* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Polymorphous ventricular tachycardia: clinical

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

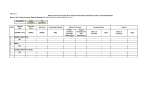

THERAPY AND PREVENTION VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA Polymorphous ventricular tachycardia: clinical characterization, therapy, and the QT interval PHuC TITo NGUYEN, B.S., MELVIN M. SCHEINMAN, M.D., AND JOHN SEGER, M.D. Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 ABSTRACT Forty-five consecutive patients with polymorphous ventricular tachycardia (PVT) were studied. The arrhythmia proved to be of a drug-related cause in 27 and due to an electrolyte disorder in four patients. Coexistent cardiac diseases without metabolic or drug-related abnormalities included ischemic heart disease in three, cardiomyopathy in three, and mitral valve prolapse in two. PVT was exercise-induced in four and associated with bradyarrhythmias in two. A prolonged QT or corrected QT interval was inconsistently related to the occurrence of PVT. In patients in whom PVT was induced by certain type I drugs, other type I antiarrhythmic drugs were usually either ineffective or resulted in aggravation of arrhythmia. For the group as a whole, treatment with lidocaine resulted in inconsistent beneficial effects, while cardiac pacing was almost universally effective for those with drug-induced PVT, regardless of the length of the QT interval. Long-term amiodarone therapy proved safe and effective for 12 of the 24 patients with drug-induced PVT who required long-term therapy for their original arrhythmia. We conclude that identification of PVT is the key clinical issue and that the QT interval is not necessarily the prime abnormality nor the variable to be considered in predicting success of therapy. Temporary cardiac pacing appears to be very effective in the short-term management of these patients. Use of type I antiarrhythmic agents in patients with drug-induced PVT generally resulted in aggravation of arrhythmia. In contrast, long-term amiodarone therapy for control of the original arrhythmia appears to be a promising approach for those with PVT associated with type I agents. Circulation 74, No. 2, 340-349, 1986. THE CLINICAL characterization of polymorphous ventricular tachycardia (PVT) has been incomplete. The definition of PVT we have used is similar to that proposed by the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology, namely ventricular tachycardia with an unstable (continuously varying) QRS complex morphology in any recorded electrocardiographic lead.' In addition, we require a ventricular rate greater than 200/min for at least 10 complexes. This definition includes but is not limited to the classic torsade de pointes pattern.2 Diagnostic criteria for torsade de pointes includes the presence of a prolonged QT interval, and others have emphasized the clinical importance of this arrhythmia. ` Since the clinical implication of PVT is not clear, the purpose of the present study is threefold: (1) to define the clinical characteristics of PVT, (2) to assess the efficacy of available emergent and long-term therapy for this arrhythmia, and (3) to examine the imporFrom the Department of Medicine and the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco. Address for correspondence: Melvin M. Scheinman, M.D., Room 312 Moffitt Hospital, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143-0214. Received Oct. 29, 1985; revision accepted April 24, 1986. 340 tance of the QT interval in patients with this arrhyth- mia. Materials and methods Data for this study were collected retrospectively for 1 year and prospectively over 1.8 years for all patients admitted to the University of California Medical Center, San Francisco, with the diagnosis of PVT. PVT was defined as a rapid (> 200/min) irregular ventricular tachycardia with continuous variation in QRS complexes of greater than 10 beat duration. This definition included but was not limited to the classic torsade de pointes pattern. All rhythm strips were reviewed to ascertain that the tachycardia fulfilled the above requirements. All patients had symptomatic arrhythmias and were continuously monitored in a coronary care unit. PVT was defined as drug induced if it developed as a new rhythm disturbance after initiation of drug therapy and it disappeared after cessation of administration of that drug. A total of 45 patients met these criteria and were included in the study. We excluded all patients who developed PVT as part of a preterminal cardiac state (i.e., those with severe end-stage heart failure or cardiogenic shock). In addition, patients with familial or idiopathic long QT syndrome were excluded, since these patients are described in detail in a separate report.8 Patients were included only if 12-lead sinus rhythm electrocardiograms had been recorded in them either just before or during interludes between bouts of PVT. Posttreatment QT intervals were not measured in seven patients who received permanent pacemakers. The following data were extracted from the medical records: age, sex, cardiac diagnosis, concurrent drug therapy, and drug CIRCULATION THERAPY AND PREVENTION-VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA to be absent at follow-up after hospital discharge. A treatment and electrolyte levels. The QT interval and the corrected QT (QTc) were determined from a 12-lead sinus rhythm electrocardiogram that was obtained on hospital admission, during interludes between episodes of active arrhythmia, and just before discharge. Retrospective data were obtained by examination of all medical records, including daily electrocardiographic rhythm strips. There was no significant difference in the incidence of PVT in retrospective vs prospectively entered patients. The QT interval was measured according to the method suggested by Lepeshkin9 and the QT was corrected for heart rate: QTc = QT/VRR. Short- and long-term therapy was noted and follow-up information was obtained either during visits to our arrhythmia clinic or from private physicians. - regiinen was deemed unsuccessful if PVT frequency remained the same or increased or if PVT recurred more than four drug half-lives after discontinuing an offending drug. The total number of episodes of PVT during short-term therapy was recorded (see table 2). Results The clinical data on the 45 patients are recorded in tables 1 to 3. There were 22 female and 23 male patients ranging in age from 15 to 82 years. The majority had organic cardiac disease, most frequently coronary A treatment regimen for PVT was judged successful if there artery disease and/or hypertension. Coexistent cardiac diseases without metabolic or drug-related abnormal- was complete cessation of the arrhythmia and was considered possibly successful if the arrhythmia decreased in frequency consistent with the drug half-life. In addition, for treatment to be considered successful PVT or symptomatic arrhythmias had ity included ischemic heart disease in three, cardio- TABLE 1 Drug-induced PVT Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Before Active Patient Age (yr)/ Sex No. level Drug (,ugg/ml) discharge arrhythmia Time K+ level elapsedA (meq/1)B QT QTc QT QTc years days days weeks days day days weeks years days years days days weeks weeks days months days 2 days 3 days 3.7 4.5 3.7 3.9 4.0 3.2 4.0 4.6 4.3 4.2 3.7 0.58 Pacedc 0.56 0.46 0.48 0.56 0.44 0.44 0.40 0.56 0.50 0.44 0.48 0.56 0.68 0.40 0.50 Paced 0.36 0.48 0.46 0.52 0.38 0.48 0.44 0.40 0.48 0.56 0.44 0.38 0.50 0.40 0.46 0.52 0.40 0.40 0.48 0.40 0.40 0.44 0.42 Original arrhythmia Type I drug 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 53/F 74/F 50/F 60/F 68/M 59/M 65/F 77/M 66/M 82/F 70/F 60/F 73/M 81/F 70/M 65/M 15/M 67/M 63/F 70/F 70/M 69/M 79/M Disopyramide Procainamide Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Procainamide Procainamide Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Procainamide Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Quinidine Procainamide Quinidine Procainamide Procainamide Quinidine Quinidine Sotalol 60/F 24D Amiodarone induced Amiodarone 73/M 25 1.3 3.4 3.8 6.4 11.1 4.9 2.1 1.9 2.9 4.2 5.4 1.2 11.3 4.2 3.8 3.4 - SVT PVC PVC A fib SVT SVT PVC SVT PVC PVC SVT A fib SVT A fib SVT A fib A fib SVT PVC PVC A fib USVT A fib USVT 1.5 3 8 1.5 2 1 4 2.2 1.5 8 2 2 7 2.5 3 9 3 3 2.5 0.48 5 2 days days days days 3.2 3.6 4.0 4.0 4.3 0.48 0.62 0.40 0.34 0.52 0.53 0.56 0.50 0.44 0.50 0.58 0.54 0.48 0.52 0.53 0.66 0.42 0.44 0.44 0.42 0.50 0.58 0.48 0.53 0.42 0.40 0.50 SVT 3 months 2.4 0.66 0.70 0.42 USVT USVT 1 day days 3.8 0.48 0.52 2 4.1 0.52 0.60 Paced PacedC 4 3 4.0 5.1 4.6 4.2 4.4 0.40 0.40 0.42 0.48 0.40 0.45 0.50 0.48 0.50 0.50 0.48 0.46 0.54 0.47 0.50 0.44 0.50 0.42 0.52 0.52 0.46 0.48 0.45 0.44 0.52 0.47 hypokalemia 26 27 61/F 68/M Amiodarone Amiodarone A fib = atrial fibrillation; PVC = premature ventricular complex; SVT = sustained ventricular tachycardia; USVT tachycardia. ATime from initiation of drug to onset of PVT. BAt the time of arrhythmia. CPerlmanent pacing. DSotalol in addition has both /3-blocker and class 1II antiarrhythmic action. Vol. 74, No. 2, August 1986 unsustamied vcntnicular 341 NGUYEN et al. myopathy in three, and mitral valve prolapse in two. PVT was induced by exercise in four and associated with bradyarrhythmia in two patients. Drug-induced PVT. Drug-induced PVT was associat- ed with quinidine in 15 patients, procainamide in seven, disopyramide and sotalol in one each, and amio- darone in three (table 1). These drugs were originally used to treat symptomatic unimorphic ventricular tachycardia in 13 patients, frequent premature ventricular depolarizations in seven, and atrial