* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Evidence-Based Options for an Oral Health Policy for Older People

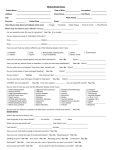

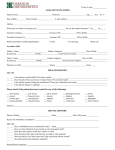

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript