Smaller landholders formed the center of the social pyramid. Quite often these small landholders were knights in

the service of earls and other nobles.

A village soon grew up under the protection of the castle,

the villagers working in the lord's fields or as servants in the

castle.

At the pyramid's base were huge masses of serfs, the

landless unpaid laborers who dwelt in villages and worked

the land for a share of the crops they raised.

Then, 65 years after construction began on Chepstow

Castle, the lord brought monks over from Normandy to

establish a great church at Tintern, five miles up the Wye

River. At the same time, a Norman knight began to build his

own smaller castle on the lands of Penhow, eight miles west

of Chepstow.

PART ONE: CASTLE LIFE

Together, Chepstow Castle, the surrounding village, Tintern Abbey, and the knight's castle of Penhow formed a

complete medieval society based on the principles of

feudalism, which governed how people lived and worked

and what they believed. Everyone's place in this society

was strictly defined—lords and ladies, servants and craftsmen, knights and monks—all had their roles in feudal

society.

FEUDALISM: THE MEDIEVAL SOCIAL ORDER

Feudalism was based on the service of a vassal to his lord

in exchange for protection and the right to live on his land.

The feudal nobility formed the top of a social pyramid

whose tip was composed of royalty—the kings, queens,

princes, and princesses who ruled over entire countries.

Lower in rank were the dukes, earls, barons, and other

lesser nobles who controlled vast regions within the king's

-10-

domain. In exchange they provided him with armies and

treasure.

The castles of 900 years ago were not just fortresses. They

were also the homes of noblemen and their families. A

great castle was like a small self-contained town. Inside its

walls you could find almost everything you wanted.

It took lots of work and many people to keep the castle

running smoothly. One large English castle records employing 300 full-time servants.

Like most medieval fortresses, Chepstow Castle was

constructed in stages over many centuries. Chepstow

began as a single great stone tower. Life in this tower was

difficult, but these Norman invaders were a tough and

determined group. Their main concern was just to survive in

the midst of a very hostile environment.

It was cold inside this tower, which was built without a

fireplace. The only warmth was provided by portable

braziers filled with burning coals.

Most of the lord's day-to-day, social, administrative, and

military duties were performed inside the tower within this

great hall. Meals were served here, and each day the

servants made up dining tables by placing thick boards on

wooden trestles.

-11-

The early Normans were not used to having much privacy for

at night the tables were simply put away and the lord, his

family, guests, and dogs curled up on the floor and went to

sleep.

Starting in 1270, as war raged between the kingdoms of

Wales and England, the lord of Chepstow Castle decided to

make his home more comfortable and construction began on

a new hall, kitchens, pantries, cellars, and living quarters.

Because some of these rooms are in ruins today, we can

only imagine how they must have looked over seven

hundred years ago, but we can get some impression of their

appearance by looking at rooms serving similar purposes at

nearby Penhow Castle.

Here the dining table stands in the castle's great hall

beneath a ceiling supported by heavy oak beams, overlooked by a minstrels' gallery where musicians performed

during many lavish banquets.

The nobles ate two hot meals a day. They feasted on wild

game and a variety of strong spicy foods.

At Chepstow Castle food was prepared in a large kitchen

building serparate from the hall, for the kitchen was a

smokey place where a big open fire always blazed, meat

roasted, kettles boiled, and endless loaves of bread were

baked in ovens along the kitchen wall.

Because hundreds of people lived in large castles, quite a

few rooms were dedicated to food preparation and storage.

Beneath the great dining hall at Chepstow are cellars where

food was stored after being hoisted up from boats in the

river below.

the butler kept track of the castle account books. Also

beneath the hall is a pantry for final food preparation and

stone cupboards where knives and table linens were kept.

Across the courtyard from the kitchens and dining hall, a

new tower was constructed to shelter the late 13th century

lords of Chepstow Castle. It is a massive structure when

seen from outside the curtain walls, showing clearly the

huge pyramids of stone employed to protect it from attack by

the battering ram.

To reach the bedchambers within the tower, the noble

lords, ladies, and their children climbed a steep winding

staircase. Their bedchambers may once have resembled

this room at Penhow Castle with a large bed, a smaller

child's bed, and a chest for clothing. In a room just like this a

nobleman could sit in a window seat and survey his domain

in safety.