fibrillation in seven. In three of the 27 patients (Nos. 7, 19, and 20), associated mild hypokalemia was found at the time of TABLE 2 Treatment and follow-up of patients with drug-induced PVT Patient No. Baseline incidence of druginduced PVT l Initial treatmentA Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 1 2 2 2 Lidocaine Disopyramide 3 4 2 5 6 Lidocaine Lidocaine Procainamide 6 7 4 2 8 11 9 4 10 1 11 12 13 2 2 8 14 2 15 5 16 17 18 2 6 1 2 19 20 1 21 22 23 24 25 1 1 2 3 2 26 4 3 27 d/c 1 = Lidocaine Lidocaine, bretylium Phenytoin, lidocaine Short-term therapy PVT 2 2 Paced d/c disopyramide; lidocaine 3 2 4 34 8 Lidocaine, procainamide Lidocaine 1 2 2 0 6 7 2 2 2 28 25 d/c procainamide; lidocaine 0 None None Amiodarone 30 41 16 amiodarone 0 Outcome d/c bretylium; paced 0 Amiodarone Amiodarone 26 24 Paced 0 Procainamide 41 0 None 37 0 None 36 0 Amiodarone Disopyramide Amiodarone 39 26 0 No drugs 6 Sudden death Amiodarone 7 Death due to pulmonary toxicity iv d/c procainamide; lidocaine d/c procainamide; paced Paced Disopyramide d/c procainamide; paced 0 0 d/c procainamide; paced Tocainide Paced Paced Died suddenly 0 Digoxin, verapamil Propranolol Amiodarone 13 10 7 0 No drugs No drugs 12 6 Amiodarone Amiodarone Amiodarone Amiodarone Phenytoin 2 3 4 3 25 Phenytoin Phenytoin 26 18 0 0 Procainamide d/c because of side effects after 6 months 1 0 2 d/c bretylium and phenytoin; paced 0 12 4 Lidocaine 0 0 2 5 1 2 7 d/c bretylium; paced, start phenytoin 0 phenytoin, paced Phenytoin, paced Died of congestive heart failure 0 1 0 discontinued. Alnitial therapy included discontinuation of the offending drug listed in table 342 Follow-up (months) Nadolol None 0 0 therapy 0 0 0 2 Lidocaine Lidocaine Lidocaine, start sotalol Lidocaine Start bretylium, phenytoin Paced Procainamide Start procainamide Lidocaine Lidocaine, bretylium, paced Lidocaine, procainamide Quinidine PVT 1 0 Procainamide Lidocaine, procainamide Lidocaine, procainamide Lidocaine Subsequent therapy Long-term antiarrhythmic 1. CIRCULATION THERAPY AND PREVENTION-VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 PVT. All patients with drug-induced PVT had associated organic heart disease. All but one of the recorded instances of drug-induced PVT showed a long-short initiating sequence (figures 1 and 2). The time between initiation of therapy and the first documented episode of PVT was from 12 hr to 4 days in 12 and from 5 days to 2 weeks in seven. Eight patients developed PVT 2 weeks or more after initiation of drug therapy and possible aggravating factors resulting in induction of PVT included development of hypokalemia in two and bradycardia in one. One of the eight patients had double-outlet right ventricle and PVT developed after tricuspid valve replacement. The latter patient had been successfully treated with quinidine for atrial fibrillation for 4 years, but developed cardiac arrest due to recurrent PVT when quinidine was reinitiated for treatment of atrial fibrillation 3 months after successful cardiac surgery. No other drug was used, nor was an electrolyte abnormality detected at the time of PVT. Short-term therapy of drug-induced PVT. The results of short-term therapy for control of drug-induced PVT detailed in table 2. Repeated intravenous bolus (50 are to 100 mg) infusions of lidocaine followed by infusions of 2 to 3 mg/min were initiated in 21 patients. Cessation of administration of the offending drug and the use of lidocaine resulted in complete suppression of PVT in nine and possible suppression of PVT in three patients (Nos. 6, 17, 26) and was ineffective in 12 patients. Temporary atrial (four patients) or ventricular pacing (nine patients) was initiated for those suffering hemodynamically unstable episodes of PVT. The rate of pacing was initially adjusted (90 to 1 10/min) to control episodes of PVT and it was gradually decreased over a 3 day observation period. Temporary cardiac pacing proved completely effective in 11 patients (figure 1; table 2), while two patients (Nos. 25, 26) experienced breakthrough PVT when the rate of pacing was decreased but responded to an increased rate. The patients responded to cardiac pacing regardless of whether the baseline QT interval was normal or prolonged. Intravenous bretylium was used in three and was associated with increased frequency of PVT TABLE 3 Patients with miscellaneous causes of PVT K+ level Patient Age (yr)/ Sex No. Organic heart disease Metabolic-electrolyte 34/M Alcoholic cardiomyopathy 28 68/M None 29 30 59/M None 63/F None 31 Exercise-induced 34/M None 32 15/F Ebstein's anomaly 33 34 53/M Arrhythmogenic RV dysplasia 42/M None 35 Ischemic heart disease 61/M CAD 36 50/M CAD 37 58/M CAD 38 Bradyarrhythmia 51/F Hypertension 39 59/F 40 MVP and myocardiopathy 41 69/F Cardiomyopathy 74/F CHF, COPD 42 71/F CHF, COPD 43 44 25/F MVP 32/F MVP 45 Active Before arrhythmia