* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

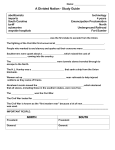

Download t`s astonishing just how small Fort Sumter, S.C., is. Five minutes at a

Survey

Document related concepts

Battle of Island Number Ten wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Donelson wikipedia , lookup

Fort Monroe wikipedia , lookup

Fort Delaware wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

Fort Washington Park wikipedia , lookup

Galvanized Yankees wikipedia , lookup

Siege of Fort Pulaski wikipedia , lookup

Fort Stanton (Washington, D.C.) wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Henry wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup

Fort Fisher wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Port Royal wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Some interiors and gun emplacements of the Fort Sumter National Monument, Charleston, S.C., have been restored by the National Park Service to depict their Civil War state, but the overall look of the fort is far different today. t’s astonishing just how small Fort Sumter, S.C., is. Five minutes at a saunter will take most who walk it across its breadth, from the entrance gate to the far gun line. A dark gray blockhouse impedes those who stroll there today. It encased the command-and-control center during World War II. Fort Sumter was an operational part of the Charleston Harbor defenses from its beginning as the Civil War’s flashpoint to nearly the Cold War, and adaptations made during both World Wars and the Spanish-American War changed the fort. It looks nothing like the night after Christmas in 1860, when MAJ Robert Anderson withdrew his garrison there for better force protection. The outer walls are only one story tall now, shaved from a three-story height. The original interior build- 56 ARMY ■ April 2011 ings are gone. Any brickwork not bashed to smithereens when Union forces returned to reclaim the fort in 1865 was downed by later upgrades. Anderson’s garrison burned most of the wooden structures as the artillerymen ripped them apart one by one for fuel to survive— the cook shack consumed last in the desperation to hang on. At the end of Anderson’s occupation of the fort, the garrison was on short rations that had been cut again. Not much more than a day’s worth was left at that trickle. Water was scarce and bad. Clothing and bedding cloth went to make cartridge casings, which gunners stitched with the seven needles on the property book. Approximately 80 soldiers were isolated there for nearly four months, enduring all the petty problems that being too close for too long brings. Stress made things tighter. Dwindling hope of reinforcement or rescue made things even worse. Gone are the vestiges of how the soldiers endured, but at the fort’s seaward side, Confederate state flags now fly atop a ring of flagstaffs around a taller central flagstaff bearing the U.S. colors. Memorializing the losses on both sides, its design symbolizes restored allegiance under one flag. Despite its physical changes, Fort Sumter remains perhaps the strongest symbol of the Civil War, bookending its course from beginning to end. In early 1861, the situation at Fort Sumter grabbed the nation’s attention and held it. Although other U.S. military facilities in the South faced similar siege situations under varying degrees of menace, Sumter was the most prestigious and received the most press. Its ongoing story was reported extensively in American newspa- pers, and news of it was disseminated worldwide by telegraph taps. It was the story of the day almost every day and became the public focal point in a high-stakes test of wills—national and personal. Great political and strategic questions came to be embodied by the struggle over Sumter. Newspapers, magazines and, uniquely, battlefield photography came to carry significant influence, shaping public opinion and pulling politicians along magnetically. The media assumed a newfangled power, too. The Associated Press came into its own during the war—a media game-changer on par with CNN’s 24/7 news cycle breakout during the Gulf War. Meanwhile, local Charleston tensions were heightened by the city’s firebrand paper The Charleston Mercury, pro-secession and pouring fuel on the city’s rage. April 2011 ■ ARMY 57 An artillery projectile is stuck in an interior wall of Sumter, apparently fired during the heavy Union barrage in the late stage of the Civil War as Northern forces sought to retake the fort. A heavy gun on its carriage points toward Charleston Harbor from Battery Park. and allegations that he also drank too much and led too little. He was replaced by MAJ Anderson. The threat skyrocketed, however, when the South Carolina legislature ratified the December 20, 1860, secession declaration passed by a state convention. It was the first state to secede, and it was the cornerstone of the Confederacy. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama and Georgia followed quickly. The issue of Fort Sumter increasingly chained both sides to their own honor. Like a duel, events there would decide whose honor was upheld. And, as in duels of the day, honor could be upheld without bloodshed. Above, the harbor side of Fort Sumter: Tied up at the wharf is one of the contractor vessels that shuttles visitors to the site. The open area largely was ringed and dotted by living quarters and various shops when the Charleston garrison withdrew there in 1861, and the exterior was three stories tall. Right, the monument’s displays include heavy cannons used during the Civil War. At Fort Sumter, the matter centered on when, or whether, federal forces would abandon it and accede to secessionist demands that U.S. authorities turn over all federal facilities, including military establishments, within a seceding state—imposed first by the state of South Carolina and later the centrally organized Confederate States of America (CSA) in its nascent form. o long as the fort held, symbolic accession to the demands and declarations pressed upon it was denied, and, by extension, denied to the fundamental questions orbiting secession itself. For both sides, it became a matter of honor at the state and national levels, more so directly at the scene of the Charleston standoff. There, honor was close and personal, and it was manifested in many ways. The affair was conducted in a rather gentlemanly fashion, up to a point. Personal honor S Civil War-era mortars sit in Charleston’s Battery Park. Batteries there were at too great a range for the attack on Fort Sumter, but the site served as an observation point for the citizens of Charleston. 58 ARMY ■ April 2011 any on the southern side believed in a best-case scenario, which was that the federals, afforded generous fanfare and flourish, would march out peacefully— drums beating and a transport ship waiting. The U.S. flag would be lowered, folded and taken with them, and the new Confederate flag would be raised, achieving the desired end state. Neither side wanted to shoot first, nor did the South want its actions to appear barbarous. The Sumter garrison’s mission was to fly the flag for as long as possible, allowing time for a political settlement, or holding out at least until the newly elected President, Abraham Lincoln, took office and issued further orders. Anderson’s original directives were ambiguous, with versions delivered verbally at several political command levels. Taken in net worth, however, the orders as Anderson understood them ran along this general track: Don’t start a war by shooting first, and, by extension, don’t raise southern hackles in other ways; hold out as long as humanly possible to buy time and not disgrace the flag, and take necessary actions to protect the garrison. As it played out, the last general order was viewed differently in Washington after MAJ Anderson spirited his garrison from Fort Moultrie, S.C., to Fort Sumter less than a week after South Carolina’s secession. Anderson’s move frazzled hypersensitive political nerves—everything at the fort was M among America’s officer corps (though it was splitting apart) drove duty. Personal honor also strongly led civil conduct among the upper economic classes, especially in the South. The direct threat to Fort Sumter began as occasional less-than-cordial brushes in Charleston’s streets. The threat level spiked when, in November 1860, the then-commander of the Charleston garrison, brevet COL John C. Gardiner, tried to take ammunition from the arsenal, which was situated in the city. A crowd turned back the fort’s working party, and the ammunition was returned to the arsenal. The incident caused secondary effects: Fort Sumter would be short of ammo when it was needed, and the commander soon would be sacked, taking into account his behavior during the incident The dark hulk of the fort’s Word War II command-andcontrol center dominates the central portion of Sumter today. OK as long as it stayed quiet. Reaction asserted that the garrison’s move went beyond Anderson’s authority to protect his force, although no specific encumbrances on force protection had been placed on Anderson beforehand. The then-Secretary of War telegraphed Anderson on December 27: “Intelligence has reached here this morning that you have abandoned Fort Moultrie, spiked your guns, burned the carriages and gone to Fort Sumter. It is not believed because there is no order for any such movement. April 2011 ■ ARMY 59 Explain the meaning of this report. J.B. Floyd, Sec’y of War.” South Carolinians viewed Anderson’s move as breaking an agreement (an “understanding,” at least) to keep the status quo, which excluded moving in any direction except away from Charleston. Anderson simply saw a bad tactical military situation and took the most prudent action available. The garrison headquarters at Fort Moultrie could not be defended from ground assault by the number of soldiers he had: nine line officers, one surgeon, 19 NCOs, 48 privates and eight band members (who probably were crosstrained rapidly). The garrison also had about 20 family members and 43 construction workers to consider. ort Moultrie occupies a position across the wide harbor from the city of Charleston on Sullivan’s Island, which was a resort property for Charleston’s elite. Their summer homes crept to the shadows of the fort’s walls, and the island was readily accessible by land. Anderson’s father, MAJ Richard Anderson, had served there during the Revolutionary War (then Fort Sullivan and renamed for the commander and victorious defender of Charleston, BG William Moultrie). Militiamen began to arrive. Picket boats started to guard the water approach. One assault could finish them. It was time to go. Anderson moved everybody—soldiers and family members alike—and all the stores, ammunition and equipment that could be ferried by small boats to the better protection of Fort Sumter. He even took some civilian workers—given a quick loyalty assessment—because Sumter was not yet F The Fort Sumter flag was lowered in 1861 and carried out by the Union commander, MAJ Robert Anderson. He raised it again in 1865 as a retired major general to mark the fourth anniversary of the bombardment that started the Civil War. A gun port faces the harbor from Fort Sumter. The fort’s interior World War II blockhouse today houses a visitor center. A display informs visitors about the Confederate commanding general at Charleston, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. 60 ARMY ■ April 2011 A model in Sumter’s visitor center depicts the fort as it appeared in 1861. April 2011 ■ ARMY 61 Artillery pieces top the wall at Fort Moultrie, S.C. MAJ Anderson withdrew his garrison from Moultrie to Fort Sumter during the night of December 26, 1860, for better force protection. Confederate forces quickly occupied Moultrie and held Sumter under its guns. fully completed. Aside from two captains, he gave the garrison only 30 minutes notice in order to better preserve the plan’s security and keep the clamor short. The operation was complex and studded with deceptions and feints. For example, boats carrying family members first went to another harbor fort, which was observable from Charleston, and the women and children appeared to bed down for the night. Observers thought they had arrived in anticipation of the garrison following. Wrong. The boats headed back out as if they could be returning to Moultrie and veered instead into Sumter. Some might call this audacious; the people of Charleston considered it skullduggery. It was a good plan. s the night wore on, each subsequent lift had to avoid the picket boats for a couple of miles to make Sumter, rowing back and forth to shuttle cargo and passengers. Yet the move was accomplished undetected. The last men to leave Moultrie spiked the guns and set gun carriages ablaze. The flagstaff also was broken to deny it to the enemy for his flag. One very old retired sergeant and his wife were left behind at an emplacement that was long their home with the request that South Carolina forces treat them with dignity. They did. Militia occupied the abandoned facilities, and Anderson himself raised the U.S. colors above Fort Sumter at noon while the chaplain prayed and soldiers saluted. Sumter’s situation stabilized, politically and tactically, into a siege without fire. The garrison found itself on an island—occupying a speck in Charleston Harbor that was a persistent irritation to southerners and increasingly isolated from Washington. A Artillery pieces are displayed at Fort Moultrie, which is maintained by the National Park Service as part of the Fort Sumter National Monument. 62 ARMY ■ April 2011 identified and signals attempted, but batteries manned by the South Carolina militia and cadets from The Citadel (The Military College of South Carolina) by then had spotted it and opened fire, eventually hitting the ship with three rounds, which did no significant damage. (In historical fact, of course, these were the first shots of the Civil War, but the eventual direct attack on the fort received that credit, arguably by choice at the time to avert pressure for retaliation, although southern delegations raised hell about it.) After a while, the situation settled into an odd normalcy. Charleston remained angry but accepted that the fort would not hold out for long, based on what was being heard in Washington and from federal envoys allowed to visit the fort over time (another gentlemanly act). The trouble was that the federals never hit the time line, no matter how often it was adjusted and accommodated. During the early stages, not only could Sumter receive emissaries, it could use the telegraph and mail, and for a while fresh beef and other foods were delivered under preexisting contracts. Things got uglier after Washington sent an unsuccessful rescue mission. The steamship Star of the West was loaded with provisions and some 200 fresh troops during the first days of January 1861 and churned out of New York Harbor. At the last moment, the contracted civilian vessel had been chosen as a replacement for the USS Brooklyn, diminishing, to the extent it was possible, any fallout from a direct military clash involving a flagged U.S. warship. The ship slipped into Charleston Harbor under the cover of darkness on January 9, but Anderson had not been made aware of the mission, and he had not at that time specifically requested resupply. Soldiers on watch were surprised by its arrival. Anderson was awakened and called for the guns to be manned. The ship was Passageways inside Fort Moultrie’s thick exterior wall connect magazines and other areas. s the South Carolina batteries hurled shots at the Star of the West, Anderson held fire, seeing it within his orders and as his personal duty to avert an exchange of fire (and near-certain nied. She rebutted with a somewhat war) to the best of his abilities. The scolding appeal to Pickens. Goaded by ship turned about and steamed away Mrs. Anderson, he thought better of his with the men aboard wondering why pettiness and approved Hart’s pass. Fort Sumter had not chosen to help itShe was met at the sally port and tenself. derly carried into the fort by her husNo other attempt would be made to band. She told him that she had come relieve or rescue Sumter until well to put the sergeant at his side once past the eleventh hour. Federal ships again, which was the best thing that (military, and flagged as such this she could do for him. time) arrived off Charleston Harbor Two hours later, she left on the tide, and anchored at a rendezvous point having delivered her reinforcement. that had a particularly good view of She returned to New York by way of the smoke rising from Fort Sumter on Washington, congratulated for her the day Anderson hauled down the courage and honor but much more ill. flag, folded it and marched out with it. After taking office, Pickens had raced The story goes that the only actual to Charleston as state commander in reinforcement Anderson ever received chief. He had secessionist fever and was a single retired sergeant, personwas a political product of it. He set ally delivered by Anderson’s wife, militia units to improving or building Elizabeth. A general’s daughter, she fortifications. Many working cannons A frame hoist inside Moultrie shows was in New York City and sick. When and mortars were captured and emhow artillery pieces were raised from word reached her about the Sumter placed around Sumter, and cadets from and lowered onto their carriages. move and her husband’s peril, she unThe Citadel brought their own heavy dertook extraordinary measures and guns. painful travel to make the delivery. She left her sickbed South Carolinians also constructed a “floating battery”—a and tracked down an old and trusted sergeant, Peter Hart, barge-like vessel armored with thick planking and armed who had served with Anderson during the Mexican-Amer- with cannon fired through ports. It could get close, perhaps, ican War and lived in New York. She went to his home, and was particularly feared. asked him to leave his wife behind, risk his life and accomEventually, safe passage was requested for the Sumter pany her to Charleston, then onward to Sumter. And she family members and given. They boarded a northbound put the most difficult request to him: She asked that he ship. stay with the garrison to be at her husband’s side and help Despite his energy in getting things up and running and him because she was too ill to stay. his zeal for the cause, Pickens really didn’t want the reAlmost instantly, Hart agreed. Disguised as a servant, he sponsibility of ordering the first shot if it came to it, so he traveled by train with her. In Charleston, Mrs. Anderson pe- was not disappointed when the new Confederate