On cold winter days, many lords conducted castle business

from their bedchambers, enjoying the warmth of the fireplace in an otherwise cold and drafty building.

The nobility loved to show off their riches, not only by

constructing enormous castles, but also by wearing the

elegant clothing which set them apart from the common

people.

In the late medieval era, the nobles passed "sumptuary

laws" which forbid even the wealthiest commoners from

wearing lavish clothing. The nobles reserved the most

ornate styles for their class alone.

Dressed in their finery, lords and ladies spent a good deal of

time in the pursuit of pleasure: attending mock battles,

feasting, and hunting rabbits or other small game with

falcons especially trained for this purpose.

Nearby is a buttery where wine and beer were stored and

-12-

-13-

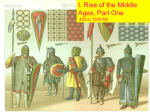

KNIGHTS, SOLDIERS, SQUIRES, AND PAGES

Noblemen were not the only people who owned castles. The

lord of Chepstow granted the lands of Penhow Castle to one

of his loyal Norman knights for a "knight's fee," that is, in

exchange for keeping the Welsh subdued, providing a

monthly quota of men to serve at Chepstow Castle, and

supplying one mounted soldier in times of war.

Most castles were surrounded by water-filled moats. In

times of war the drawbridge was raised, a powerful grate

was dropped, and the castle doors were locked behind both

of them. Even if attackers could get close enough to chop

through the doors, they were still vulnerable to arrows,

rocks, and boiling oil streaming through "murder holes"

above the castle's entrance.

A knight's position in society required him to be both a

military man and landowner. As a landowner it was his duty

to oversee the smooth operation of his farms and village.

Captured attackers met horrible fates. They were locked up

in cold windowless dungeons and often underwent

gruesome ordeals.

Yet knights, like all other wealthy members of medieval

society, were forced to raise their families behind thick

castle walls for these were dangerous times.

In addition to the safety provided by the castle itself, armor

offered further protection to knights in battle.

In the Middle Ages the nobility made the major military

decisions, ordering knights and soldiers into battle. Some

were even sent on crusades traveling thousands of miles to

fight the Moslems who occupied the holy sites of Christianity.

Knights were distinguished from common soldiers because

they fought on horseback.

It cost a great deal of money to be a knight: a warhorse,

shield, and armor cost as much as a poor farm worker could

earn in 100 years.

In the field of battle a knight on horseback had the advantage over the foot soldier. He was faster, had better armor,

and superior training.

But even fully armored knights could not withstand a steady

shower of arrows unleashed from behind castle walls. From

high above, archers shot down at attackers through the

gaps in the tower walls, and they could move safely along

the wall walks to reach special arrow slits.

-14-

In the early Middle Ages armor constructed of many tiny

loops of metal called chain mail protected men from arrows

shot from longbows. However, with the invention of the

powerful crossbow, armorers abandoned chain mail for

stronger suits made of metal plates. These heavy outfits

provided excellent protection but were extremely hot and

difficult to move about in, and a knight who was knocked off

his horse in battle had little hope of getting up without

assistance.

From the 12th to the 14th centuries, mock battles or

tournaments were a favorite form of entertainment at

castles. These grand spectacles were an excellent way for

knights to practice for real warfare, and, although tournaments were played with blunted weapons, they could still

be very dangerous games. When knights fought in teams,

the event was called a melee, but, if knights competed one

on one, it was called a joust.

In medieval times every upper class family had a coat of

arms. These were proudly displayed at tournaments on

shields and banners. Coats of arms contained important

symbols reflecting family heritage. Even the clergy pos-15-

sessed coats of arms like these of the bishops of Gloucester.

Training for knighthood began at the age of eight when a

boy from a noble family became a page. This first stage of

his education focused on horsemanship, chess, falconry,

reading, writing, and good manners.

The page became a squire as he entered his teens, serving

at his master's side in battle. When his training was

completed, an elaborate ritual was performed, and, with the

tap of a sword, the squire was transformed into a young

knight.

Knighthood was a source of tremendous pride and power,

but sometimes this power was abused, and members of the

lower classes were badly mistreated. Yet knighthood often

brought great glory. And to this day every large European

church holds the tombs of these ancient warriors. Clad in

armor, even in death, they act as silent reminders of a long

vanished age.

PART 2 THE CLERGY:

RELIGIOUS LIFE

Religion played a very important role in the lives of people

during the Middle Ages. While not everyone was a sincere

believer, the power of the Roman Catholic Church over

people's lives far exceeded that of any worldly king.

Nearly every village had a small church whose priest was

just as poor as the members of his flock. The priest said

daily masses and performed the holy sacraments which

marked the passing of each stage of life.

The Church strictly regulated people's behavior in medieval

times. Rich and poor alike were taught the consequences

of their deeds. The vivid artwork of the churches

-16-

offered glimpses into the unbearable suffering of hell and

the unimaginable bliss of heaven.

The Middle Ages was a time of magic and mystery, but most

people were illiterate. The priest was often the only person

In a village who could read and write. The Church was the

only institution of the age which supported education. The

two oldest English universities— Cambridge and Oxford—

were both founded by the Church over eight centuries ago.

In the Middle Ages every family was expected to donate ten

percent of their income to the Church. These tithes, as they

were called, were collected from the villagers at harvest

time when one-tenth of their crops were taken to Chruchowned tithe barns like this one before being sold.

As a result of this practice, the Church became very

wealthy. Enormous ornate churches called cathedrals were

built in most major towns to serve as centers of church

administration. One town competed with another to see

which could create the most lavish building. These magnificent structures required the labor of hundreds of men and

many centuries to complete.

Cathedrals were the homes of high ranking priests of the

Church called bishops. These men controlled the Church's

wealth and oversaw the activities of hundreds of parish

priests. Bishops were social equals to noblemen and, like

them, lived in splendid palaces. Although there were many

good bishops, some were corrupted by the wealth they

controlled. Bishops sometimes became objects of scorn to

the impoverished villagers who saw their hard-earned tithes

wasted on decorations instead of being used to save souls.

The Protestant Reformation, which began in Europe near

the end of the fifteenth century, started as a reaction to the

worldliness of the Church.

-17-

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Church had become

increasingly involved in struggles for power with the nobility.

As a result, in the 1530s England's King Henry the Eighth

decreed himself leader of the Church of England and

ordered all the monasteries in his realm to be closed forever.

Their treasures became the property of the king, and their

leaden roofs were sold for scrap.

This monastery, called Tintern Abbey, lies only five miles

up the Wye River from Chepstow Castle. The foundation

stones of this abbey were laid down only sixty-five years

after the Norman Conquest. The money for this enormous

project was provided by the lord of Chepstow Castle

himself. Such extravagance was not unusual in the Middle

Ages, for these acts of piety were thought to spiritually

benefit the donors who hoped that gifts to the Church might

help clear their ways on the path to heaven.

While cathedrals were town-based administrative centers

of the Church, monasteries were rural centers of intense

religious practice where communities of either monks or

nuns lived in isolation, cut off from all worldly influences.

On this spot, for over five hundred years, untold numbers of

men spent their entire adult lives in quiet seclusion following

strict rules designed to bring them closer to God.

Like Chepstow Castle, Tintern Abbey depended on the

produce of its lands for most of its income. And, although

the monks performed some of the labor in the fields, most

was carried out by the lay brothers—poor, illiterate men

who arrived in surprising numbers at the monastery gates

seeking food and shelter. The fully trained monks, called

choir monks, shared the monastery with the lay brothers but

occupied separate areas for worship, sleeping, and eating.

Most of Tintern Abbey lies in total ruin, but a nearby

cathedral, which was once a monastery, still retains impor-18-

tant structures lost at Tintern.

All monasteries had cloisters, which are covered walkways

surrounding a central garden that connect most of the

monastery buildings. Centuries ago they were the site of a

lot of daily activity. Here monks read the scriptures as they

walked along, studied in compartments along the outer

wall, listened to the abbot teach, and washed their hands in

the lavatorium before eating their two simple daily meals.

Near the lavatorium were dining halls, dormitories, and the

warming house, which was the only place {other than the

kitchen and hospital) where a fire was allowed to burn.

