* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Gains from Financial Globalization

Systemic risk wikipedia , lookup

Household debt wikipedia , lookup

International investment agreement wikipedia , lookup

Business valuation wikipedia , lookup

Present value wikipedia , lookup

Investment management wikipedia , lookup

Financial economics wikipedia , lookup

Negative gearing wikipedia , lookup

Global financial system wikipedia , lookup

Investment fund wikipedia , lookup

Global saving glut wikipedia , lookup

The Millionaire Next Door wikipedia , lookup

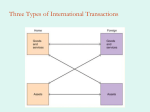

Gains from Financial Globalization First, we study factors that limit international borrowing and lending. Second, we see how a nation’s ability to use international financial markets allows it to accomplish three different goals: 1. Consumption smoothing (keeping consumption steady as income fluctuates) 2. Efficient investment (borrowing to invest in productive capital) 1. Diversification of risk (trading of financial assets between countries) Limits on Borrowing from Abroad: the long-run budget constraint • The ability to borrow in times of need and lend in times of prosperity has profound effects on a country’s well-being. • We first derive the long-run budget constraint (LRBC) - the constraint that limits a country’s foreign borrowing in the long run. • The LRBC shows precisely how and why a country must, in the long run, “live within its means.” use changes in an open economy’s external wealth to derive The long-run budget constraint • A household borrows $100,000 at 10% annually. The household can deal with its debt in different ways, for example: • Case 1 The debt is serviced. The borrower pays the interest but never needs to repay any principal. • Case 2 The debt is not serviced. The borrower pays neither interest nor principal. The debt grows by 10% every year. • Case 2 is not sustainable. This is often called a rollover scheme, a pyramid scheme, or a Ponzi game. This case illustrates the limits on the use of borrowing. • In the long run, lenders will simply not allow the debt to grow beyond a certain point. This requirement is the essence of the long-run budget constraint. The Long-Run Budget Constraint For a Country What we assume: 1. Prices are perfectly flexible. All analysis can be conducted in terms of real variables, so that monetary aspects of the economy can be ignored. 2. The country is a small open economy. The country cannot influence prices in world markets for goods and services. 3. All debt carries a real interest rate r*, the world real interest rate, which is constant. The country can lend or borrow an unlimited amount at this interest rate. The Long-Run Budget Constraint For a Country More assumptions we make: 4. The country pays a real interest rate r* on its start-of-period debt liabilities L and is paid the same interest rate r* on its start-ofperiod debt assets A. Net interest income payments equal to r*A minus r*L, or r*W, where W is external wealth (A − L) at the start of the period. 5. There are no unilateral transfers (NUT = 0), no capital transfers (KA = 0), and no capital gains on external wealth. Under these assumptions, there are only two nonzero items in the current account: the trade balance and net factor income from abroad, r*W. Calculating the Change in Wealth Each Period WN WN WN –1 TBN Change in external wealth this period Trade balance this period * r WN –1 Interest paid/received on last period's external wealth Calculating Future Wealth WN External wealth at the end of this period TBN Trade balance this period (1 r ) WN –1 * Last period's external wealth plus interest paid/received The Budget Constraint in a Two-Period Example At the end of year 0, W 0 (1 r* )W 1 TB0 Assume that all debts owed or owing must be paid off, and the country must end that year with zero external wealth. of year 1 At the end W1 0 (1 r * )W0 TB1 Substituting, we get W1 0 (1 r * ) 2W1 (1 r * )TB0 TB1 The two-period budget constraint is (1 r* ) 2 W 1 (1 r* )TB0 TB1 A two-period example Let W-1 = - $110 million, and r = 10% • To pay off $110 million at the end of period 1, the country must have a present value of future trade balances of +$110 million. • The country could run a trade surplus of $110 million in period 0, or it could wait to pay off the debt until the end of period 1, and run a trade surplus of $121 million in period 1. • Or it could use any other combination of trade balances in periods 0 and 1 that allow it to pay off the debt with the accumulated interested so that external wealth at the end of period 1 is zero. The long-run budget constraint in general We let N go to infinity to get the equation of the LRBC: (1 r )W1 * Minus the present value of wealth from last period TB3 TB1 TB2 TB4 TB0 * * 2 * 3 * 4 (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) Present value of all present and future trade balances • A debtor (surplus) country must have future trade balances that are offsetting and positive (negative) in present value terms. A Long-Run Example: The Perpetual Loan • The formula below helps us compute PV(X) for any stream of constant