* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Jackson Valley Campaign - Charlottesville Civil War Roundtable

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Chancellorsville wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

First Battle of Lexington wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fredericksburg wikipedia , lookup

Red River Campaign wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Antietam wikipedia , lookup

Stonewall Jackson wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

Eastern Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Seven Pines wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Second Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

First Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

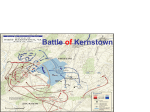

Overview of the 1862 StonewallJackson Valley Campaign T he campaign conducted by Maj. Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley in the spring of 1862 is considered one of the most brilliant in United States, if not world, military history. Vastly outnumbered, and at times facing three Union armies, Jackson managed in less than three months to march his Army of the Valley hundreds of miles and fight a series of engagements (including five pitched battles) in a masterpiece of military art that ultimately created a grand diversion which tied up thousands of Union troops threatening Richmond. Located west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Shenandoah Valley became a major theater of operations throughout the Civil War. Principally, its geological formation (running northeast to southwest) provided an avenue of invasion and counter-invasion for the opposing armies. Additionally, its fertile soil made it one of the most important wheat producing areas of the entire south; literally the "Breadbasket of the Confederacy" whose crops and other produce fed numerous Confederate armies in the field. In the spring of 1862, however, other events occurred throughout the South that thrust the Valley into a more prominent role. Union war efforts that winter and spring had led to significant gains along the Atlantic seaboard and Mississippi River (including the capture of New Orleans). In Virginia, the situation appeared equally grim, as the western part of the state had fallen under Union control. This was followed by the Army of the Potomac's Peninsula campaign, which consisted of a Union army of 100,000 men (commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan) threatening Richmond from the southeast. This plan also called for Gen. Irvin McDowell, with 30,000 men near Fredericksburg, to advance on Richmond from the north. As McClellan's Peninsula Campaign began its advance towards Richmond, a Union force of 35,000 men under Gen. Nathaniel Banks marched into Winchester in early March. Concerned about the lack of protection for Washington, D.C., however, President Lincoln soon ordered troops from Banks' army in the Valley to the capitol's defenses. Within a week more of Banks' forces followed. These moves drastically reduced Banks' army from 35,000 to 9,000 men. Prompted by Gen. Robert E. Lee, military advisor to Confederate president Jefferson Davis, to create a strategic diversion in the Shenandoah Valley, Confederate Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson instead unleashed a vigorous offensive that ultimately paralyzed the Union high command in Washington, kept McDowell in Fredericksburg (preventing him from joining McClellan's offensive against Richmond), and thus wrested the Continued on page 2 The Wright stuff Stonewall Jackson and the 1862 Battle of McDowell, VA Keven M. Walker is the Chief Executive Officer of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation. Mr. Walker came to the Foundation from the Antietam National Battlefield, where he served for 11 years as a Ranger, a Cultural Resources Specialist and the Acting Cultural Resources Program Manager. During that time, Walker served as a member of the National Park Service’s national advisory team on cultural resources and historic preservation and was selected for the GOAL academy, the NPS’s highly competitive leadership program. Says Edwin C. Bearss, Chief Historian Emeritus of the National Park Service, “Keven Walker’s work has been exemplary; ranking him with the best historic preservation professionals I have known since I began my career.” Walker was formerly the Executive Director of The Walker Foundation for Historic Preservation in Charles Town, West Virginia. He has appeared on several Maryland Public Television documentaries focusing on the Antietam battlefield as well as historic homes in Washington County, Maryland. He is the author of “Antietam: A Guide to the Landscape and Farmsteads,” pub- lished in 2010. February Meeting Monday, February 20 ROTUNDA ROOM, WCBR 6 PM Dinner 7 PM Meeting Begins initiative away from the entire Federal campaign. As Stonewall Jackson's small army of approximately 3,500 men marched north from Mt. Jackson on March 22, Confederate cavalry commanded by Col. Turner Ashby engaged elements of Union Gen. James Shields' division on the southern outskirts of Winchester. The skirmish on the 22nd, as well as intelligence gathered from civilians, prompted Ashby to believe that Union forces were leaving the Valley and that only a token force remained. Based on Ashby's information, which later proved false, Jackson determined to strike. The 1st Battle of Kernstown occurred on March 23, 1862 and resulted in a Union victory. This was Jackson's only tactical loss during the campaign. Although he was defeated, Jackson's aggressiveness caused great alarm in Washington. Believing Jackson had a large number of men, Lincoln redirected thousands of Union soldiers back to the Valley. Although this battle was a tactical loss, Jackson achieved his objective by diverting the Federals from Richmond. Following his defeat at Kernstown, Jackson retreated up the Valley to Swift Run Gap, where he was reinforced by Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell's division. As part of the Federal campaign to capture the Shenandoah Valley in 1862, Federal Gen. John C. Fremont moved to threaten the Valley from what is now West Virginia. Leaving Ewell in the Valley to counter Banks' force, Jackson then cleverly deceived the Federals by marching the rest of his small army to the east, and out of the Valley towards Richmond. He then returned his troops to the Valley quickly and secretly by rail to Staunton, in order to launch an unexpected counter offensive against Fremont. Jackson surprised the vanguard of Fremont's army (commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Milroy) on May 8th at the Battle of McDowell. Jackson's victory forced Milroy’s army to retreat westward. At this point in the cam- paign, Jackson now had 17,000 men in his ranks. His next movement was directed northward against Banks, whose main force was located at Strasburg. Taking advantage of the Valley's unique geography, Jackson side-stepped Banks by marching the bulk of his army across the Massanutten Mountain, a 60 mile range that splits the Valley lengthwise, and into the Page (or Luray) Valley. Jackson's objective was a small Union outpost at Front Royal, located at the northern end of the Massanutten. Jackson struck by surprise on May 23rd and quickly overwhelmed the Front Royal garrison. Finding Jackson in his rear, and threatening his line of supply and retreat, Banks had no choice but to order a rapid retreat to Winchester, in hopes of making a stand there. Before Banks could reach Winchester, however, Jackson with a detachment of infantry, cavalry, and artillery cut into the retreating Union column in Middletown on May 24th. The Federals at the head of the line continued north to Winchester, and the column behind fled west out of the Valley. Jackson hoped to follow up his victory and pursue Banks to Winchester, but some of the Confederate troops began to loot the wagons they had captured. This lost momentum allowed the remainder of Banks forces to safely reach Winchester that night. To regain his momentum, Jackson attacked Winchester the following morning on May 25th. Jackson's success at the Battle of Winchester caused Banks to withdraw towards Harper's Ferry and continue his flight into Maryland. Although outnumbered and facing two Union armies, Jackson had cleared the Shenandoah Valley of all Federal troops in just over two weeks. These battles also completed his primary objective of diverting Federal forces away from their main offensive against Richmond. The stunning Confederate victories at Front Royal and Winchester, and others that followed throughout the remainder of the campaign, began to establish the "legend" of the great "Stonewall" Jackson. Reacting to Jackson's presence along the Potomac River, Lincoln devised a plan to destroy the Confederate Army of the Valley. The President ordered three Union columns to converge on the Valley and trap Jackson. "Stonewall" saw the threats approaching and quickly withdrew. Jackson marched his men hard, hoping to escape the three-pronged Union pincer that was converging on Strasburg, to cut off his retreat. Banks pursed Jackson from the rear while Fremont threatened from the west, and Maj. Gen. James Shields's Union force approached from the east. Jackson's bedraggled men barely cleared the town on June 1 as the Union columns converged behind them. Following his narrow escape Jackson continued his rapid march southward up the Valley. Upon reaching Port Republic, a small hamlet at the southern end of the Massanutten, Jackson decided to stand and fight. By controlling the only bridges that spanned the South Fork here, Jackson prevented the Union columns from uniting, and thus he saw an opportunity to strike at each separately. As Fremont was closer, Jackson's plan was to attack and overwhelm him first, and then turn back to defeat Shields. The Battle of Cross Keys occurred on June 8th. The fighting ended with the darkness which allowed the Confederates to maintain their hold on the field and kept the Union columns from uniting. Having successfully held off Fremont, Jackson quickly turned his attention to Shield's smaller force at the Battle of Port Republic on June 9th. Jackson's plan was to leave Ewell at Cross Keys to hold back Fremont, and then concenContinued on page 3 2 trate the rest of his army against Shields at Port Republic and quickly crush him with overwhelming numbers. The logistics of moving most of his men from Cross Keys to, and then beyond, Port Republic, however, proved more difficult than Jackson had anticipated. The day did not go according to plan but Jackson still managed to win his second battle in two days, successfully capping his brilliant spring campaign in the Valley. The retreat of both Fremont and Shields allowed Jackson the freedom to leave the Valley a week later and join Gen. Robert E. Lee's besieged army near the Confederate capitol at Richmond. Battle of Cross Keys Jackson's Valley Campaign was an absolute success. In thirty days, Jackson's men covered 350 miles, defeated three Union commands in five battles, caused 5,000 casualties at a loss of only 2,000 men, and captured much needed supplies. More importantly Jackson had accomplished his main