* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Sexually Transmitted Diseases Other than Human

Epidemiology of syphilis wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

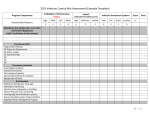

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

INVITED ARTICLE AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES Kevin P. High, Section Editor Sexually Transmitted Diseases Other than Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Older Adults Helene M. Calvet Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services, Long Beach, and the California STD/HIV Prevention Training Center, Berkeley, California Sexually active older adults may engage in activities that put them at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). A brief review of the main STDs among older adults, including the epidemiology, clinical presentations, and diagnosis of and treatment recommendations for such STDs, is presented. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) constitute the most common reportable communicable diseases in the United States, with 1700,000 cases of Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection and 1350,000 cases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection reported in 2000 [1]. The majority of these cases, however, occur among adolescents and young adults, and older adults often are not considered to be at risk for STDs. Studies show that many older adults are sexually active, and many heath care practitioners may not realize that older adults may engage in higher-risk sexual activities. A survey of 1300 men and women ⭓60 years of age, performed by the National Council on the Aging (Washington, DC) in 1998, found that 48% of the respondents were sexually active [2]. Rates of sexual activity were higher among individuals in their 60’s (of whom 71% of men and 51% of women were sexually active), and they decreased among individuals in their 70’s (of whom 57% of men and 30% of women were sexually active) and those in their 80’s (of whom 25% of men and 20% of women were sexually active). Some older adults may have the desire to engage in sexual activity, but they experience barriers, such as psychosocial factors (e.g., depression, performance anxiety, or loss of a partner because of divorce, death, or disability) or medical conditions Received 26 September 2002; accepted 26 November 2002; electronically published 17 February 2003. This article was selected for inclusion in Clinical Infectious Diseases by Dr. Thomas T. Yoshikawa during his time as Aging and Infectious Diseases Section Editor. Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Helene M. Calvet, Long Beach Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2525 Grand Ave., Long Beach, CA 90815 ([email protected]). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003; 36:609–14 2003 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved. 1058-4838/2003/3605-0011$15.00 leading to erectile dysfunction or dyspareunia. The advent of oral medications for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, such as sildenafil citrate (Viagra; Pfizer [3]), is helping some individuals overcome that barrier, with Viagra having been prescribed for 110 million patients since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (Rockville, MD). Although a number of studies have investigated the sexual behavior of older adults, patterns of condom use are not well defined in this group; however, because the risk for STDs is often linked to younger age or risk of pregnancy, older men and women may be less likely to use condoms. In a survey of 12000 Americans ⭓50 years of age who were living in large metropolitan areas, Stall and Catania [4] found that among individuals reporting ⭓1 risk factor for HIV infection (e.g., multiple sexual partners, a sexual partner with a high risk for HIV infection, receipt of a transfusion during 1978–1984, or injection drug use), 73% were sexually active, and 83% of those who were sexually active never used condoms. In a survey of patients at a community-based family practice clinic, Murphree and DeHaven [5] found that among unmarried women, condom use was significantly related to age !31 years, and that patients 145 years of age seldom received counseling about condoms. Although the rates of incidence of the reported STDs (chlamydia infection, gonorrhea, and syphilis) among older adults are low and have remained relatively stable during the past 5 years, the fact that many older adults are sexually active and may not use condoms when indicated can put them at risk for STDs. The present article reviews the epidemiology of STDs in older adults and the common clinical presentations of STDs. Treatment for the diseases, as recommended by the AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • 609 Table 1. Recommended and alternative regimens for