* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Remittance Facts

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

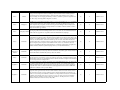

Topic

Country

Immigration

United States

Immigration

United States

Immigration

United States

Immigration

United States

Volume

Various

Volume

Various

Volume

United States

Prices

Worldwide

Immigration

Worldwide

Immigration

Immigration

Immigration

Fact

Immigrants are a growing part of the labor force. In 2010 there were 23.1 million foreign-born persons in

the civilian labor force, making up 16.4% of the total. As the foreign-born population has grown as a share

of the total population, they have grown disproportionately as a share of the labor force. By 2010

immigrants were 16% of the labor force, but only 13% of the total population.

In the second half of the 2000s, immigration slowed and the share of labor force growth attributable to

immigrants dipped to 42% of the total.

Nearly one-in-three immigrants lack a diploma. Immigrants are nearly as likely as natives to have a college

degree but much more likely to lack a high school diploma.

Immigrants are over-represented in certain industries: Immigrants represent 15.8% of the civilian employed

population overall, but are over-represented in high- and low-skill industries.

In 2010, the top recipeint countries of recorded remittances were India, China, Mexico, the Philippines,

and France. As a share of GDP, however, smaller countries such as Tajikistan (35%), Tonga (28%),

Lesotho (25%), Moldova (31%), and Nepal (23%) were the largest recipients in 2009.

Worldwide

Volume

Worldwide

Immigration

Mexico-U.S.

Page Number

Date Accessed

(3)

March 22, 2012

(3)

March 22, 2012

(3)

March 22, 2012

(3)

March 22, 2012

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

Top 10 remittance senders in 2009 (billions): the United States ($48.3 bn), Saudi Arabia ($26.0 bn),

Switzerland ($19.6 bn), Russian Federation ($18.6 bn), Germany ($15.9 bn), Italy ($13.0 bn), Spain

($12.6 bn), Luxembourg ($10.6 bn), Kuwait ($9.9 bn), Netherlands ($8.1 bn)

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

High-income countries are the main source of remittances. The United States is by far the largest, with $48

billion in recorded outward flows in 2009. Saudi Arabia ranks as the second largest, followed by

Switzerland and Russia.

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

In the third quarter of 2011, sending $200 abroad, including fees and exchange-rate margins, cost $18.60

on average, an increase of almost 5% on a year earlier. India and China are the largest remittance-receiving

countries. Depending on the migrant workers' country of residence, the cost of sending money home varies

significantly. Japan is the most expensive from which to send money to India or China, followed by France.

Sending money from America and Britain however is much cheaper.

More than 215 million people, or 3 percent of the world population, live outside their countries of birth.

The top migrant destination country is the United States, followed by the Russian Federation, Germany,

Worldwide

Saudi Arabia, and Canada.

The top immigration countries, relative to population are Qatar (87%), Monaco (72%), the United Arab

Worldwide

Emirates (70%), Kuwait (69%), and Andorra (64%)

South-South migration (migration between developing countries) is significantly larger than from the South

Developing Countries to high-income OECD countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (73%) and Europe and Central Asia (61%).

Immigration

Source

Refugees and asylum seekers made up 16.3 million, or 8% of international migrants in 2010. The share of

refugees in the migrant population was 14.6% in low-income countries compared with 2.1% in highincome OECD countries.

In 2011, $483 billion in remittances were sent worldwide. The true size, including unrecorded flows

through formal and informal channels, is believed to be significantly larger.

According to available official data, Mexico–United States is the largest migration corridor in the world,

accounting for 11.6 million migrants in 2010.

(6)

March 22, 2012

(1)

ix

March 22, 2012

(1)

ix

March 22, 2012

(1)

ix

March 22, 2012

(1)

ix, x

March 22, 2012

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

(1)

x

March 22, 2012

Topic

Volume

Volume

Volume

Volume

Country

Fact

Remittance flows to developing countries proved to be resilient during the global financial crisis - they fell

only 5.5% in 2009 and registered a quick recovery in 2010. By contrast, there was a decline of 40% in FDI

Developing Countries flows and a 46% decline in private debt and equity flows in 2009. Remittances are a small part of migrants'

incomes, and migrants continue to send remittances when affected by income shocks.

Date Accessed

(1)

x, 17

March 22, 2012

Globally, the flow of personal transfers, and certain compensation, goods, services, and assets from

migrants to their native countries is significantly larger than the flow of official development aid and almost

as large as foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to developing countries.

(1)

x, xvi-xvii

March 22, 2012

Worldwide

Workers' remittances are current private transfers from migrant workers who are considered residents of the

host country to recipients in the workers' country of origin. If the migrants live in the host country for one

year or longer, they are considered residents, regardless of their immigration status. If the migrants have

lived in the host country for less than one year, their entire income in the host country is classified as

compensation of employees.

(1)

xiv

March 22, 2012

(2)

1

March 22, 2012

(2)

1

March 22, 2012

(2)

1

March 22, 2012

(2)

11

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

(2)

12

March 22, 2012

Officially recorded remittance flows to developing countries are estimated to have reached $351 billion in

2011, an 8% increase over $325 billion in 2010. The growth of remittance flows to developing countries is

Developing Countries expected to continue at a rate of 7-8 percent annually and to reach $441 billion by 2014.