discharge Failed (meq/l)A QT QTc QT QTc 2.6 2.6 Mg++ = 1.1 Ca++=7.9 3.0 0.40 0.36 0.46 0.43 0.36 0.48 0.46 0.45 P, Pr 0.56 0.60 0.52 0.58 0.48 0.46 0.56 Q, P, B 0.44 K+ replacement K' and Mg++ replacement Ca++ replacement K+ replacement 4.5 4.1 4.3 4.3 0.34 0.42 0.44 0.39 0.40 0.44 0.48 0.39 0.44 0.60 0.44 0.44 0.40 0.54 0.40 0.38 Nadolol Nadolol + verapamil Nadolol Atenolol - 0.40 0.36 0.38 0.46 0.42 0.40 0.44 0.36 0.44 0.49 Q, P, B 0.46 P 0.46 P, B Amiodarone, phenytoin 0.44 0.44 0.52 0.49 Paced Paced P, D, B 0.36 PacedB 0.36 0.40 0.50 0.46 0.42 Paced PacedB 0.36 0.48 4.2 3.8 3.5 3.8 4.1 4.0 3.3 0.40 0.40 0.55 treatment Long-term treatment Amiodarone Amiodarone Pennanent pacing 0.42 Ph. Q, P Q, P 0.42 0.55 D, P, T Permanent pacing Amiodarone, AICD No drugs Paced at 85 bpm Atenolol Nadolol B = bretylium; CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD chronic obstruction lung disease; D = disopyramide; MVP = mitral valve prolapse; Ph = phenytoin; Pr = propranolol; Q = quinidine; RV - right ventricular; T = tenormin. AAt the time of arrhythmia. "Permanent pacing. Vol. 74, No. 2, August 1986 343 NGUYEN et al. Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 FIGURE 1. Electrocardiographic strips from a patient (No. 18) with procainamide-induced PVT. Top, PVT is initiated after a long-short sequence. Middle, PVT was terminated by a direct-current external shock. The rhythm stabilized after initiation of ventricular pacing at 100 beats/min (bottom). whether used singly (patients 7 and 25) or with phenytoin (patient 20). Therapy with class IA antiarrhythmic agents was initiated 18 to 48 hr after the last recorded episode of PVT in 12 patients. PVT either recurred or increased in frequency in 10. Two patients (Nos. 8 and 12) developed PVT in association with quinidine but responded to procainamide (one patient) and disopyramide (one patient). Both the QT and QTc for these two patients were clearly prolonged. One patient (No. 6) received a bolus infusion of intravenous amiodarone (5 mg/kg) followed by an infusion of 1 g over 24 hr, which resulted in PVT control. None of these patients received intravenous Mg + or isoproterenol. Among the three patients who developed PVT while taking amiodarone, associated hypokalemia was found in one and bradyarrhythmias were found in two. The patients were treated with phenytoin (three patients), K' replacement (one patient), or long-term cardiac pacing (two patients). Long-term antiarrhythmic treatment. Long-term antiarrhythmic therapy was discontinued in eight patients because the original indication for its use was marginal. Seven patients were treated with digitalis, verap- FIGURE 2. Patient (No. 15) with quinidine-induced PVT shows an unusual pattern of arrhythmia initiation for patients with drug-induced PVT in that no preceding long-short sequence was recorded. 344 CIRCULATION THERAPY AND PREVENTION-VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 amil, 13-blockers, or phenytoin for control of symptomatic premature ventricular complexes or for rate control (for those with atrial fibrillation). Long-term therapy with amiodarone was used for control of the original arrhythmia in 12 patients. Two patients (Nos. 8 and 12) were. treated over the long term with procainamide and disopyramide for control of ventricular tachycardia and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, respectively. QT interval. The QT and QTc recorded from at least two 12-lead electrocardiograms between episodes of PVT ranged from 0.40 to 0.68 and 0.42 to 0.66 sec, respectively. The QT exceeded 0.48 sec in 10 of the 27 patients. There was no significant change in either the QT (0.40 + 0.08 sec) or QTc (0.50 + 0.60 sec) measured before or between interludes of PVT compared with those recorded (0.45 + 0.05 and 0.48 + 0.30 sec) in patients on long-term therapy. The QT interval between episodes of PVT ranged from 0.40 to 0.48 sec in eight of the 13 patients who underwent cardiac pacing, while the QTc ranged from 0.40 to 0.48 sec in four of the 13. Of note is the fact that 12 patients who developed drug-induced PVT responded to long-term amiodarone therapy, often in spite of further prolongation of the QT interval. Follow-up data. The follow-up data are recorded in table 2. Four patients died during a mean follow-up interval of 19 13 months. Two patients treated with amiodarone died: one (No. 11) died suddenly 1 month after hospital discharge and one (No. 15) died of amiodarone pulmonary toxicity 7 months after discharge. One patient (No. 14) who was not receiving antiarrhythmic drugs died suddenly 6 months after hospital discharge. One patient (No. 25) died of congestive heart failure 25 months after discharge. The remaining patients are alive and free of symptomatic arrhythmias. Repeated 24 hr ambulatory electrocardiographic recordings were available for all patients treated with long-term amiodarone therapy and for seven of the remaining patients with drug-induced PVT. None of these follow-up recordings showed PVT. tinued. Only one other patient in this category had a prolonged QT interval, and this interval remained prolonged even after Ca+ + repletion. In all four patients, PVT responded to correction of the abnormality. Exercise-induced PVT Four patients had PVT that was associated with exercise: two had no organic heart disease, another had Ebstein's anomaly associated with mitral and tricuspid prolapse, and a third had arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. The control QT interval was normal for each patient, but became abnormally prolonged in one after therapy with ,3-blockers. All of these patients responded to /3blockers alone or in combination with verapamil. Acute myocardial infarction - cardiomyopathy. Three patients developed PVT after acute myocardial infarction (Nos. 36, 37, and 38) and all showed a variable spontaneous cycle length preceding initiation of PVT (figure 3). These patients were treated with nitrates, /blockers, and type I drugs, but all required amiodarone for arrhythmia control. Two patients with bradycardiarelated PVT responded to penranent cardiac pacing and two patients with severe congestive heart failure and chronic lung disease responded to treatment of the underlying condition. One patient with cardiomyopathy had a history of recurrent syncope and documented cardiac arrest (PVT degenerating to ventricular fibrillation). Twenty four-hour Holter recordings showed recurrent episodes of PVT. She was treated with amiodarone and an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) was implanted. Over a follow-up period of 12 months, she has been without syncope and without discharge of her AICD. Prior drug trials with type LA antiarrhythmic agents for patients in the miscellaneous cause category (table 3) proved either ineffective or resulted in aggravation of the arrhythmia. This occurred whether the QT interval was normal or prolonged. Over a follow-up interval of 18 + 9 months in the miscellaneous cause group, two patients (Nos. 42, 43) died of congestive heart failure. Patients treated with amiodarone or ,8-blockers remain arrhythmia free. Miscellaneous causes of PVT Electrolyte abnormalities. In four patients, PVT was associated with abnormal low levels of serum K', Mg+ +, or Ca + (table 3). In one patient (No. 31), the arrhythmia was probably due to thioridazine and hypokalemia. She had been treated with thioridazine for 4 years and developed PVT only after initiation of diuretic therapy, which resulted in hypokalemia. Her QT and QTc were prolonged at the time of PVT, but these intervals returned to baseline values when her potassium levels were corrected and her thioridazine discon- Discussion Previous authors have emphasized the clinical importance of diagnosing torsade de pointes. This arrhythmia is diagnosed when the following features are present: (1) paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia during which the rhythm is irregular with rates of 200 to 250 beats/min, (2) progressive changes in amplitude and polarity of the QRS complexes such that the QRS axis changes and the complexes appear to be twisting around the isoelectric baseline, (3) spontaneous termi- Vol. 74, No. 2, August 1986 345 NGUYEN et al. A~~ A .jT7 T ~ B C Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 0 FIGURE 3. Representative strips from a patient who developed PVT after acute myocardial infarction. A, Normal QT interval (0. 30 sec) and heart rate (75 beats/min). B to D, Varying patterns of initiating sequences of PVT. PVT is initiated by progressive cycle length shortening in B, long-short sequence in C, and during sinus rhythm at rate of 72 beats/min in D. nation of most episodes, (4) occasional progression of the arrhythmia to sustained unimorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, and (5) a prolonged QT interval. In this report, we chose the more general term PVT (as suggested by Sclarovsky et al.10) for three reasons: (1) In many instances, it proved impossible to be certain whether the arrhythmia showed the characteristic pattern of twisting around the isoelectric baseline. (2) In some instances, a typical pattern of twisting around the baseline was associated with a normal QT interval. (3) In others, a long QT was associated with a polymorphous configuration that was clearly not characterized by twisting of the QRS complexes around the isoelectric baseline. It has been emphasized that those with classic torsade de pointes tend to respond to maneuvers that shorten the QT (i.e., cardiac pacing or isoproterenol infusion).3 5,6 In contrast, those with PVT and a normal QT are thought to respond to conventional type I antiarrhythmic drugs.3 In addition, one report suggests that those