governtitioned for passes to proceed to the fort. She received one ment took charge at Charleston and dispatched a profesfrom the newly elected South Carolina governor, Francis W. sional to the job site. This was Pierre Gustave Toutant Pickens, whom she knew personally, but Hart’s pass was de- Beauregard, a former U.S. Army officer, politically con- A April 2011 ■ ARMY 63 The visitor center at Fort Moultrie shows the fort’s history, which stretches back to the Revolutionary War. nected and a newly minted CSA brigadier general, one of the first generals commissioned by the Confederacy. Beauregard was pure, distilled Louisiana aristocracy on the hoof—short in stature, long in pedigree. He was an unapologetic dandy, fastidious in appearance, and he glided into Charleston society like Cajun smoke. On his first night in town, he went to the theater to mingle. He was a hit. Ladies of the city sent food baskets to his headquarters. Men sent liquor and cigars. Beauregard and Anderson were colleagues and acquaintances, if not friends. Both were veterans of the MexicanAmerican War and had served under LTG Winfield Scott, and both were graduates of West Point. (Anderson had, in fact, taught Beauregard at West Point.) The Confederate commander knew that Anderson would not walk out of Sumter in disgrace. Over time, Beauregard agreed to terms that would allow the federal garrison to quit the post and walk out after a 100-gun salute. (Anderson had taken a hard-line stand on the number of guns.) t one point, the southern commander sent a load of champagne and victuals to Anderson, but he returned it, saying he could accept nothing more than the agreed rations. Again, it was a rather gentlemanly affair, but the situation finally heated to the boiling point—constantly stoked by the garrison’s failure to leave on several dates (promises in the southern view and estimates in the northern). Time finally ran out. The Confederate government, fed up and fearing that the North would yet pull something, ordered Beauregard to seek surrender once more. If last-ditch negotiations failed, he was to open fire at the first advantageous moment. The talks failed. At 4:30 A.M., on April 12, a mortar shot arced toward Sumter and exploded in the air. It was the signal to commence fire. The barrage continued all that day and half the next. Little meaningful damage was imposed on the fort’s hard outer shell, but several blazes started inside the fort. The flagstaff was knocked down and reerected under fire. The flag had been singed, but no casualties occurred at A 64 ARMY ■ April 2011 Sumter during the artillery exchange. Two men, however, died in the ceremony that followed. Confederate envoys again went to Sumter, and Anderson agreed to an “evacuation” on April 14. Terms included the 100-gun salute, and the two soldiers died in accidents that occurred during the salute, causing the gunners to fall short of the 100 mark. Anderson marched out with the garrison flag, and the men were put on a boat headed to New York. He was certain that he would return to face court-martial or severe censure, but he was promoted to brevet brigadier general and lauded roundly. The new war needed new heroes. President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to wear blue, right the wrong and keep the Union together, asking for six month’s duty in a war that most expected to be short. Anderson would go on to achieve the rank of major general. He retired during the war, mainly because of bad health that set in at Sumter including, by some accounts, what we call today post-traumatic stress. In the summer of 1861, Beauregard was a leader of victorious Confederate forces at the First Battle of Manassas/ Bull Run. The Confederacy held Fort Sumter until the last stages of the war. In 1865, MG William T. Sherman’s strong Union forces swung up the Atlantic coast from their “march to the sea” and headed to Charleston, among other cities, bent on issuing a little payback. By sea and land, Sumter was bombarded on a scale unimaginable in 1861, reducing much of it. The Confederate garrison, however, did not evacuate under fire. It, too, held out. A concrete slab memorializing the soldiers’ stand was dedicated by the Daughters of the Confederacy in 1929, and it remains inset astride Fort Sumter’s entrance. Anderson donned his uniform one last time to raise the original garrison flag above Fort Sumter during a ceremony held on April 14, 1865, four bloody years to the day from the Sumter evacuation. That night, President Lincoln was shot, dying the next day as the last casualty of the war that began and ended with the U.S. flag flying above Fort Sumter, a battered but enduring symbol. ✭