payments: X X X X PV ( X ) * * * 2 * 3 (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) r • For example, the present value of a stream of payments on a perpetual loan, with X = 100 and r*=0.05, equals 2,000: 100 100 100 2 3 (1 0.05) (1 0.05) (1 0.05) 100 2,000 0.05 Implications of the LRBC for GNE and GDP • The LRBC tells us that in the long run, a country’s national expenditure (GNE) is limited by how much it produces (GDP). To see this, we use the equation for the LRBC and the fact that TB GDP GNE GDP1 GDP2 GNE1 GNE2 (1 r )W1 GDP0 GNE0 * * 2 * * 2 (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) PV of wealth * from last period PV of current and future GDP PV of current and future GNE • The left side of this equation is the present value of resources of the country in the long run: the present value of any inherited wealth plus the present value of present and future product. • The right side is the present value of all present and future spending (C + I + G), measured by GNE. The Limits on Borrowing • The long-run budget constraint says that in the long run, in present value terms, a country’s expenditures (GNE) must equal its production (GDP) plus any initial wealth. • The LRBC therefore shows quite precisely how an economy must live within its means in the long run. The U.S LRBC and Exorbitant Privilege • Since the 1980s, the United States has been a net debtor, W = A − L < 0. Negative external wealth would lead to a deficit on net factor income from abroad: r*W= r* (A − L) < 0. But we learned that U.S. net factor income from abroad has been positive for decades. How can this be? • The only way a net debtor can earn positive net interest income is by receiving a higher rate of interest on its assets than it pays on its liabilities. • In the 1960s, Charles de Gaulle, complained about the United States’ “exorbitant privilege” of being able to borrow cheaply while earning higher returns on U.S. external assets. The U.S LRBC: more benefits • The U.S. has long received positive capital gains, KG, on its external wealth. • These large capital gains on external assets and the smaller capital losses on external liabilities are not the result of price or exchange rate effects. They are gains that cannot be otherwise measured. As a result, some skeptics call these capital gains “statistical manna from heaven.” • This financial gain for the U.S. is a loss for the rest of the world. As a result, some economists describe the United States as more like a “venture capitalist to the world” than a “banker to the world.” The U.S LRBC • Adding the 2% capital gain differential to the 1.5% interest differential, we end up with a U.S. total return differential (interest plus capital gains) of about 3.5% per year since the 1980s. In the same period, the total return differential was about zero in every other G7 country. • Adding these additional effects to the budget constraint for the U.S., we get WN WN WN –1 Change in external wealth this period TBN Trade balance this period r *WN –1 Interest paid/received on last period’s external wealth (r * r 0 ) L Income due to interest rate differenti al KG Capital gains on external wealth Conventional effects Additionaleffects External Wealth of the United States: Favorable Interest Rates and Capital Gains Emerging Markets • The United States borrows low and lends high. For most poorer countries, the opposite is true. Because of country risk, investors typically expect a risk premium before they will buy any assets issued by these countries, whether government debt, private equity, or FDI profits. Public debt and bond ratings Problems for Emerging Market Borrowers In a sudden stop, a borrower country sees its financial account surplus rapidly shrink. The math of the long-run budget constraint • Begin with the standard identity for the change in external wealth: WN WN WN –1 CAN KAN KG N • The change in a country’s external wealth equals the sum of the CA and KA plus capital gains on external wealth, KG . • Replacing the current account with its components leads to WN WN WN –1 TBN r WN –1 NUTN KAN KG N * • Next, we can rearrange this to write external wealth at the end of year N as WN 1 r WN –1 TBN NUTN KAN KG N * The math of the long-run budget constraint • To keep the algebra simple, for the time being, we will assume that NUTN KAN KG N 0 • We find a relationship between external wealth this year and future year’s trade balances, TB, by repeatedly adding equations like this to get WN 1 r * WN –1 TBN WN 1 TBN 1 WN * * 1 r 1 r WN 2 1 r * 2 WN 1 TBN 2 2 * * 1 r 1 r The math of the long-run budget constraint Adding these three identities leads to WN 1 WN 2 WN 1 TBN 1 TBN 2 * WN 1 r WN –1 WN TBN 2 2 * * * * * 1 r 1 r 1 r 1 r 1 r Cancelling terms that appear on both sides of the equation gives us WN 2 1 r * 2 TBN 1 TBN 2 1 r WN –1 TBN * * 2 1 r 1 r * The math of the long-run budget constraint Extrapolating leads to our equation, TBN 1 TBN 2 TBN 3 0 1 r WN –1 TBN ... 2 3 * * * 1 r 1 r 1 r If WN T 1 r * T * 0 This means that WN T does not grow as 1 r some country’s debt is growing explosively. * T or faster. If it did, The math of the long-run budget constraint • The LRBC is TBN 1 TBN 2 TBN 3 1 r WN –1 TBN ... 