the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). Sexually transmitted disease Recommended regimen(s) Alternative regimen(s) Uncomplicated Chlamydia infection Azithromycin, 1 g po, or Dox, 100 mg po b.i.d for 7 days Erythromycin base, 500 mg po q.i.d. for 7 days; or erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 800 mg po q.i.d. for 7 days; or Oflx, 300 mg po b.i.d. for 7 days; or Lvfx, 500 mg po q.d. for 7 days Uncomplicated gonorrheaa,b infection Cefixime, 400 mg po; or Ctri, 125 mg im; or d cd ciprofloxacin, 500 mg po; or Oflx, , 400 c,d mg po; or Lvfx, , 250 mg po Spectinomycin, 2 g im First clinical episode of herpes Acy, either 400 mg po t.i.d. for 7–10 days or 200 mg po 5 times per day for 7–10 days; or Fam, 250 mg po t.i.d. for 7–10 days; or Val, 1 g po b.i.d. for 7–10 days None Episodic therapy for recurrent episodes Acy, either 400 mg po t.i.d. for 5 days, 200 mg po 5 times per day for 5 days, or 800 mg po b.i.d. for 5 days; or Fam, 125 mg po b.i.d. for 5 days; or Val, either 500 mg po b.i.d. for 3–5 days or 1 g po q.d. for 5 days None Suppressive therapy Acy, 400 mg po b.i.d.; or Fam, 250 mg po b.i.d.; or Val, either 500 mg po q.d. or 1 g po q.d. None Primary, secondary, and early latent Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U im ⫻ 1 dose Dox,e 100 mg po b.i.d. for 2 weeks; or Tet,e 500 mg po q.i.d. for 2 weeks; or Ctri,e 1 g im/iv q.d. for 8–10 days, or azithromycin,e 2 g po Late latent and unknown duration Benzathine penicillin G, 7.2 million U, administered as 3 doses of 2.4 million U im, at 1-week intervals Dox, 100 mg p.o. b.i.d. for 4 weeks; or Tet, 500 mg p.o. q.i.d. for 4 weeks Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 18–24 million U/day, administered as 3–4 million U iv q4h for 10–14 days Procaine penicillin G, 2.4 million U im q.d. for 10–14 days, plus probenecid, 500 mg po q.i.d. for 10–14 days Mtz, 2 g po Mtz, 500 mg po b.i.d. for 7 days c c Herpes simplex virus Syphilis Neurosyphilis f Trichomoniasisg NOTE. e e Acy, acyclovir; Ctri, ceftriaxone; Dox, doxycycline; Fam, famciclovir; Lvfx, levofloxacin; Mtz, metronidazole; Oflx, ofloxacin; Tet, tetracycline; Val, valacyclovir. a Cotreatment for Chlamydia infection is indicated unless Chlamydia infection is ruled out by use of sensitive technology. b If gonorrhea is documented and if it persists or recurs, test-of-cure culture is recommended to ensure that the patient does not have an untreated drugresistant gonorrhea infection. c Not recommended for pharyngeal gonococcal infection. d Because of fluoroquinolone-resistant strains in Hawaii and the Pacific Rim, fluoroquinolones should not be the first-line treatment if the patient was exposed in these areas; use of fluoroquinolones for infections acquired in California is also inadvisable. e Consider for treatment of patients with allergy to penicillin; however, because the efficacy of regimens that do not contain penicillin has not been established, and because compliance with some of these regimens may be difficult, close follow-up is essential. If compliance or follow-up cannot be ensured, then the patient should be desensitized and treated with benzathine penicillin G. f Some specialists recommend use of benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million U im weekly for 1–3 weeks after completion of initial treatment. g Documented infection for which treatment failed should be evaluated for metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis. Contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) at 404-639–8371 for more information. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) is summarized in table 1 [6]. CT INFECTION CT infection is predominantly a disease of adolescent girls and young women; its incidence appears to be highest among female adolescents and young women 15–19 years of age (2447 cases per 100,000 such individuals) [1]. The incidence of CT infection in women decreases substantially after 30 years of age, likely 610 • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES because the target cell for CT (i.e., the columnar epithelial cell, which is present on the ectocervix of young women [cervical ectopy]) is replaced by squamous epithelium through the process of squamous metaplasia that occurs with age. Among older adults (those ⭓55 years of age), the reported incidence of CT infection is !5 cases per 100,000 adults, but rates vary among the different ethnic and racial groups. CT can cause a variety of infections, including cervicitis, urethritis, proctitis, follicular conjunctivitis, epididymitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). In younger populations, however, the majority of infections are asymptomatic. No data are available on the proportion of cases of asymptomatic disease in the older population. Many diagnostic tests for CT are commercially available and have been reviewed elsewhere [7], but the most sensitive tests for CT infection of the genitals are the nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), including PCR analysis, ligase chain reaction (LCR), transcription-mediated amplification, and strand-displacement amplification. PCR and LCR have sensitivities of 90%–95%, with specificities of approximately 98%–100% [7]. All of the aforementioned tests are approved for use with urine specimens, which obviates the need for invasive tests. However, in populations in which the prevalence of CT infection is very low, such as older adults, the positive predictive value of these tests can be low; therefore, positive test results should be interpreted with caution, and consideration should be given to use of a second testing modality for confirmation of the results. Routine screening is not indicated for older adults, but diagnostic testing should be done for patients who present with cervicitis, urethritis, or epididymitis and, especially, for patients who report engaging in high-risk sexual practices. Recommended and alternative medications for the treatment of uncomplicated CT infection of the genitals are listed in table 1; treatment of complicated infections is reviewed elsewhere [6]. Although drug resistance has been documented on occasion [8], such resistance is thought to be extremely rare. N. GONORRHOEAE INFECTION Like chlamydia infection, disease due to the gonococcus (GC) is predominantly seen among adolescents, with the highest incidence rates seen among 15–19-year-old female adolescents and young women (716 cases per 100,000 such individuals) [1]. Incidence rates decrease with age, with !10 infections occurring per 100,000 individuals ⭓55 years of age; as with CT infection, rates of incidence of GC infection vary depending on the sex and the ethnic and racial groups of individuals. The clinical presentations of GC are similar to those of CT, with cervicitis, urethritis, proctitis, PID, and epididymitis being the most commonly encountered syndromes; however, GC can also colonize mucosal surfaces asymptomatically. Unlike CT, GC can disseminate hematogenously from any mucosal site, causing disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI). DGI usually presents with arthralgias, tenosynovitis, or arthritis and rash. The rash, which is present in 2 of 3 patients, consists of a few (!30) pustular or necrotic lesions on the distal extremities. Highly sensitive tests for the diagnosis of GC infection include culture, Gram staining of urethral discharge, DNA hybridization probe, or any of the same NAATs that are available for diagnosis of CT infection. Because of its high specificity, culture may be advantageous for older populations in which the prev- alence of GC infection is low, and it also offers the opportunity for sensitivity testing if needed. Routine screening is not recommended for older adults. Although currently recommended therapies for GC infection include the use of fluoroquinolones (FQs), resistance to FQs has been a problem in Hawaii, the Pacific Rim, and parts of Asia for several years, so cephalosporins are the only recommended therapy for infections acquired in these areas [6]. Moderate levels of resistance to FQs recently have been detected in California, so use of FQs in California is not recommended [9]. SYPHILIS The rate of incidence of early (recently acquired) syphilis is low among older adults in the United States. Average incidence rates of syphilis among adults ⭓55 years of age were stable during 1998–2000, with ⭐1 case occurring among 100,000 individuals [1]. Late latent syphilis and, on occasion, neurosyphilis and tertiary forms of syphilis probably are more commonly encountered in this age group. An overview of the different stages of syphilis has been published elsewhere [10]. Tertiary syphilis, although uncommon, can present with cardiovascular findings (aortitis and aortic aneurysm) or gummas, and it usually occurs 5–25 years after infection [11]. Neurosyphilis can occur at any stage of syphilis and can cause a variety of neurological syndromes. Syphilitic meningitis usually occurs early, within months of infection. Strokes due to meningovascular syphilis usually occur 5–12 years after infection, but they may occur earlier. Later neurological manifestations, which occur decades after infection and which usually present in older adults, may include dementia (general paresis), tabes dorsalis, VIIIth nerve deafness, or optic atrophy. Many older adults may be tested for syphilis as part of a workup for strokes, dementia, or other neurological disorders, but the sensitivity of the nontreponemal tests (the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] test and the rapid plasma reagin [RPR] test) for later stages of syphilis may be low; up to 25% of patients with late neurosyphilis have a negative serum VDRL test result [10]. One study estimated that the