* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Sectional Controversy and the Civil War

Survey

Document related concepts

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Lost Cause of the Confederacy wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

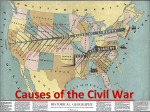

Sectional Controversy and the Civil War The United States developed along sectional lines. North • • primarily commercial and industrial and was dominated, both socioeconomically and politically by a banker-commercial-industrialentrepreneurial class. economy characterized by commerce and trade. South • • primarily an agrarian society governed by an aristocratic planter class. economy based on single-crop agricultural production. There existed between North and South sharp differences in terms of social life/social structure, political ideals, economic pursuits, cultural patterns, and value systems. • The sectional differences that developed between the North and the South had its origins in the Constitutional Convention. • Counting the South's slaves toward its population for purposes of determining apportionment in the House of Representatives led to the adoption of the three-fifths rule, a measure that would prove increasingly annoying to the North. • The goal of the founders, however, was to mute the sectional issue as much as possible by creating a balance in Congress between the North and the South. • From the beginning, however, there were indications that the effort was probably futile. • In 1793, less than six years after the adoption of the Constitution, Congress was compelled to address Southern complaints that escaped slaves were able to move freely throughout the North without fear of capture. • After much debate, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act (1793), which empowered federal marshals and magistrates to return runaway slaves to their owners. • Many Northern states passed laws almost immediately trying to block enforcement of the act. • Less than a decade had elapsed since the adoption of the Constitution, and already Congress was having difficulty addressing sectional issues in a way that was satisfactory to both sides. The issue of slavery Historian Joseph Ellis perceived the question of slavery as a “tragic and perhaps intractable problem that even the revolutionary generation with all its extraordinary talent, could neither solve nor face.” James Madison Convinced that slavery was an explosive topic that must be removed from the political agenda of the new nation… Believed that slavery was taboo because, more than any other controversy, it possessed the political potential to destroy the union. Wanted to take slavery off the national agenda because he believed that decisive action would result in the destruction of either the Virginia planter class or the nation itself. Benjamin Franklin Desired to put slavery onto the national agenda before it was too late to take decisive action in accord with the principles of the Revolution. Wanted to place slavery on the national agenda because he feared the window of opportunity for rendering the practice and institution of slavery extinct in America was shutting. Complicating the issue of slavery beyond its mere intense divisiveness was the apparent constitutional ambiguity surrounding it. On the one hand, slaves (although the precise term was not used) counted as threefifths of a person for the purpose of apportionment and the slave trade was both recognized and protected for at least twenty years. On the other hand, an impost was levied on the importation of slaves in order to discourage the infernal traffic and it was not indefinitely inviolable. To further complicate matters, the Declaration, which was no less authoritative than the Constitution as a founding document, universally declared that “all men are created equal.” True, one may argue what Jefferson’s notion of equality meant—still, the practice and institution of slavery seemed to repudiate this fundamental principle. In this particular case at least, the democratic ideals and principles of liberty, equality, and justice seemed incongruent with (and thus took a back seat to) union. • A few decades later, mediating sectional difficulties returned to the top of Congress' agenda. President Thomas Jefferson's decision to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 added a substantial amount of territory to the young nation, and both Northerners and Southerners wanted to claim it as part of their region. Allan Nevins in The Ordeal of the Union, asserted that the question of slavery was irrepressible. According to Nevins, “one section had to yield its fundamental position.” Schlesinger challenged those historians who argued the war was repressible to clarify what alternatives existed other than war. Cummins and White wrote: “[Schlesinger] posed the question: If the war could have been avoided, what course should American leaders have followed with respect to slavery?” Each of the supposed alternatives Schlesinger listed he rejected “as either inadequate or unattainable.” He noted how southern liberals were unable to bring slavery to an end in a single southern State. According to Schlesinger, the “moral issue of slavery and the future of the Negro in America” constituted the major cause of the war. He noted that asking northerners to turn a blind eye to the fact “the South…was a closed society” was equivalent to claiming “that there should have been no anti-Nazis during the 1930s.” According to Schlesinger, the “Civil War” was an irrepressible conflict insofar as “the moral issue of slavery was too profound to be solved by political compromise.” Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Missouri Compromise (1820) In 1819, the first of the newly organized states from the LA Purchase, Missouri, petitioned the federal government for entry into the Union as a slave state, which threatened to upset the balance of power between slave and non-slave states in the Senate. Representative James Tallmadge offered a bill that would have allowed Missouri into the Union with the stipulation that slavery be restricted there. Not surprisingly, the bill passed the Northern-controlled House but not the Senate. Finally, a compromise temporarily postponed the issue. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and stipulated that no slavery would be permitted in the Louisiana Purchase north of 36° 30' latitude. Thomas Jefferson In a letter to John Holmes dated April 22, 1820, Thomas Jefferson commented on slavery and the Missouri question (prior to the passage of the Missouri Compromise). In it, Jefferson compared efforts to reconcile differences over slavery to having “a wolf by the ear.” One caught in such a predicament would find it difficult (if not impossible) to either “hold him” or “safely let him go.” Among those who found it impossible to hold on were abolitionists and evangelicals who perceived it as an injustice. Among those who found it impossible to safely let it go were slaveholders, slavers, and planters guided by selfpreservation. Either option was dangerous…. Although a divisive controversy had been sidestepped, many Americans were shocked by the vehemence of the debates regarding slavery. In a letter written the same year as the Missouri Compromise, Jefferson warned that the conflict over the Missouri Compromise was a “firebell in the night,” heralding a major national crisis. Sectional compromises The persistent differences between North-South not only reemerged during times of political stress, but were exacerbated. In each case certain adjustments (i.e. concessions/ compromises) were made in order to placate or appease the other side. The problem was that with each adjustment, positions synthesized, crystallized, and hardened and neither side seemed as willing to accommodate the views, positions, and demands of the other. The Missouri Compromise was the first of several sectional compromises, but as time passed, keeping harmony between Northern and Southern interests became a much more complicated endeavor. Cummins and William Gee White wrote: “Increasingly, Congressional disputes over national policy pitted representatives from the North against those from the South. In each case, a sectional adjustment was eventually arranged and the crisis passed without serious incident. Still, bitterness grew and gradually diminished the possibility of further compromise. Despite strong ties….the North and South moved steadily apart….[and] compromise became more difficult to achieve than ever before…. no one appeared able to devise a formula that would preserve peace. “ • The slaveholding South could not live up (in practice) to the principles and ideals espoused in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Biblical belief that all humans were created equal in the image of God. • This was the slaveholders’ “dilemma” • An atypical response was if slavery was inconsistent with American principles, ideals, and morals, then abolish it. • A more typical response was that slaveholders could not give up their slaves because of self interest (i.e. there was a conflict between their values and their practice). • It became particularly evident by Calhoun’s time that due to the cotton gin and the profitability of the enterprise that slavery wasn’t going to die out. • This, in turn, meant that slavery was going to come under even sharper attacks by abolitionists. • While they could not give up their slaves, they still felt real bad about it (i.e. slavery was a “necessary evil”).. • Slaveholders both rationalized and justified slavery rather than subject it (and themselves) to disinterested and honest evaluation. • Southern slaveholders kept both their mistress and their morals by convincing themselves that the institution and practice was actually good for Africans because slaveholders introduced them to civilization—without slavery, African “savages” would destroy themselves (this argument became especially salient within the context of abolitionism). • Thus, slaveholders were motivated by self-interest; it was in their self-interest to think this way; their consiousness/rational thought was stupified by their self interest (i.e. they refused to recognize the evil in it). • Abolitionist agitation was one of the main influences on the extreme form of the sense of white superiority in America and African inferiority/savageness (and the need to discipline them). Gag rule on slavery When the American Anti-Slavery Society formed in 1833, it launched a petition campaign as one means of encouraging opposition to slavery and identifying specific areas in which Congress could act immediately to bring slavery to an eventual end. The petitions most frequently called on Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. As the number of antislavery petitions increased, Democrats enacted the first gag rule in 1836. The gag rule was a series of procedural rules designed to prevent the submission of antislavery petitions and was one of the principal tools employed by the Jacksonian Democrats to silence abolitionist agitation and maintain a political coalition with slaveholders. It provided that petitions relating to slavery would be laid on the table without being read or referred to committee. Supporters of the gag rule argued that the drafters of the Constitution had intended that the subject of slavery should never be discussed or debated in Congress. In this case, Congress failed to meet one of its important responsibilities—to resolve disputes. Serving as a Whig representative from Massachusetts, former president John Quincy Adams led the fight against the gag rule. Over nearly a decade he made opposition to and evasion of the rule a principal part of his legislative activities. Adams argued that the Democrats, in deference to the sensibilities of their slaveholding supporters, threatened to deny Americans basic civil rights since the Constitution guaranteed the right of citizens freely to petition their government. Adams's principled assault on the gag rule attracted new converts to the antislavery cause and his skillful evasions made the rule itself ineffective. In 1844 Congress lifted the rule and Adams's victory became one of the celebrated events of the abolitionist movement. Source: Sewell, Richard H. Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837–1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976. Nullification Crisis under Andrew Jackson At a Jefferson Day celebration, Jackson toasted, "Our Federal Union—it must be preserved." Calhoun responded, "The Union—next to our liberty most dear." South Carolina Exposition and Protest The South Carolina Exposition and Protest was written in 1828 by Vice President John C. Calhoun during the nullification crisis. The document was a protest against the tariff of 1828. It stated that if the tariff was not repealed, South Carolina would secede. It also stated Calhoun's Doctrine of nullification. I.e., The idea that a state has the right to reject federal law. On December 19, 1828, it was presented to the South Carolina State House of Representatives. It was not formally adopted by the legislature, nor did it affect the tariff, but a pamphlet of it was published and circulated. Since Calhoun was then Vice President, he was forced to conceal his authorship. South Carolina did adopt the nullification doctrine, nullifying the tarrifs and voting to build its own army. Webster-Hayne debates After the Tariff of 1828 was blamed for economic difficulties in South Carolina, Vice President John C. Calhoun presented a theory for states' rights whereby a state could nullify a federal law if the law was hazardous to the state. The arguments for and against nullification raged in the Senate during 1828-1829 and were furthered at the end of 1829 by a proposal to restrict the surveying and sale of federal land. In January 1830, in a series of famous debates lasting two weeks in which Senator Robert Y. Hayne (SC) faced off against Daniel Webster. The Webster-Hayne debate is generally regarded as one of the greatest congressional debates in history. During an ongoing argument about the constitutionality of nullification, Webster eloquently defended the Constitution and the Union and was thereafter regarded as a hero of nationalists. The debates defined the terms of the argument over the nature of the federal union that would persist for the next 30 years. Robert Y. Hayne • • • • • Hayne, who strongly endorsed the theory of states' rights, joined the debate on January 19, 1830. The doctrine of states’ rights appealed to both Westerners and Southerners • A leading Southern spokesman in the U.S. Senate during the 1830s for the right of states to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. elected to the U.S. Senate in 1822 and reelected to the Senate without opposition for a second term in 1828. In the Senate, Hayne focused on defeating efforts to implement high protective tariffs, which he deemed unwise and unconstitutional. Hayne argued that a broad interpretation opened the door to domination of the states by the federal government and, in the long run, the end of democracy. Hayne resigned from the Senate in 1832 to become the governor of South Carolina. As governor, he supported Henry Clay's compromise approach to dealing with the tariff issue and played a leading role in calming hostility toward the federal government in South Carolina (he left the governor’s chair in 1834). Daniel Webster • Webster introduced slavery into the argument in his speech on January 20th, seeking to divide Southern and Western interests. • In rebuttals over the course of the next week or so, Hayne defended not only the institution of slavery but also the doctrines of intervention and nullification, while Webster championed a more nationalistic view. Robert Y. Hayne • With Calhoun presiding over the Senate, on January 21 and 25, Hayne defended not only the institution of slavery but also the doctrines of intervention and nullification. • • • • • • • Webster's response was scheduled for the next day, and the Senate chamber was packed to hear the great orator. In his speech, Webster defended the existing Constitution against the doctrine of nullification. He opposed the theory that the Union had been created by the states, instead arguing that it had been created by the people. His language referring to the "people's government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people" would later be echoed in Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. Webster also argued that the states could not be the final judges of the constitutionality of measures they disapproved of, but that the U.S. Constitution was the supreme law of the land and that the U.S. Supreme Court, and not the states, had the final right to interpret it. In the finale to his speech, Webster refused to imagine the prospect of a divided Union but with poetry of language and sentiment, rallied support for the idea of a perpetual Union. Webster closed his speech with a call for "Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!" Daniel Webster's second reply to Robert Y. Hayne (January 26-27, 1830) • Thousands of copies of Webster's speech were reproduced and distributed throughout the nation. • Ever thereafter, Webster was the acknowledged spokesman for those who supported a nationalistic view of the Constitution, but his arguments, noble as they were, did little to convince states' rights supporters, who continued to make their arguments until the outbreak of the Civil War. • The Webster-Hayne debates stirred deep sentiments in both the North and the South. Compromise of 1850 When gold was discovered in California in 1848, Americans rushed to California by the tens of thousands. By late 1849, the population of California topped 100,000 (enough for California to be admitted as a state). It happened so fast that Californians did not have enough time to organize California as a territory. President Zachary Taylor said, however, that there were enough people there and California was extremely valuable. “No matter” he said as he urged Californians to skip the customary territorial phase and apply directly for statehood. The “49ers” held a constitutional convention during September and October 1849 and sent the document to Congress for approval. California applied for admission to the Union as a free state and was eventually added as a state under the Compromise of 1850. Pro-slavery circles concerned about the annexation of California were appeased by the addition of two federal territories (one in present day Utah and Nevada; one in present day New Mexico and Arizona) both potential slave states in the future. Daniel Webster “The Constitution and the Union” speech (1850) Henry Clay speech on preserving the Union (1850) Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 The Kansas-Nebraska Act was part of the scheme devised by Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois (Chairman of the Senate Committee on the Territories) in his attempt to win a central route for America’s first transcontinental railroad. Such a plan/route would make Chicago Douglas’s home state) the eastern terminus of the line. In order to make a central route to California feasible, Douglas had to organize federal territories in the unorganized prairies of the mid-west (only in official territories could the federal government provide the law, order, and security such a great construction project would require). Southern congressmen were not likely to support a plan to organize territories so far north, particularly since, under the Missouri Compromise, slavery would be forbidden in those territories since they were north of 36°30’. Such a development would have tipped representation in the Senate in the North’s favor jeopardizing southern interests such as slavery. Obtaining a central route was more important to Douglas than was keeping slavery out of the territories. Douglas therefore introduced the Kansas Nebraska Act in 1854. If passed, the Kansas-Nebraska Act would have repealed (that is erased) the Missouri Compromise line, meaning that slavery would no longer be forbidden north of 36°30’. Instead, the choice of whether to legalize slavery would be left to the voters who settled the newly organized Kansas and Nebraska territories. In other words, popular sovereignty (the will of the people) would resolve the question of slavery democratically in the territories. With southern support, the Kansas Nebraska Act became law. Southerners only supported this bill, however, because of the possibility it created to extend slavery into territory it was previously banned from (they still supported Jefferson Davis’s sponsorship of the Gadsden Purchase and his proposed southern route). Meanwhile, a number of northern anti-slavery politicians detested the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a violation of the “sacred pledge” of the Missouri Compromise. As a result, these politicians broke from the party and formed the Republican Party. Despite northern positions on slavery, most northerners still supported Douglas’s proposal of a central route. May 22, 1856 The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner URL: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Caning_of_Senator_Charles_Sumner.htm Lithograph of Preston Brooks’ 1856 attack on Sumner; the artist depicts the faceless assailant bludgeoning the learned martyr. “Sir, disguise the fact as you will, there is an enmity between the northern and southern people that is deep and enduring, and you never can eradicate it - never! Look at the spectacle exhibited on this floor. How is it? There are the Republican northern Senators upon that side. Here are the southern Senators on this side. How much social intercourse is there between us? You sit upon your side, silent and gloomy; we sit upon ours with knit brows and portentous scowls. Yesterday, I observed that there was not a solitary man on that side of the Chamber came over here even to extend the civilities and courtesies of life; nor did any of us go over there. Here are two hostile bodies on this floor; and it is but a type of the feeling that exists between the two sections. We are enemies as much as if we were hostile States. I believe that the northern people hate the South worse than ever the English people hated France; and I can tell my brethren over there that there is no love lost upon the part of the South.” Utterance of Democratic Senator, Alfred Iverson, during the Second Session of the Thirty-sixth Congress on December 5, 1860 Comments were made on the eve of the “secession winter” and war and they revealed the extent of sectional animosity that existed at that time. nationalism (consolidation) versus sectionalism (“states rights”) • Ultimately, the issues involving interposition, nullification, and secession would be settled outside the political arena on the military battlefield. y7h Different views of the Civil War Northern view: • “Civil War” • “The War of the Rebellion” *Northerners/Unionists/ Abolitionists viewed the Confederates as the guilty party or the aggressors/ perpetrators responsible for starting the war (i.e. their actions threatened the perpetuation of the Union). Southern view: • “The War of Northern Aggression” • “The War Between the States” • “The War of Southern Independence” *Confederates/Southerners assigned blame to the North— southerners were defending their rights as individuals and/or states. Different views of the conflict contd. Northern view: • • • • From the northern perspective, war ensued from a conspiracy of a small group of slaveholders and secessionists. These conspirators were bent on either ruling the nation (e.g. forcing the nation to protect slavery in the States and Western territories) or destroy it in the attempt. Northerners were merely defending the Union and the U.S. Constitution against unprovoked southern aggression and agitation. According to this perspective, secession was tantamount to both treason and rebellion. Southern view: • • • • • Alleged that “Black Republicans,” abolitionists, and “other northern extremists” were “determined to provoke southern slave insurrections and encourage slaves to escape.” Claimed to be victims of northern and Republican aggression—that is, their attempts enhance their power at the expense of the South and its institutions. Chastised the North for its exploitation of them both politically and economically through unconstitutional means in the cause of assuming national control. Southerners, for their part, were merely defending their inherited right of selfgovernment. Identified slavery as only a pretext, occasion, or excuse propagated by the North to wage war and crush southern opposition to northern tyranny. Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, a former U.S. Senator (1855-1873) and Vice President under Ulysses S. Grant “[the] slave power….[has] organized treasonable conspiracies, raised the standard of revolution, and plunged the nation into a bloody contest for the preservation of its threatened life.” Edward Pollard was vocal secessionist who became wartime editor of the Richmond Examiner newspaper. • Pollard defended southern actions for attempting to preserve (not destroy) existing institutions. • The act of secession was intended as a defense against northern aggression; it provided the surest defense, security, and protection of southern property and institutions against “northern fanaticism.”