* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1. Consumer Theory (Cont.) 1.5- Consumer Choice 1.6

Survey

Document related concepts

Marginalism wikipedia , lookup

Rebound effect (conservation) wikipedia , lookup

History of macroeconomic thought wikipedia , lookup

Brander–Spencer model wikipedia , lookup

Yield curve wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Laffer curve wikipedia , lookup

Kuznets curve wikipedia , lookup

Economic calculation problem wikipedia , lookup

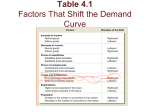

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Macroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Economic equilibrium wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

0DVWHULQ(QJLQHHULQJ3ROLF\DQG7HFKQRORJ\ 0DQDJHPHQW 0,&52(&2120,&6 /HFWXUH 1. Consumer Theory (Cont.) 1.5- Consumer Choice 1.6- Demand 1.7- Market Demand 5HDGLQJV • Mandatory: Varian, H., Intermediate Microeconomics, 5th edition, Norton, 1999. Chapters 5-6, 15. 1 &21680(57+(25<&RQW &RQVXPHU&KRLFH After going through the consumer’s budget constraints and preferences, we now address the issue of optimal choice, which entails answering the question of how do consumers choose the best bundle of goods they can afford. 7KH2SWLPDO%XQGOH • The answer is simple! The consumer chooses the bundle within the budget set that is on the indifference curve that provides the highest level of utility. • If we keep the assumption of monotonic and convex preferences, we can restrict our attention to the bundles that lie RQ the budget line, because anywhere else in the budget set is not consistent with optimising consumer behaviour. • Thus, to find the RSWLPDO consumption bundle, denoted by 0 * [ 1 5 , [2* , we just start from one extreme of the budget line and move along until the highest indifference curve is found. 2 X2 Optimal Choice X1 • The bundle 0 * [ 1 5 , [2* is optimal because all better bundles lie beyond the budget line, which means that the consumer cannot afford them. • Notice that at the optimal bundle the indifference curve is WDQJHQW to the budget line. That must be the case, because if budget line crossed the indifference curve at the optimum, it would mean that there would be another point in the budget line that would be preferred and so that bundle would not be optimal. • 5HVXOW : For well-behaved (monotonic and convex) preferences, the optimal consumption bundle is found at 3 the point where the budget line is tangent to the indifference curve. • For well-behaved preferences, WDQJHQF\LVDQHFHVVDU\DQG VXIILFLHQW FRQGLWLRQ IRU RSWLPDOLW\ . Moreover, for strictly convex preferences, there is only one point of tangency, meaning that the optimal bundle is unique. • This result implies that the slopes of the two lines must be equal at 0 * [ 1 5 , [2* . This, in turn, means that: 056 2SSRUWXQLW\FRVW , or 056 =− S 1 S 2 • The economic interpretation of this implication is that, at the optimum, the consumer substitutes one good for another at rate that is identical to the market’s. Suppose that 056 = −1 2 and the S 1 S 2 = 1. This means that the consumer is willing to trade two units of good 1 for one unit of good 2, whereas in the market the two goods are traded in a one-to-one basis. Therefore, the consumer would be willing to save on good 1 to buy more of good 2, and so the original situation could not be optimal. 4 ([FHSWLRQVWRWKH2SWLPDOLW\5XOH • In general, the rule may be broken whenever preferences are not well-behaved. If we keep the assumption of monotonic preferences all along, then the rule is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for optimality. • There many exceptions to the rule, but two in particular are worth mentioning: - .LQN\ 3UHIHUHQFHV : In this case the optimum occurs at point where the indifference curve does not have a tangent. ),* - &RUQHU 6ROXWLRQ : Whenever the slope of the indifference curve never equals (within the relevant quadrant) that of the budget line, then the optimal bundle is found on one of the axis, i.e. the consumption of one of the goods is zero. In this case, we have a FRUQHU solution, as opposed to an LQWHULRU solution, to the consumer’s problem. 