2 3 * * * 1 r 1 r 1 r * • If NUT KA KG is not zero, TB is replaced by TB NUT KA KG • For the U.S., we will also need to include r * r0 LN 1 1. The Gains from Consumption Smoothing Some additional assumptions: • GDP is denoted Q. Output is produced using only labor. Production of GDP may be subject to shocks. • Think of a country as a collection of households. Households prefer consumption C that is constant over time, or smooth. • The country must satisfy the long-run budget constraint. Gains from Consumption Smoothing • For now, assume investment I and government spending G are zero. In this case, GNE equals C. • At time 0, the country has zero initial wealth, W−1 =0. • Assume the country is small and the rest of the world (ROW) is large, and the prevailing world real interest rate is constant equal to r. Gains from Consumption Smoothing These assumptions give us a special case of the LRBC that requires the present value of current and future trade balances to equal zero (because initial wealth is zero): W-1 = 0 = Present value of TB = Present value of Q - Present value of C That is, Present value of GDP = Present value of GNE Closed Versus Open Economy: No Shocks A Closed or Open Economy with No Shocks Output equals consumption. Trade balance is zero. Consumption is smooth. Closed versus Open Economy: Shocks A Closed Economy with Temporary Shocks Output equals consumption. Trade balance is zero. Consumption is volatile. Closed versus Open Economy: Shocks An Open Economy with Temporary Shocks A trade deficit is run when output is temporarily low. Consumption is smooth. When output fluctuates, a closed economy cannot smooth consumption, but an open one can. Gains from Consumption Smoothing • Suppose output Q and consumption C are initially constant, equal (Q = C), and external wealth is zero. The LRBC is satisfied. • If output falls in year 0 by ΔQ, for just one year and then returns to its level for all future periods, then the present value of output decreases by ΔQ. • To meet the LRBC, a closed economy reduces its consumption by the whole ΔQ in year 0. • An open economy can smooth its consumption by reducing C every year by a smaller amount, so that ΔC < ΔQ. Gains from Consumption Smoothing • A loan of ΔQ − ΔC in year 0 requires interest payments of r*(ΔQ − ΔC) in future years. Beginning in year 1, trade surpluses of ΔC equal these interest payments. The change in ΔC is chosen so that C is constant. r ´ (DQ - DC) = DC * • Rearranging, r* C Q * 1 r Smoothing Consumption when a Shock Is Permanent • With a permanent shock, output falls by ΔQ forever, so the only way either a closed or open economy can satisfy the LRBC and smooth consumption is to cut consumption by ΔC= ΔQ every year. • Comparing the results for a temporary shock and a permanent shock: consumers can smooth out temporary shocks, but they must adjust completely to permanent shocks. Summary • Financial openness allows countries to “save for a rainy day.” Without financial institutions to lend or borrow, you have to spend what you earn each period. • Using financial transactions to smooth consumption fluctuations makes a household and/or country better off. • In an open economy, consumption can be smoothed by running a trade deficit in bad times and a trade surplus in good times. • Deficits and surpluses can be used to finance emergency spending. Consumption smoothing and war Japan’s gross saving and investment during the RussoJapanese War, 1904-1905 Year Saving/GDP Investment/GDP 1903 0.131 0.136 1904 0.074 0.120 1905 0.058 0.168 1906 0.153 0.164 Wars and U.K. Current Account and Government Deficits Consumption Volatility and Financial Openness • Does the evidence show that countries avoid consumption volatility by embracing financial globalization? • The ratio of a country’s consumption volatility to its output volatility should fall if openness fosters consumption smoothing. • Since not all shocks are global, countries ought to be able to achieve some reduction in consumption volatility through external finance. Consumption Volatility and Financial Openness • The lack of evidence suggests that some of the relatively high consumption volatility must be unrelated to financial openness. • Consumption-smoothing gains in emerging markets require improving poor governance and weak institutions, developing their financial systems, and limited financial integration. Precautionary Saving, Reserves, and Sovereign Wealth Funds • Countries may engage in precautionary saving: the government accumulates a buffer of external assets. • Two forms of precautionary saving by governments: (1) Foreign reserves held by central banks; (2) Sovereign wealth funds - state-owned asset management companies invest some of the government savings. 2. Gains from Efficient Investment • On the investment side, financial openness can improve a country’s ability to increase capital and take advantage of new production opportunities. • Assume that production requires both labor and capital. Capital is created over time through investment. The LRBC must be modified to include investment I as a component of GNE. We still assume that G is zero. • When initial wealth is 0 , the LRBC is: 0 = Present value of TB Gains from Efficient Investment • Because Present value of TB = 0, Present value of Q = Present value of C + Present value of I • A closed economy, external borrowing and lending are not possible, and the trade balance is zero in all periods. • An open economy, borrowing and lending are possible, the trade balance can be more or less than zero, and the LRBC must be satisfied. Efficient Investment: A numerical example Q = 100, C = 100, I = 0, TB = 0, and W = 0. A shock in year 0 arrives as a new investment opportunity requiring an expenditure of 16 units. This will pay off in future years, increasing the country’s output by 5 units in year 1 and all subsequent years (but not in year 0). With investment, output is 100 today and 105 in every subsequent year. The present value of this output is 100 + 105/0.05 = 2,200. The present value of consumption must equal Q – I = 2,200 – 16 = 2,184. Efficient Investment: A numerical example Efficient Investment • A new investment opportunity requires ΔK units of output in year 0. This investment will lead to ΔQ more units of output every year starting in year 1. • The rise in PV(Q) comes from extra output in every year but year 0: Change in present value of output Q Q Q * * 2 * 3 (1 r ) (1 r ) (1 r ) Q * r • The change in PV(I) is ΔK. Investment will increase the present value of consumption if and only if ΔQ/r* ≥ ΔK. Efficient Investment • Rearranging, the investment should be made if Q r K * • Dividing by ΔK, Q r* K • Firms invest if the MPK, is at least as great as the real interest rate. Gains from Efficient Investment • In an open economy, firms borrow and repay to make investments that maximizes the PV of output. • An open economy should investment until its MPK equals the world real rate of interest. • Financial openness allows countries to increase investment and smooth consumption at the same time. • In a closed economy, the consumption cost of investment cannot be smoothed. Example: North Sea oil boom and Norwegian investment Gains from Efficient Investment • These imply that capital should flow to higher MPK countries from lower MPK countries. • Since poor countries have low ratios of capital to labor, the MPK of capital should be higher in poorer countries than in rich (all else equal). Using the Production Function: output per worker, q = Q/L, is a function of capital per worker, k = K/L, and productivity A. Gains from Efficient Investment • A standard and widely used production function is written q A k Productivity Capital Output per worker level per worker • where 𝜃 is a number between 0 and 1 that measures the contribution of capital to production. 𝜃 is the elasticity of capital with respect to output and is about 1/3. The productivity level A is set at a reference level of 1. Then: q k 1/ 3 • MPK is the slope of the production function, is given by q q 1 Ak MPK k k • Mexico’s output per worker is about 43% of that for the U.S. • If the level of productivity, A, is the same, then k for Mexico is 43% of k for the U.S. • Investment in Mexico should increase k and output per worker until they are the same as in the U.S. Why Doesn’t Capital Flow to Poor Countries? • This doesn’t happen in reality. Poor and rich countries have different levels of productivity. MPK may not be much higher in poor countries than it is in rich countries. • Instead, output is proportional to A given capital per worker: q A k If MPK is the same between the two countries, output per worker and capital per worker are lower in the country with a lower A. q MPK k • The poorer country (Mexico) is now at C and not at B. Investment increases k only until MPK is the same as in the U.S. at point D. • Capital per worker k and output per worker q do not converge to the levels seen in the rich country. Why Doesn’t Capital Flow to Poor Countries? This is called the Lucas paradox from Nobel laureate Robert Lucas’ article “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?” Lucas noted that if international financial markets are open to free movements of resources, then investment goods should flow from rich to poor countries and investment should be very low in wealthy countries. What if Countries Have Different Productivity Levels? • Suppose that AUS AMEX and output is produced in each country using the technologies qUS AUS kUS qMEX AMEX k MEX The MPKs are related as MPK MEX [qMEX / k MEX ] qMEX / qUS MPKUS [qUS / kUS ] k MEX / kUS What if Countries Have Different Productivity Levels? If then MPK MEX MPKUS r * qMEX AMEX qUS AUS k MEX kUS Capital per worker in Mexico is about 1/3 of the ratio of capital per worker in the U.S.. If Mexico has the same productivity as the U.S., then Mexico’s output per worker should be about is about 69% of U.S. 1 output per worker. That is, Instead, it is 43% as much. k MEX qMEX qUS kUS 1 3 0.69 3 What if Countries Have Different Productivity Levels? If the MPK is equal between Mexico and the U.S., we can estimate the difference between productivity levels in Mexico and the U.S. using this equation, qMEX AMEX qUS AUS k MEX kUS AMEX AUS 1 3 1 . 