Worldwide

Prices

Worldwide

Volume

Page Number

Worldwide

Volume

Volume

Source

Europe

Worldwide remittance flows, including those to high-income countries, are expected to exceed $590 billion

by 2014.

Remittance costs have fallen steadily from 8.8% in 2008 to 7.3% in the third quarter of 2011. However,

remittance costs continue to remain high, especially in Africa and in small nations where remittances

provide a life line to the poor.

Quarterly remittance outflows data up until the second half of 2011 suggests that the growth of remittance

outflows from Western European countries have increased from levels seen at the height of the global

financial crisis in 2008-09, but there has not been a sustained recovery because of the weak economic and

employment situation in these countries. Outward flows from UK, Italy and Spain are still well below the

levels prior to the crisis, while outflows from France have been declining consistently since the last quarter

of 2008.

Despite the crises in North Africa (the "Arab Spring") and the difficult economic situation in Europe,

Sub-Saharan Africa remittance flows to Sub-Saharan Africa are estimated to have increased by 7.4% in 2011.

Volume

Kenya

Volume

Ethiopia

Immigration

Niger

Immigration

Chad

Volume

Egypt

Volume

Tunisia

Remittances from Kenyan migrants grew to $644 million in the first nine months of 2011. Inflows surged

by 45% on a year-on-year basis in part because the weak Kenyan shilling made it more attractive to invest

in local currency assets.

Remittance flows to Ethiopia are reported to have increased to more than $1.5 billion in the 2010-11 fiscal

year.

According to the Government of Niger, some 200,000 Nigeriens have returned to the country after the

crisis began in Libya

Chad has also seen many migrants in Libya return home after the crisis, causing a burden on scarce

resources in the country as well as loss of future remittances.

Hundreds of thousands of Egyptians have returned home since the (Libya) crisis began, causing a

deceleration in the growth of remittances to the country in 2011.

Many Tunisians have returned home from Libya, which has adversely effected remittance flows

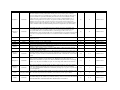

Topic

Country

Prices

Worldwide

Prices

Prices

Worldwide

Fact

The G8 and the G20 countries have agreed to the objective of reducing global average remittance costs by

5 percentage points in 5 years ("5 by 5" objective). A 5 percentage point reduction of the global average

cost of remittances' flows is believed to translate into an additional US$ 15 billion annually for recipient

populations.

The World Bank's Remittances Prices Worldwide database shows that the simple average remittance cost at

the global level declined between 2008 and the first quarter of 2010, but then appears to have increased in

subsequent quarters. The average remittance cost, weighted by bilateral remittance flows, however, has

registered a consistently delining trend. Average remittance costs fell from 8.8 percent in 2008 to 7.3

percent in the third quarter of 2011. There is evidence that costs have been falling in high volume

remittance corridors, such as from the US to Mexico, UK to India and Bangladesh, and France to North

Africa.

Although the simple average cost of sending remittances to Sub-Saharan Africa is the highest among the six

developing regions, the weighted average costs for the Middle East and North Afria and East Asia and

Pacific are higher. This is because these regions have several large remittance corridors with relatively high

Developing Countries costs. For example, it is more expensive to send remittances from France to Morocco or from US to China

than it is from UK or US to Nigeria. However, Sub-Saharan Africa, excluding Nigeria, has many smaller

remittance corridors with significantly higher costs.

Volume

Latin America

Volume

Worldwide

Volume

Mexico

Employment

Mexico-U.S.

Immigration

Latin America

Volume

Latin America

Immigration

United States

Immigration

Mexico-U.S.

Remittance flows to Latin America and the Carribbean are estimated to have increased by 7% in 2011 after

remaining almost flat the previous year.

In line with the World Bank's latest outlook for the global economy, remittance flows to developing

countries are expected to grow by 7.3% in 2012, 7.9% in 2013, and 8.4% in 2014. They are expected to

reach $441 billion by 2014. These forecasted rates of growth are considerably lower than those seen prior

to the global financial crisis, when the annual increases in remittances to developing countries averaged

20% during 2003-2008.

Remittances to Mexico surged by 11% in 2011Q3, in part because of the depreciation of the Mexican Peso

relative to the US dollar.

Since the start of the financial crisis in 2008, the employment of migrants in the US has declined less (3.7%) than natives (-4.1%).

The US hosts some three-quarters of all emigrants from countries in the Latin American and Caribbean

region.

Remittances to Latin America have also been affected by the global financial crisis and hgh unemployment

in Spain. Spain hosts about one-tenth of all Latin American migrants.

Arrests by the U.S. Border Patrol along the southwestern frontier, a common gauge of how many people

try to cross without papers, tumbled to 304,755 during the 11 months ended in August 2011, extending a

steady drop since a peak of 1.6 million in 2000.