rate of false-negative results of the serum VDRL test in older populations may be substantial [12], so consideration could be given to using a treponemal test (e.g., the fluorescent treponemal antibody–absorbed test [FTA-ABS] or the particle agglutination test for antibodies to Treponema pallidum (Serodia TP-PA; Fujirebio) if a clinical syndrome suggestive of active late syphilis is present and if the initial result of the nontreponemal test is negative. However, routine use of treponemal tests for older adults with strokes or dementia is not routinely recommended because the yield of such tests is low. CSF analysis, including WBC count, protein level determination, and a CSF VDRL test, is more definitive in the diagnosis AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • 611 of neurosyphilis. Findings of pleocytosis (WBC count, ⭓5 cells/ mL) or an elevated protein level are suggestive of neurosyphilis, and a positive result of a CSF VDRL test is diagnostic (unless the CSF is grossly bloody). The CSF VDRL test, however, is relatively insensitive, and the finding of an isolated elevated protein level in an older individual may be difficult to interpret, because the CSF protein level normally increases with age. Because of problems with the FTA-ABS test’s specificity, it is not recommended that the test be performed on CSF samples; however, because the test has a high sensitivity, a negative CSF FTAABS test result might be helpful in ruling out neurosyphilis in unclear cases [10], such as those for which the CSF VDRL test result is negative but for which suspicion of neurosyphilis remains because of clinical findings or other CSF abnormalities. Penicillin remains the drug of choice for the treatment of syphilis, and, although a number of alternative therapies are possible (see table 1), data regarding regimens that do not contain penicillin are limited, and close follow-up is indicated if a regimen that does not contain penicillin is used. HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS (HSV) Genital HSV infection is not a reportable disease in the United States, but data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which used type-specific serologic testing for detection of HSV type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV type 2 (HSV-2), estimated that ∼20% of the adult population in the United States is infected with HSV-2. HSV-2 infection usually is sexually acquired, with seroprevalence starting to increase at the onset of sexual activity and then increasing with age. According to the findings of NHANES III, the strongest predictors of positive HSV-2 serologic status were female sex, black race or Mexican-American ethnic background, older age, fewer years of formal education, income below the poverty level, greater number of sexual partners during a lifetime, and ⭓1 instance of cocaine use [13]. The seroprevalence of HSV2 in adults ⭓50 of age averages ∼25% but is higher among blacks (seroprevalence, 160%) and Mexican Americans (seroprevalence, ∼40%) [13]. A minority of patients who are seropositive for HSV-2 note the typical vesicular outbreaks, but those without classic symptoms may experience atypical symptoms or may be asymptomatically shedding the virus. In general, clinical symptoms and shedding decrease with time, and the prevalence and frequency of symptoms and shedding in older adults, most of whom have been infected for years, are unknown. Although sensitivity varies depending on the age and stage (primary vs. recurrent) of the lesion, viral culture is useful for the diagnosis of lesions with classic presentations. For patients with atypical or nonulcerative presentations, HSV-2 type-specific serologic testing has been commercially available for several years. Type-specific 612 • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES serologic tests should be considered for patients presenting with bothersome recurrent genital symptoms (e.g., itching, burning, irritation, etc.) without a defined cause. Routine testing of asymptomatic older adults is discouraged because the seroprevalence of HSV-2 is known to be high, because therapy would not be indicated unless the patients was symptomatic, and because the psychological impact of such a diagnosis can be significant. HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS (HPV) HPV infection is considered to be the most common STD, with 10%–20% of younger (age, 15–49 years) sexually active individuals showing molecular evidence of infection, and with up to 60% showing evidence of prior infection [14]. HPV infection is not a reportable disease, but studies suggest that the prevalence of infection is highest among young sexually active women and that it decreases with age. Most infections are subclinical and self-limited, with a minority of patients developing anogenital warts and with ∼10% developing chronic infection, which can predispose the patient to anogenital cancer. The incidence or prevalence of genital warts in older adults is not known, but clinical experience suggests that most cases occur in younger adults. Genital warts may be treated a variety of ways, depending on the location and extent of the disease; the choices of treatment modalities have been reviewed elsewhere [15]. For elderly individuals, a greater concern than genital warts is HPV-related dysplasia or carcinoma. Approximately 25% of new cases of invasive cervical cancer occur among women ⭓65 years of age, and, of women in this age group, only 52% have had a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear performed within 3 years before detection of disease [16]. HPV DNA has been detected in association with up to 93% of cervical cancers, and the most frequently detected HPV types associated with these cancers are types 16 and 18. A comparative study of cervical cancer in older women (those 62–85 years of age) and younger women (those 28–61 years of age) found that the 2 patient groups were similar with respect to the HPV types detected in association with the cancers, the prevalence of HLA dr1501, and the occurrence of p53 mutations, which suggests that the pathogenesis of cervical cancer in older women is similar to that in younger women [17]. The frequency with which Pap smears should be performed in older women is controversial, with many favoring screening that occurs less frequently than on an annual basis for women who have had normal results of recent Pap smears, and there is no consensus on the age at which screening should be discontinued [18]. A new Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytological results [19] and new guidelines for the management of cervical cytological abnormalities [20] outline the approach to abnormalities detected during the screening of older women. Colposcopy with directed biopsy is indicated for most squamous abnormalities, except for atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), for which testing for the high-risk types of HPV-DNA is the preferred method to triage younger women for either immediate colposcopy or moreconservative Pap smear follow-up. For older, postmenopausal women with ASC-US who have clinical or cytological evidence of vaginal atrophy, a reasonable option for follow-up is to prescribe a course of intravaginally administered estrogen (if it is not contraindicated) and to perform a second Pap smear 1 week after completion of the treatment course [20]. If the results of the second Pap smear are negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy, then close follow-up with another Pap smear in 4–6 months is indicated. Another finding of ASC-US or a more severe lesion at either follow-up should be evaluated with colposcopy. A finding of atypical glandular cells in older women is ominous, with a recent retrospective study showing that 17% of women 150 years of age who had atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance had some form of cancer [21]. Uterine cancer was more common than cervical cancer; therefore, in women 135 years of age, the recommended workup of atypical glandular cells includes colposcopy with endocervical sampling and endometrial biopsy. of yeast vaginitis and BV among such women [22]. The epidemiology of trichomoniasis in older women is not well known, but trichomoniasis can be asymptomatic, and long-term carriage of the disease in women has been described. Of note, in the study by Spinillo et al. [22], trichomoniasis was significantly more common among postmenopausal women compared with women of reproductive age, although this study population was likely affected by referral bias. Data from Denmark, however, suggest that trichomoniasis affects a population older than that affected by GC and CT, with the average age of women reported to have trichomoniasis being 39 years, compared with 24 years and 22 years for women with GC and CT, respectively [24]. Evaluation for complaints of vaginitis should include a speculum examination of the cervix and vaginal vault, with examination of vaginal secretions on saline wet mount and KOH preparation and by assessment of vaginal pH. These examinations should yield sufficient information to allow for diagnosis of candidiasis, trichomoniasis, or BV, if present. The sensitivity of wet mount for the detection of Trichomonas organisms is estimated to be ∼70%, so a more sensitive test would be culture, which is now commercially available (InPouchTV; Biomed Diagnostics). Trichomoniasis should be suspected when a women has an abnormal discharge, an elevated vaginal pH level, and evidence of inflammation (increased number of WBCs) without evidence of cervicitis or candidiasis. VAGINITIS Acknowledgments Vaginal discharge is a common complaint of women of childbearing age. Of the 3 main causes of vaginitis in younger