* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Hearing loss is one of Australia`s most common forms of impairment

Survey

Document related concepts

Sound localization wikipedia , lookup

Olivocochlear system wikipedia , lookup

Telecommunications relay service wikipedia , lookup

Evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles wikipedia , lookup

Auditory system wikipedia , lookup

Lip reading wikipedia , lookup

Hearing aid wikipedia , lookup

Hearing loss wikipedia , lookup

Sensorineural hearing loss wikipedia , lookup

Noise-induced hearing loss wikipedia , lookup

Audiology and hearing health professionals in developed and developing countries wikipedia , lookup

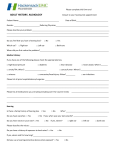

Transcript

Hearing loss is one of Australia’s most common forms of impairment (Wilson et al. 1999) yet it is considerably under diagnosed (Chung, Des Roches, Meunier, & Eavey, 2005). Though the gold standard for measuring hearing loss is a full audiological examination, hearing loss can also be measured cheaply and efficiently with pen and paper tests (see Coren, & Hakstian, 1992). However, there are no tests yet of this type which measure both hearing loss, risk factor for potential hearing loss, and attitudes to hearing loss and protection, all of which may influence one’s need for further testing and/or treatment. The present study aimed to develop and validate a simple questionnaire type test to be which could be used to clinically evaluate test takers, taking into account not only their existing hearing loss, but their risk factors for potential damage, and their attitudes towards hearing health and hearing protection. This may be of particular benefit to a younger generation, who have been shown to have a variety of psychosocial motives underlying their attitude towards hearing health issues (see Bohlin, Sorbring, Widén, & Erlandsson, 2011; Bohlin, & Erlandsson, 2007). In terms of occupational hearing loss, Australian businesses and industry is held to a high standard (see Safe Work Australia, 2004). This awareness and use of hearing protection strategies is rigorously audited and enforced by governing bodies, ensuring that employees are well cared for in their workplace. However, exposure to high noise levels in non-professional environments such as home renovation, hunting, playing in a musical group, automotive repair, use of petrol engine driven gardening tools and spectating aviation, car and motorcycle events, can often be as damaging as occupational exposure and are often done with no hearing protection (Daniel, 2007; Neitzal, Gershon, McAlexander, Magda, & Pearson, 2012). In addition to this increase of harmful recreational noise exposure, there are many who are unaware of the health risks associated with these seemingly harmless activities (Danhauer et al., 2012). It appears that there is a lack of knowledge regarding hearing health in the non-professional industry. Additionally, young people who frequent concerts and night clubs may expose themselves to dangerously high levels of noise, and perhaps more importantly, are less likely to use hearing protection (Bogoch, House, & Kudla, 2005; Widén, Holmes, Johnson, Bohlin, & Erlandsson 2009). Moreover, with the proliferation of personal media devices, opportunity for exposure has increased dramatically and has become a primary source of noise exposure (Neitzal, et al., 2012), particularly amongst young people (for review, see Vogel, Brug, Ploeg, & Raat, 2007). With greater opportunity for noise exposure, in both an important aspect of potential risk for hearing loss is behaviours and attitudes towards hearing health (Vogel, et al., 2007). An association has been drawn between risk taking behaviours, and an increased likelihood of engaging in activities which are detrimental to hearing health in a population of 15-20 year olds (Bohlin, and Erlandsson, 2007). Young people are apt to expose themselves to high risk environments, and are also less likely to use hearing protection. (Bohlin, and Erlandsson (2007) highlight that any measure of hearing loss in a young population should take into account their attitudes towards hearing loss and its social impact. However, a survey conducted by Australian Hearing (2008) suggests that attitudes towards hearing loss and hearing protection tend to increase in safety as one gets older. The sense of hearing is derived from converting mechanical pressure in the air to nerve signals to the brain via hair like cilia in the inner ear. This begins with air pressure entering the ear canal and arriving at the eardrum, from here the sound waves against the ear drum are transduced through several bones in the middle ear where it then arrives at the cochlea, the inner ear. Waves in the fluid of the inner ear stimulate cilia, hair chasped cells which respond to different frequencies. This movement is passed to the auditory nerve and to the brain, providing the sense of hearing. However, prolonged exposure to loud noise damages the hair cells in the cochlea, such that they are no longer able to effectively communicate information to the brain (Kalat, 2002). Sound pressure level is measured in decibels (dB), this coefficient of sound pressure level is a logarithmic scale, and each additional 20dB is a 10-fold increase in sound pressure level (Goldstein, 2002). Damage to the hair cells in the inner ear is caused by a combination of amplitude of sound pressure levels and the duration of exposure to the noise (Kalat 2002). An increase in either of these factors will increase the damage to hearing, in some cases leading to irreversible hearing loss where there is permanent death of hair cells in the inner ear. For example, permanent hearing loss can occur following use of a lawn mower (90dB approx) for two hours, however, being in a nightclub (>100 dB) can lead to permanent hearing damage in less than 15 minutes (values taken from National Acoustic Laboratories, 1983). Moreover, the hair cells in the inner ear are frequency specific, and as such, there is often loss of specific frequencies in hearing, rather than a global deficit Though the gold standard for detecting hearing loss is a full audiological assessment, it requires more effort than a simple questionnaire which can be cheaply administered by either a GP or self-report. Thus, a questionnaire may prove to have a greater reach in terms of the general population. While it would be possible to produce more exhaustive assessment of all factors which relate to exposure to noise and risk activities, it was considered to be important to develop a test which could be easily scored and accessed, and did not place undue time demands on those taking part. In the broader context, this test should be of benefit to the Australian community through a larger number people assessed for hearing loss, and a greater level of awareness of the permanent nature of exposure related hearing loss. The test being simple to administer and score may lead to more false positives than a more complex and longer test, but as it is the intention to have all positive test results re-assessed by a full audiological exam, it was deemed prudent, and in the best interests of all participants to allow this. Subjective measures of existing hearing loss have been shown to be valid when compared with objective audiometric assessment. Coren, and Hakstian (1992) developed a 12 item scale which measures existing hearing loss. This scale was shown to have an especially high level of validity in terms of its correlation with objective audiology measurement (r = .81). And as such, the present scale takes into account the methodology used in the HSI. Other scales which have investigated factors relating to hearing loss include the Youth Attitudes to Noise Scale (YANS, Olsen, & Erlandsson, 2004), this scale measured factors which contribute to how young people perceive hearing protection, hearing health, and psychosocial factors. However, existing hearing loss questionnaires do not adequately and concurrently measure both existing hearing loss, and risk factors relating to hearing loss, and as such appear to be limited in their clinical relevance. Hence, with an aim for clinical utility, the present study aimed to develop a scale which measures existing hearing loss, and attitudes such as thrill seeking behaviour, and attitudes towards hearing protection in the general Australian population. Combating the reluctance of participants to reveal hearing loss due to the social undesirability of disability is the primary justification of providing a new scale.