Here the monks could restore the circulation to their bodies

after hours in the freezing church.

Choir monks offered their entire lives as a sacrifice to God.

Their day began at 2 A.M. when they formed a candlelit

procession entering the church by special stairs leading

from their dormitories. By the time the first rays of light

passed through the stained glass windows, many hours of

the day had already been spent in darkness.

Throughout the day, hours of worship alternated with

periods of study until finally, after sunset, the last prayers

were said and the monks were free to return to their beds to

sleep.

SERFS: VILLAGE LIFE

While the lives led by the monks of Tintern Abbey were hard

and tiring, so were those of the serfs who farmed the fields.

There were more serfs one thousand years ago than all the

other social classes combined. The serfs owned no land,

instead they farmed long strips within great fields belonging

to their masters. They were allowed to keep most of their

produce. The Church, however, took its share in tithes, and

-19-

the landlord required a certain number of days labor each

week in his fields.

The serfs dwelt in small villages, which often grew up within

sight of a castle. In times of danger the serfs could seek

safety behind the castle walls. Because the lord of the

castle provided the serfs both with protection and with the

land to work, the serfs were said to be "bound to the land." If

the land was sold, the serfs were sold with it.

Like all large medieval land holdings, those belonging to

Chepstow Castle and Tintern Abbey were subdivided into

smaller units called manors. A typical manor consisted of a

fortified house, a church, a village, and a few farms. The

"lord of the manor" could be a knight, son, brother, or uncle

of the lord of the castle.

Manor villages were separated by many miles of rough

road through dark forests. News travelled slowly and, as a

result, the villagers world seemed small. Most serfs rarely

travelled beyond the borders of their manor lands. Villages

were self-sufficient, producing everything they needed from

food to clothing to furniture.

Village women in the Middle Ages helped in the fields, but,

because they were often pregnant or looking after children,

their work focused on life at home. Women sewed clothing,

cooked, mended, tended the fire, and preserved food,

keeping their families warm, happy, and properly fed.

The main work of the village men was raising grain. It is not

surprising, therefore, that most manors possessed their

own mills for making flour.

The laws governing the milling of grain are typical of the way

a serf's life was regulated by the customs of the manor. A

serf was required to pay to have his grain turned into flour at

the lord's mill. Serfs caught grinding grain with their own

hand mills were fined and their mills were destroyed.

-20-

Serfs had to take their flour to the baker to be made into

bread. Only one person was allowed to perform this skilled

task here in the village bake house. The baker, like other

craftsmen, was a freeman and was not bound to the land

like the lowly serfs.

Many other laws shaped the life of a medieval peasant.

Hunting in the lord's forests was forbidden, for the lord

reserved the wild game for his family and friends alone.

Serfs were not even allowed to hunt the doves which flew

throughout their villages. Doves were considered the lord's

property, and every manor house had a nearby dovecote

where these birds were raised for meat, eggs, and the

fertilizer they created. It is easy to see why the often hungry

serfs resorted to poaching game, the most common offense in the Middle Ages.

Even rules governing the gathering of wood were very

strict. Not one stick could be gathered before paying the

lord his annual "wood penny," and even then only dead and

fallen limbs could be taken.

The lord of the manor also regulated the use of grazing land.

Common land, the village green, was set aside for use by

the serfs' animals.

The lord and the Church even managed to increase their

wealth at the serfs' expense upon his death. At this time his

heirs were required to give the lord his best animal as a

death tax and the Church took his second best animal as a

death gift called a mortuary.

Life on the medieval manor was not easy, but most serfs did

not question their roles in society. There were pleasant

times like Christmas when they received gifts from the lord,

and they were given feasts at harvest time.

-21-

Medieval villagers, although very poor, also found pleasure in

their families and friends. The Church taught that poverty

itself was noble, and no doubt most of them believed that

the suffering they endured on earth would earn them a

special place in heaven.

By the mid 1500s a new interest in science and art began to

grow as the Age of Rebirth or Renaissance dawned, and

night fell forever on the medieval world.

CONCLUSION: THE END OF THE MIDDLE AGES

By the fifteenth century the sun had begun to set on the

Middle Ages and its feudal way of life.