objective of keeping nearly 60,000 Federal soldiers occupied in the Valley rather than advancing on Richmond in conjunction with McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. The 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign made "Stonewall" Jackson the most celebrated soldier in the Confederacy (until he was eclipsed by General Robert E. Lee) and greatly lifted the morale of the Southern home front. SOURCE: https://www.nps.gov/ cebe/learn/historyculture/ overview-of-the-1862-stonewalljackson-valley-campaign.htm Charlottesville Albemarle Civil War Round Ta b l e Launches New Web Site The Charlottesville Albemarle Civil War Round Table is pleased to announce the launch of its new web site. The site is hosted by Non Profit Dynamics of Charleston, South Carolina. The site includes numerous new capabilities for keeping Round Table members informed of current events in the organization, as well as Civil War related events in the surrounding area. Round Table members have access to the entire membership roster, a calendar of coming events, full descriptions of the speakers and their topics, and the ability to register for upcoming lecture dinner reservations. While the site suggests mailing dinner reservation checks, we will continue to accept payment via cash or check at the meeting. Please visit the new site at your earliest opportunity. The address is charlottesvillecwrt.org Upcoming Feb. 20 Keven Walker: Stonewall Jackson and the 1862 Battle Of McDowell, VA ROTUNDA ROOM Westminster Canterbury of the Blue Ridge, Pantops See: charlottesvillecwrt.org Dinner Menu: Choice of prime rib, salmon, or crab cakes Dinner is optional, but reservations are required. Please respond to Sandy von Thelen 971-8567 (W) or 202-7064 (H) or make your reservation on the webpage The Picket Post The monthly newsletter of the Charlottesville-Albemarle County Civil War Round Table. Officers: President, Peyton Humphrey Vice President, Jim Donahue Treasurer, Sandy von Thelen After Action Reports, Sandy von Thelen Program Chairman, Sandy von Thelen Newsletter Production, Duncan Campbell Web Page Liaison, Duncan Campbell Mailing Address: CWRT 13 Canterbury Road Charlottesville, VA, 22903 Telephone: (434) 202-7064 The Picket Post | February 2017 3 A Misrepresentation: Sheridan’s Reaction to Painting of Himself Riding the Battle Line At Cedar Creek When Sheridan saw this now widely publicized painting of himself riding along the line of battle to inspire the men at Cedar Creek and show that he had returned to the army, he reacted vociferously to its inaccuracies. “Now just look,” said Sheridan, “and see how blank ridiculous that man has made me appear. Here I am represented as riding down the line with a flag in my hand and a whole regiment of cavalry as my escort. Why, blank, blank, blank, I’m made to appear like a blank fool. Now the truth is I rode down the line with ‘Tony’ Forsyth; that was all there was to it. No flag. No escort.” Soon after, Sheridan read an article describing his reaction to the artwork. His response: “I wouldn’t have cared so much about it except that [it] makes me swear so [much]. People will think I am in the habit of swearing. Why, blank, blank, blank, you know that isn’t so.” Note that “Tony Forsyth” was Col. James Forsyth, Sheridan’s Chief-of-Staff. The ride along the battle line had been the brainchild of another staff officer. Major George “Sandy” Forsyth (no relation to James) had been the one who suggested that Sheridan show himself to the men when he returned to the Army at Cedar Creek. Sheridan’s appearance along the line of battle rejuvenated the rank and file of the Army of the Shenandoah. Lt. Col. Moses Granger of the 122nd Ohio, Sixth Army Corps recalled the scene: General Sheridan came riding along the line, just in my rear, as I was sitting on a stump, he drew rein, returned our salutes, gave a quick look at the me, and said, ‘You look all right, boys! We’ll whip ’em like h–l before night.’ At this hearty cheers GENERAL PHILIP SHERIDAN broke out, and he rode on passing from the rear to the front of our line through the right-wing of my regiment, and thence westward followed ever by cheers.” Instantly all thought of merely defeating an attack upon us ended. In its stead was a conviction that we were to attack and defeat them that very afternoon. All were sure that “Little Phil” would make it impossible for the enemy to turn our flank, and easy for us to turn theirs.” Scott Patchan SOURCE: https:// shenandoah1864.wordpress.com/ THE BATTLE OF McDOWELL, VA A PREVIEW Some historians consider the battle of McDowell the beginning of Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign, while others prefer to include the First Battle of Kernstown, Stonewall’s only defeat. The battle of McDowell is studied today by military historians for several reasons. At the tactical level, it can be argued that the Union forces achieved a draw. Milroy’s “spoiling attack” sur prised Jackson, seized the initiative, and inflicted heavier casualties, but did not drive the Confederates from their position. At the strategic level, the battle of McDowell and the resultant withdrawal of the Union army was an important victory for the South. The battle demonstrated Jackson’s strategy of concentrating his forces against a numerically inferior foe, while denying his enemies the chance to concentrate against him. Jackson rode the momentum of his strategic win at McDowell to victory at Front Royal (May 23) and First Winchester (May 25). SOURCE: https://www.nps.gov/abpp/ shenandoah/svs3-2.html INCLEMENT WEATHER? Check the meeting status with Sandy von Thelen 971-8567 or 202-7064 4