3 If the MPK’s are equal, then Mexico’s productivity level should be 63% of the U.S. productivity level. Comparing A and k as sources of output differences Comparing A and k as sources of output differences Comparing A and k as sources of output differences • Differences in A could reflect a country’s technical efficiency, construed narrowly as a function of its technology and management capabilities. • Many economists believe that the level of A may primarily reflect a country’s social efficiency, construed broadly to include institutions, public policies, and cultural differences. • Indeed, some evidence that, among poorer countries, more capital does tend to flow to the countries with better institutions. Comparing A and k as sources of output differences Other factors may also explain the lack of convergence. • Differences in MPK could be due to the cost of risk investing in an emerging market (e.g., risks of regulatory changes, tax changes, expropriation, and other political risks). • Risk premiums can be substantial in practice: for example, before the global financial crisis, the risk premium for Argentina was 25%, but for Mexico, it was 3%. Risk Premiums in Emerging Markets The risk premium measures the difference between the interest rate on the country’s long-term government debt and the interest rate on long-term U.S. government debt. The larger the risk premium, the more compensation investors require, given their concerns about the uncertainty of repayment. Gains for Diversification of Risk • Diversification can help smooth shocks by promoting risk sharing. With diversification, countries may be able to reduce the volatility of their incomes (and hence their consumption levels) without any net lending or borrowing. • An example: Two countries, A and B, with outputs that fluctuate asymmetrically. Two possible “states of the world,” with equal probability of occurring. State 1 is a bad state for A and a good state for B; state 2 is good for A and bad for B. We assume that all output is consumed (there is no investment or government spending). Output is divided 60-40 between labor income and capital income. Gains for Diversification of Risk - example • No diversification means that each country owns 100% of its capital. Output is the same as income. Suppose that in state 1, A’s output is 90, of which 54 units are payments to labor and 36 units are payments to capital In state 2, A’s output rises to 110, and factor payments rise to 66 for labor and 44 units for capital. The opposite is true in B: in state 1, B’s output is higher than it is in state 2. The variation of GNI about its mean of 100 is plus or minus 10 in each country. Because households prefer smooth consumption, this variation is undesirable. Example without diversification Gains for Diversification of Risk - example • Diversification allows the two countries to partially smooth national income by holding portfolios of capital assets in each country. For example, each country could own half of the domestic capital stock, and half of the other country’s capital stock. Indeed, this is what standard portfolio theory says that investors should try to do. For our example, capital income is smoothed at 40 units for each country (same in each state 1 or 2). Total capital income is 80 in each state, so each country receives a constant share of 40. Because labor income is not shared, each country’s GNI still fluctuates around a mean of 60 by plus or minus 6. Example with diversification Gains for Diversification of Risk - example • What happens if each country owns 100 percent of other country’s capital stock? • In state 1 (bad for Country A), A’s labor income is 54. Capital income in country B belongs to country A and equals 44. GNI for Country A is now 54 + 44 = 98. • In state 2 (good for Country A), A’s labor income is 66 and its income from capital (in Country B) is 36. GNI for Country A equals 102. • GNI fluctuates around a mean of 100 plus or minus only 2 in each country. Example with more diversification Gains for Diversification of Risk and the Balance of Payments • Consider country A. In state 1 (bad for A, good for B), A’s income or GNI exceeds A’s output. The extra income is net factor income from abroad, which is the difference between the income earned on A’s external assets and the income paid on A’s external liabilities. With that net factor income, country A runs a negative trade balance, which means that A can consume more than it produces. • Adding the trade balance of –4 to net factor income from abroad of +4 means that the current account is 0, and there is still no need for any net borrowing or lending. • These flows are reversed in state 2 (good for A, bad for B). Capital income smoothing • Each country’s payments to capital are volatile. A portfolio of 100% country A’s capital or 100% of country B’s capital has capital income that varies by plus or minus 4 (between 36 and 44). But a 50-50 mix of the two leaves the investor with a portfolio of minimum, zero volatility (it always pays 40). • In general, there will be some common shocks, which are identical shocks experienced by both countries. In