* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Simple Model of Labor Demand

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

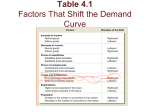

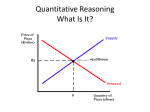

1 Lecture 4: The Demand for Labor The demand for labor is a derived demand. Employer’s demand for labor is a function of the characteristics of demand in the product market. It is also a function of the characteristics of the production process. Two important features of the demand for labor: 1. It can be shown theoretically and empirically that labor demand curves slope downward. 2. The quantity of labor demanded has varying degrees of responsiveness to changes in the wage. When the demand for labor is analyzed, two sets of distinctions are made: 1. Demand by firm v.s. the demand curves for an entire market. Note: Firm and market labor demand curves have different properties although both slope downward. 2. The time period for which the demand curve is drawn. Short Run: A period over which a firm’s capital stock is fixed. Long Run: A period over which a firm is free to vary all factors of production. A Simple Model of Labor Demand Assumptions: (1) Employers seek to maximize profit. (2) Firms employ two homogeneous factors of production, employee-hours (E) and capital (K), in their production of goods and services. Their production function can be written as: Q = f(E, K) (3) Hourly wage cost is the only cost of labor. Note: We ignore hiring, training cost and fringe-benefit costs for the time being. (4) Both a firm’s labor market and its product market are competitive. 1. Short-Run Demand for Labor by Firms Defn. Marginal Product of Labor: The change in output resulting from hiring an additional worker, holding constant the quantities of all other input. 2 Defn. Law of Diminishing Returns: Eventually each additional increment of labor produces progressively smaller increments of output. Defn. Value of the Marginal Product (VMP): The dollar values of the additional output produced by an additional worker. VMP = P * MPE The profits are maximized by the competitive firm when the value of marginal product of labor is just equal to its marginal cost. Profit-Maximizing condition: Labor should be hired until its marginal product equals the real wage. i.e., MPE = W/P The firm’s demand for labor in the short run is equivalent to the downward-sloping segment of its marginal product of labor schedule. Note: The downward-sloping nature of the short-run labor demand curve 3 is based on an assumption that MPE declines as employment is increased. Elasticity of Labor Demand We measure the responsiveness of labor demand to changes in the wage rate by using an elasticity. The short-run elasticity of labor demand, SR, is defined as the percentage change in short-run employment resulting from a 1 percent change in the wage: SR = (%△ESR)/ (%△w) Since the labor demand curves slope downward, an increase in the wage rate will cause employment to decrease; the (own-wage) elasticity of demand is a negative number. Note: |SR| >1: a 1% increase in wage will lead to an employment decline of greater than 1% → elastic demand curve |SR| < 1: a 1% increase in wage will lead to a proportionately smaller decline in employment → inelastic demand curve Elastic demand: aggregate earnings↓ when w↑ Inelastic demand: aggregate earnings↑ when w↑ 4 2. Market Demand Curve A market demand curve is just the summation of the labor demanded by all firms in a particular labor market at each level of the real wage. Note: When aggregating labor demand to the market level, product price can no longer be taken as given, and the aggregation is no longer a simple summation. However, the market demand curves drawn against money wages, like those drawn as functions of real wages, slope downward. 3. Long-Run Demand for Labor by Firms In the long run, employers are free to vary their capital stock as well as the number of workers they employ. Profit Maximization’s Dual Problem – Cost Minization Defn. Isoquant: An isoquant describes the possible combination of labor and capital which produce the same level of output. Defn. The Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution: The slope of an isoquant is the negative of the ratio of marginal products. The absolute value of the slope of an isoquant is called the marginal rate of technical substitution. Defn. Isocost: The isocost line gives the menu of different combinations of labor and capital which are equally costly. A profit-maximizing firm that is producing q0 units of ouptut wants to produce these units at the lowest possible cost. →The firm chooses the combination of labor and capital where the isocost is tangent to the isoquant. i.e., MPE/MPK = w/r → Cost-minimization requires that the marginal rate of technical substitution equal the ratio of prices. 5 Note: To be minimizing cost, the cost of producing an extra unit of output by adding only labor must equal the cost of producing that extra unit by employment only additional capital. i.e., MPE / w = MPK /r The Effect of Change in w Increase in w: (1) Substitution Effect As w increase, labor cost rises, and more capital and less labor are used in the production process. (2) Scale effect The new-profit-maximizing level of production will be less. How much less cannot be determined unless we know something about the product demand curve. Both the substitution effect and the scale effect work in the same direction. So these effects lead us to assert that the long-run demand curve for labor slopes downward. Note: In general, if a firm is seeking to minimize costs, in the long run it should employ all inputs up until the point that the marginal cost of producing a unit of output is the same regardless of which input is used. 6 Defn. The Elasticity of Substitution: The elasticity of substitution gives the percentage change in the capital/labor ratio resulting from a 1 percent change in the relative price of labor. The size of the substitution effect directly depends on the magnitude of the elasticity of substitution. 4. Marshall’s Rules of Derived Demand (The Hicks-Marshall Law of Derived Demand) The factors that influence own-wage elasticity can be summarized by the four “Hicks-Marshall Laws of Derived Demand.” These laws assert that, other things equal, the own-wage elasticity of demand for a category of labor is high under the following conditions: (1) When the price elasticity of demand for the product being produced high; (2) When other factors of production can be easily substituted for the category of labor; (3) When the supply of other factors of production is highly elastic; (4) When the cost of employing the category of labor is a large share of the total cost of production. Note: (1), (2) and (3) can be shown to always hold. There are conditions, however, under which the final law does not hold. (1) Demand for the Final Product The greater the price elasticity of demand for the final product, the larger will be the decline in output associated with a given increase in price and the greater the decrease in output, the greater the loss in employment (other things equal). Thus the greater the elasticity of 7 demand for the product, the greater the elasticity of demand for labor will be. (2) Substitutability of Other Factors Other things equal, the easier it is to substitute other factors in production, the higher the wage elasticity of demand will be. Note: a. Sometimes collectively bargained or legislated restrictions make the demand for labor less elastic by reducing substitutability (not technically). b. Substitution possibility that are not feasible in the short run may well become feasible over longer periods of time, when employers are free to vary their capital stock. → The demand for labor is more elastic in the longer run than in the short run. (3) The supply of Other Factors As the wage rate increased and employers attempted to substitute other factors of production for labor, the prices of these inputs were bid up substantially. Such a price increase would dampen firm’s appetites for capital and thus limit the substitution of capital for labor. Note: Prices of other inputs are less likely to be bid up in the long run than in the short run. → Demand for labor will be more elastic in the long run. (4) The Share of Labor in Total Costs The greater the category’s share in total costs, the higher the wage elasticity of demand will tend to be. If the share of labor cost is large, cost increase due to wage increase is larger. The employer would have to increase their product prices by more, output and hence employment would fall more. Note: This law, relating a smaller labor share with a less-elastic demand curve, holds only when it is easier for customers to substitute among final products than it is for employers to substitute capital for labor. 5. The Cross-Wage Elasticity of Demand The elasticity of demand for input j with respect to the price of input k is the percentage change in the demand for input j induced by 1 percent change in the price of input k. i.e., 8 jk = %△E j%△Wk jk = %△Ek%△Wj If the cross elasticities are positive (with an increase in the price of one increasing the demand for the other) the two are said to be gross substitutes. If the cross elasticities are negative (and increase in the price of one reduces the demand for the other), the two are said to be gross complements. Note: Whether two inputs are gross substitutes or gross complements depends on both the production function and the demand conditions. → Knowing that two groups are substitutes in production is not sufficient to tell us whether they are gross substitutes or gross complements.