5 ([DPSOHV • 3HUIHFW VXEVWLWXWHV : In this case the slope of the indifference curve is constant, which means that only by chance do we get an interior solution: [ 1 %K =& K' P S 1 DQ\ QXPEHU EHWZHHQ 0 < S = 1 S 1 0 DQG P S 1 S 1 > S 2 S 2 S 2 6 • &REE'RXJODV 3UHIHUHQFHV : In this case, what would be the optimal bundle, given prices and income? To answer that we will maximise the utility function given the budget constraint, by the /DJUDQJH¶VPHWKRG. To do that, we will first set up the /DJUDQJHDQIXQFWLRQ: / =X 0 [ [ 1 2 , 5 − λ0 S [ 1 1 + S [ 2 2 −P 5 and differentiate to get the 3 first-order conditions: %K ∂ = ∂ KK ∂ &K∂ = KK ∂ = ' ∂λ / [ 1 / [ D D[ 1 −1 D [ E E[ [ 1 2 E 2 −1 − λS1 = 0 − λS2 = 0 2 / S [ 1 1 + S2 [2 − P = 0 7 Solving this system in order to 0 [ [ 1 2 , 5 we get the optimal bundle as: * [ 1 = * 2 = [ D D D P +E S 1 E P +E S 2 $SSOLFDWLRQ&KRRVLQJ7D[HV Now that we know something about how the consumer carries out his/her optimal choices, we can try to compare the effects of a TXDQWLW\ WD[ and an LQFRPH WD[ that raises the same amount of revenue and find out which one is less harmful. The government imposition of a quantity tax on, say good 1, will probably affect the optimal consumer’s choice. However, the new optimal bundle 0 * [ 1 5 , [2* still must satisfy the budget line, so that the following holds: 0 S 1 +W 5 * [ 1 + S2 [2* = P It turns out that the revenue generated by the tax is given by: 5 * = W[1* The imposition of an income (lump-sum) tax that would raise 5 * = W[1* would imply the following budget line: 8 S [ 1 1 + S2 [2 = P − W[1* This means that the budget line would maintain the slope but would shift inwards in a parallel fashion. Moreover, it would 0 pass through the point * [ 1 5 , [2* , since this bundle must be affordable. However, at this point the 056 =− 0 S 1 +W 5 S 2 , meaning that the budget line associated with the income tax crosses the indifference curve at 0 * [ 1 , [2* 5 and so 0 * [ 1 , [2* 5 cannot be optimal, since there is a bundle positioned at a higher indifference curve that is still affordable. 9 It turns out that the income tax is less harmful than the quantity tax as it raises the same amount of revenue but leaves the consumer at a higher indifference curve. 10 'HPDQG As we have seen, the optimal demand for [ DQG [ 1 2 , depend on the prices and income. So we use the following notation to denote the GHPDQGIXQFWLRQ of each of the goods: [ 1 = [1 [ = [2 2 0 0 S 1 , S2 , P S 1 5 5 , S2 , P The aim of this section is to analyse how the optimal consumer’s choice changes as income and price change. 1RUPDODQG,QIHULRU*RRGV • 1RUPDO *RRGV : When the optimal consumption of a particular good increases (decreases) as income rises (falls), we say that this good is QRUPDO: ∂[1 >0 ∂P • ,QIHULRU *RRG : If, conversely the consumption of one good decreases (increases) as income rises (falls), then we are in the presence of an LQIHULRU good. Example: As the income of a young professional increases he might consume less sandwiches (and more restaurant meals). 11 ,QFRPH2IIHU&XUYHVDQG(QJHO&XUYHV We have seen that increasing the income leads to an outward shift in the budget line that generates new optimal bundles. • ,QFRPH 2IIHU &XUYH : This curve corresponds to the line that connects the demanded bundles that result from successive outward shifts of the budget line. • (QJHO &XUYH : This curve corresponds to the graph of the quantity demanded of one good as a function of income, with prices held constant. 12 ([DPSOHV : Perfect substitutes, perfect complements and Cobb- Douglas. +RPRWKHWLF3UHIHUHQFHV • Whenever the income offer curve and the Engel curve are straight lines, the quantity demanded of each good varies proportionately with income. In this case, preferences are called KRPRWKHWLF, which implies: ,I 0 [ [ 1 2 , 5 0 , 5⇒0 \ \ 1 2 W[ W[ 1 2 , 5 0 W\ W\ 1 2 , 5, IRU DQ\ W >0 • If conversely, the demand for one good goes up by a greater proportion than income, this good is said to be a 13 OX[XU\JRRG . Also, if the demand for one good goes up by less than proportionately the increase in income, the good is said to be a QHFHVVDU\JRRG. &KDQJHVLQ3ULFHV • When prices change we expect consumers to adjust their optimal choice. If the quantity consumed of one good increases (decreases) when its price decreases (increases), the good is said to be RUGLQDU\. • If the quantity consumed of one good decreases (increases) when its price increases (decreases), such a good is called a *LIIHQJRRG. • If we let p1 change while keeping p2 and m fixed, geometrically this involves pivoting the budget line, which 14 will likely lead to a change in the optimal bundle. If we connect the optimal bundles associated with different value of p1 we get the SULFH RIIHU FXUYH . If we plot the optimal level of consumption against its price, we get the GHPDQGFXUYH . 15 6XEVWLWXWHVDQG&RPSOHPHQWV • We have been talking about perfect substitutes and complements, but often goods turn out to be LPSHUIHFW substitutes and complements. Examples of the former are pens and pencils and of the latter, coffee and sugar. • Since the demand function for each good depends on its own price, but also on the price of the remaining goods, we can use the demand function to ascertain whether two goods are substitutes or complements. In fact: If ∂[1 0 S 1 5 , S2 , P > 0 , good 1 is a substitute for good 2. ∂S2 16 If ∂[1 0 S 1 5 , S2 , P < 0 , good 1 is a complement to good 2. ∂S2 7KH ,QYHUVH 'HPDQG )XQFWLRQ This function gives, for each level of consumption of, say, good 1, the price that would induce the consumer to choose that quantity of the good. Thus, this function, which is denoted as 0 5, has the price as a S [ 1 1 function of the quantity demanded of the good, rather than the quantity as a function of the price. If the demand curve is downward sloping, so is the inverse demand function. 17 0DUNHW'HPDQG Until now, we have been analysing the behaviour of consumers individually considered. To get the total market demand, we have to aggregate all the individual demand functions. 'HILQLWLRQ : The market, or aggregate demand for, say good 1, is the sum of the individual demands over all consumers: ; 1 0 S 1 , S2 , P1 ,..., P = ∑ [ 1 5 =1 0 S 1 5 , S2 , P , where L indexes consumers. • Even though the levels of income available to each consumer can differ, it is convenient to think of a UHSUHVHQWDWLYHFRQVXPHU that faces prices p1 and p2 and has income M (the aggregate level of income). So we can analyse the market demand using basically the same concepts and instruments that we used for the consumer individually considered. 18 • Notice that the above inverse market demand function is depicted holding the prices of all other goods and the levels of income constant. Whenever these change the demand curve shifts. ([DPSOH : Adding up linear demand curves. 7KHFRQFHSWRI(ODVWLFLW\ One of the main uses of the demand function is to measure how the demand for a good varies with prices and income. In this context, elasticity emerges as a very useful tool. 19 • We could think that the responsiveness of the demand of a good to its price can be given by the slope of the demand curve, since it gives the magnitude of the variation in the quantity demanded that follows a price change. However, that measure is dependent on the units in which quantities and prices are measured. For example, the response of demand of chocolate to a change in price is 1000 times higher when chocolate is measured in grams than when it is measured in kilograms. • To get round this limitation, economists have come up with a unit-free measure of responsiveness called HODVWLFLW\ . • The price elasticity of demand is then defined as the percentage change of quantity demand divided by the percentage change in the price. Denoting price elasticity by ε we have: ε= S GT T GS • Since demand curves are generally downward sloping, the price elasticity will most of the times be negative. For