* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Perfect competition wikipedia , lookup

Darknet market wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

Service parts pricing wikipedia , lookup

Grey market wikipedia , lookup

Market penetration wikipedia , lookup

Dumping (pricing policy) wikipedia , lookup

Segmenting-targeting-positioning wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

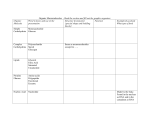

DISTRIBUTION IN THE ONTARIAN ORGANIC FOOD MARKET: TRENDS AND CHALLENGES1 Abstract The organic market is the fastest growing sector in the food industry. However, there are some unique challenges to the cost and logistics of moving locally or regionally produced organic food to the market. Among other factors, production methods and operations size are key. The main objective is to determine the factors on which the different production methods and distribution systems rely on in order to add value to the organic food products offered. Findings highlight for the different production methods and distribution systems in place: (1) the main current trends, (2) the strategies and practices used to add value to their offer, and (3) the challenges they are facing in the actual organic food market. 1 The authors would like to thank the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food and the Ministry of Rural Affairs for providing financial support. 1 INTRODUCTION Nowadays, research on environmentally and sustainable consumption describes the problems with current marketing and consumption practices (Prothero et al., 2011). Most environmental challenges that humanity is facing relate to unsustainable consumption patterns and lifestyles. This is also related to basic needs such as food. The present food chain is mainly based on food scarcity, GMOs, use of pesticides, and industrialization of the agricultural system. Organic agriculture and OF consumption are now going mainstream (Tutunjian, 2008). It is now recognized that agri-food markets have changed, mainly due to a number of food scares and crises that have stimulated change in demand for higher levels of safety and quality in food. The organic market is the fastest growing sector in the food industry and double-digit market growth rates are leading to undersupply in various regions (Organic Monitor, 2007). However, there are some unique challenges to the cost and logistics of moving locally or regionally produced OF to the market. Of particular interest are the operations size and the situation of small and medium size farms. The production of the latter is of little interest to mainstream grocery chains, as it is limited to a few hundred tons. Among other factors, production methods and operations size are key here. Large-scale farming is sustained by important economies of scale while small scale farming leads to higher prices to cover extra costs of not using fertilizers and antibiotics. As a result, there is a wide variety of product classifications depending on the production methods and thus, the operations’ size. This in turn gives raise to 2 distinct distribution systems: long channels, eg. retail chains, that add value through price and high distribution intensity, and short channels, eg. direct from producers, that add value through their production methods and sustainable practices. Hence, discrepancies between market realities, the value chain and the value delivery system are still a challenge for the OF sector. The main objective of this research is to determine the factors on which the different production methods and distribution systems rely on in order to add value to the OF products offered. To address this issue, this study first presents the current literature related to the structure of the production and distribution of the OF system and market, supported by an integrative production-distribution model. THE ORGANIC SYSTEM The Ontarian Organic System According to the Canadian General Standards Board, "Organic production is a holistic system designed to optimize the productivity and fitness of diverse communities within the agroecosystem, including soil organisms, plants, livestock and people. The principal goal of organic production is to develop enterprises that are sustainable and harmonious with the environment." (Canadian General Standards Board, June 2011) It is worth noting that the organic movement, which began as an alternative style of production among small farms looking both to reduce their environmental footprint and to differentiate their products from commercially produced foods, has been admitted to the mainstream market. Certification, which came about to prevent fraudulent claims, has enabled large players to get into the game, facilitating the long-distance shipping and distribution of organic products required to bring them to grocery stores and wholesale clubs and applying within the value chain the same downward pressure on price exhibited in the conventional food value chain. This has resulted, for some small farmers concerned with the philosophical aspects of organic production, in diminished credibility of the organic standard and a refusal to participate. It has also hardened the value chain against entry by these small farmers. 