patients with drug-induced torsade de pointes show markedly prolonged QT intervals (> 0.6 sec).6 Our data suggest that the above formulation may not be relevant for the majority of patients presenting 346 with drug-induced PVT. We found that in the majority of patients with PVT the tachycardia was drug induced and that the QT interval was of limited value in deciding on proper therapy for these patients. For example, only three patients with drug-induced PVT showed QT prolongation of greater than 0.60 sec, suggesting that this criterion is not applicable in the diagnosis of druginduced PVT. In addition, six patients with drug-induced PVT and normal (or slightly prolonged) QT intervals failed to respond to other type I antiarrhythmic agents. Furthermore, temporary cardiac pacing proved effective regardless of whether the QT was normal or prolonged. Finally, two patients (Nos. 8 and 12) with clearly prolonged QT intervals who had quinidine-induced PVT responded to procainamide (one patient) and disopyramide (one patient). These data suggest that recognition of the PVT pattern as described (see Materials and methods) is crucial in arriving at proper therapy, while the absolute or corrected QT is of limited value. Reports by Denes et al. ` and Kay et al. 12 emphasize the consistent finding of a pause that precedes the onset of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Of interest was our finding that this same pattern was almost universally CIRCULATION THERAPY AND PREVENTION-VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 present in those with drug-induced PVT. This finding and the beneficial response to pacing may reflect a pathogenetic mechanism common to both torsade de pointes and PVT. Pause-related PVT was not a consistent finding in those with PVT unassociated with drugs. For example, in those with PVT associated with exercise, the arrhythmia became apparent only after a critical increase in sinus rate was achieved. Time elapsed from onset of drug therapy to PVT. An important finding in our study relates to the onset of PVT. One-half of the patients with type I drug-induced PVT (12 of 24) developed the tachycardia within 4 days of initiation of drug therapy. In eight, PVT developed weeks to years after initiation of the offending drug. In those with late-onset PVT, associated hypokalemia was found in two, bradycardia was noted in one, and in another patient PVT was observed after successful cardiac surgery for tricuspid valve replacement. As a group, these patients developed PVT while taking their regular dosage of medication. Drug blood levels were available for 17 patients and were found to be in the subtherapeutic or therapeutic range in 15 of the 17, suggesting that drug-induced PVT was an idiosyncratic response. Thus, a 4 day hospital stay for all patients initiated on type I antiarrhythmic drug therapy should be sufficient to detect a significant number of patients at risk for development of PVT. Similar findings have been reported in a prospective evaluation of quinidine therapy.'6 Miscellaneous causes of PVT. Torsade de pointes associated with electrolyte disorders, myocardial ischemia, and bradyarrhythmias has been described in previous reports.'7 21 Two of the four patients with electrolyte abnormalities (Nos. 30 and 31) exhibited a prolonged QT interval. In patient 30, the prolonged QT may have been due to the underlying cardiomyopathy since correction of the hypocalcemia (while associated with abatement of PVT) failed to normalize the QT interval. In the 10 patients with ischemic heart disease or bradyarrhythmia-related PVT, the QT was either normal or only slightly prolonged. Of particular interest are four patients with exercise-induced PVT. None of these patients had coronary artery disease but two had organic cardiac disease (Ebstein's anomaly in patient 33, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia in patient 34). The QT interval in these patients was either normal or borderline prolonged and each responded (as judged by repeated exercise treadmill testing) to ,3blockers alone or in combination with verapamil (patient 33). Exercise-induced "pleomorphic" ventricular tachycardia in the absence of coronary artery disease has been previously described.22,23 Vol. 74, No. 2, August 1986 Short-term therapy of PVT. Short-term treatment with intravenous lidocaine was associated with inconsistent benefit. This is in accord with the results reported by others for therapy of torsade de pointes. 