* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

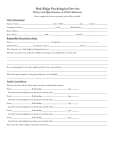

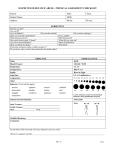

Download HISTORY OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE AND ACTING OUT AMONG

Sexual dysfunction wikipedia , lookup

Substance use disorder wikipedia , lookup

Ego-dystonic sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup