* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Economics for Educators, Revised

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

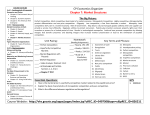

Economics for Educators Lesson 7 and 5E Model Revised Edition Robert F. Hodgin, Ph.D. Texas Council on Economic Education ii Economics for Educators, Revised Copyright © 2012 Texas Council on Economic Education All Rights Reserved Texas Council on Economic Education 35 Economics for Educators, Revised Lesson 7: Competition, Market Power and Economic Efficiency Market Power and the Structure of Industry The economics of industry is about market power—the power to set product price, gain market share and improve profits. The study of economic welfare, where the social goal is to efficiently solve the economic problem for all citizens—prefers competitive markets above all others. For it is only purely competitive producers, due to their individual powerlessness to affect price, that offer society the most output at no more than the opportunity cost to produce it as firms pursue profit maximization. In stark contrast, monopolistic markets permit the ruling firm to restrict output and raise the price for their production as they search for the price, above opportunity cost, that maximizes their profit. Between the polar market structures of competition and monopoly lie two others: monopolistic competition—a blend of competitive extremes; and oligopoly—a peculiarly postured industry where a few large firms strategically spar for market share in game-like fashion. Competition’s Efficiency Promise Perfect competition is a fiction, though a highly useful one. It serves as an ideal against which to compare diversions from the economically desirable position of maximum efficiency and output. Much of competition’s value rests in its ability to show just how far from the ideal other market solutions may lie. Many public policies also can be judged against their progress toward reaching selected competitive criteria. Since perfect competition resides only in the economist’s mind, what does it look like and what is its logic? The industry characteristics that create this idealized market structure include the following: very many buyers and sellers; identical products; costless entry into and exit from the market; perfect market information and costless market mobility. These characteristics combine to form a market where no one actor—buyer or seller—or small group of actors can influence market equilibrium results. Competitors have no price-setting power. The market for selling and buying corn comes close to these requirements. Fast, faceless and efficient exchanges work through market demand and supply to achieve an equilibrium price that clears the market. So powerless is each competitive seller to affect market price that they can only accept the established equilibrium price as the per unit revenue they will receive for selling their product. Effectively, their demand curve is horizontal (completely elastic). The result is that the only decision a producer needs to make for a current cycle is to choose the level of production. Texas Council on Economic Education 36 Economics for Educators, Revised Inspect the chart above, and notice that equilibrium market price equals $20—any seller’s revenue per unit. Further note that opportunity cost rises as production increases. In this situation, a rational seller will gladly produce up to 4 units per period for sale. Why? Each unit of output up to the 4th unit sells at a price above its opportunity cost and adds to profit. To produce beyond that point, say the 5th unit is not rational because its cost ($25) is greater than the market equilibrium price received ($20) and lowers profit. So the optimum output rate, the one that will generate the most profit, if profits are being made, is 4 units. How could it be that the seller might not be making a profit if each unit sells for more than its opportunity cost? In the chart above, the amount of overhead cost was not provided. Once known, short run profit determination can be made. Profit maximizing rule—operating at the level of output where market price equals marginal cost will either maximize profits or minimize losses, if they are incurred. The competitor’s rule is to produce at the level of output where price equals marginal cost, the opportunity cost of production. By doing so, any profits will be maximized or any losses will be minimized. This extreme competitive pressure guarantees private goods brought to market will sell for a price equal to marginal cost—the opportunity cost. Further, there will be more product available at that price than would be available through any other market structure. These results reflect competition’s efficiency promise for private goods in the short run. In the long run the efficient firms best able to sustain profits by controlling cost can survive and grow. Texas Council on Economic Education 37 Economics for Educators, Revised Monopoly’s Efficiency Failure At the opposite end of the competitive spectrum lies monopoly, a market possessing only one seller but many buyers. Monopoly represents one of four cases of efficiency failure in economic analysis, where failure means an inefficient allocation of goods in comparison to competition. A monopoly may achieve its market power position by taking advantage of large economies of scale, growing so large that no other firms can effectively compete on cost. A monopoly also may be granted by regulatory authority, as with a patent, legally prohibiting other rivals. Finally, a monopolist can be the sole owner of a natural resource, like a water company. No matter the genesis of a monopoly, economists detest its effects on economic welfare. Because the monopolist faces the downward sloping demand for the entire market, two important observations can be made. One, there are no close substitutes available to the monopolist’s product, so the firm has significant price setting power. Two, market entry barriers are prohibitively high. The only way for another firm to enter the market is to slay the existing monopolist. A monopolist incurs opportunity costs to produce its output, just like a competitive firm does, though it is under less pressure to control those costs. It also has the same business objective as a competitive firm: maximize profits. To achieve that objective, the monopolist does something the competitor cannot—change price. The monopolist also knows that additional sales can only occur through a price drop. So what makes monopoly behavior loathsome in the economist’s mind? Compared to competition, a monopolist’s price-setting power enables it to search out the price that maximizes profits. That price is higher than marginal cost and achieved due to a restriction in output. How does this happen? Like a competitor, a monopolist will produce additional units of output only as long as the additional revenue exceeds the additional cost of each unit. The culprit is the monopolist’s down-sloping demand curve, allowing it price searching power to maximize profits as buyers have no or very few close substitutes. In the lower (and inelastic) half of a monopolist’s demand curve, price increases generate rising additional revenue so total revenue also rises. Inevitably, the monopolist’s profit maximizing price search stops short of the output level a competitor firm would attain. Finally, the quantity demanded at that output allows the firm to charge a price above the opportunity cost of production. In response, and in fairness, the monopolist’s management would claim that they are pursuing the same rational economic goal as competitor firms, acting on behalf of their stockholders. Their statement would be true but at the cost of reduced economic welfare— fewer units available for purchase sold at a price above opportunity cost. This reality is one of the key justifications for government regulation of some monopolized markets. Texas Council on Economic Education 38 Economics for Educators, Revised When a Few Firms Dominate the Market Moving away from the monopoly end of the competitive continuum, we find a structure where several firms compete for many buyers. US industries where competition is highly concentrated in the hands of relatively few firms include airlines, steel, petroleum refining, and automobiles. These rivalry-intense industries, dominated by a few large firms, employ competitive strategies directly related to the similarity of their products. Entering and exiting the industry is sufficiently expensive that a firm’s threat to enter or leave the industry must be credible. Rival firm competition may manifest in the form of price, output or product features. Advertising may be aggressively used as a common strategic tool to gain market share, especially where similar competing products or services show observable differences. Rival firms can also compete on the basis of price or output in a context not unlike a game. Airline Oligopoly Game Matrix Northwest Airlines Price high Price low Southwest Airlines Price high Price low Profit / Profit Loss / High Profit High Profit / Loss Loss / Loss In the strategic pricing table above, two airlines each face two route-pricing options that determine possible profit payoffs from independent choices made by each firm. The payoffs for each set of choices are shown in the respective cells as [Northwest/Southwest]. Suppose each firm must decide if and when to change their own pricing structure with the end of the travel season near. What choice should each airline make and why? Notice how both airlines could benefit by maintaining their current high prices. But the reward for low pricing to gain market share, if the rival does not also price low, is very appealing to airlines operating on thin profit margins. Should both airlines choose to price low, they each suffer a loss by splitting the market with lower fares. This is an example of a famous economic game know as the “prisoner’s dilemma” where actions that might benefit each separately injure both if undertaken jointly. Southwest must consider its best response to either action by Northwest. If Northwest prices high, Southwest earns more by pricing low. If Northwest prices low, Southwest still earns more by pricing low. Likewise, no matter what Southwest does, Northwest also is better off choosing to price low. The result of this game is that both airlines, playing strategically, will price low…unless they can successfully collude to keep prices high with neither cheating to earn more profit in the short run. This type of collusion is a violation of federal law, with serious penalties for the colluding if firms. Texas Council on Economic Education 39 Economics for Educators, Revised Games like this are common among the rivals in oligopoly industries. Often, there can be tacit collusion where the largest rival will act the part of a price leader and move first to change price, with the expectation that others will quickly follow. Airline route games of this sort have revealed a more sinister side in recent years as rivals have sometimes refused, between holiday peak pricing periods, to follow their price leader, to the detriment of the leader’s profit. Monopolistic Competition Moving farther away from the monopolistic and closer to the pure competition end of the competitive continuum, we find industries blending elements of both competition and monopoly. Example industries include dry cereal, men’s and women’s clothing, hotels and many other retail products. Entering or leaving this industry is relatively less expensive than for oligopoly industries. The relatively large number of firms in monopolistically competitive industries still allows some degree of price setting power—their individual demand curve slopes down to the right. Rival firms engage in stiff competition based on product feature similarity, location, advertising affects and other strategic economic dimensions. For these firms, significant resources are applied to the marketing function. Marketing includes all activities between product production and customer purchase as a legitimate cost of product positioning. Components of marketing as strategic tools 9 Advertising Distribution activities 9 Transportation and storage Product planning 9 Market research Customer service 9 Financing Product design Characteristic Price setting power Product similarity Price to opportunity cost Excess capacity Advertising Market entry cost Information access Pure Competition None Identical Equal & “Ideal” None None Zero Total Texas Council on Economic Education Monopolistic Competition Little Similar/Identical Price above Some Much Modest Modest Oligopoly Some Similar/ Identical Price above Some Much High Limited Monopoly Much N/A Price far above Much Little Great Limited 40 Economics for Educators, Revised Monopolistically competitive firms’ product demand curves are interdependent due to the closeness of rival product features to their own. A price decrease for one firm’s product can lower the demand for a close rival as the rival product’s customers opt out in favor of the now less expensive and not-that-different substitute, for example frozen turkey dinners instead of frozen chicken dinners. A similar demand response is possible from successful advertising campaigns. If one firm aggressively advertises customerimportant features, buyers may leave the rival product’s market to join that of the newly perceived “better” product. Television commercials often mention the name of the closest rival and compare selected features. The economic objective of all advertising is to increase demand for the one product—a rightward shift—and to make the demand inelastic—less responsive to a rival producer’s campaign in the market place. Texas Council on Economic Education 41 Economics for Educators, Revised In Sum 9 Economics strongly favors competitive markets because forces work to bring equilibrium price down to opportunity cost and to provide more output than any other market structure. Competitive market characteristics include: o Very many buyers and sellers o Identical goods o No market entry or exit costs o Costless market information and mobility 9 Competitive markets efficiently achieve an equilibrium price and quantity that clears the market. o They are “powerless price takers” and must accept the market’s price as their own as they seek to maximize profits. o They produce output up to the point where the market price just equals the opportunity cost of the last unit produced. 9 Monopolies—single sellers—face a downward sloping demand curve for the entire market comprised of many buyers. o To sell more the monopolist must lower price. o Monopolies are economically inefficient since: Their market pricing power lets them search for the price that maximizes profits, and At the monopoly’s profit maximizing price: x Output is lower than for a competitive market x Price lies above the opportunity cost for the output Because output is inefficiently allocated monopolies represent a form of market failure. 9 Oligopoly industries contain many buyers and several rival firms with interdependent product demand where strategic pricing and production games are common. o Large market entry and exit costs o Competition can be on the basis of price or output depending on the nature of the good. o Advertising is common when rivals produce similar goods with differing features. 9 Monopolistic competition represents an industry with many sellers and very many buyers. o Market entry and exit costs are low o Product differentiation is used to gain market share o Advertising is a strategic tool designed to: Increase product demand—shift rightward Decrease product demand elasticity 9 All less-than-competitive industry structures are relatively inefficient compared to pure competition and prevent society from receiving the full value of additional production and lower product price. Texas Council on Economic Education 1801 Allen Parkway * Houston, TX 77019 * (713)655-1650 * Fax: (713)655-1655 Email: [email protected] * www.economicstexas.org The students should begin to find that the prices are the same for eggs, the prices are similar for the same type of clothing, similar cars have some variance in prices, and while home water prices may be similar, producers have great control over pricing. Have the students look at ads for several sellers (online & other media) to determine the differences or similarities in price for eggs, clothes, cars, water for the home. How much control do the sellers have in setting prices? Explore (Students may only be familiar with retail stores where prices are set – but remind them of “sales which are a reaction to lack of demand”; also an almost true competitive market does exist at “famers’ markets, garage/flea sales, etc. where the producers is able to interact with the consumers) The answers will vary for these questions and this is acceptable. Explain that they may be surprised as they truly explore competition that the market forces may actually be different from what their expectations. What do you think a truly competitive market will look like? How much control do you and members of your household have over the price you pay for: eggs, clothes, cars, water for your home. Engage Lesson 7: Competition, Market Power and Economic Efficiency, page 35 Page | 23 1801 Allen Parkway * Houston, TX 77019 * (713)655-1650 * Fax: (713)655-1655 Email: [email protected] * www.economicstexas.org The examples will vary but the rationale and reasons need to be accurate as to which type of competition each will be. Using the chart on page 39, they will need to accurately demonstrate understanding of how their products will fit with the characteristics. Have the students work in groups of four. Each group will create 4 products of the future – one for each type of competition. They need to illustrate their products and explain why and how it fits with the characteristics of that type of competition. Extend Water piped into the home has a monopoly with the producer having total control of cost (usually with government oversight). These are products that would be inefficient if there was more than one producer. Cars are an example of an oligopoly. The high cost of production means that few can afford to manufacture. Thus, the producer has greater control over the pricing. Clothing is considered monopolistic competition. While there are many styles and prices for clothing, there is such strong competition for each type of clothing style that producers have little control over price. They must set competitive prices if they want to sell their products. Eggs represent a purely competitive market because the products are basically the same. While there may be organic vs. brown eggs vs. regular eggs, there are so many produced that the market forces leave little control over price by the producer. What does competition really mean? How much control do producers of eggs, clothes, cars and water really have over prices? Why? How much choice do buyers really have? Explain Page | 24 None Identical Equal & “Ideal” None None Zero Total Characteristic Price setting power Product similarity Price to opportunity cost Excess capacity Advertising Market entry cost Information access Little Similar/Identical Price above Some Much Modest Modest Monopolistic Competition Some Similar/ Identical Price above Some Much High Limited Oligopoly Monopoly Page | 25 Much N/A Price far above Much Little Great Limited 1801 Allen Parkway * Houston, TX 77019 * (713)655-1650 * Fax: (713)655-1655 Email: [email protected] * www.economicstexas.org Pure Competition If there is too little time to have every group explain in front of the class, model the presentations with two to three groups that you feel will be accurate and then have the class discuss whether they agree or disagree. In addition, have each student write responses to these groups. Then, collect the group work and the responses to the presentations for a grade. The students will evaluate the presentations of the other students. At the conclusion of each presentation, each student will write a sentence for each product explaining whether they agree with the types of competition or not. They will need to give a reason. If they disagree, they need to say under what category they would have placed it and why. Evaluate The Texas Council on Economic Education (TCEE) thanks the Council for Economic Education and the Department of Education Office of Innovation and Improvement for awarding the Replication of Best Practices Program grant that allowed Economics for Educators, Revised Edition to be written and published. The Texas Council on Economic Education also thanks six of its major partners whose support allows TCEE to provide the staff development that utilizes content and skills provided in Economics for Educators. Helping young people learn to think & make better economic & financial choices in a global economy. economicstexas.org 1801 Allen Parkway Houston, Texas 77019 Telephone 713-655-1650 Fax 713-655-1655 Email: [email protected]