About 12.5 million Mexican immigrants live in the United States, slightly more than half without papers,

according to the Pew Hispanic Center.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(2)

13

March 22, 2012

(2)

13

March 22, 2012

(2)

13

March 22, 2012

(2)

2

March 22, 2012

(2)

2

March 22, 2012

(2)

4

March 22, 2012

(2)

4

March 22, 2012

(2)

4

March 22, 2012

(2)

5

March 22, 2012

(2)

5

March 22, 2012

(2)

5

March 22, 2012

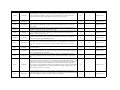

Topic

Country

Volume

India

Exchange Rates

Mexico-U.S.

Fact

Although oil driven economic activities have provided a chusion for remittances to Asian countries,

remittance flows to India (the largest recipient among developing countries) appear to have been relatively

more affected by the weak employment in the US and by the debt crisis in Europe. Quarterly data show

that private current transfers - composed mostly of migrant remittances - increased by 33% in 2010Q1 in a

recovery to the pre-crisis levels of early 2008. However, the growth of remittance inflows has been anemic

in the subsequent period, averaging just 4% since 2010Q2. Remittance flows, especially from the GCC, are

reported to have surged in the second half of 2011 because of a weakening rupee, which may have

prevented remittances from slowing even further in the second half of 2011.

Currency depreciation in many recipient countries is increasing the migrants' incentive to remit: The

Mexican Peso depreciated by nearly 14% between July and November 2011, while remittances to Mexico

increased by 11% in the third quarter on a year on year basis more than doubling from a five percent

average growth in the first half of the year. While part of this increase is because of the economic recovery

in the US, this is also related to the increased purchasing power of remittances.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(2)

7

March 22, 2012

(2)

8

March 22, 2012

(2)

8

March 22, 2012

Immigration

GCC

Saudi Arabia has nearly six migrant workers for each Saudi native in the private sector labor force. The

Saudi private sector will continue to predominantly rely on foreign labor in the forseeable future, and the

opportunity of substitution between Saudi job seekers and migrant workers in the production process

continues to be heavily constrained. Indigenization eforts will displace only a small fraction of foreign

workers, if at all.

Volume

Spain

Despite high levels of unemployment of migrants in Spain, remittance outflows grew by about 15% in the

first half of 2011, as migrants cut into their savings (and even consumption) to be able to send remittances,

and also to prepare for a potential return if the crisis deepened further

(2)

9

March 22, 2012

Spain

Since the financial crisis, Spain has introduced new policies that have made burdensome the process of

hiring foreign workers by employers, in particular a new minimum salary requirement and discontinuation

of an expedited immigration processing option for large businesses. Spain has also seen migrants return to

their home countries since the end of the construction boom in 2007. These include migrants from Ecuador,

Colombia, Argentina and Peru as well as low-skilled migrants from North Africa who have moved on to

other European countries.

(2)

9

March 22, 2012

(2)

9

March 22, 2012

(4)

1

March 22, 2012

Immigration

Immigration

UK

Volume

Worldwide

The UK has imposed tougher admission criteria for non-EU migrants, with the objective of reducing annual

immigration from the hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands. Employers seeking to hire non-EU

migrants are now subject to an annual quota and the "shortage occupation list" has been shrunk. Policies

have also been introduced that have made it difficult for foreign students to come to the UK as students. The

UK Home Office is also considering legislation that would prevent foreign workers earning below a certain

threshold to bring their families to the UK. However, employers and universities warn that such restrictions

may reduce future productivity and growth.

Remittances fell only 5.4% in 2009 compared to a 36 percent decline in foreign direct investment (FDI)

between 2008 and 2009 and a 73 percent decline in private debt and portfolio equity flows from their peak

in 2007.

Topic

Country

Volume

Worldwide

Fact

In line with a recovering but still fragile global economy, remittance flows to developing countries are

expected to increase in 2011-13, but at lower and more sustainable rates compared to the period prior to

the global financial crisis. World output is expected to grow at a slightly slower pace of about 4.5 percent

annually in 2011-12 compared to average growth of 5.0 percent during 2004-07 in the period before the

financial crisis. The advanced economies are forecast to grow at less than 3 percent annually during 201112.

The reduction in local currency value of remittances implies hardship for recipients, and increased pressure

on migrants to send more to maintain the purchasing power of their remittances. Among the largest ten

recipients of remittances in developing regions, four experienced a nominal appreciation of their currencies

against the US dollar. For instance, while remittances to India, the largest recipient in 2010, are estimated

Exchange Rates Developing Countries to have grown by 7.4 percent in US dollar terms, it experienced an almost flat growth of 1.5 percent in

local currency terms. Since India also had a relatively high rate of inflation in this period, the purchasing

power of remittances actually decreased by 10.4 percent.

Volume

Volume

United States

United States

Immigration

Australia

Immigration

Australia

Volume

Eastern Europe

Remittance flows to Latin America started recovering in 2011 with an incipient economic and labor market

recovery in the US and sectoral shifts in migrant employment. The pace of decline in flows to Latin

America slowed in the second half of 2010, and flows started growing again in the first quarter of 2011.

For Latin American countries with available remittance data for the first quarter of 2011 – Mexico,

Colombia, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua which together account for 70 percent of

remittance flows to the Latin America & Caribbean region – remittance inflows grew at 7.1% in the first

quarter of 2011 on a year on year basis. This rebound is remarkable particularly because remittances to the

region fell sharply by 12% in 2009 and remained close to flat in 2010.

