* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Play your part in managing syphilis

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

HIV and pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

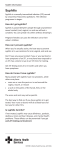

The Pharmaceutical Journal 263 cpd Play your part in managing syphilis Syphilis is not a disease of the past. Cases in the UK have been rising. This article gives an overview of the disease and its treatment and discusses what pharmacists can do LUCY HEDLEY PGDIPGPP, MRPHARMS, ROTATIONAL CLINICAL PHARMACIST, AND PREET PANESAR DIPCLINPHARM, MRPHARMS, LEAD PHARMACIST, MICROBIOLOGY, UCLH NHS FOUNDATION TRUST Reflect SYPHILIS is a predominantly sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochaete bacterium Treponema pallidum. In the early stages the disease is usually easily treatable but not all of those infected experience symptoms and, if untreated, serious complications, including blindness, stroke, aortic aneurysm and paralysis, can arise. Evaluate Plan Act REFLECT Numbers The World Health Organization estimates that around 12 million new cases of syphilis occur worldwide every year. The bulk (eight million) of these are in south-east Asia and subSaharan Africa but high rates are also observed in central Asia and eastern Europe.1 In western Europe the WHO estimates there are 140,000 new cases of syphilis each year and diagnosis has risen substantially in the past decade in the UK. In 2007, 3,762 diagnoses of infectious syphilis were made — more than in any other year since 1950.2 There was a slight decrease in 2010 but by last year cases of infectious syphilis had increased by 10 per cent.3 The prevalence of new infections is significantly greater in men than in women, with men accounting for 90 per cent of new diagnoses.3 In the UK syphilis is largely concentrated among men who have sex with men (MSM) — where sexual orientation was recorded in male cases, 75 per cent of diagnoses was among this group. MSM syphilis diagnoses in England increased by 28 per cent from 2010 to 2011. A number of factors are likely to have contributed to this sharp rise. 1 What are the symptoms of syphilis? 2 What are the treatment options? 3 What role can pharmacists play in the management of syphilis? Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. Left: primary syphilis chancre DR MA ANSARY/SPL ; Above: secondary syphilis rash MARTIN M ROTKER/SPL Use of inaccurate syphilis tests during 2011 may have led to some patients being incorrectly diagnosed with syphilis, although this is likely to have only marginally increased the numbers. Reporting of sexual orientation has improved in recent years, leading to a greater number of diagnoses being assigned to MSM than previously.3 A significant proportion of STI diagnoses among MSM continue to be in the younger age groups and 14 per cent of syphilis cases are in those aged between 15 and 24 years of age.3 In England there was an 85 per cent increase in the numbers of new diagnoses of primary, secondary and early latent syphilis in genitourinary medicine clinics between 2002 and 2011.3 This rise has been attributed to a number of local outbreaks, the largest of which was in London between 2001 and 2004.2 Transmission and risks KEY POINTS is a disease that has • Syphilis serious consequences if • undiagnosed and untreated. Pharmacists can help slow the increase in cases in the UK be being aware of the disease symptoms and promoting good sexual health. T pallidum is a human pathogen that does not naturally appear in other species. Transmission is by penetration of through mucous membranes by the spirochaete or through abrasions on epithelial surfaces. This usually occurs by direct contact with an infectious lesion or skin rash, (eg, during sexual contact) but visible sores or rash are not necessary for transmission. The person remains sexually infectious until about two years after secondary syphilis (see later) has cleared. The infection can also be transmitted in pregnancy (vertical transmission) or via infected blood products. T pallidum cannot survive drying or exposure to disinfectants, so fomite transmission (eg, from toilet seats) is almost impossible. Patients should be advised to refrain from sexual contact of any kind until the results of the first follow-up blood tests confirm they are clear of infection.4 Those with lesions (Vol 289) 8 September 2012 www.pjonline.com 264 The Pharmaceutical Journal cpd should also wait until these are fully healed. Unprotected sex, promiscuous sex and intravenous drug use are the major risk factors for transmission of syphilis. Ongoing high levels of high-risk sexual behaviour have probably contributed to the rise of the disease in MSM and this group remains a priority for targeted STI prevention and health promotion work. Because it causes genital ulcers, syphilis is associated with an increased risk of HIV transmission and acquisition. Co-infection is common in those with syphilis (27 per cent).2 As the number of syphilis cases in women of reproductive age has grown this has resulted in an increase in cases of congenital infection.1 Healthcare workers are at potential risk of transmission through needlestick injuries or contact with lesions. Late syphilis Early syphilis Primary syphilis Chancre(s) Secondary followed by syphilis lymphoedema Rash, fever, lymphoedema, Early latent syphilis sore throat, malaise, weight loss, hair loss, headaches Late latent syphilis No symptoms Tertiary syphilis Gummatous syphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis 0 3 months 2 years Figure 1: Progression of acquired syphilis without treatment PANEL 1: CLINICAL FEATURES OF TERTIARY SYPHILIS Gummatous syphilis Timing after infection 1–46 years (average 15 years) Cardiovascular syphilis 10–30 years Neurosyphilis Early Late (4–25 years) Signs and symptoms Formation of chronic gummas, which are soft, tumour-like balls of inflammation that vary in size. Gummas can occur anywhere but commonly affect the skin and bones (often below the knee) and can cause bone pain. They may also grow on organs. Stages and symptoms Syphilis is classified as acquired or congenital. Acquired syphilis is divided into early and late disease. Early acquired syphilis can be further subdivided into primary, secondary and early latent (less than two years of infection) disease and late acquired syphilis can be subdivided into late latent (over two years of infection) and tertiary (including gummatous, cardiovascular and neurological) disease. Figure 1 provides a summary. Congenital syphilis is also divided into early and late disease, diagnosed in the first two years of life and presenting after two years of disease,1 respectively. Syphilis was famously referred to as “the great imitator” by Sir William Osler because of its varied presentations, which are similar to many other conditions. Acquired syphilis Primary syphilis4–6 is usually characterised by the appearance of a single skin lesion (called a chancre) which is typically firm, small, round and painless, occurring at the point of contact with the infectious lesion(s) of another person. However, chancres may also be multiple, painful and purulent. They do not have to be genital. For example, they may appear on the lips or in the mouth (see image 8 September 2012 (Vol 289) www.pjonline.com Inflammation around the aorta, resulting in aneurysm formation and aortic valve dilation, leading to heart failure and heart attacks. Loss of mental and physical function, including changes in mood and personality. Early neurosyphilis can be asymptomatic or present as meningitis. Late neurosyphilis appears as meningovascular syphilis, general paresis or tabes dorsalis (inflammation of spinal dorsal column), which is associated with poor balance and lightning pains in the lower extremities. Adapted from National guidelines on the management of syphilis 20084 on p263). Multiple lesions are more common when a patient is co-infected with HIV. The time from initial exposure to start of initial symptoms can range from 10 to 90 days (average 21 days). Swelling (lymphoedema) frequently occurs (80 per cent) around the area of infection, usually seven to 10 days after chancre formation. The chancre lasts three to six weeks without treatment. Untreated, primary syphilis will always progress to secondary syphilis. This occurs four to 10 weeks after first exposure.4,6,8 Secondary syphilis typically involves the skin, mucous membranes and lymph nodes. There is often a symmetrical, reddish brown rash on the trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles of the feet (see image on p263). The rash is classically non-itchy but can be itchy, particularly in darkskinned patients. It may become maculopapular or pustular and form wart-like lesions (known as condylomata lata) on mucous membranes. Other symptoms can include fever, lymphoedema, sore throat, malaise, weight loss, hair loss and headaches. The acute symptoms usually resolve after six weeks, but about 25 per cent of people experience a recurrence of secondary symptoms. Latent syphilis4,9 (both early latent and late latent) has no signs and symptoms and can last for years. The distinction between early latent and late latent is for treatment purposes (see later). It is difficult to tell exactly how long someone has had the infection, but serological tests and medical and sexual histories can help clinicians make a good estimate. In around a third of cases tertiary (or late symptomatic) syphilis4,6 can occur three to 15 years after infection. It can The Pharmaceutical Journal 265 cpd PANEL 2: TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR DIFFERENT STAGES OF SYPHILIS Clinical stage Recommended regimens Early syphilis (primary, secondary and early latent) Benzathine penicillin 2.4MU IM (single dose) Doxycycline 100mg po bd for 14 days Procaine penicillin 600,000units IM od for Azithromycin 2g po stat or 500mg od 10 days for 10 days Erythromycin 500mg po qds for 14 days Ceftriaxone 500mg IM od for 10 days Amoxicillin 500mg PO qds plus probenecid* 500mg qds for 14 days Late latent, cardiovascular or gummatous syphilis† Benzathine penicillin 2.4MU IM weekly (three doses) Procaine penicillin 600,000units IM od for 17 days Alternative regimens Doxycycline 100mg po bd for 28 days Amoxicillin 2g po tds plus probenecid 500mg qds for 28 days Neurosyphilis, including Benzylpenicillin 18–24MU od in divided neurological/ophthalmic doses for 17 days involvement in early syphilis Procaine penicillin 1.8–2.4MU IM od plus probenecid 500mg po qds for 17 days Doxycycline 200mg po bd for 28 days Amoxicillin 2g po tds plus probenecid 500mg po qds for 28 days Ceftriaxone 2g IM or IV for 10–14 days Early syphilis in pregnancy‡ In the first or second trimester, benzathine penicillin 2.4MU IM (single dose) but where treatment is given in the third trimester a second dose should be given after a week Procaine penicillin 