this case, there is no way to avoid this shock by portfolio diversification. • But as long as some shocks are asymmetric, the two countries can take advantage of gains from the diversification of risk. Return Correlations and Gains from Diversification The charts plot the volatility of capital income against the share of the portfolio devoted to foreign capital. The two countries are identical in size and experience shocks of similar amplitude. In panel (a), shocks are perfectly asymmetric (correlation = −1), capital income in the two countries is perfectly negatively correlated. Risk can be eliminated by holding the world portfolio, and there are large gains from diversification. Return Correlations and Gains from Diversification (continued) In panel (b), shocks are perfectly symmetric (correlation = +1), capital income in the two countries is perfectly positively correlated. Risk cannot be reduced, and there are no gains from diversification. In panel (c), when both types of shock are present, the correlation is neither perfectly negative nor positive. Risk can be partially eliminated by holding the world portfolio, and there are still some gains from diversification. Limits to Diversification: Capital versus Labor Income • Labor income risk (and hence GDP risk) may not be diversifiable through the trading of claims to labor assets or GDP. • But capital and labor income in each country are perfectly correlated, and shocks to production tend to raise and lower incomes of capital and labor simultaneously. This means that, as a risk-sharing device, trading claims to capital income can substitute for trading claims to labor income. The Home Bias Puzzle • In practice, we do not observe countries owning foreign-biased portfolios or even the world portfolio. • Countries tend to own portfolios that suffer from a strong home bias, a tendency of investors to devote a disproportionate fraction of their wealth to assets from their own home country, when a more globally diversified portfolio might protect them better from risk. The Home Bias Puzzle Portfolio Diversification in the United States The figure shows the return (mean of monthly return) and risk (standard deviation of monthly return) for a hypothetical portfolio made up from a mix of a pure home U.S. portfolio (the S&P 500) and a pure foreign portfolio (the Morgan Stanley EAFE) using data from the period 1970 to 1996. The Home Bias Puzzle The Globalization of Cross-Border Finance Gains from Diversification of Risk: Summary • If countries could borrow and lend without limit or restrictions in an efficient global capital market, they should be able to cope quite well with the array of possible shocks, in order to smooth consumption. • In reality, as the evidence shows, countries are not able to fully borrow and choose not to lend so freely. • In theory, if countries were able to pool their income streams and take shares from that common pool of income, all country-specific shocks would be averaged out. Countries would be exposed only to common global shocks to income. Global shocks are systemic (shocks to the entire system) and are never diversifiable. Gains from Diversification of Risk: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” • Financial openness allows countries, like households, to follow this adage. • In practice, risk sharing through asset trade is limited. First, the number of assets is limited. The market for claims to capital income is incomplete because not all capital assets are traded (e.g., many firms are privately held and are not listed on stock markets), and trade in labor assets is legally prohibited. • Even so, investors have tended to include foreign assets in their wealth portfolios much less than they could. This appears to be changing slowly in the presence of ongoing financial globalization. The gains from financial globalization: summary Financial markets allow: • households to save and borrow to smooth consumption over shocks to their income. • firms to borrow in order to invest efficiently and permit investors to diversify their holdings across a wide range of assets. • International financial markets should allow the same gains subject to the long-run budget constraint. Countries face national income shocks, new investment opportunities and country-specific risks. The gains from financial globalization: Summary These Gains are Elusive: • In poorer countries, we do not see consumption smoothing gains, and there is little scope for development based on external finance until productivity levels are improved. • Financial globalization hasn’t really been fully tried yet. Many emerging markets still have large barriers to full financial liberalization. • Institutional weaknesses in these countries most likely inhibit gains from financial integration and might turn financial liberalization to a detriment rather than benefit. It is possible that financial openness stimulates competition, transparency, and accountability. • The benefits of financial globalization are likely to be much smaller for these countries, and they must also be weighed against potential offsetting costs, such as the risk of crises.