2' '3 However, it is often unclear whether a "positive" response to lidocaine is in fact drug related or due to other therapy applied (i.e., discontinuation of offending drugs, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, or pacing). We found (as has been emphasized by others with regard to treatment of classic torsade de pointes3' 5) that cardiac pacing was uniquely effective in the management of these patients. The response to cardiac pacing was, however, clearly unrelated to whether the QT was prolonged or not. We found that use of other type I antiarrhythmic agents in patients with drug-induced PVT generally resulted in aggravation of the arrhythmia. While this would appear to be predictable, we are unaware of any previous reports documenting this finding for patients with drug-induced PVT. In addition, bretylium was also associated with arrhythmia aggravation in three patients (Nos. 7, 20, and 25). Long-term therapy for the original arrhythmia. Longterm amiodarone was initiated for control of the original arrhythmia in 12 patients with type I drug-induced PVT. Long-term follow-up of this group revealed that the arrhythmia was controlled in all, but one patient died suddenly 1 month after discharge from the hospital. While our findings suggest that long-term therapy with amiodarone is not proarrhythmic in those with type I drug-induced PVT, it should be emphasized that amiodarone itself may cause PVT.'4 The exact incidence of PVT due to amiodarone is not known, but appears to be very low. In our total series of 460 patients treated with amiodarone, only three instances (0.7%) of PVT were recorded. It should be emphasized that the 0.7% incidence of PVT is a minimal figure. The overall incidence of sudden death in our experience for patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias treated with amiodarone is 8%,'5 and the type of arrhythmia responsible for the sudden demise is not known. QT interval and PVT. The role of the QT interval in patients with PVT remains uncertain for several reasons. First, precise measurement of the QT interval (even from 12-lead electrocardiographic tracings) will at times be difficult and the precise upper limits of normal and the suggested corrections of the QT interval for rate are controversial.24 In patients with druginduced PVT, the issue is further compounded by the inherent QT interval-lengthening effects of class I or psychotropic agents. In our own report, for example, the QT intervals for the bulk of patients with drug347 NGUYEN et al. OT duration A 0,70 - 0,65 0,60 0 Cj 0,55 0,50 0 0 0,45 0,40 U03: - 0,50 0,60 0,70 0,80 0,90 1;00 1,10 Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 R-R INTERVAL 1,20 sec FIGURE 4. The effects of quinidine on the QT interval in 20 patients treated with this drug. The QT interval in seconds is displayed on the ordinate while the spontaneous sinus cycle length is shown on the abscissa. The QT interval varied from 0.35 to 0.62 sec. Four patients who developed ventricular arrhythmias are represented by ringed circles. Note that the QT interval proved to be an insensitive guide for predicting development of PVT. In addition, in the group of patients who did not develop ventricular arrhythmias, the QT interval fell between 0.40 to 0.48 sec. These data were kindly provided by Drs. Orinius and Ejvinsson. induced PVT fell into the range expected for those treated with type I agents but who never experienced PVT* (figure 4). For this reason, in our study, those patients with drug-induced PVT were not considered to have a clearly prolonged QT interval unless this interval exceeded 0.48 sec. Moreover, our data suggest that the QT interval cannot be used as a reliable guide for deciding on short- or long-term antiarrhythmic therapy in patients with PVT because (1) most patients with drug-induced PVT and a normal QT failed to respond to other type I drugs, (2) cardiac pacing was almost universally effective regardless of the QT interval, and (3) long-term therapy with amiodarone proved effective in patients with type I drug-induced PVT and this therapy was usually associated with further lengthening of the QT interval. Clinical implications. The most important finding of our study was that PVT, whether associated with normal or slightly prolonged QT intervals, was usually drug induced. Drug-induced PVT was almost always preceded by sinus bradycardia or a pause, while this *Orinius E: Personal communication. 348 finding was much less consistent in those with PVT that was not drug related. We suspect that some of the patients with drug-induced PVT were treated with other type I agents, in part because either the QT interval was normal or the characteristic pattern of twisting of the QRS around an isoelectric line was not present. We therefore believe that the critical element in the proper management of these patients is recognition of the PVT pattern. Intravenous lidocaine was inconsistently effective. Intravenous bretylium was ineffective and probably proarrhythmic, while cardiac pacing was almost universally effective in arrhythmia control, regardless of the QT interval. A 4 day hospital stay would be expected to detect approximately half of patients susceptible to type I