women—bacterial vaginosis (BV), candidiasis, and trichomoniasis—only trichomoniasis is clearly sexually transmitted. In older, postmenopausal women, vaginitis is less likely to have 1 of these 3 etiologies, and it is more likely to be the result of the atrophic effects of estrogen deficiency. Spinillo et al. [22] compared postmenopausal women with control subjects of reproductive age who were seen at a vaginitis clinic, and they found that only 38% of the postmenopausal women had BV, trichomoniasis, or candidiasis diagnosed, compared with 53% of the control subjects. The lack of estrogen in older women leads to a thinning of the vaginal epithelium and a reduction in epithelial glycogen content, which leads to alteration in the vaginal pH and microflora. The vaginal microflora of women of childbearing age is predominantly facultative lactobacilli, whereas that of postmenopausal women not receiving estrogen therapy shows not only a lower prevalence of lactobacilli but, also, a 10–100-fold lower concentration of these organisms when present [23]. However, in postmenopausal women, yeasts and the organisms associated with BV (e.g., Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Mycoplasma hominis) were isolated less frequently in postmenopausal women than in women of childbearing age, which possibly explains the lower incidence We thank Thomas Yoshikawa, Gail Bolan, and Jeanne Marazzo for their review of the manuscript. References 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2000. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2001. 2. Dunn ME, Cutler N. Sexual issues in older adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2000; 14:67–9. 3. Pfizer Web site. Available at http://www.pfizer.com/main.html. Accessed 24 January 2003. 4. Stall R, Catania J. AIDS risk behaviors among late middle-aged and elderly Americans. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:57–63. 5. Murphree DD, DeHaven MJ. Does grandma need condoms? Condom use among women in a family practice setting. Arch Fam Med 1995;4: 233–8. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51(RR-6):1–78. 7. Black CM. Current methods of laboratory diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997; 10:160–84. 8. Somani J, Bhullar VB, Workowski KA, Farshy CE, Black CM. Multiple drug-resistant Chlamydia trachomatis associated with clinical treatment failure. J Infect Dis 2000; 181:1421–7. 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—Hawaii and California, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51:1041–4. AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • 613 10. Hook EW III, Marra CM. Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:1060–9. 11. Swartz MN, Healy BP, Musher DM. Late syphilis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh P-A, et al., eds. Sexually transmitted diseases, 3rd ed. US: McGraw-Hill, 1999:487–509. 12. Muic V, Ljubicic M, Vodopija I. Bayes’ theorem–based assessment of VDRL syphilis screening miss rates. Sex Transm Dis 1999; 26:12–6. 13. Fleming DT, McQuillian GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1105–1. 14. Koutsky L. Epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Med 1997; 102 (5A):3–8. 15. Beutner KR, Ferenczy A. Therapeutic approaches to genital warts. Am J Med 1997; 102 (5A):28–37. 16. Cornelison TL, Montz FJ, Bristow RE, Chou B, Bovicelli A, Zeger SL. Decreased incidence of cervical cancer in Medicare-eligible women. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100:79–86. 17. Gostout BS, Podratz KC, McGovern RM, Persing DH. Cervical cancer in older women: a molecular analysis of human papillomavirus types, HLA types and p53 mutations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179:56–61. 614 • CID 2003:36 (1 March) • AGING AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES 18. Paley PJ. Screening for the major malignancies affecting women: current guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 184:1021–30. 19. Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 2002; 287: 2114–9. 20. Wright TC Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA 2002; 287:2120–9. 21. Koonings PP, Price JH. Evaluation of atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance: is age important? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 184:1457–9. 22. Spinillo A, Bernuzzi AM, Cevini C, Gulminetti R, Luzi S, De Santolo A. The relationship of bacterial vaginosis, Candida, and Trichomonas infection to symptomatic vaginitis in postmenopausal women attending a vaginitis clinic. Maturitas 1997; 23:253–60. 23. Hillier SL, Lau RJ. Vaginal microflora in postmenopausal women who have not received estrogen replacement therapy. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25(Suppl 2):S123–6. 24. Dragsted DM, Farholt S, Lind I. Occurrence of trichomoniasis in women in Denmark, 1967–1997. Sex Transm Dis 2001; 28:326–9.