Feudalism had arisen in response to warfare which existed

between many small kingdoms, but, as the ever-growing

web of feudal ties between nobles and their subjects began

to link every aspect of medieval life, warfare gradually

lessened, and society stabilized.

People became increasingly bound to one another in ways

which made war a less desirable way of solving problems

than it had been in the past, and rule by law made peace a

more realistic possibility.

Throughout the land nobles abandoned their castles or

converted them into elegant palaces, and the Protestant

Reformation altered forever the face of the Church in

England.

More than one-quarter of the population fell to the Black

Plague creating a severe labor shortage. Now serfs could

demand, and get, better living conditions until finally serfdom disappeared in England altogether.

As cities began to grow, trade flourished ending the isolation so characteristic of the feudal world.

The vision of the people began to expand from the boundries of their tiny villages to encompass the entire world as

explorers set sail on voyages of discovery.

-22-

-23-

I

Name______________________

MEDIEVAL TIMES

VOCABULARY (Page 1)

Anglo-Saxons: Germanic people who lived in England in the centuries before the Norman Conquest.

Aristocracy: A privileged minority, usually based on inherited wealth and high social position.

Battle of Hastings: The decisive battle, in 1066, of the Norman invasion near the southern English town of

Hastings.

Bishop: A clergyman of noble rank, higher than a priest, in charge of the administration of a diocese.

Cathedral: The main church for a district or diocese which served as the seat of a bishop.

Celtic: Refers to a language variety spoken in Wales, Brittany, Ireland, and Scotland. Also refers to the

ancient peoples called the Celts.

Chivalry: Knightly qualities such as valor, fairness, courtesy, respect for women, and protection of the poor.

Cloisters: A monastic place, but especially the arched and covered walkways around a central garden that link

monastery buildings.

Coat of Arms: A shield marked with the insignia or designs of a particular family or group

Dark Ages: The period of European history from the fall of the Roman Empire to about the end of the tenth

century. The first part of the Middle Ages, characterized by barbarian invasions, widespread ignorance, and

lack of progress.

Diocese: A church district under a bishop's authority.

Falconry: Hunting with trained falcons.

Feudalism: The economic, political, and social organization of medieval Europe in which land held by

vassals in exchange for military or other services was worked by serfs who were bound to the land.

Joust: A combat or mock combat with lances between two knights or soldiers.

Knights: A military servant often holding land on the condition that he serve his master as a mounted man at

arms.

Medieval Times

©1992 Chariot

2

Name______________________

MEDIEVAL TIMES

VOCABULARY (Page 2)

A Manor: A district controlled by a feudal lord, usually consisting of a few farms, a village, a church, and a

manor house.

Medieval Era: The period of the Middle Ages.

Melee: A fight or mock fight between groups of knights or soldiers.

Middle Ages: The period of history between the fall of the Roman Empire, around 500 A.D., to the birth of the

Rennaisance, about 1450 A.D. The period from 500 A.D. and 1000 A.D. is called the Dark Ages so that the

period 1000-1450 A.D. is commonly called the Late Middle Ages or High Middle Ages.

Monk: A man who lives alone or with a religious order which is separated from normal worldly activities and who

lives according to strict rules under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

The Norman Conquest: The defeat of England by French Norman invaders under Duke William of

Normandy.

Normandy: A dukedom of France located in the northwest part of that country. Named for the vikings or

northmen who settled there in the 900s.

Page: A boy attendant to a knight who was in training for the knighthood.

The Reformation: The movement which sought to reform certain corrupt practices of the Catholic

Church and which led to Protestantism.

The Renaissance: The great rebirth of art, literature, and learning in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries which

marked the transition from the medieval to modern periods of European history.

Serf: A person in feudal servitude, bound to his master's land and transferred with it when it passed to a new

owner.

Sumptuary Laws: Laws restricting the use of extravagant clothing and food.

Tithing: One-tenth of annual produce or money paid as a tax to support the church and clergy.

Wales: A celtic-speaking region in the southwest portion of the United Kingdom which was a separate

kingdom up until the end of the thirteenth century.

Medieval Times

©1992 Chariot