* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download DOC Version

Spectrum disorder wikipedia , lookup

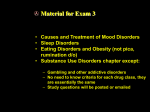

Eating disorders and memory wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Comorbidity wikipedia , lookup

Munchausen by Internet wikipedia , lookup

Causes of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Externalizing disorders wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup