* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Molecular Bose-Einstein Condensates and p

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Molecular Bose-Einstein Condensates and

p-wave Feshbach Molecules of 6Li2

A thesis submitted for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

by

Jürgen Fuchs

Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast Spectroscopy and

ARC Centre of Excellence for Quantum-Atom Optics

Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne

ii

Declaration

I, Jürgen Fuchs, declare that this thesis entitled:

“Molecular Bose-Einstein condensates and p-wave Feshbach molecules of 6 Li2 ”

is my own work and has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, in respect of

any other academic award.

Jürgen Fuchs

Centre for Atom Optics and Ultrafast Spectroscopy

Faculty of Engineering and Industrial Sciences

Swinburne University of Technology

Melbourne, Australia

Dated this day, February 1, 2009

iii

Abstract

This thesis describes the production of molecular Bose-Einstein condensates (BEC) of 6 Li2

dimers and binding energy measurements of p-wave Feshbach molecules. A σ − Zeeman

slower is used to produce a continuous beam of isotopically enriched 6 Li atoms at speeds

low enough to load a magneto-optical trap (MOT). We currently have a flux of slowed

atoms of ∼ 5 · 106 atoms/s loading the MOT with more than 108 atoms. We then transfer

up to 106 atoms in an almost equal spin mixture of the two lowest hyperfine states into an

optical dipole trap.

We achieved condensates in three different crossed optical dipole trap geometries. The

initial low power optical dipole trap was formed using light from a 25 W VersaDisk Yb:YAG

laser at 1030 nm. It consisted of a 15 W beam crossed with a 13 W beam at about 80

degrees with a waist of approximately 30 µm in each beam. By translating the focus of

the second beam we could change the trap geometry from near symmetric to elongated.

Nowadays, we produce condensates in a crossed dipole trap formed by a 100 W fibre laser.

Both arms are focussed to a waist of 40 µm, cross each other at 14 degrees and have laser

powers of ∼80 W and ∼70 W, respectively.

Evaporative cooling is achieved by reducing the laser power near the broad s-wave

Feshbach resonance at 834 G. By tuning to the low magnetic field side (770 G) of the

Feshbach resonance molecules are formed through three-body recombination at sufficiently

low temperatures. Further evaporation leads to the creation of a molecular BEC. After

reducing the laser power by a factor of about 1000 in approximately 3 s we have observed

more than 30 000 condensed molecules. During the evaporation the temperature decreases

from about 100 µK to below 100 nK.

We present measurements of the binding energies of 6 Li p-wave Feshbach molecules

formed in combinations of the |F = 1/2, mF = +1/2i (|1i) and |F = 1/2, mF = −1/2i

(|2i) states. The binding energies scale linearly with magnetic field detuning for all three

resonances. The relative molecular magnetic moments are found to be 113 ± 7 µK/G,

111 ± 6 µK/G and 118 ± 8 µK/G for the |1i − |1i, |1i − |2i and |2i − |2i resonances,

respectively, in good agreement with theoretical predictions.

iv

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this PhD thesis would not have been possible without the help of

many others involved in the project.

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors Wayne Rowlands and Peter Hannaford

for giving me the opportunity to work in this exciting research area of physics at Swinburne

University. Not only have they given me constant guidance and support throughout my

PhD they have also introduced me to the Australian culture which made my stay in

Australia a thoroughly enjoyable experience.

A huge thanks must be given to Grainne Duffy who worked with me for almost three

years. Her constant encouragement and working commitment has been invaluable for our

project from the very beginning. Working with us in the laboratory until late on her very

last day in Australia is a prime example showing her devotion.

Next, I would like to express my thanks to Chris Vale who has contributed so much to

the progress of our project since the moment he arrived at Swinburne. His experience in

the field has accelerated our progress tremendously.

I was very fortunate to work with my fellow graduate students Gopi Veeravalli, Paul

Dyke and Eva Kuhnle. It was a pleasure to work with all of them for which I am very

grateful. I thoroughly enjoyed the great atmosphere amongst us.

Our project has benefited enormously from the contributions of Chris Ticknor. On

many occasions he enlightened us with his wealth of knowledge in this field answering

patiently our most trivial and non-trivial type questions. For this I would like to say many

thanks.

Sharing the laboratory with Heath Kitson has been a great experience both scientifically

and personally. I have learned a great deal from him, for this I would like to say thanks.

Furthermore, I would like to thank Alexander Akulshin who introduced me to the field

of EIT and EIA. I enjoyed the countless discussions in the CAOUS tea room from which

I have learned so much. I am very grateful that he convinced us that it is worthwhile to

study sub-natural resonances in lithium.

Through the years there have been a number of people contributing to our project. I

would like to take the opportunity to say thanks to Markus Bartenstein, Michael Vanner,

Anthony Teal and Richard Moore.

v

I would like to acknowledge the big support from the Atom-Optics laboratory, in particular from Shannon Whitlock, Brenton Hall, Michael Volk, Mandip Singh, Holger Wolff,

Russell Anderson and Russell McLean. It was always fruitful to discuss both experimental

and theoretical issues. Without their help this project would not have moved as fast.

I would like to thank Mark Kivinen for the technical support he has given us. He

manufactured complex experimental components with an outstanding precision and his

working speed was just magnificent. A huge thanks also goes to Tatiana who helped us

with the administrative work load.

I would have suffered significant starvation without the great food from the restaurants

around the campus. I would like to thank Penang Coffee House, Nelayan, Red Bean,

Shanghai Tan, Curry Bazaar and HKSF for the delicious food and, more importantly, all

the people who joined me on those great occasions.

Over the last few years I have visited many laboratories worldwide. I wish to thank all

the people who welcomed me and showed me around their laboratories. In particular, I

would like to thank Andre Schirotzek and Silke and Christian Ospelkaus who even kindly

let me stay in their apartments.

Finally, I would like to express my thanks to my parents for their understanding and

their constant support.

vi

Contents

Declaration

ii

Abstract

iii

Acknowledgements

iv

Contents

vi

List of Figures

xi

1 Introduction

1

2 Interactions in an ultracold gas

5

2.1

Elastic scattering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

2.2

Feshbach resonance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

2.3

Weakly bound Feshbach molecules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10

2.4

p-wave scattering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

3 Quantum degenerate Fermi gases

21

3.1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

3.2

Ideal Fermi gas in a harmonic trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

3.3

Pairing and superfluidity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

3.3.1

Bose-Einstein condensation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

3.3.2

The BCS regime and the BEC-BCS crossover . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

3.3.2.1

The BCS regime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

3.3.2.2

BEC-BCS crossover and unitarity . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

3.3.3

p-wave superfluids

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

vii

30

viii

CONTENTS

4 Experimental set-up

4.1

31

Vacuum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

4.1.1

Oven and oven pumping chamber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

4.1.2

Main vacuum chamber . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

Laser system for 671 nm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

4.2.1

Saturation spectroscopy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

4.2.2

Laser system . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

4.3

Absorption imaging . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

4.4

Feshbach coils . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

4.5

Experimental control . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

4.2

5 Sub-natural Resonances

5.1

49

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

5.1.1

Electromagnetically induced transparency . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

5.1.2

Zeeman coherence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

5.1.3

Coherent population oscillation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

5.1.4

What is special about 6 Li? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

5.2

Experimental set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

5.3

Hyperfine EIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

5.3.1

Vapour cell EIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

5.3.2

Atomic beam EIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

58

Zeeman coherence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

5.4.1

EIT in the 6 Li D1 line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

5.4.2

Sub-natural resonances for a pure four-level atomic system . . . . .

66

5.4

5.5

6

5.4.3

EIA in the Li D2 line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

5.4.4

Modelling and discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

Ramsey spectroscopy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

72

6 Laser cooling of 6 Li

77

6.1

Spontaneous force . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

6.2

Zeeman slower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

6.3

Magneto-optical trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

6.3.1

Optical molasses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

6.3.2

Magneto-optical trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

83

ix

CONTENTS

6.3.3

Experimental realisation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7 Dipole traps

7.1

7.2

7.3

7.4

83

87

Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

88

7.1.1

Single focussed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

88

7.1.2

Crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

89

Low power optical dipole trap set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

91

7.2.1

Intensity stabilisation of the dipole trap laser . . . . . . . . . . . . .

93

7.2.2

Trapping frequency measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

New dipole trap formed by a 100 W fibre laser . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

96

7.3.1

High power crossed dipole trap set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

7.3.2

Trapping frequency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

7.3.3

Lifetime . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Loading the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

8 Bose-Einstein condensation of molecules

105

8.1

Theory of evaporative cooling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

8.2

MBEC in a Low Power Crossed Dipole Trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

8.3

8.2.1

Evaporative Cooling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

8.2.2

Quantum degenerate Bose and Fermi gases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

MBEC in a high power crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

8.3.1

Evaporation and realisation of a molecular BEC . . . . . . . . . . . 115

9 Binding Energies of 6 Li p-wave Feshbach Molecules

9.1

119

Inelastic losses at the |1i − |1i Feshbach resonance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

9.2

Binding energies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

9.3

Transition rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

10 Conclusions

127

10.1 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

10.2 Outlook . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

Bibliography

131

Publications of the author

151

x

CONTENTS

List of Figures

2.1

Feshbach resonance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9

2.2

s-wave scattering length . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11

2.3

Binding energies of Feshbach molecules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12

2.4

Properties of p-wave Feshbach molecules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

3.1

Quantum statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

4.1

Photo of the vacuum set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

6

4.2

Schematic energy level diagram for Li . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

4.3

Saturation spectroscopy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

4.4

Doppler-free spectrum of 6 Li . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

40

4.5

Laser set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

4.6

Typical scan of the spectrum analyser . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

4.7

Absorption imaging set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

5.1

(a) Basic lambda scheme for electromagnetically induced transparency. The

bare atomic states |1i and |2i are coupled by laser light to state |3i. (b)

Atomic eigenstates in the presence of a weak probe and strong pump field,

5.2

resonant with the |1i → |3i and |2i → |3i transition, respectively. . . . . .

Simplified scheme of the experimental set-up.

51

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

5.3

Vapour cell EIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

5.4

Atomic beam EIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

59

5.5

Comparison of the D1 and D2 lines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

5.6

Fluorescence of the D1 line as a function of frequency difference . . . . . .

61

5.7

Zeeman coherence of the D1 line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

62

5.8

Zeeman coherence in a magnetic field . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

xi

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

5.9

Width of EIT fluorescence resonances

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

64

5.10 Sub-natural resonances for the |2S1/2 , Fg = 1/2i → |2P1/2 , Fe = 1/2i transition 66

5.11 EIA in the 6 Li D2 line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

5.12 Splitting of EIA resonances in an external magnetic field . . . . . . . . . .

69

5.13 Fluorescence for the |2S1/2 , Fg = 3/2i → |2P3/2 i transition . . . . . . . . . .

69

5.14 Numerical modelling of probe absorption spectra . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

71

5.15 Set-up used to observe Ramsey fringes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

73

5.16 Ramsey fringes in a medium of EIT and EIA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

74

6.1

Zeeman slower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

6.2

Doppler temperature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

6.3

MOT temperature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

84

7.1

Crossed dipole trap gallery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

87

7.2

Dipole trap potentials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

90

7.3

Set-up of the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

7.4

Elongated crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

93

7.5

Lifetime of the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

7.6

Trapping frequency measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

95

7.7

High power crossed dipole trap set-up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

7.8

Radial trapping frequency measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

7.9

Axial trapping frequency measurements

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

7.10 Lifetime of the crossed dipole trap in different geometries . . . . . . . . . . 102

7.11 Absorption images of the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

7.12 Loading of the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

8.1

Evaporative cooling in the crossed dipole trap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

8.2

Absorption images of the molecular gas durig evaporative cooling . . . . . 111

8.3

Integrated cross sections along the weakest trapping axis . . . . . . . . . . 112

8.4

In situ absorption images of a trapped molecular BEC and DFG . . . . . . 113

8.5

Observation of a degenerate Fermi gas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

8.6

Evaporative cooling in the crossed dipole trap formed by the fibre laser . . 115

8.7

Absorption images during evaporative cooling in the high power dipole trap

and integrated cross sections along the weakest trapping direction . . . . . 117

LIST OF FIGURES

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

xiii

Atom loss at the |1i-|1i 6 Li p-wave Feshbach resonance . . . . . . . . . . . 121

Magneto-association spectrum for the |2i − |2i p-wave Feshbach resonance

122

Binding energies of p-wave Feshbach molecules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

Magneto-association rate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

xiv

LIST OF FIGURES

Chapter 1

Introduction

The discovery of superconducting mercury in 1911 by K. Onnes [Onn11] marked the starting point of the field of fermionic superfluidity and superconductivity. Subsequent experimental breakthroughs have been the realisation of liquid 3 He in 1972 [Osh72] and the

(at the time) surprising discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates in

1986 [Bed86]. However, not all aspects of these exciting phenomena are currently understood in depth.

Laser and evaporative cooling of neutral atoms has opened the way to studies of quantum degenerate bosonic and fermionic systems in table-top experiments. These dilute

gases have received enormous attention both theoretically and experimentally since the

first experimental realisation of Bose-Einstein condensates in 1995 [And95, Dav95, Bra95].

Experiments on ultracold Fermi gases lagged somewhat behind at that time. Certainly,

one reason was purely technical since evaporation of fermions requires more sophisticated

experimental set-ups. This is because collisions which are necessary for rethermalisation

during evaporative cooling are frozen out in an ultracold one-component fermionic gas due

to the Pauli exclusion principle. Thus, initially the interest in degenerate fermionic gases

was in the shadow of bosonic systems because “non-interacting” Fermi gases did not seem

attractive. It is an irony of life that experiments on ultracold fermionic gases nowadays

particularly focus on strongly interacting and strongly correlated systems.

Rapid progress has been made in fermionic systems through the use of magnetic field

Feshbach resonances which can dramatically alter the two-body interactions. These scattering resonances occur when the energy of two colliding atoms is Zeeman tuned to coincide with a bound molecular state. The stability of fermionic systems near such res1

2

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

onances came somewhat as a surprise and it is, in essence, due to the Pauli exclusion

principle [Pet04]. Bosonic systems, on the other hand, suffer from frequent inelastic collisions near Feshbach resonances and this ultimately limits the tunability of the interaction

strength. Feshbach resonances play a key role in studies of ultracold Fermi gases and have

led to the experimental realisation of long-lived bosonic molecules comprised of fermionic

atoms [Reg03a, Reg04a, Cub03, Str03, Joc03a] and the Bose-Einstein condensation of these

molecules [Joc03b, Gre03, Zwi03]. This thesis describes two different all-optical set-ups

employed to produce molecular condensates of 6 Li dimers in our laboratory.

The resonant superfluid phase which occurs in the crossover region between a molecular BEC and a Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) state of Cooper pairs is of particular

interest [Hol01]. Since the first experimental investigations in this regime [Reg04b, Zwi04,

Chi04a, Bar04b, Bou04, Kin04a, Par05] progress to date has been extremely rapid with

studies of collective oscillations [Bar04a, Alt07, Kin04a, Kin04b], universal behaviour [Kin05,

Tho05a, Luo07, Ste06, Par06a], superfluidity [Chi06, Zwi05, Zwi06b, Sch07b, Sch08], polarised Fermi gases [Par06a, Zwi06a, Shi06, Par06b, Sch07a, Shi08] and the speed of

sound [Jos07].

An outstanding goal in cold atom physics is to extend the previous work on s-wave

paired condensates to superfluids of pairs with nonzero angular momentum. Recent experiments have shown the production of p-wave Feshbach molecules of

6

40

K2 [Gae07] and

Li2 [Ina08]. In this thesis we present our binding energy measurements of the three p-wave

Feshbach molecules formed by all three combinations of the two lowest hyperfine states.

The techniques and results presented in this thesis may provide a foundation towards the

production and observation of long-lived p-wave Feshbach molecules made from fermionic

atoms.

This thesis deals with the production of molecular Bose-Einstein condensates of 6 Li2

dimers in two different all-optical set-ups. Furthermore, we present the studies on the

binding energies of p-wave Feshbach molecules. The thesis is structured as follows: Firstly,

in chapters 2 and 3 we focus on the scattering and many-body properties of these ultracold

Fermi gases. A brief description of the vacuum apparatus and laser system is given in

chapter 4. Experiments on sub-natural resonances employing the atomic 6 Li beam is

the topic of chapter 5 which have been published in [Fuc06, Fuc07a]. Our laser cooling

and dipole trapping is presented in chapters 6 and 7. Then, the production of molecular

Bose-Einstein condensates in different geometries is described in chapter 8 which is partly

3

published in [Fuc07b]. Parts of the last experimental chapter 9 on p-wave molecules have

been published in [Fuc08]. The main results are summarised and a brief outlook is provided

in chapter 10.

4

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 2

Interactions in an ultracold gas

In recent years there has been enormous progress in the study of ultracold Fermi gases.

Experimentally, the advances were mainly driven by the use of magnetic field Feshbach

resonances which can dramatically alter the two-body interactions. The breath-taking

experiments in the BEC-BCS crossover have utilised broad s-wave Feshbach resonances in

either 6 Li [Zwi04, Bar04b, Bou04, Kin04a, Par05] or

40

K [Reg04b]. Additionally, in our

experiments we are also interested in extending this work on s-wave pairing to pairs with

nonzero angular momentum.

Here, we briefly discuss basic scattering theory and aspects of Feshbach resonances

and Feshbach molecules which are relevant for our experiments. We only discuss twobody interactions because in typical experiments on ultracold gases the mean interparticle

separation (n−1/3 ∼ 1 µm) is much larger than the spatial range of the interatomic potential

(∼ 3 nm). This chapter is kept short as it is meant to be a reminder rather than an

introduction to the field. There have been a number of extensive reviews on this topic,

e.g. [Dal99].

2.1

Elastic scattering

Two-body scattering problems are commonly described in the centre of mass frame which

reduces the dimensionality from 6 to 3 as only the relative motion is relevant. Hence,

our scattering problem can be described by a particle with momentum ~k and reduced

mass mr (equal to half the atomic mass m) that is scattered by the interaction potential

V (r). The non-relativistic Schrödinger equation for a spherically symmetric potential, i.e.,

5

6

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

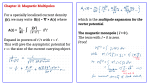

V (r) = V (r), is given by

~2

∇2 + V (r) Ψ(r) = EΨ(r).

2mr

(2.1)

(~k)2

E=

>0

2mr

(2.2)

In scattering processes V (r) is the interatomic potential and

is the kinetic energy of the incoming particle. Solutions with E = −EB < 0 give rise to

discrete bound states with a binding energy EB . Generally, eigenstates to this centrally

symmetric potential are of the form

Ylm (θ, φ)

uk,l,m(r)

,

r

(2.3)

where Ylm (θ, φ) are the spherical harmonic functions. The functions uk,l,m(r) obey the one

dimensional radial Schrödinger equation with the effective radial potential

Veff (r) =

~2 l(l + 1)

+ V (r).

2mr r 2

(2.4)

The centrifugal barrier Vl = ~2 l(l + 1)/(2mr r 2 ) suppresses collisions with l > 0 for low

energies. In lithium, for example, this centrifugal barrier is ∼ 7kB ×mK for l = 1 [Jul92],

where kB is Boltzmann’s constant. This barrier is significantly larger than the average

kinetic energy of laser cooled atoms. Hence, we typically only need to consider l = 0

collisions, also called s-wave collisions. One important exception to this will be discussed

in section 2.4.

In scattering processes it is usual to describe the wave function Ψk (r) as the sum of

the incoming plane wave Ψinc (r) and the scattered outgoing spherical wave for r → ∞

Ψsc (r). An arbitrary incoming wave packet can be described as a superposition of many

plane waves. This yields

Ψk (r) ∼ Ψinc (r) + Ψsc (r) = eik·r + f (k, θ)

r→∞

eikr

.

r

(2.5)

The function f (k, θ) is the scattering amplitude that for a given energy E only depends

on the scattering angle θ. Due to the azimuthal symmetry the scattering amplitude can

be expanded in spherical harmonic functions Ylm with m = 0 [Gur07]

f (k, θ) =

∞

X

p

l=0

4π(2l + 1)fl (k)Yl0 (θ).

(2.6)

7

2.1. ELASTIC SCATTERING

Here, fl (k) is the partial wave scattering amplitude which can be written in terms of the

partial wave phase shifts δl (k)

1

ei2δl − 1

=−

2ik

−k cot δl (k) + ik

k 2l

k 2l

∼

=

.

=

−k 2l+1 cot δl (k) + ik 2l+1

vl−1 − 21 k 2 kl + ik 2l+1

fl (k) =

(2.7)

(2.8)

The form of the partial wave scattering amplitude (equation 2.7) follows from comparing

asymptotic results to the Schrödinger equation for r → ∞ and equation 2.5. In the second

step of equation 2.8 we parametrise the scattering amplitude for low energies by Taylor

expanding k 2l+1 cot δl (k) in powers of k 2 (which is proportional to the energy). This is

meaningful due to physical restrictions on the scattering amplitude [Gur07]. Therefore, at

small k the scattering amplitude becomes

fl (k) ∝ k 2l ∝ E l .

(2.9)

In many experiments we are interested in the scattering cross section. The differential

cross section can be related to the scattering amplitude by

dσ

= |f (k, θ)|2 ,

dΩ

(2.10)

where Ω is the solid angle. From this, one can calculate the total cross section

σ(k) =

∞

X

σl (k)

with

σl (k) = 4π(2l + 1)|fl (k)|2 =

l=0

4π

(2l + 1) sin2 δl (k).

k2

(2.11)

From equations 2.9 and 2.11 it follows that the energy dependence of the cross section

σl (E) ∝ E 2l in the low energy limit. Hence, the s-wave scattering cross section becomes

constant at low energies whereas higher order cross sections vanish as E → 0. This

confirms that at low temperatures scattering processes with small l dominate as we have

already discussed previously. The different threshold behaviour for l = 0 and l = 1 at low

temperatures has been observed in reference [DeM99a].

If the two colliding particles are identical, quantum statistics has to be included in the

theory. At the low temperatures we are dealing with, this becomes particularly important

and changes the scattering properties significantly. Quantum mechanics requires the wave

function to be symmetric for bosons and anti-symmetric for fermions under interchanging

both particles. From this it follows that the cross section for a partial wave l of two identical

8

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

colliding fermions (bosons) vanishes for even (odd) l and doubles for odd (even) l. Hence,

for identical particles equation 2.11 becomes [Dal99]

Bosons :

Fermions :

8π X

(2l + 1) sin2 δl (k)

k 2 l even

8π X

σ(k) =

(2l + 1) sin2 δl (k).

k2

σ(k) =

(2.12)

(2.13)

l odd

The important consequence is that identical fermions do not scatter in the s-wave channel. Hence, due to the symmetry principle and the centrifugal barrier, ultracold identical

fermions are typically non-interacting.

s-wave scattering

The s-wave partial wave scattering amplitude f0 (k) can be parametrised by Taylor expanding k cot δ0 (k)

1

−k cot δ0 (k) ∼

(2.14)

= a−1 − k 2 r0 .

2

Here, we define the scattering length a and the effective range of interaction r0 . A negative

(positive) scattering length results in an overall attractive (repulsive) interaction. The

magnitude and sign of the scattering length for a single potential are mainly determined

by the highest bound molecular state. If it is just below the continuum the scattering

length is large and positive. The effective range of interactions is typically on the order

of the spatial range of the interatomic potential. In the s-wave limit for a point-like

interaction (r0 = 0) the scattering cross section for distinguishable particles is according

to equation 2.11

4πa2

.

(2.15)

1 + k 2 a2

In the weakly interacting limit (ka ≪ 1) this gives σ0 (k) = 4πa2 , whereas in the strongly

σ0 (k) =

interacting limit the scattering cross section σ0 (k) = 4π/k 2 becomes independent of the

scattering length. Instead, it is proportional to the spread of the wave packet of the atom

represented by the square of the de Broglie wave length

s

2π~2

,

λdB =

mkB T

where T is the temperature of the gas and m the mass of the particles.

(2.16)

9

2.2. FESHBACH RESONANCE

(a)

free atoms

(b)

∆E = ∆µ × B

energy

energy

closed channel

virtual bound state

Feshbach molecule

open channel

free atoms

magnetic field

interatomic distance

Figure 2.1: (a) Due to the different magnetic moments the closed channel can be shifted

relative to the open channel by applying a magnetic field. Tuning a bound state of the

closed channel to degeneracy with the continuum of the open channel leads to a Feshbach resonance. (b) Energy dependence of the molecular and atomic states with respect

to magnetic field. Due to the avoided crossing Feshbach molecules can be adiabatically

transferred into free atomic pairs and vice versa.

2.2

Feshbach resonance

It was an important breakthrough in ultracold atom experiments to discover the possibility to tune the scattering length, and hence the interactions, by applying magnetic

fields near Feshbach resonances. These scattering resonances [Fes62] have been predicted

by [Tie93] for ultracold atomic gases. Experimentally, they were first discovered by Inouye

et al. [Ino98] in

23

Na and Courteille et al. [Cou98] in

85

Rb.

To understand the underlying principle, we consider two molecular potentials for atoms

in different hyperfine states (see figure 2.1). The incoming atoms scatter in the lower

potential also named an open channel. The upper potential is typically referred to as the

closed channel because it is energetically not accessible at R = ∞. The highest lying

vibrational levels of the closed channel can lie above the continuum of the open channel.

The scattering properties are altered by the coupling of both channels which is typically

due to the Coulomb or hyperfine interaction [Bur02]. A bound state of the closed channel

just below the continuum of the open channel gives rise to a large positive scattering

10

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

length. Similarly, a virtual bound state just above the continuum yields a large and

negative scattering length. If the molecular state has a different magnetic moment to that

of the free atoms an external magnetic field shifts the potentials with respect to each other.

Hence, by applying a magnetic field it may be possible to bring a bound state of the closed

channel into degeneracy with the continuum giving rise to a Feshbach resonance. At the

position of the Feshbach resonance the scattering length diverges. Near the resonance the

scattering length behaves as

a(B) = abg 1 −

∆ ,

B − B0

(2.17)

where abg is the background scattering length, B0 the position of the resonance and ∆

the width of the resonance. It is usual to distinguish between broad and narrow Feshbach

resonances. Broad Feshbach resonances are characterised by kF |r0 | ≪ 1, where kF is

the Fermi number which will be properly introduced in equation 3.11. One finds for

broad resonances that the many-body properties of the ultracold gas are determined by

the dimensionless parameter kF a, whereas in narrow resonances (kF |r0 | & 1) the effective

range of interactions becomes crucial [Gio07].

Figure 2.2 shows the scattering length versus magnetic field of two lithium-6 atoms in

the two lowest hyperfine ground states [Bar05]. The unusual broad Feshbach resonance at

834 G has a width of 300 G and was predicted by Houbiers et al. [Hou98]. Furthermore, an

∼ 100 mG wide resonance at 543 G has been found and was first observed by Dieckmann

et al. [Die02]. The scattering length starts off near zero in zero magnetic field. With

increasing magnetic field the scattering length decreases to a local minimum of -300 a0

at 325 G before crossing zero at 530 G. At large magnetic fields the scattering length

approaches the very large triplet scattering length of 2200 a0 .

2.3

Weakly bound Feshbach molecules

Extending the work on ultracold atoms to ultracold molecules is of great interest. The

first production of cold dimers was demonstrated by photoassociating cold atoms [Fio98].

Although this is now a very established method the conversion efficiency was limited in

the experiments performed so far. In 1999, Abeelen et al. [Abe99] pointed out that it is

possible to create ultracold molecules near Feshbach resonances. The main idea is shown in

figure 2.1(b). The dependence of energy on the magnetic field is depicted for the free atoms

11

scattering length [1000 a0 ]

2.3. WEAKLY BOUND FESHBACH MOLECULES

4

2

0

−2

−4

0

500

1000

magnetic field [G]

1500

Figure 2.2: s-wave scattering length of two colliding 6 Li atoms in the two lowest hyperfine

states |F = 1/2, mF = +1/2i (|1i) and |F = 1/2, mF = −1/2i (|2i) as a function of

magnetic field. Of particular interest are the broad Feshbach resonance at 834 G and the

very narrow one at 543 G.

in the open channel and the bound state in the closed channel. Due to an avoided crossing

the molecular state below the resonance is connected to the free atom state above the

resonance. The Feshbach molecule above the resonance is unstable and is hence referred

to as a virtual bound state.

In 2002, Donley et al. were the first to observe a signature of molecules created near

a Feshbach resonance [Don02]. In a Ramsey type experiment they observed Ramsey

fringes between molecules and atoms. Regal et al. directly observed creation of molecules

by adiabatically sweeping across a Feshbach resonance in fermionic

40

K [Reg03a]. This

6

was followed by similar experiments on an ultracold gas of Li [Joc03a, Str03, Cub03].

Furthermore, creation of molecules has also been reported in bosonic systems, such as

Cs [Her03], Rb [Dür04] and Na [Xu03]. Detailed reviews on Feshbach molecules can be

found in [Koh06, Hut06].

It is characteristic that these Feshbach molecules in the s-wave channel are only very

weakly bound. The binding energy EB = −E of these molecules represents the en-

12

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

energy

molecules

(b)

atoms

|ν, ν′i

...

...

|0, 1i , |1, 0i

|νm i

|0, 0i

...

...

Eb

|1m i

|0m i

binding energy [kB µK]

(a)

1

10

0

10

−1

10

−2

10

650

700

750

800

magnetic field [G]

Figure 2.3: (a) Lowest vibrational levels of bound molecules and free atom pairs. The binding energy of Feshbach molecules corresponds to the energy difference between the lowest

molecular and atomic vibrating states. (b) Magnetic field dependence of the binding energy

of 6 Li2 Feshbach molecules below the broad s-wave resonance according to equation 2.18.

ergy difference between the lowest molecular and atomic vibrating states as depicted in

figure 2.3(a). It corresponds to the poles of the s-wave scattering amplitude f0−1 (k =

√

2mr EB ) = 0 which yields

r0 i

~2 h

1+

EB = −

2mr a2

a

for

r0 ≪ a.

(2.18)

As expected, the binding energy depends mainly on the scattering length a. Thus, by

varying the magnetic field near a Feshbach resonance it is possible to alter the binding

energy dramatically. In fact, the binding energy depends quadratically on the magnetic

field detuning (B0 − B). In figure 2.3(b) we show the binding energy of 6 Li2 Feshbach

molecules as a function of magnetic field below the broad resonance in the two lowest

hyperfine states. It was calculated using equation 2.18 with r0 ∼ 3.2 nm [Gio07].

Compared to tightly bound molecules the particle separation of weakly bound molecules

can be orders of magnitudes larger. This can be seen by considering the wave function.

Due to the large inter-particle separations compared to the classical turning point the wave

13

2.3. WEAKLY BOUND FESHBACH MOLECULES

function can be approximated by [Koh06]

Ψ(r) = √

1 exp(−r/a)

.

r

2πa

(2.19)

This gives a mean particle separation of hri = a/2.

To achieve a molecular Bose-Einstein condensate the scattering properties of the Fes-

hbach molecules are of importance. It has been shown that the scattering length for

dimer-dimer collisions add and dimer-atom collisions aad can be related to the atom-atom

scattering length a [Pet04, Pet05]. The theoretically calculated values

add = 0.6a

and

aad = 1.2a,

(2.20)

are in good agreement with experimental data [Joc03b, Cub03].

Collisional stability of Feshbach molecules

Weakly bound Feshbach molecules are in the highest rovibrational molecular state. Therefore, inelastic atom-molecule and molecule-molecule collisions may lead to relaxation into

deeply bound states releasing enough energy for the molecules to escape the trap. It has

been found that this relaxation process is quite rapid for Feshbach molecules comprised of

bosonic atoms. Typical lifetimes are on the order of 1 ms which is too short to achieve

rethermalisation of the ensemble. The high inelastic loss rate near Feshbach resonances also

limits the tunability of the atomic interactions in bosonic gases [Ste99a]. Inelastic collisions

can be avoided in a three dimensional lattice by loading exactly two atoms per lattice site.

In a subsequent magnetic sweep one molecule per lattice site can be formed [Vol06].

The situation is very different for weakly bound molecules made from fermionic atoms.

This has been theoretically investigated by Petrov et al. [Pet04] for systems where the scattering length is much larger than the range of the interatomic potential. They showed that

for molecules in long range states, e.g., obeying the wave function given by equation 2.19,

the atom-molecule and molecule-molecule inelastic collisions are suppressed due to Fermi

statistics. This is because the collisional relaxation is a three-body process where the three

atoms have to get as close to each other as the range of interactions. In a two species spin

mixture the third atom is necessarily identical to one of the atoms bound in the molecule.

Pauli blocking then prevents the third atom from getting as close to the molecule as required for inelastic collisions. In [Pet04] the atom-dimer αad and dimer-dimer αdd collision

14

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

rates that lead to transitions in tightly bound molecules have been calculated and have the

following dependence on the scattering length

αad ∝ a−3.33

and

αdd ∝ a−2.55 .

(2.21)

It is remarkable that the inelastic collision rates decrease as the scattering length a increases. This leads to very stable systems close to Feshbach resonances where the binding

of the molecule is particularly weak. The inelastic loss rates are in agreement with experimental observations [Reg04a, Bou04]. Reference [Pet04] also shows that the inelastic

collision rate is significantly smaller than the elastic scattering rate (see chapter 8.1 and

equation 2.20). This allows efficient evaporative cooling of weakly bound molecules near

Feshbach resonances which is the fundamental basis for nearly all our experiments.

Three-body recombination

Many groups produce weakly bound Feshbach molecules from a BEC or degenerate Fermi

gas by adiabatically sweeping over the Feshbach resonance making use of the avoided

crossing as depicted in figure 2.1(b). However, as was shown by Jochim et al. [Joc03a]

it is also possible to produce molecules by three-body recombination from a thermal gas

of atoms. When the scattering length is such that the binding energy EB ∼

= ~2 /ma2 is

higher than the atomic temperature (but lower than the depth of the potential confining

the cloud) a trapped mixture of atoms and molecules in thermodynamic equilibrium may

exist. As the temperature decreases below the binding energy of the molecules, the equilibrium favours molecules, which are formed by three-body recombination. This enables

the production of cold molecules by evaporative cooling (which will be explained in more

detail in section 8.1) of an incoherent mixture of atoms in states |F = 1/2, mF = +1/2i

(|1i) and |F = 1/2, mF = −1/2i (|2i), on the a > 0 side of a Feshbach resonance. This

molecule production process has been studied theoretically [Chi04b, Kok04, Wil04]. According to [Chi04b], the molecular phase space density Dmol and the atomic phase space

2 EB /kB T

density Dat (see section 3.1) are related by Dmol = Dat

e

. This suggests effective

molecule production at large binding energies. However, this is not an ideal situation in

cold atom experiments because the binding energy of the molecule is converted into kinetic

energy which heats up the cloud.

2.4. P -WAVE SCATTERING

2.4

15

p-wave scattering

For identical fermions s-wave scattering is prohibited due to quantum statistics. Hence,

p-wave collisions become the dominant scattering process. However, only close to p-wave

Feshbach resonances is p-wave scattering typically noticeable in cold atom experiments

due to the centrifugal barrier. These scattering resonances are very similar to s-wave

resonances; however, the closed channel involved in p-wave resonances is a molecular state

with finite angular momentum l = 1. It is unique to atom pairs with nonzero angular

momentum that a quasi-bound molecular state exists on the high magnetic field side of

the resonance. This state possesses positive energy and is only temporarily bound by the

centrifugal barrier [Kno08]. p-wave resonances are generally narrow as the colliding atom

has to tunnel through the centrifugal barrier to be affected by the bound state.

Initial experiments on p-wave Feshbach resonances in ultracold Fermi gases have focussed on 6 Li and

40

K. In 6 Li, three p-wave resonances have been identified in all com-

binations of atoms in the |1i and |2i states. Atom loss associated with these resonances

has been observed at fields of 159 G, 185 G and 215 G due to the |1i − |1i, |1i − |2i and

|2i − |2i resonances, respectively [Zha04, Sch05]. Inelastic and elastic collision rates for

the |1i − |2i and |2i − |2i resonances were calculated in [Che05c]. Evidence of molecule

formation via adiabatically sweeping the magnetic field across the |1i − |2i resonance was

seen in [Zha04], but no long lived trapped molecules were detected. Enhanced three-body

loss has also been reported for the 159 G p-wave resonance through interactions with a

second species (87 Rb) [Deh08]. Somewhat more progress has been made using

40

K includ-

ing measurements of the field dependent elastic scattering cross-section [Reg03b] and the

observation of the doublet corresponding to the different projections of the angular momentum [Tic04, Gün05], where the weak dipole-dipole interaction lifts the degeneracy of

the ml = ±1 and ml = 0 projections. In 2007, Gaebler et al. succeeded in creating p-wave

molecules from a gas of spin polarised

40

K [Gae07] using both magneto-association and

three-body recombination and measured the binding energies and lifetimes in the bound

and quasi-bound regimes. Unfortunately, these molecules experience rapid decay to lower

lying atomic spin states through dipolar relaxation and their lifetime was limited to less

than 10 ms. This presents a major impediment to creating a

40

K p-wave superfluid (see

6

section 3.3.3). In Li, however, the |1i − |1i p-wave resonance involves two atoms collid-

ing in their lowest spin state; hence molecules produced on this resonance would not be

16

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

susceptible to dipolar relaxation. These molecules therefore have the potential to be much

longer lived and may prove to be a viable avenue to studies of p-wave superfluidity with

ultracold atomic gases. Dipolar relaxation is also suppressed for the ml = 1 projections

of the |1i − |2i and |2i − |2i resonances due to angular momentum conservation. How-

ever, these states are degenerate with other unstable ml projections, unlike the |1i − |1i

resonance which is stable for all projections. Recently, Inada et al. reported the formation of p-wave molecules in all three combinations of the two lowest hyperfine states of

6

Li [Ina08]. Furthermore, elastic and inelastic collision rates were determined. However, it

is noteworthy that Inada et al. reported in recent experiments a 1/e lifetime of only up to

approximately 20 ms for a gas of |1i − |1i molecules.

The appropriate parametrisation of the p-wave scattering amplitude (see equation 2.8)

is found by Taylor expanding k 3 cot δ1 (k). This results in a p-wave scattering amplitude of

f1 (k) =

k2

−v −1 + 12 k0 k 2 − ik 3

for

1

− k 3 cot δ1 (k) ∼

= −v −1 + k 2 k0 .

2

(2.22)

Here, v is the scattering volume which is related to the p-wave scattering length v = a3p . The

characteristic wave vector k0 , which is negative everywhere, corresponds to the effective

range in s-wave scattering. Both v and k0 depend on the magnetic field but not on the

collision energy. For small k the scattering amplitude depends linearly on the scattering

energy, i.e.,

2mr E

.

(2.23)

~2

Near p-wave Feshbach resonances the scattering volume can be tuned by varying the

f1 (k) ∝ k 2 =

magnetic field and it diverges at the resonance and changes its sign. For low collision

energies the p-wave scattering amplitude just below the resonance (vk 2 ≫ 1 and k ≪ k0 )

becomes f1 (k) ≈

1

k0

which is typically on the same order of magnitude as non-resonant

2

s-wave scattering. For a collision energy E ≈ − 2m2~r k0 v the scattering amplitude becomes

unitary f1 (k) ≈ ki .

Properties of p-wave molecules

The binding energy of resonant states can be found by analysing the poles of the scattering

amplitude in equation 2.22. In the case of low energies one can neglect ik which results in

a binding energy of

EB ∼

=

~2

.

mr vk0

(2.24)

2.4. P -WAVE SCATTERING

17

For v > 0 this corresponds to a real bound state while for v < 0 we obtain a quasibound state. Even close to resonance one needs two parameters, in this case v and k0 , to

describe the binding energy accurately. This is in contrast to s-wave molecules, where the

scattering length a is sufficient to determine the binding energy near resonance, as seen

in equation 2.18. The reason for this is that the properties of s-wave bound states in the

vicinity of a Feshbach resonance are hardly affected by the short-range properties of the

potentials due to the large spatial extent of the molecule. Because of the centrifugal barrier

this is not the case for p-wave Feshbach molecules, as we will see shortly.

The binding energy of p-wave molecules scales linearly with respect to the magnetic

field detuning. This is also in contrast to weakly bound s-wave molecules which have a

squared dependence. The consequence of this is that the binding energy of p-wave molecules

increases much faster as we increase the magnetic field detuning. If the binding energy

of the p-wave molecule is greater than the trap depth the molecules will escape the trap

after being formed from free atoms. p-wave molecule production is therefore limited to the

vicinity of Feshbach resonances.

The properties of p-wave molecules are essentially constant across the resonance, in

strong contrast to s-wave molecules [Koh06]. To illustrate this we first consider the closed

channel amplitude, Z [Koh06, Gub07]. The wavefunction can then be written in terms of

the open channel component, ψo , and ψc which represents all closed channel components

yielding

|ψmol i =

√

Z|ψc i +

√

1 − Z|ψo i.

(2.25)

Physically, the closed channels correspond to channels with different (separate) atomic

hyperfine quantum numbers which are energetically forbidden at long range, but couple to

the open channel at short range via spin-exchange. In figure 2.4 we have plotted Z (solid

blue) for 6 Li p-wave molecules as a function of detuning (right vertical axis) on the bound

side of the resonance. Z was obtained directly from the full closed-coupled calculation

performed by C. Ticknor. It is roughly 0.82 for all detunings shown. This property is

essentially constant across the resonance until the detuning is extremely small (< 5 mG).

In figure 2.4 we have also plotted the size of the p-wave molecules (black) as a function

of detuning. In addition we have separately plotted the size of a dominant closed channel

(red dashed), the open channel (red), and an analytic open channel model (dashed brown,

see below). We can understand this behaviour by expressing the size of the molecule in

18

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

Figure 2.4: Properties of p-wave Feshbach molecules as a function of magnetic field detuning. The size of the molecule (black), open (red) and closed (dashed red) channel

components are shown. The closed channel amplitude, Z (blue, right vertical axis), is

shown as a function of detuning.

terms of open and closed channels:

rmol = Zrc + (1 − Z)ro ,

(2.26)

where ri = hψi |r|ψi i, and i = {mol, o, c}. This shows that the size of the molecule very

closely follows Z. In addition to this, both ro and rc are much smaller than those in the s-

wave molecules. This fact arises due to the centrifugal barrier confining the wavefunction to

short range. Near an s-wave resonance the molecules are open channel dominated because

Z → 0 as the magnetic field detuning, δB = B − B0 , goes to zero [Koh06]. This means

s

rmol

∼ ro (equation 2.26). From the asymptotic form of the s-wave radial wavefunctions

s

(equation 2.19) one finds ro is remarkably large for s-wave molecules: rmol

= a/2 where a

is the s-wave scattering length. In contrast, p-wave molecules carry much more amplitude

at short range due to the extra radial dependence in the asymptotic form of the radial

wavefunction

ψop (r)

e−kr

∝

r

1

1+

.

kr

(2.27)

One can use equation 2.27 to make an analytic approximation to the size of the open channel

p

√

using ~k = 2mr EB = mµm |δB|, where mr is the reduced mass and µm is the magnetic

2.4. P -WAVE SCATTERING

19

moment of the p-wave Feshbach molecule. The analytic model diverges as r → 0; so we

choose a cut off radius of 35a0 , such that the model and the full calculation have similar

ro values at large detuning. We show ro obtained from the analytic model as a dashed

brown line in figure 2.4. Note that even as the detuning becomes small (δB ≈ 5 mG) the

size of the open channels remains quite small, ro < 200a0 . Additionally, p-wave moleucules

are closed-channel dominated (Z ∼ 0.8), and rc ≈ 40a0 is constant for all δB. The small

size of the open channel, combined with the closed-channel character of p-wave molecules,

p

results in rmol

< 70a0 , which is much smaller than typical s-wave Feshbach molecules.

20

CHAPTER 2. INTERACTIONS IN AN ULTRACOLD GAS

Chapter 3

Quantum degenerate Fermi gases

At the densities and low temperatures we achieve in our experiments quantum statistics

becomes crucial. This chapter introduces quantum statistics and many-body properties of

ultracold Fermi gases. There are many excellent textbooks and review articles available

on this topic for further reading, e.g. [Pet01, Pit03, Gio07].

3.1

Introduction

At high temperatures a gas of indistinguishable particles can be described by classical

Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics. Here, the mean occupation number f (ǫν ) of the single

particle state ν is much smaller than one. As the gas is cooled down f (ǫν ) increases for

the low lying energy states. The indistinguishability of identical particles becomes crucial

when the phase space density

D = nλ3dB

(3.1)

approaches unity. Here, n is the density of the identical particles and

λdB =

s

2π~2

mkB T

(3.2)

is the thermal de Broglie wavelength which represents the spread of the atomic wave

function. Depending on the spin of the identical particles either Fermi-Dirac or BoseEinstein statistics describes the gas accurately.

21

22

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM DEGENERATE FERMI GASES

nλ3dB ≪ 1

nλ3dB & 1

T =0

Bose-Einstein

Fermi-Dirac

Figure 3.1: We compare a gas of identical bosons and fermions, respectively, at different

temperatures. At sufficiently high temperatures (nλ3dB ≪ 1) quantum statistics is negligible

because the mean occupation number for all states is much less than one. However, as the

phase space density approaches unity the statistics becomes crucial. A gas of identical

bosons begins to occupy the ground state macroscopically for nλ3dB & 1 , whereas fermions

fill up the low lying energy states with at most one atom per state. At T = 0 all bosons are

condensed in the ground state and the fermions fill up all states up to the Fermi energy.