The increase in remittance flows from the United States since the global financial crisis are mainly

attributable to a recovery in migrant employment in the United States and sectoral and geographical shifts

away from a still depressed construction sector toward growing manufacturing and services sectors.

Housing construction in the US has traditionally been a large employer of Hispanic migrants but continues

to remain depressed. The shift in migrant employment away from construction towards other sectors has

resulted in a decoupling of a relatively close correlation between US housing starts and remittance flows to

Mexico.

Resource-rich countries, such as Australia, that are benefiting from high global commodity prices are

planning to increase their intake of migrant workers. Australia is expected to have a shortage of 2.4 million

skilled and semi-skilled workers by 2015, with the mining sector reporting $250 billion in planned projects

experiencing a severe shortage of skilled workers. To fill skills gaps in the resources sector, Australia has

introduced Enterprise Migration Agreements (EMAs) available to large Australian companies with

minimum capital expenditures of 2 billion Australian dollars (US$2.1 billion), with no caps on the number

of workers brought in under these agreements.

Australia tightened restrictions on certain migration in 2011, reducing the number of occupations in its list

of General Skilled Migration program from 298 to 181.

Remittance inflows to Eastern European countries such as Poland (a major sender of migrants to the UK),

Romania and Bosnia & Herzegovina remained in negative territory in 2010.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(4)

1

March 22, 2012

(4)

10

March 22, 2012

(4)

3

March 22, 2012

(4)

3

March 22, 2012

(4)

5

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

Topic

Country

Immigration

UK

Immigration

Australia

Exchange Rates

Volume

Volume

Monitoring

Transaction

Method

Worldwide

Fact

There has been resistance among employers such as business associations and medical and academic

institutions facing shortages of workers and students. After implementing immigration caps in early 2010,

the UK responded to resistance from employers by adding exceptions to its cap to high skilled migrants

earning more than £150,000 per year.

With increasing perception of having unwelcoming labor markets, Australia saw a plunge in the number of

international students in its universities, and has commissioned a review of its student visa program.

Remittances fell in purchasing power terms in 2010 because of currency appreciation and inflation in

developing countries. The currencies of several large remittance-recipient countries have appreciated

relative to US dollar. Between March 2009 and March 2011, the currency of Mexico appreciated by 22

percent relative to the US dollar, India’s by 14 percent, and the Philippines’ by 11 percent . This

appreciation, combined with higher rates of inflation in developing countries, implies that migrants have to

send more in dollar terms to simply maintain the purchasing power of recipients. During the same period,

the Russian Ruble appreciated by 22 percent and the Euro by 8 percent implying larger flows to recipient

countries in US dollar terms than in local currency terms. This has cushioned to some extent remittance

flows to countries in Central Asia from Russia, and Africa and other regions that receive remittances from

countries in the Euro area.

Remittances flows to developing countries recovered to the pre-crisis level of $325 billion in 2010, but

have failed to keep up with rising prices and the appreciation of currencies of several large recipient

Developing Countries countries relative to the US dollar. While remittances grew 5.6 percent in US dollar terms in 2010, they

grew by a smaller 3.9 percent after accounting for exchange rate changes, and fell by 2.7 percent after

adjusting for inflation

Latin America

Worldwide

Worldwide

The largest decline in remittances adjusted for inflation in 2010 was for countries in the Latin America and

the Caribbean region, which experienced both sustained appreciation of their currencies with respect to the

US dollar and domestic inflation. While remittance flows to the Latin America region remained almost flat

in nominal US dollar terms, they declined by 2.9 percent after accounting for exchange rate changes, and

fell by 6.9 percent after adjusting for inflation. A similar decline the purchasing power of remittances was

observed for South Asian countries where high inflation (especially in India) converted an 8.2 percent

increase in US dollar terms to a decline of 6.3 percent in purchasing power terms.

Central banks are beginning to pay attention to new technologies and alternative channels when recording

remittance transactions. Transactions recorded as migrant remittance inflows are typically those through

banks, money transfer operators, and post offices. However, some central banks are beginning to record

transactions through new technologies such as debit and prepaid cards used at retail stores (Belarus, Cyprus,

El Salvador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Morocco, Nicaragua, Polond, and Uganda), transfers through mobile

phone (Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines), and even purchases of homes by migrants for beneficiaries

(Belarus, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Cyprus, Indonesia, Moldova, Niger, the Philippines, and Tunisia).

In remittance-receiving countries, banks are the most common type of RSP involved in transferring crossborder remittances, followed by money transfer operators, post offices, and exchange bureaus. In

remittance-sending countries, banks are also the most common providers of cross-border remittance

services, closely followed by money transfer operators, with exchange bureaus ranking third.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(4)

8

March 22, 2012

(5)

10

March 22, 2012

(5)

11

March 22, 2012

Topic

Country

Monitoring

Worldwide

Regulation

Regulation

Prices

Prices

Worldwide

Worldwide

Worldwide

Fact

Data collection from non-bank RSPs appears to be influenced by the requirement for partnerships with

banks. Central banks are more likely to collect data from non-bank RSPs in countries that do not require a

non-bank RSP to partner with a bank. MTOs and post offices in developing countries are more likely to

report inflows to the central bank in countries that do not require non-bank RSPs to operate in partnerships

with banks.