2 Use of the term "organic" is restricted in Canada to farms, products, processors and other intermediaries in the value chain between production and consumption that have been certified by a Certifying Body like QAI, ProCert or EcoCert. Labels like "local," "natural," "pesticide-free" and "ecologically friendly" are not regulated and tend to be used by small farms catering to local or regional clientele. With the exception of marketing board-regulated products like dairy or chicken, production and handling of foods sold under these labels is for the most part not monitored or regulated except by provincial agencies and district health units. This is done only in terms of health/safety inspections and only as required by law (Hamzaoui et al., 2013). "Transitional organic" is also a restricted label and describes farms that have made the commitment to move toward organic certification. Organic Farming Operations There seems to be little overlap between large, medium and small producers at the processing, distribution and sales stages. There is very little shared infrastructure between these levels. The processing and distribution system for large producers is, for the most part, closed: it's available to those large producers only. The system for the medium-sized producers, developed by those same medium-sized producers, tends to remain closed because they are still struggling to maintain their position. Often, these producers consider the information and infrastructure they've developed to be proprietary (Hamzaoui et al, 2013). By characterizing producers' use of the value chain to get products to the consumer we can break the mass of Ontario organic producers down into three categories: large, small and medium-sized operations. Large producers are characterized by organic cash crops, which are either exported or processed after they leave the farm, or by livestock or field crops that are most likely to go to distributors and processors for further treatment (Hall, Mogyorody, 2001). Like the mediumsized farming/processing operations, larger processing and distribution centers tend to copack with conventional products, ensuring sufficient throughput to be profitable. Medium-sized producers tend to produce for a smaller geographical market (Hall, Mogyorody, 2001). Limited by infrastructure, some of these producers are now working together to develop their own, partnering up with complementary business to be able to expand the offerings of their on-farm markets to attract more customers. Others have partnered with small regional processor/distributors to reach restaurants and specialty food retailers. Small organic producers tend to not use distribution intermediaries. Instead they focus on direct relationships with consumers through farmers' markets and on-farm markets. They may supply some restaurants, specialty retailers, and small grocers, but these relationships are painstakingly developed and rely on niche marketing and personal relationships. Smaller packing, processing and distribution operations are often spawned by the producers themselves as a way of making their product more marketable, adding value and extending the selling window for their own products; basically building in forward integration of the value chain. Organic Value Chain in Ontario OF products are sold through a variety of outlets including mainstream supermarkets, natural food and health stores, small grocers, warehouse clubs and drug stores (cf. Figure 1). Entry into the market of large supermarket chains has had a significant impact on price, producing downward pressure on the value chain in much the same way it has occurred in the conventional chain. While this has made organics more accessible and increased the volume of sales, the return to a focus on price has decreased the value of the organic label to small farmers. 3 Figure 1: Value Accumulation Through the Distribution Chain Market Distribution Channels Since organic products have entered into the mainstream/conventional market, a similar mainstream value chain has developed for organic products being sold through conventional outlets. Further, in conventional food systems there exists between producers and consumers of food products a series of handlers involved in the processing and distribution at various stages of the delivery from farm to plate. The distribution of sales volumes seems to be related to the structure of the distribution systems in place and to the following two main trends of consumption: (i) regular OF consumers using standard distribution channels (supermarkets) and (ii) hardcore consumers adopting alternative channels (box delivery, farmers’ market, specialty stores, and small grocery stores). Conventional distribution channels, characterized by a longer channel where consumers do not see and interact with the producer and where the information about food is limited, is targeted toward consumers that look for a one-stop grocery shopping experience (Hamzaoui-Essoussi and Zahaf, 2009). On the other hand, direct channels such as the farmer’s market is targeted toward consumers that look to interact with the producers (Smithers et al., 2008), ask questions about their production methods, food origin and variety, and cooking tips. METHODOLOGY Rationale and Objectives This study aims at providing (i) a detailed assessment of the actual situation in the OF distribution system, i.e., superstores, specialty stores, and farmers’ market; and (ii) an understanding of the value delivery network importance in creating value added to the OF supply. In order to address these objectives, this research is based on the perspective of the members of the distribution channels regarding their perception of the current organic market situation and the distribution system. This approach allows to pinpoint all supply side factors that may affect the value creation in the current value chain. Primary data was collected through personal interviews with OF producers, market intermediaries and final retailers in 6 Ontarian cities: Thunder Bay, Toronto, Ottawa, Guelph, Barrie, Kitchener, and Kingston. 4 Procedure In-depth interviews have been conducted with store managers of retail chains (superstores), specialty stores, small groceries, and farmers’ markets and producers. Five store managers were randomly selected and interviewed in each city, for a total of 35 in depth interviews. Interviews were based on an interview guide and lasted about 45 minutes to 1 hour. The guide probed store managers to discuss the current OF market, the actual structure of their distribution channel, their marketing strategies and actual challenges. Interviews were recorded (digital voice recorder), transcribed, and coded by the researchers using content analysis. Data was organized around particular themes that were coded and categorized in order to facilitate their interpretation. Two separate researchers coded the data to insure consistency (cf. Kassarjian, 1977). The inter-judge consistency was above the minima required level of 80%. Six main themes emerged from the interviews: (i) the OF market trends, (ii) importance of country of origin when selecting OF products, (iii) distribution of local, regional, national, or imported OF products, (iv) important changes in OF product distribution, (v) value building through channel of distribution, and (vi) main challenges distributors will be facing. The analysis of the interviews is presented by combining these themes to the type of OF distributors. RESULTS The Organic Food Market Trends The overall impression of the evolution of the OF market in Ontario from all the interviewees is that the market is growing. Results also highlight an overall trend of increasing level of consumers’ confidence in the OF products. From the producers and farmers’ market perspective, although the market is generally growing, two specific trends are mentioned: (1) most of growth is in highly processed packaged products (frozen, ready to eat meals, etc.), and (2) growth is also noticeable in the wholesale arena (on both the local and organic front), including institutional, large scale grocery stores, restaurant chains, etc. One producer mentions as an example President Choice organics, or Simplicity brands from Metro, “that has taken away from the local farmer because the supply chain is now going through warehousing”. Another interesting point is related to the size of the farms and their output: farmers that are not huge and not into factory production, are somehow struggling and working to maintain the integrity of what they do. This is confirmed by one farmer mentioning that “the world of organic gets diluted by capitalist interest basically”. In other words, there is a trend of having on one side the small size farmers that are into organic because of the values they believe in (the soil, the environment, the animal welfare, etc.), and thus considering themselves as “philosophical organic” versus bigger players that entered the market because of potential business, and thus considered as “commercially organic”. From the distributors’ perspective, the OF market is growing at a substantial rate, and the demand for organic and local is out there. People are learning and wanting to know where their food comes from because they are scared about GMOs, pesticides and chemicals, especially for their kids. Thus, they expect this market to continue to grow. The market is indeed growing due to greater health conscious options, and demographics that has just come through school, and that have the buying power now, having kids, and being really conscious about what they are feeding their kids. From the perspective of specialty stores, OF has gained a much larger mainstream appeal to the point that most of the regular grocery chains (Loblaws, Farmboy, etc.) are now carrying organic produce and food: “mainstream grocery stores also really picked up on the organic since 5 years”. There is also a lot more variety offered. Market growth is also linked to 5 organic that still has a lot of strength in the name, but outside the core consumers, there is a lot of fuzziness about what organic really means and people will trade names in and out of that (fair trade/natural/ecologically grown). One of the most significant trends is that it seems like local has replaced organic as being the “in” thing. One manager says: “Local is the “new black” for sure”, and “many people are just as happy to buy locally conventionally produced something, rather than an organic certified one”. From the small grocery stores’ perspective, there are also three main trends: (1) people are much more into local, (2) people are more into packaged products (prepared food), and (3) big chains and imports appeared. For one interviewee, “In the 1970s all beans were local, and then big food chains showed up as well as more products from China, and local farmers were put out from business”. From the retail chains’ perspective, the market is pretty much the same and evolves around the same offering. There is a lack of knowledge among consumers about what organic is and how it differs from natural, but overall, the market is growing. Importance of Country of Origin From the producers and farmers’ market perspective, country of origin of the products is very important: some give a lot of importance to bring only local products, some are putting their bigger effort into marketing things that are grown within reasonable distance, and if not available, they will look to neighboring provinces first, then to other countries. A very strong trend that was noticed is a real distrust in Chinese OF even though it is certified organic, as they consider China as the uncontrolled unknown. From the distributors’ perspective, country of origin seems pretty important also for their consumers: “one of the sales point is that the vegetables are local”, “when it is coming from overseas, they are less interested”. For dairy products, country of origin is very important. Overall, distributors make sure that it is at least North American. From the perspective of specialty stores, country of origin is also very important and first choice always goes to local organic, Ontario Organic or cross-Canada organic. The vision of the Ontario Natural Food Co-op, “Living in a sustainable world from seed to plate”, makes them want to carry operations as much close to where people live as possible. In other words, the value chain can be very local and very close to the grower; the processor or the grower could be the processor and the distributor in a really localized food system. On the other side, there are global value chains that can be incredibly complex, and food can travel thousand of kilometers with many stops along their way. The importance attributed to country of origin is also driven by a lot of customers who ask where things come from, and who like to try to operate in a 100 miles radius: “they want organic they also want local but sometimes you can’t get both”. In any case, there is a country where customers don’t want to buy from, China. Last, country of origin is not very important during the winter months. From the small grocery stores’ perspective, country of origin is important because people ask for it. In winter, stores buy foods that are US grown, sometimes they take what they can get. Most stores would never sell Chinese OF, even certified! In the last couple of years, local – and local organic - has been quite popular as well: “a lot of customers who ask where things came from and a lot of customers that want to try as much as they can to operate within a 100-mile radius. They want organic, they also want local”. From the retail chains’ perspective, the same importance is attributed to country of origin. As far as meat goes, retailers offer only Ontarian products. Everything else is always local, and only to the extent that they cannot get local then they will get from outside of the country. Some retailers narrow it down to stay within North America. 6 Organic Food Distribution From the producers and farmers’ market perspective, an important trend in OF distribution is that it is becoming more centralized: “bigger players buying smaller companies and it continues to be that way!” More supermarkets are carying organic products. About ten years ago, buying OF was limited to few places whereas now they are available at most food place, food selling places, especially the bigger supermarkets: “probably Wal-Mart even has it!” Some producers are trying to cooperatively market and assist distributors “it's not a cooperative, but it's co-operative marketing!” The door to door delivery service type model is also evolving for some farmers from traditional CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) to a mixed type of CSA. From the distributors’ perspective, the market is becoming intensively competitive. Distribution is becoming more centralized: companies have grown and become part of other distributors, as well as some distributors falling. From the perspective of specialty stores, a major trend is reported, which is the centralization of distribution. Canadian organic growers and organic farms are actually trying to do that sort of cooperative type of settings where they get access to all the farms, they bring all OF products together and then they sell it. Further, there is a consolidation going on. Now, instead of having a whole bunch of growers or farmers coming in individually to sell to stores, there is more emphasis on finding intermediaries or middle people to sell and distribute products on their behalf, such as The Ontario Natural Food Coop, Sato, or Coyote. In Southern Ontario, many of the CSA farms are using a warehouse called Fenning. From the small grocery stores’ perspective, there is an increase in the number of farmers’ markets although some of them aren’t successful. More suppliers are entering the market, which means more variety and more places of origins. This fits the demand to a certain extend. From the retail chains’ perspective, organic is available in larger chains, not to the same level of quality or quantity as everything else, but it now exists because