The mean occupation number for the three different cases are

1

exp[(ǫν − µ)/kB T ]

1

f BE (ǫν ) =

exp[(ǫν − µ)/kB T ] − 1

1

.

f FD (ǫν ) =

exp[(ǫν − µ)/kB T ] + 1

f MB (ǫν ) =

Maxwell-Boltzmann:

Bose-Einstein:

Fermi-Dirac:

(3.3)

(3.4)

(3.5)

The chemical potential µ is given by the normalisation condition

X

f (ǫν ) = Ntotal ,

(3.6)

ν

where Ntotal is the total number of particles and the sum is taken over all single particle

states. From equation 3.5 it follows that the mean occupation number for fermions f FD can

23

3.2. IDEAL FERMI GAS IN A HARMONIC TRAP

not exceed one. This agrees with Pauli’s exclusion principle which states that two identical

fermions can not occupy the same state. At T = 0 the fermions fill up all states up to the

so-called Fermi energy with exactly one atom per state. The situation is fundamentally

different for identical bosons which can multiply occupy the same state. This leads, at cold

enough temperatures, to a macroscopic occupation of the ground state. This phenomenon

is well known under the expression Bose-Einstein condensation and will be discussed in

section 3.3.1. Firstly, we will turn our attention towards degenerate fermions.

3.2

Ideal Fermi gas in a harmonic trap

In our experiments the gas is typically confined in an approximate harmonic trap with

potential

1

1

1

V (r) = mωx2 x2 + mωy2 y 2 + mωz2 z 2 .

(3.7)

2

2

2

A semi-classical approach, which is valid if kB T ≫ ~ωi , replaces summations - such as in

equation 3.6 - by integrals. The density of states in a harmonic trap is then given by

g(ǫ) =

ǫ2

,

2(~ω)3

(3.8)

where ω = (ωx ωy ωz )1/3 is the geometric mean of the three trapping frequencies ωx , ωy and

ωz . The normalisation condition that fixes the chemical potential is consequently

Z

N = g(ǫ) f FD (ǫ) dǫ.

(3.9)

For T = 0 the mean occupation number f (ǫ) is a step function. It is unity up to an energy

EF = µ(T = 0) which is called the Fermi energy and zero for energies above. In a harmonic

trap the Fermi energy EF is

EF = ~ω(6N)1/3 = kB TF = kB × 188

ω/2π N 1/3

nK.

100 Hz 104

(3.10)

In the second last step we converted the Fermi energy into the Fermi temperature. Commonly used is also the definition of the Fermi wave number

kF =

where m is the mass of the atom.

p

2mEF /~2 ,

(3.11)

24

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM DEGENERATE FERMI GASES

Thomas-Fermi approximation

The density and momentum distribution of trapped gases is often calculated using the

semi-classical Thomas-Fermi approximation which assumes that locally the trapped gas

can be described by a uniform gas. In this approximation, the quantum states are labeled

by the continuous parameters position r and momentum p. The Fermi-Dirac distribution

is thus

1

.

+ Vext (r) − µ)/kB T ] + 1

Similarly to above, the chemical potential is obtained by normalising

Z

1

dr dp f FD (r, p),

N=

3

(2π~)

f FD (r, p) =

where

1

(2π~)3

exp[(p2 /2m

(3.12)

(3.13)

is the density of states. In the Thomas-Fermi approximation a local Fermi

wave vector kF (r) is defined for each point in space by

~2 kF2 (r)

+ V (r) = EF .

2m

(3.14)

This implies that the chemical potential is equal in space which is fulfilled in an equilibrium

as we would have a net flux of particles otherwise. For a fermionic gas at T =0 all momentum

states at position r are occupied up to ~kF (r). It follows that atoms further away from the

centre of the trap have smaller momenta. The number of atoms that fit into the momentum

sphere with radius ~kF (r) multiplied by the density of states yields the density at position

r

1

4

.

(3.15)

n(r) = π(~kF (r))3

3

(2π~)3

Combining equations 3.14 and 3.15 gives the density distribution for V (r) < EF yields

i3/2

1 h 2m

n(r, T = 0) = 2 2 EF − V (r)

.

(3.16)

6π ~

For V (r) > EF the density distribution vanishes. From this we also obtain the maximum

extent of the fermionic cloud RFi in direction i = x, y, z by setting V (RFi ) = EF

s

r

1/6 ω

2kB TF

~

i

i

RF =

or

RF =

48N

.

2

mωi

mω

ωi

The density profile (equation 3.16) then reads

h

x 2 y 2 z 2 i3/2

8N

n(r, T = 0) = 2 x y z 1 −

−

.

−

π RF RF RF

RFx

RFy

RFz

(3.17)

(3.18)

25

3.3. PAIRING AND SUPERFLUIDITY

The momentum distribution ñ(p) can be calculated similarly using the equivalent equations yielding

ñ(p) =

8N (p/~)2 1

−

.

π 2 kF3

kF2

(3.19)

The density and momentum distribution presented here are only exact for T=0. The

expressions for finite temperature can be found in [Geh03], for example.

3.3

Pairing and superfluidity

In 1995, the observation of Bose-Einstein condensation and hence superfluidity of bosonic

atoms was an amazing breakthrough in cold matter physics [And95, Dav95, Bra95]. Due

to the Fermi exclusion principle this phase transition is not possible for fermions. However,

pairing of fermionic atoms can lead to bosonic systems for which such a superfluid phase

transition is possible. Close to a Feshbach resonance, in particular, pairing may lead to

molecules for repulsive attraction and long range Cooper pairs for attractive interaction.

The region between both regimes is called the BEC-BCS crossover. In the following, we

shall discuss all three regions while special emphasis is laid on molecular Bose-Einstein

condensation as this is most relevant for our experiments.

3.3.1

Bose-Einstein condensation

As discussed in section 3.1 each quantum state can at most be occupied once in a gas of

indistinguishable fermions. In contrast, the bosonic mean particle distribution f BE (ǫν ) can

be greater than one. In particular, the population of the ground state ǫ = 0 can become

arbitrarily large for µ = 0 as T → 0. For a temperature below a critical temperature TC

the normalisation condition

N=

Z

g(ǫ) f BE(ǫ) dǫ

(3.20)

can only be fulfilled for an unphysical positive chemical potential. To fulfill the normalisation condition below the critical temperature a macroscopic fraction of bosons occupy the

ground state. The number of thermal particles NT is given by the normalisation condition

and the population of the ground state is thus N BEC = N − NT .

In a harmonic trap the critical temperature and condensate fraction for a non-interacting

26

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM DEGENERATE FERMI GASES

Bose gas are given by

TC = 0.94~ωN 1/3 /kB

T 3

N BEC

= 1−

.

N

TC

(3.21)

(3.22)

All condensed particles occupy the ground state of the harmonic oscillator with wave

function φ0 (r). Thus, the density distribution of the condensate is given by nBEC (r) =

N BEC |φ0 (r)|2 . The geometric average of the width of the wave function φ0 (r)

aho =

~ 1/2

mω

(3.23)

is much narrower than the corresponding width of the thermal cloud. From this it follows

that the density distribution of the condensed part can easily be distinguished from the

thermal cloud by its narrow peak.

Interacting condensates

For non-interacting Bose-Einstein condensates the density distribution n(r) is proportional

to the single-particle density distribution. This is no longer true for interacting condensates. In principle, the many-body wave function of a Bose-Einstein condensate can be

found exactly by solving the many-body Schrödinger equation. However, this is rarely

practical as it requires enormous computer power even for fairly low particle numbers. Instead, interactions are often treated as a mean field potential g |n(r, t)|, where the coupling

constant g is given by g = 4π~2 a/m. This leads to a non-linear equation for the order

parameter (or condensate wave function) Ψ(r, t) [Pit61, Gro61]

i~

~2 2

∂

Ψ(r, t) = −

∇ + Vext (r) + g |Ψ(r, t)|2 Ψ(r, t)

∂t

2m

(3.24)

from which the density distribution can be calculated by n(r, t) = |Ψ(r, t)|2 .

