* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download - University of Alberta

Molecular ecology wikipedia , lookup

Occupancy–abundance relationship wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

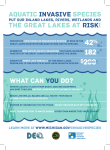

Introduced species wikipedia , lookup

Island restoration wikipedia , lookup

Fauna of Africa wikipedia , lookup

Latitudinal gradients in species diversity wikipedia , lookup