the market is growing. Value Building Through Channel of Distribution All distributors were prompted to highlight their competitive advantages, and how they build value throughout their channel of distribution. Results are depicted in Table 1. Table 1: Competitive Advantages and Value Building per Type of Distributor Producers/ Farmers markets Distributors Specialty stores Small grocery stores Retail chains Competitive advantages Variety, Professional, Local / Canadian local, Experience, Brand, Soil, Service, Relationship, Reliability Relationship, Price Integrity, Quality, Relationship, Knowledge, Price, Transparency, Reputation Customer Service, Location, Support local, Price, Trust relationship Name, Educated staff, Service, Location, Variety, Quality Value building Variety, Community, Delivery consistency, Service, Quality, Attractive product, Supply consistency, Promotion Variety, Quality Variety, Service, Relationship, Quality, Consistency Personal Service, Variety, Quality, Freshness, Best price, Samples / trials, Experience, Knowledgeable staff, Direct contact, Variety, Price For producers and farmers’ markets, distributors and specialty stores, the price is not considered as an element for building value throughout their distribution channels. Producers 7 and farmers’ markets are also the only type of distributors not mentioning price as a competitive advantage, whereas they consider “local” as a competitive advantage, and “community” for value building. “Relationship” is one of the competitive advantages for all the types of distributors except the retail chains that consider their brand name as a competitive advantage. Current and Future Challenges of Organic Food Distributors From the producers and farmers’ market perspective, there are three main challenges: (1) centralized distribution, (2) distribution costs, and (3) pricing. The distribution system is becoming more and more centralized because bigger players are in the market and they are selling products at lower costs, so small players can't compete with the efficiencies of larger corporations. Most farmers would like to deal “with 13 little guys not with 2 big guys”. This seems to already be happening in the US. Distribution costs are perceived as being already very high, which might be sustained in the future as well as higher prices. From the distributors’ perspective, the main challenge is clearly competition as well as the availability of products. From the perspective of specialty stores, there are three main challenges: (1) price, (2) big players in the market, and (3) the impact of agribusiness on OF production. Price will still be a challenge as it is directly related to margins. There are different types of price barriers. Pricing organic products like the non-OF is still not a reality. The second challenge pertains to the risk of being co-opted by the big players. Therefore, they see that the only thing they can do is maintain brand integrity. People buy because they trust the brand and the name associated to the product. Last, competition used to be limited to a few places. With the incursion of agribusiness in OF production, now organic products are available even in large and medium retail chains. But much of the main trust of OFs seems to be from small and medium farms (often family-owned or co-op owned). From the small grocery stores’ perspective, the major challenges would be: (1) mainstream suppliers, and (2) pricing. The major challenge is linked to more mainstream suppliers carrying more organics, while small grocery stores have to attract customers to their locations in the first place “before they get to the Metro or Loblaws”. Second, the increasing costs of raw materials and food in general make managers worry about organic product prices in the future. Interestingly, one manager mentioned government interference as a potential big challenge. It is perceived to strictly regulate the industry. From the retail chains’ perspective, the challenges are similar to some of those mentioned by small grocery stores. One challenge is basically going back to educating the customer and just communicating to the customers that OF products are worth buying. The second challenge is linked obviously to government regulations. Relationship with farmers has evolved, because the government wants to have more control over how farmers’ products are handled and how they are grown. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The market for organic products is generally seen as growing and having further growth opportunities. All players from the supply side mention an increasing diversification of OF product and distribution channels. Whereas the types of distributors are mainly farmers, specialty stores, and retail chain, the increasing number of distribution channels is essentially based on more supermarkets and food store chains. These channels are widening their offer and look for more competitive prices. These trends are directly dependent on the product life cycle. The marketing of OFs is not at maturity yet, leading to a lack of market standardization. In fact, there is a clear differentiation between two distinct perspectives: long channels versus 8 short channels (cf. Error! Reference source not found. for more details). This shows the current divide in the OF supply and demand sides. Long channels