This so-called Gross-Pitaevskii equation resembles a non-linear Schrödinger equation

and describes the macroscopic structure of the condensate for N ≫ 1 and T = 0. A

condensate in equilibrium is described by the time-independent Gross-Pitaevskii equation

~2 2

2

−

∇ + Vext (r) + g |Ψ(r)| Ψ(r) = µΨ(r),

2m

(3.25)

27

3.3. PAIRING AND SUPERFLUIDITY

where µ is the chemical potential. If the mean field energy dominates, which is often the

case, the kinetic energy term can be neglected . In this Thomas-Fermi approximation the

density distribution is given analytically by

1

n(r) = (µ − Vext (r)).

g

The chemical potential µ is determined by the normalising condition

yields

(3.26)

R

dr n(r) = N and

~ω 15Na 2/5

µ=

.

(3.27)

2

aho

The shape of the density distribution is an inverted parabola where the density goes to

zero at the Thomas Fermi radius

Ri = aho

15Na 1/5 ω

aho

ωi

.

(3.28)

We see that the shape of a Bose-Einstein condensate is very similar to the Fermi profile

(equation 3.16 and 3.17) with the main difference being the dependence of the radii on the

particle number N. In the case of identical fermions interactions can be neglected because

the quantum pressure term dominates.

The finite temperature generalisation is straightforward for non-interacting clouds as

the thermal and condensed parts can be treated separately. In interacting clouds the two

components are coupled by the interaction term. However, the coupling between both

components can often be ignored as the density of the thermal cloud is usually much lower

than the density of the condensed component. Hence, in this limit the condensed cloud

can be described by the T = 0 solution where the particle number N is replaced by the

number of condensed particles N0 .

In a cloud with repulsive interaction (a > 0) the peak density is lowered compared to a

non-interacting cloud (see equation 3.26). The reduced peak density leads to a reduction

of the critical temperature TC . The shift compared to the critical temperature of a noninteracting gas TC0 has been calculated to be [Gio96]

TC − TC0

a

.

= −1.32N 1/6

0

TC

aho

(3.29)

Below TC the number of condensed particles is also reduced due to repulsive interactions. Perturbatively, the condensate fraction has been found to be [Nar98]

T 3

T 3 2/5

N

ζ(2) T 2 =1−

1−

−η

N0

TC0

ζ(3) TC0

TC0

(3.30)

28

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM DEGENERATE FERMI GASES

where ζ(2)/ζ(3) ≈ 1.37 and

η=

2/5

µ(T = 0)

1/6 a

≈

1.57

N

kB TC0

aho

(3.31)

is a scaling parameter.

3.3.2

The BCS regime and the BEC-BCS crossover

For completeness of this dissertation, we briefly introduce the BCS state and the BEC-BCS

crossover. Although our system allows to explore the crossover we have focussed on other

experiments during the time of my studies.

3.3.2.1

The BCS regime

A fermionic gas with weakly attractive interactions kF |a| ≪ 1 can undergo a phase transition into a superfluid phase at low enough temperatures. This is accompanied by the

formation of long range Cooper pairs [Coo56] which consist of two attractive fermions in

two different spin states which are correlated in momentum space rather than in real space.

In contrast to the formation of molecules, Cooper pairing is a many-body phenomenon relying on the presence of the “Fermi sea”. The size of the pairs is typically much larger

than the mean particle spacing n−1/3 , so that the pairs overlap [Tin66, Hou97].

In metals, the macroscopic formation of Cooper pairs of two electrons with opposite

spin gives rise to superconductivity. In 1957, this phenomenon led to the development of

a novel theory by Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer (BCS) [Bar57]. An introduction to the

theory of superconductivity is given in [Tin66].

Of particular interest is the critical temperature at which the phase transition occurs.

In terms of the Fermi temperature this is given by [Gor61]

kB TC ≈ 0.28EF exp −

π

2kF |a|

.

(3.32)

In the BCS limit the critical temperature is well below the Fermi temperature and already

for kF a = −0.2 we have TC = 10−4 TF which is experimentally unfeasible with current

set-ups using cold atoms.

The spatial density profile can be approximated in the Thomas-Fermi limit for kF |a| ≪ 1

(BCS limit). The energy of atoms in state |↑i shifts due to interactions by gn↓ where

29

3.3. PAIRING AND SUPERFLUIDITY

g = 4π~2 a/m is the coupling constant and n↓ is the density of atoms in state |↓i. The

density distribution (equation 3.16) then reads

i3/2

1 h 2m

.

n↑ (r) = 2 2 (EF↑ − V (r) − gn↓ )

6π ~

(3.33)

This can be greatly simplified assuming an equal spin mixture (n(↑) = n(↓) = n). The

attractive interaction in the BCS regime thus compresses the cloud. To first order perturbation theory, the Fermi radius reduces to [Gio07] (note a < 0)

RFint = RF0 1 +

256 0 k a

315π 2 F

(3.34)

where RF0 and kF0 are the Fermi radius and Fermi wave vector of the non-interacting gas,

respectively.

3.3.2.2

BEC-BCS crossover and unitarity

We have introduced molecular Bose-Einstein condensation and the Bardeen-CooperSchrieffer state of long-range Cooper pairs. These two form the two extremes of the BECBCS crossover which has recently been studied in several laboratories utilising Feshbach

resonances [Reg04b, Zwi04, Chi04a, Bar04b, Bou04, Kin04a, Par05]. The crossover is

characterised by a smooth transition from bosonic to fermionic behaviour of the gas. A

theoretical treatment of the underlying physics can be found, for example, in [Che05a].

Close to the Feshbach resonance the scattering length and hence the size of the weakly

bound Feshbach molecule can exceed the interparticle separation. In this regime the physics

becomes universal, depending only on the interparticle separation n1/3 and the Fermi energy

EF . In the unitarity limit (kF |a| → ∞) the scattering cross section σ0 (k) = 4π/k 2 (see

equation 2.15) is independent of the scattering length. Thus, the mean-field shift no longer

depends on the scattering length and is instead proportional to the Fermi energy

g = βEF .

(3.35)

The dimensionless proportionality factor β is universal to all Fermi gases at unitarity.

It has been measured in fermionic gases of both lithium [Tho05a, Par06a, Tar07] and

potassium [Ste06] yielding β ∼ −0.58. The shape of the trapped gas becomes equivalent

to the one of a non-interacting system. However, due to interactions the Fermi radius

reduces to [Gio07]

RFunitarity = (1 + β)0.25 RF0 .

(3.36)

30

CHAPTER 3. QUANTUM DEGENERATE FERMI GASES

3.3.3

p-wave superfluids

In section 2.4 we discussed the formation of p-wave molecules. Being composite bosons a

gas of p-wave molecules can, at least in principle, form a Bose-Einstein condensate. To

date such a superfluid has not been realised and remains one of the big challenges in

the field of cold atom physics. There are many properties that make p-wave condensates

an important object to study. Such gases display a BEC to BCS superfluid crossover

and a complex phase diagram with phase transitions between different projections of the

angular momentum [Bot05, Che05b, Gur05, Isk06]. These condensates may also give a

link with other pairing phenomena such as d-wave high-TC superconductors [Tsu00] and

liquid 3 He [Lee97]. Higher-order partial wave Feshbach resonances are intrinsically narrow,

because the interacting atoms have to tunnel through the centrifugal barrier before they can

interact with each other. This narrowness allows arbitrarily exact theoretical calculations

in the low collision energy limit [Gur07].

It is also interesting to consider what implications the molecular size (section 2.4) has for

the realisation of a BEC-BCS crossover regime for nonzero orbital angular momentum pairing. The crossover regime for s-wave pairs is comparatively smooth because the molecular

size grows appreciably as the detuning approaches zero from below. However, for p-wave

pairs the crossover will be much more abrupt as the molecular size barely changes at the

resonance. Additionally, on the BCS side of a p-wave resonance, the pair wavefunction may

have significant amplitude at short range because of the centrifugal barrier. We also expect

an increase in the rate of inelastic vibrational quenching collisions between molecules and

free atoms which release large amounts of energy and lead to rapid loss. Fermionic particle

statistics greatly suppresses this process for weakly bound s-wave molecules comprised of

two fermions [Pet04]. However, near a p-wave Feshbach resonance, fermions in the same