600,000units IM od for for 10 days Amoxicillin 500mg po qds plus probenecid 500mg po qds for 14 days Erythromycin 500mg po qds for14 days Ceftriaxone 500mg IM od for 10 days Azithromycin 500mg po od for 10 days Late syphilis in pregnancy Manage as in non-pregnant patients but without doxycycline Congenital syphilis§ Benzylpenicillin sodium 100,000–150,000 units/kg IV daily (in divided doses given as 50,000units/kg 12 hourly in the first seven days of life and eight hourly thereafter) for 10 days Procaine penicillin 50,000units/kg IM od for 10 days *Probenecid increases serum concentration of the antibiotic (patients are unable to tolerate very large antibiotic doses due to adverse effects); †Steroid cover should be used when treating cardiovascular syphilis; ‡ Management should be in close liaison with obstetric, midwifery and paediatric teams. Appropriate follow-up is required after birth; § In children, IV therapy may be preferred rather than intramuscular injections, which are painful. present as gummatous syphilis (15 per cent), cardiovascular syphilis (10 per cent) or neurosyphilis (6.5 per cent), which are described in Panel 1. Congenital syphilis Infection with congenital syphilis1, 10 can occur during pregnancy or at birth. If the baby is infected during pregnancy and is untreated, there is a high risk of stillbirth, prematurity or neonatal death. If infected during delivery, the baby will develop a number of symptoms over time. Two-thirds of syphilitic infants are born without signs of the disease. Early congenital syphilis develops over the first two years of life and common symptoms include hepatosplenomegaly (70 per cent), rash (70 per cent), fever (40 per cent), neurosyphilis (20 per cent) and pneumonitis (20 per cent). Left untreated, late congenital syphilis occurs in 40 per cent of babies. Symptoms include saddle nose deformation (loss of height of nose due to collapse of the bridge), Higoumenakis sign (unilateral enlargement of the sternoclavicular portion of the clavicle), saber shin (malformation of tibia) and Clutton’s joints (symmetrical joint swelling). Congenital syphilis kills more than a million babies a year worldwide but is preventable if infected mothers are identified early and treated appropriately.7 The World Development Report cites antenatal screening and treatment for syphilis as one of the most cost-effective health interventions available. In The authors will be available to answer questions on this topic until 24 September 2012 Ask the expert www.pjonline.com/expert England in 2005, 95 per cent of pregnant women were screened for syphilis, although uptake varied from 77 to 100 per cent between regions.2 Diagnosis and investigation Syphilis can be difficult to diagnose in the early stages. Confirmation is required with blood tests or direct visual microscopy.4,6,11 For all suspected cases a full sexual health screen, including HIV testing, should be performed. A thorough investigation should be undertaken for the clinical manifestations of syphilis, including full examinations of skin and mucosal surfaces, lymph nodes, cardiovascular and neurological systems. In addition, history of travel to or living in countries where syphilis or other treponemal infections are endemic should be established. In women an obstetric history, including potential complications such as still births and miscarriages, should be taken. Serological tests Blood tests are routine. They can be divided into treponemal and non-treponemal. Non-treponemal tests are used initially and include the venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test and rapid plasma reagin test. These are widely used for syphilis screening but falsepositive reactions can occur with viral infections (such as varicella and measles), autoimmune disorders, infections (such as malaria, tuberculosis, and endocarditis) and pregnancy. Treponemal specific tests detect antibodies to antigenic components of T pallidum. These tests are primarily used to confirm the diagnosis of syphilis in patients with a reactive nontreponemal test. They have sensitivities and specificities equal to or higher than nontreponemal tests but are more difficult and expensive, which limits their usefulness as screening tests. Direct testing Dark-field microscopy is the most specific technique for diagnosing syphilis when a chancre or condylomata are present. Serous exudate from the lesion is examined under a microscope equipped with a (Vol 289) 8 September 2012 www.pjonline.com 266 The Pharmaceutical Journal cpd Available online until 8 October 2012 Check your learning www.pjonline.com/expert dark-field condenser. T pallidum is identified by its characteristic corkscrew appearance. Direct fluorescent testing can also be done on samples from the lesions using antibodies tagged with fluorescein, which attach to specific syphilis proteins. Another test is nucleic acid amplification to detect the presence of specific syphilis genes. Treatment Syphilis is curable when identified early — a single dose of penicillin is sufficient to cure the infection in those with primary, secondary or early latent disease. Additional doses will be required in those who have had the disease for longer. Although treatment kills the bacterium and prevents further damage, it will not repair damage already done. And in cardiovascular syphilis, lesions can progress despite treatment. Panel 2 summarises the treatment regimens for different stages of the disease, including