strategies are convenience and price driven. They offer an organic value targeted toward a certain consumer profile; these are customers that buy organic for health reasons. Conversely, short channels are production method driven. These channels serve consumers having a principle-oriented life style; thus the environment and the support of the local economy are the main drives of this market demand. Price is not an issue here. Figure 2: Organic Foods Value Creation and Value Chain Model In other words, consumers adopting short channels (producers/farmers market and specialty stores) are clearly looking for proximity with the producer, fresh products and quality, and a better understanding of the organic farming process. This segment shows a clear interest for the impacts of the production methods on health and the environment. Conversely, consumers using standard channels of distribution – or long channels - are looking for convenience, healthy products and competitive prices. These consumers seem to be confused between organic and natural products. The offer diversification is definitely occurring through all types of channels but using different ways. For short channels, rethinking the distribution by moving towards cooperative based systems is a way to provide the consumers with a wider variety of products. For long channels, the complex system of distribution in place allows for a large variety of products from various country of origin. Moreover, differences between long and short channels is noticeable in terms of type of OF products as the former is offering an increasing variety of packaged goods, which certainly appeals to consumers looking for convenience. Processed OF products offered by short channels will very likely not evolve the same way. On the other hand, another significant trend is providing a significant interest for short channels: by selling organic based on a philosophical approach they also directly promote local products. This highlights the clear interest for the origin of the product for hardcore consumers using short distribution channels. Localized food system prevails to the extend that the local origin overrides in some cases the organic nature of the product. Local organic is the most valued product by short channels users but at the same time, the clear attractiveness for local products is not encouraging small size farmers to support the mandatory organic certification process. 9 The main challenges of the OF market varies depending on the type of distribution channel. More specifically, for short channels, while value building is based on community, relationship, the challenge lies in countering extended centralized distribution while keeping distribution costs low. Moreover, in order to not be co-opted by big players, small distributors work to maintain brand integrity. Long channels are increasingly relying on brand name and convenience to be competitive, whereas variety and convenience are part of their value building strategy. Considering the overall OF market growth, the distribution system in place relies on different types of channels that combined together serves occasional as well as hardcore consumers. Results of this study clearly highlight a very local value chain co-existing with a more complex global value chain applying distinctive strategies to maintain their competitiveness and cater to different types of OF consumers through specific value building. This ultimately leads to consider further implications in terms of store positioning and consumers store choice as OFs will still remain value-based products in comparison to conventional products. The existing differences in the production methods and the distribution systems, as well as consumers’ specific interests and knowledge about OF, will very likely continue to affect value creation in the current value chain while generating overall market growth. REFERENCES Canadian General Standards Board (2011). “Organic Production Systems General Principles and Management Standards”, CAN/CGSB-32.310-2006. Hall A. and Mogyorody V. (2001). “Organic farmers in Ontario: an examination of the conventionalization argument”, Sociologia Ruralis, 41 (4), 299-322. Hamzaoui Essoussi, L., Sirieix, L., Zahaf, M. (2013). “Trust Orientations in the Organic Food Distribution Channels: A Comparative Study of the Canadian and French Markets“, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20 (3), 292-301. Hamzaoui L. and Zahaf M. (2009). “Exploring the decision making process of Canadian organic food consumers: motivations and trust issues”, Qualitative Market Research, 12 (4), 443-459. Kassarjian H. (1977). “Content Analysis in Consumer Research”, Journal of Consumer Research, 4 (1), p. 8. Organic Monitor (2007). The Global Market for Organic Food and Drink, Organic Monitor, London. Prothero, A., Dobscha, S., Freund, J., Kilbourne, W.E., Luches, M.G., Ozanne, L.K., and Thogersen, J. (2011). “Sustainable consumption: opportunities for consumer research and public policy”, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 30 (1), 31-38. Smithers, J., Lamarche, J. and Alun, J. (2008). “Unpacking the terms of engagement with local food at the Farmers’ Market: Insights from Ontario”, Journal of Rural Studies, 24 (3), 337-350. Tutunjian, J. (2008). “Market survey 2007”, Canadian Grocer, 122 (1), 26-34. 10