drug-induced PVT. In addition, other possible aggravating causes, such as occurrence of bradyarrhythmia, electrolyte disorders, use of diuretic agents, or cardiac surgery should be evaluated. Our preliminary findings suggest that amiodarone may prove to be a suitable therapeutic option for longterm control of the original arrhythmia in patients with drug-induced PVT. References 1. Akhtar M, Brugada P, Henthorn RW, Scheinman MM, Waldo AL, Ward DE, Wellens HJJ: The minimally appropriate electrophysiologic study for the initial assessment of patients with documented sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. PACE 8: 918, 1985 2. Smith W, Gallagher J: "Les torsades de pointes": an unusual ventricular arrhythmia. Ann Intern Med 93: 578, 1980 3. Soffer J, Dreifus LS, Michelson EL: Polymorphous ventricular tachycardia associated with normal and long Q-T interval. Am J Cardiol 49: 2021, 1982 4. Krikler DM, Curry PVL: Torsade de pointes, an atypical ventricular tachycardia. Br Heart J 38: 117, 1976 5. Tzivoni D, Keren A, Stern S: Torsade de pointes versus polymorphous ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 52: 639, 1983 6. Keren A, Tzivoni D, Gavish A, Levi J, Gotlieb S, Benhorin J, Stern S: Etiology, warning signs of therapy of Torsades de Pointes: a study of 10 patients. Circulation 64: 1167, 1981 7. Schweitzer P, Mark H: Delayed repolarization syndrome. Am J Med 75: 373, 1983 8. Bhandari AK, Shapiro WA, Morady F, Shen EN, Mason J, Scheinman MM: Electrophysiologic testing in patients with the long QT syndrome. Circulation 71: 63, 1985 9. Lepeschkin E: The U wave of the electrocardiogram. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis 38: 39, 1969 10. Sclarovsky S, Strasberg B, Lewin RF, Agmon J: Polymorphous ventricular tachycardia: clinical features and treatment. Am J Cardiol 44: 339, 1979 11. Denes P, Gabster A, Huang SK: Clinical electrocardiographic and follow-up observations in patients having ventricular fibrillation during Holter monitoring. Role of quinidine therapy. Am J Cardiol 48: 9, 1981 12. Kay GN, Plumb VJ, Ariciniegas JG, Henthorn RW, Waldo AL: Torsade de Pointes: the long-short initiating sequence and other clinical features. Observations in 32 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2: 806, 1983 13. Lyon LJ: Lidocaine for quinidine-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Chest 75: 103, 1979 (letter) 14. Sclarovsky S, Lewin RF, Kracoff 0, Strasberg B, Arditti A, Agmon J: Amiodarone-induced polymorphous ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J 105: 6, 1983 15. Eldar M, Sauve MJ, Abbott JA, Ruder MA, Scheinman MM: CIRCULATION THERAPY AND PREVENTION-VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. Aborted sudden death: long-term follow-up. Circulation 72(suppl III): 111-44, 1985 Ejvinsson G, Orinius E: Prodromal ventricular premature beats preceded by a diastolic wave. Acta Med Scand 208: 445, 1980 Topol EJ, Lerman BB: Hypomagnesemic torsade de pointes. Am J Cardiol 52: 1367, 1983 Curry P, Fitchett D, Stubbs W, Krikler D: Ventricular arrhythmias and hypokalemia. Lancet 2: 231, 1976 Khan MM, Logan KR, McComb JM, Adgey AAJ: Management of recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with QT prolongation. Am J Cardiol 47: 1301, 1981 Taylor GJ, Crampton RS, Gibson RS, Stebbins PT, Waldman MTG, Baller GA: Prolonged QT interval at onset of acute myocar- 21. 22. 23. 24. dial infarction in predicting early phase ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J 102: 16, 1981 Cokkinos DV, Mallios C, Philiar N, Norides EM: "Torsade de Pointes:" a distinctive entity of ventricular arrhythmia. Acta Cardiol 33: 167, 1978 Woelfel A, Foster JR, Simpson RJ, Gettes LS: Reproducibility and treatment of exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 53: 751, 1984 Woelfel A, Foster JR, McAllister RG Jr, Simpson RJ Jr, Gettes LS: Efficacy of verapamil in exercise-induced ventricular techycardia. Am J Cardiol 56: 292, 1985 Surawicz B, Knoebel SB: Long QT: good, bad or indifferent? J Am Coll Cardiol 4: 398, 1984 Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Vol. 74, No. 2, August 1986 349 Polymorphous ventricular tachycardia: clinical characterization, therapy, and the QT interval. P T Nguyen, M M Scheinman and J Seger Downloaded from http://circ.ahajournals.org/ by guest on June 18, 2017 Circulation. 1986;74:340-349 doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.74.2.340 Circulation is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 1986 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online ISSN: 1524-4539 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/74/2/340 Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Circulation can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Circulation is online at: http://circ.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/