alternative regimens.4 Both benzathine- and procainepenicillin are unlicensed in the UK, probably due to low demand. They are given by injection into a large muscle. The gluteal muscle is usually preferred because the injection is least painful. Prescribers should be aware of the uses and actions of these products and be assured of their quality and source. Reactions to treatment Penicillin is the gold standard treatment — other antibiotics are not as efficacious and failures have been reported in the literature. However, penicillin is the most common cause of anaphylaxis, and facilities for appropriate treatment should be available. Patients should be monitored for immediate adverse reactions for 15 minutes after receiving their first injection. In addition they should be advised to seek urgent medical attention if they later experience shortness of breath, itchy wheals on their 8 September 2012 (Vol 289) www.pjonline.com skin, facial swelling or tightness in their chest or throat. Penicillin desensitisation may be considered for patients reporting penicillin allergy. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness with headache, myalgia, chills and rigors that resolves within 24 hours. It is common in the treatment of patients with early syphilis (a figure of 50 per cent has been reported) but is usually not important unless there is neurological or ophthalmic involvement, or in pregnancy when it may cause fetal distress and premature labour. The reaction is thought to occur as a result of destruction of spirochetes and activation of a pro-inflammatory cytokine cascade. It is uncommon in late syphilis but can potentially be life threatening if there is involvement of coronary ostia, the larynx or the nervous system. Steroids are recommended when there is neurological or cardiovascular involvement and may also be used in pregnancy (additional fetal monitoring is required). Procaine psychosis Inadvertent intravenous injection of procaine penicillin can result in a reaction characterised by fear of impending death and may cause hallucinations or fits immediately after injection, lasting less than 20 minutes. Calm and verbal reassurance is required, and diazepam can be used if fits occur. A single dose of penicillin is sufficient to cure the infection in those with primary, secondary or early latent disease Resources British Association for • The Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) website (www.bashh.org) has links to various guidelines for sexually transmitted infections. Role for pharmacists Pharmacists, especially those working in community settings, are in a prime position to provide advice and signpost people to sexual health services. For example, women coming into the pharmacy requesting emergency contraception should always be advised that this does not protect against the risks of STIs and be referred for screening where appropriate. Emergency contraception consultations are also ideal opportunities to engage patients in discussions about future, more appropriate methods of contraception. People might also visit a pharmacy requesting products for lesions that could be PRACTICE POINTS Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the regulator will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio. 1. Emphasise to patients, where appropriate, the importance of compliance with their course of antibiotics and follow-up appointments. 2. Refer at-risk patients for sexual health screening. Consider making this activity one of your nine CPD entries this year. syphilitic. If syphilis cannot be excluded, these people should be referred to a GUM clinic or their GP. In hospitals patients may be seen on wards or, more likely, in an outpatient clinic where prescriptions will need screening. This will involve checking the appropriateness and duration of therapy and potential interactions, and titrating doses for renal or hepatic impairment. There is also an important role for pharmacists in counselling patients on their therapy, and discussing any compliance issues and the importance of completing the course and attending follow-up appointments for monitoring. Some patients may be prescribed long-term intravenous antibiotic courses. In such cases it is important to establish how the medicine will be prepared, how it will be administered and who will be administering it. This will require detailed discussions with the outpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy (OPAT) team, community nurses or homecare services. GUM clinics often have patient group directives for treatment of STIs and pharmacists are involved in the development of such services. Despite intensive efforts, the unusual nature of T pallidum has hindered progress towards the development of a vaccine to prevent infection.11 Good sexual health is a key component of the prevention of syphilis and pharmacists have a part to play in reinforcing this. In particular, people at risk should be encouraged to: barrier contraceptives • Use aware of the symptoms of • Be infection and seek early medical • advice Get tested regularly (Consulting clinical services regularly increases the chances that infection can be identified, even if there are no symptoms. HIV testing should be considered every three months to annually for patients in high-risk groups.) To avoid reinfection, partners of infected individuals should be advised to be screened and, if necessary, treated. References available online