that reason, we will often refer to the absolute value of elasticity. ([DPSOH : Price elasticity of a linear demand curve. Graph 20 • What information does elasticity convey about the demand? %K &K ' ,I ,I ,I ε >1 ε <1 ε =1 HODVWLF GHPDQG LQHODVWLF GHPDQG XQLW − HODVWLF GHPDQG • In general, the elasticity of demand for a good depends largely on the availability of substitutes. If a particular good has many close substitutes then, as the price of that good increases, the consumer will shift way from that good and towards its substitutes, so that the demand suffers a big drop. (ODVWLFLW\DQG5HYHQXH For any firm, it is interesting to analyse what happens to its revenue if it changes the price of the good it produces. • Revenue is defined as: 5 = ST Since an increase in the quantity leads to a reduction in the price, the revenue can either go up or down. Specifically, the direction of the variation in revenue depends on the responsiveness of demand to a given change in price, i.e. on the price demand elasticity. 21 • To establish the relation between revenue and elasticity, let’s define revenue in a bit more rigorous way: 0 5 = 0 5. Differentiating revenue with respect to 5 S S ST S , we get: G5 GS G5 GS = S = S GT GS GT GS +T GS GS , RU +T • If the revenue variation triggered by a price change is positive, then we must have: G5 GS S = GT GS S GT GS + T > 0, +T>0⇔ RU S GT T GS , UH − DUUDQJLQJ = ε > −1 • Referring to the absolute value of elasticity, the expression above amounts to: ε < 1, that is, the revenue variation that follows a price increase will be positive if demand is inelastic, will be negative if demand is elastic and will remain unaltered if demand is unit-elastic. 22 (ODVWLFLW\DQG0DUJLQDO5HYHQXH A firm knows that if it increases the quantity of a good, the price must come down in order to induce consumers to buy the extra amount of good put in the market. Since the quantity increases but the price decreases, the firm to would be interested in knowing what would happen to its total revenue. • To establish the relation between PDUJLQDOUHYHQXH05 and elasticity, let’s define revenue in a slightly different (but still rigorous) way: 0 5 = 0 5 . Differentiating revenue with respect to 5 T S T T T , we get: G5 GT G5 GT = S = S GT GT +T +T GS GT GS GT , , RU RU G5 GT = 1 + = 1 + 1 ε S TGS SGT S • If the marginal revenue associated by a change in quantity is to be positive, then we must have: G5 GT = S 1 − 1 > 0, ε RU WKDW 1 >1⇔ ε >1 ε 23 So, marginal revenue is positive if demand is elastic, will be negative if demand is inelastic and will be zero if demand is unit-elastic. Naturally, if demand is little responsive to changes in prices than the firm must reduce the price a lot to be able to sell the extra amount of the good and that decreases total revenue. 0DUJLQDO5HYHQXH&XUYHV We’ve seen that marginal revenue can be written as: G5 GT = S +T GS GT From that expression, one can see that the T 05 = S when = 0 . After that, 05 < S , since as quantity increases the price must decrease. It turns out that, by increasing the quantity the firm receives less for all the other units of good it was supplying, meaning that MR will be equal to the price minus the revenue it loses from having to sell all the production at a lower price. ([DPSOH : Linear (Inverse) Demand Curves Consider the following linear inverse demand function: 24 0 5= S T D − ET The slope of the associated curve is simply − E , so the MR curve is given by: G5 GT = 0 5+ S T T GS GT = 0 5− S T ET = D − 2ET So, this MR curve has the same vertical intercept as the demand curve, but twice the slope. ,QFRPH(ODVWLFLW\ This concept is used to measure the responsiveness of the demand for a good to changes in income; is defined as the ratio of the percent change in the quantity demanded and the percent change in income; and is given by: ,QFRPH HODVWLFLW\ = GT P GP T When this elasticity is negative, we are in the presence of a LQIHULRU JRRG . If the elasticity is greater than one, we are in the presence of a OX[XU\JRRG. 25