Three-quarters of central banks in remittance-receiving countries reported being involved in developing or

implementing national policies related to AML-CFT. However, the central bank enforces sanctions in just

under one-third of the remittance-receiving countries, while a separate national authority specifically

charged with preventing money laundering enforces sanctions in 34% of these countries, and the ministry of

finance is involved in 19% of these countries. In nine (12% of) remittance-receiving countries, the first two

institutions work together to enforce sanctions; in three of these countries, the two institutions also work

together with the finance ministry. The ministry of finance is involved in enforcing anti-money-laundering

sanctions in nearly one-fifth of remittance-receiving countries. Other national or regional entities involved

in enforcing anti-money-laundering sanctions include the financial intelligence unit, the financial system

superintendency, the criminal prosecutor, the ministry of justice and anticorruption commission, and various

other judicial, anticorruption, and financial intelligence units.

In remittance-sending countries, just over half of central banks (19 out of 35) surveyed indicated that they

were involved in developing or implementing AML-CFT regulations. Central banks in considerably fewer

(just over one-fifth of) remittance-sending reported being involved in enforcing AML-CFT sanctions.

The majority of central bank respondents in both remittance-receiving and -sending countries cited high

cost as the top single factor inhibiting migrants from using formal channels for remittance transfers. After

high cost, lack of a bank branch near the intended recipient, and recipients'/senders' lack of access to bank

accounts, ranked as the second most cited impediments overall, although for remittance-receiving countries

recipients' mistrust of and/or lack of information on electronic transfers ranked nearly as highly. For

remittance-source countries, senders'/recipients' lack of valid ID ranked as highly. Notably, two-thirds of

the remittance-receiving countries' central banks and 46 percent of remittance-sending countries' central

banks cited factors that, taken together, indicate mistrust of/or lack of information on and access to

financial systems, products, and institutions are major factors inhibiting greater access to formal channels.

For the Sub-Saharan African countries' central banks that participated in the survey, high cost was most

often cited as the top factor inhibiting migrants from using formal channels for remittance transfers. 68% of

Sub-Saharan African countries' central banks cited high cost as a major inhibiting factor, while absence of a

bank branch near the beneficiary and recipients' lack of access to bank accounts were second- and thirdSub-Saharan Africa highest ranking factors (cited by 64% and 61%, respectively). Although central banks in Sub-Saharan

Africa reported the same top seven factors as inhibiting the use of formal channels as did all surveyed

countries, a correspondingly higher share of Sub-Saharan African respondents cited these factors, with the

exception of mistrust of/or lack of information on electronic transfers.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(5)

12

March 22, 2012

(5)

12

March 22, 2012

(5)

12

March 22, 2012

(5)

13

March 22, 2012

(5)

13

March 22, 2012

Topic

Country

Prices

Worldwide

Prices

Prices

Monitoring

Monitoring

Transaction

Method

Prices

Prices

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(5)

15

March 22, 2012

(5)

15

March 22, 2012

(5)

16

March 22, 2012

Sixty-five percent of central banks in remittance-receiving countries and 31 percent of central banks in

remittance-sending countries cited better statistics and studies on migration as the area most in need of

attention. Better statistics on remittances was cited by a similar share of respondents in both groups (61

percent and 29 percent, respectively).

(5)

16

March 22, 2012

A significantly higher share of central banks in Sub-Saharan Africa (79 percent) than in remittancereceiving countries as a while (65 percent) cited better statistics and studies on migration and better

Sub-Saharan Africa statistics on remittances as the areas most in need of attention for more efficient and secure transfer and

delivery of migrant remittances.

(5)

17

March 22, 2012

(5)

18

March 22, 2012

(5)

18

March 22, 2012

(5)

18

March 22, 2012

Worldwide

Worldwide

Worldwide

Worldwide

Fact

69% of remittance-receiving countries that require an MTO to operate in partnership with a bank cited high

cost as a factor inhibiting the use of formal remittance channels, compared with 44% of countries that do

not require such a partnership. With the exception of the Bahamas, Oman, Portugal, Russia, and South

Africa, no remittance-sending country reported requiring MTOs to operate in a legal partnership with a

bank. Requiring MTOs and post offices to work in partnership with banks is usually associated with a

perception of high remittance costs. A high cost of remittance services, cited as the top factor inhibiting the

use of formal channels by a majority of central banks in developing countries, appears to be related to the

extent to which money transfer companies and post offices are required to operate in partnership with

banks in order to receive remittance inflows.

The share of central banks in remittance-receiving countries citing remittance costs as a factor inhibiting the

use of formal remittance channels is 12 percentage points higher in those countries where the recipients are

required to convert remittances into local currency than it is in countries that do not have a similar

conversion requirement. Tighter exchange controls are associated with the perception of high costs as a

factor inhibiting the use of formal remittance channels.

