* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Preview the material

Survey

Document related concepts

Women's health in India wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Reproductive health wikipedia , lookup

Women's medicine in antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Maternal physiological changes in pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

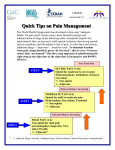

Harm reduction wikipedia , lookup

Transcript