Legal requirements for non-bank providers of remittance services such as money transfer agencies,

exchange bureaus, and post offices to operate only in partnerships with banks are more common in

countries with tighter exchange controls. Greater freedom of money transfer agencies and post offices to

operate independently of banks can increase the degree of competition in the remittance market and thereby

put downward pressure on costs. Allowing a variety of well supervised and appropriately regulated RSPs

to operate, and liberalizing exchange controls such as requirements for compulsory conversion of

remittance inflows into local currency encourage the use of formal remittance channels, improve

competition in the remittance market, and reduce costs, ultimately benefitting the remittance receivers.

Just under one-third of remittance-receiving countries indicated that there are policy initiatives planned or

underway to expand the outreach of remittance services to rural areas. Developing new technologies for

remittance delivery - mobile phone, Internet, cash cards, ATM - was cited by one-quarter of those

indicating that they have such initiatives as the means of doing so.

Twenty-three percent of central banks in remittance-receiving countries reported having initiatives to

reduce costs, increase competition, and foster the use of formal channels.

With the goal of reducing costs, increasing competition, and fostering the use of formal channels the

following countries have introduced innovative initiatives. Bangladesh allows MFIs to deliver remittances

in rural areas in partnership with banks. It has also introduced an Automated Clearing and Settlement

Developing Countries System for faster, secure, and low-cost delivery of remittances. Ethiopia reported plans to allow institutions

such as post offices and MFIs to offer remittance services. Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Zambia are

encouraging more RSPs to enter the market.

Worldwide

Topic

Country

Prices

Albania

Prices

Prices

Prices

Transaction

Method

Prices

Regulation

Regulation

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(5)

18

March 22, 2012

(5)

18

March 22, 2012

(5)

19

March 22, 2012

(5)

19

March 22, 2012

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

Worldwide

A majority of central banks cite better statistics and studies on migration and remittances as the most

important areas in need of attention to improve the efficiency and security of remittance transfers. In SubSaharan Africa, nearly 80% of central banks cited better statistics and studies on migration and remittances

as the most important areas needing attention.

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

Worldwide

Anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML-CFT) appears to be a high priority

for countries participating in the survey, many of which have recently or are currently putting in place

institutional frameworks and regulations intended to better monitor suspicious cross-border transactions.

Despite this, there seems to be a lack of clarity in the actual application and enforcement of AML-CFT

regulations for remittance service providers (RSPs).

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

Philippines

Fact

The Albanian central bank has introduced an array of measures, including designing a communication

strategy to increase migrants' awareness of banking products and transfer services, instituting bilateral

agreements between domestic banks and their counterparts in important remittance source countries

(Greece and Italy), and encouraging the Albanian post office to establish cooperation arrangements with

post offices and postal savings banks in migrant host countries.

The Philippines' central bank has undertaken measures to increase the financial literacy of overseas Filipino

workers and their beneficiaries, such as holding seminars both locally in the Philippines and overseas,

which complement the predeparture orientation sessions given by the Philippine Overseas Employment

Administration (POEA) that include providing information on available remittance channels as well as

savings and investment opportunities .

In Tajikistan, where migrant remittances are a large share of GDP, the central bank's efforts are aimed at

improving the public's trust in the banking system in order to increase the use of formal channels. Fiji and

Developing Countries Moldova also have programs to boost public awareness and financial literacy campaigns.

Worldwide

Worldwide

Worldwide

Several remittance-source countries (26 percent) reported that they have initiatives to foster the use of

formal channels in remittance transfers. Germany and New Zealand have introduced websites that provide

information on available channels and costs for selected remittance corridors, which can foster transparency

and the use of formal remittance channels. Switzerland provides a brochure with similar information to

migrants. In Spain, the government is working together with associations of banks and saving institutions to

improve transparency and competition in the remittance market, reduce costs, and make it easier and

cheaper to send remittances. The Norwegian authorities are considering possible changes in regulations to

facilitate remittances. Russia has a public campaign underway to increase financial literacy.

High cost is perceived as the top single factor inhibiting migrants from using formal channels for remittance

transfers. A large majority of survey respondents also cited factors that, taken together, indicate mistrust of

or lack of information about financial systems, products, and channels.

The survey [of central banks] also revealed that migrant remittance inflows have been monitored for a

longer time, and in general are better monitored, than remittance outflows. In several countries, there are

large discrepancies in data reporting by different agencies. Although central banks are beginning to pay

attention to new technologies and alternative channels in recording remittance transactions, new entrants to

the market, such as mobile phone service providers, are not yet very active in cross-border remittance

transfers. Only four remittance-receiving countries reported the use of mobile phones in cross-border

remittance transfers at the time of the survey - May, 2008.

Topic

Country

Regulation

Worldwide

Regulation

Monitoring

Monitoring

Monitoring

Monitoring

Monitoring

Worldwide

Worldwide

Fact

Remittance services provided by many of the newer market entrants tend to be unregulated. However, even

remittance transfer activities of as many as 6% of the commercial banks providing these services in

remittance-receiving countries and 11% of the commercial banks providing these services in remittancesending countries are not subject to any supervisory authority.

The existence of a legal requirement that money transfer operators (MTOs) partner with banks is associated

with high remittance costs in remittance-receiving countries. This relationship is more pronounced in SubSaharan Africa. Remittance costs also tend to be higher in countries where it is compulsory to convert

remittance proceeds into local currency.

Migrant remittance inflows are better monitored than migrant remittance outflows and recording of inflows

has occurred for a longer time. Nearly three-quarters of remittance-receiving countries reported that

collection of migrant remittances data began more than five years ago, with 56 percent of the countries

beginning collection of these data more than 11 years ago. In contrast, for remittance-sending countries, the

corresponding figures are lower: 60 percent and 51 percent, respectively.

In a number of remittance-receiving countries, including the Philippines and Rwanda, money transfer

operators (MTOs) do not report data and other information on remittance transfers directly to the central

bank or any other national institution. The main source of remittances data in most countries is the periodic

Developing Countries (ranging from daily to quarterly) reports submitted by commercial banks. In a number of cases, central

banks indicated that MTOs' remittances data are captured indirectly, in the reporting by banks with which

they operate in partnership (some countries have a legal requirement that MTOs partner with banks).

The most commonly cited method in remittance-receiving countries for estimating informal remittances was

propensity to remit and estimates based on data and information collected from household and/or overseas

migrant surveys. This method was cited by 42 percent of those central banks in countries where remittances

through informal channels are estimated. Estimating the share of remittances in overall foreign exchange

transaction volumes, including through surveys, was the next most commonly cited method in remittancereceiving countries for estimating informal remittances (24 percent). In Rwanda, for example, remittance

Developing Countries transfers through informal channels (hand-carried and other means not reported by the banks or money

transfer operators) have been estimated based on the information generated from surveys that try to

determine the origin of currency sold at exchange bureaus by Rwandan residents (that is, the share of

currency exchanged that originates from the diaspora), which is then multiplied by the volume of monthly

purchases by the exchange bureaus.

Data and information collected from household and/or overseas migrant surveys is the top-cited method for

estimating remittance transfers through informal channels: Propensity to remit & other estimates based on

households & overseas migrant surveys; Estimating remittances' share in total foreign exchange transaction

volumes; Estimates of cash carried across borders by visiting nationals at entry points; Estimates of cash

Developing Countries carried across borders by courier/transport companies, collected via surveys by national statistics agency;

Information provided by foreign embassies on labor permits issued to nationals abroad; Estimates based on

the number of workers abroad including via data provided by Department of Labor; "Expert estimates";

Information from newspapers; Estimates based on errors & omissions in the balance of payments.

GCC

Some major source countries for remittances, such as Saudi Arabia, do not report any remittance data in

their balance of payments reporting to the IMF.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

(5)

2

March 22, 2012

(5)

5

March 22, 2012

(5)

5

March 22, 2012

(5)

7, 8

March 22, 2012

(5)

8

March 22, 2012

(5)

9

March 22, 2012

Topic

Country

Regulation

Worldwide

Transaction

Method

Worldwide

Underbanked

United States

GDP

GDP

Volume

Transaction

Method

El Salvador

Mexico

El Salvador

Volume

Worldwide

Transaction

Method

Worldwide

Immigration

Transaction

Method

Volume

Volume

Mexico

Worldwide

Worldwide

Fact

In 33 percent of the remittance-receiving countries where microfinance institutions operate and in one out

of the four remittance-receiving countries where mobile phone service providers operate, remittance

services provided by these types of institutions are not subject to any supervisory authority. There was no

supervisory institution for post offices undertaking these activities in 37% of the remittance-receiving

countries where they operate. Even the remittance services provided by commercial banks in 6% of

remittance-receiving countries are not subject to any supervisory authority. Money transfer operators'

remittance services are reportedly overseen by supervisory services in just over three-quarters of the

remittance-receiving countries in which they operate. In an even higher proportion of remittance-sending

countries, remittance outflows by banks and exchange bureaus are not supervised by any national entity.

Central banks are starting to record transfers through new remittance technologies and channels: 70%

record remittances through money transfer companies; 69% record electronic fund transfers through

correspondent banks; 47% record international money orders through post offices; 45% record

international money orders sent electronically; 42% record bank drafts; 30% record checks issued by banks

abroad; 29% record prepaid and debit cards; 5% record electronic transfer of remittances to the mobile

phone.

Approximately 35 to 45 million adult consumers in the U.S. have no credit history or credit files that are

too thin to be scored.

Remittances in El Salvador represent over 16% of GDP

Remittances represent over 2% of Mexico's GDP

More than 1.3 million people in El Salvador receive remittances

Mexicans and Central Americans are leading the trend of sending money via new technology with 13% of

remittance transactions being sent from a mobile phone

From 2001 to 2007, remittance receipts reported in the IMF's Balance of Payments Statistics Yearbook

more than doubled to US$336 billion.

Wire transfer companies such as Western Union or Money Gram remain by far the most common means of

dispatching remittances with 70 percent of senders reporting that they use such firms. Banks are used by 11

percent while 17 percent of senders use informal means such as the mail or individuals who carry the funds

by hand.

There are approximately 200 million migrants from developing countries living outside their country of

origin. On average, remittances are sent 10 times a year. Rural areas receive 30 to 40 percent of

remittance flows. Remittance are equal to three times net Official Development Assistance to developing

countries. Up to 90 percent of remittance are spent on food, clothing, shelter, health care and education.

Thirty percent of remittance recipients currently use debit or credit cards (50 per cent in some countries).

Transferring remittances using mobile phone technology is becoming a cheaper means of transferring

money. In Uganda and Ghana, remittances have reduced the percentage of poor people by 11 per cent and

5 per cent respectively.

Resources flows to Developing Countries in 2009: foreign direct investment-359 billion, Remittances 307

Developing Countries billion, offi cial development assistance-120 billion, private debt and portfolio equity 85 billion.

Worldwide

Globally, top remittance-receiving countries in 2010 are: India $55 billion; China $51 billion; Mexico

$22.6 billion; Philippines $21.3 billion. Top Remittance Sending countries are United States $48.3 billion;

Saudi Arabia $26 billion; Switzerland $19.6 billion; Russian Federation $18.6 billion.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(5)

12

March 22, 2012

(5)

10

March 22, 2012

(7)

March 22, 2012

(8)

(9)

(16)

March 22, 2012

March 22, 2012

March 22, 2012

20

(23)

March 22, 2012

(12)

1

March 22, 2012

(22)

3, 4

March 22, 2012

(18)

3

March 22, 2012

(18)

3

March 22, 2012

(1)

17

March 22, 2012

(1)

13, 15

March 22, 2012

Topic

Country

Volume

Worldwide

Immigration

Latin America

Volume

Latin America

Transaction

Method

Worldwide

Volume

Worldwide

Volume

Worldwide

Prices

Latin America

Prices

Worldwide

Prices

Worldwide

Prices

Mexico-U.S.

Prices

Prices

Worldwide

Worldwide

Fact

Globally, The World Bank estimates that the worldwide volume of certain cash, asset, and in-kind transfers

made by migrants to developing countries reached $325 billion in 2010. The U.S. Bureau of economic

Analysis estimates that in 2010, $37.1 billion in cash and in-kind transfers were made from the U.S. to

foreign households by foreign born individuals who had spent one or more years here.

Latin America and Caribbean: Total emigrants: 30,403,000. Total Remittances US$67,905 million.

IMF's annual analysis of migrants' money transfers shows year-on- year growth of 6%. Latin American and

Caribbean migants sent $61 billion in remittances to their home countries last year, up 6 % from 57.6

billion in 2010.

Informal transfers are at least half as much as registered remittances. It has been estimated that between

US$100 and 300 billion are transferred informally each year.

Remittance costs have fallen steadily from 8.8 percent in 2008 to 7.3 percent in the third quarter of 2011.

However, remittance costs continue to remain high, especially in Africa and in small nations where

remittances provide a life line to the poor.

Source

Page Number

Date Accessed

(19)

5

March 22, 2012

(20)

March 22, 2012

(21)

March 22, 2012

(17)

2

March 22, 2012

(2)

1

March 22, 2012

The growth of remittance flows to developing countries is expected to continue at a rate of 7-8 percent

annually to reach $441 billion by 2014. Worldwide remittance flows, including those to high-income

countries, are expected to exceed $590 billion by 2014.

(2)

1

March 22, 2012

The total cost of sending remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean reached USD 4 billion in 2002.

That is about 12.5% of the total remittances. The mean value to send USD 200 was 6% through "ethnic

stores', 7% through banks and 12% through money transfer companies like Thomas Cook or Western

Union.

(14)

151

March 22, 2012

(15)

4

March 22, 2012

(10)

1

March 22, 2012

(10)

2

March 22, 2012

(13)

1

March 22, 2012

(11)

2

March 22, 2012

Reducing the cost to 5% of the amount remitted would free up more than a $1 billion next year for some of

the poorest households.

Although the cost of sending remittances is now much lower than in the late 1990s, the rate of decline has

slowed markedly in the past three years. Prices have dropped only slowly despite rapidly growing volume

and increased competition in the marketplace.

The cost of sending the amount of an average remittance to Mexico, now about $400, has come down

somewhat more quickly in recent years, from 6.29 percent of the amount sent in 2001 to 4.4 percent in

2004.

For sending USD 200, 1) The Global Average Total Cost increased from 8.89 percent in the 3Q 2010 to

9.30 percent in the 3Q 2011. 2) The average price of sending money from the G8 countries went up to 8.53

percent, from the 8.4 recorded on year ago. 3) Looking at the regional trends, the LAC region shows the

highest increase, from 6.82 percent in the last iteration to 7.68 percent in the 3Q 2011. 4) The global

average total cost for sending remittances through commercial banks was 13.68 percent in 3Q 2011. MTOs

lost their status of cheapest RSP type to the post offices. MTOs were charging on average 7.36 percent,

while post offices went down to 7.16 percent

By December 2005 the transaction cost paid by migrants to send US$200 to various countries in Latin

America had dropped to 5.6%. Moreover, when taking into account that the average individual transaction

amount is now US$300, the average cost incurred by senders is lower than 5%.