* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Lesson 1-- Introduction. Review of Supply and Demand

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

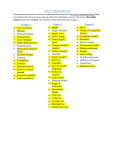

Econ 217 Lesson Plans Lesson 1‐‐ Introduction. Review of Supply and Demand Who I am Pass out syllabus and go over Pass out sign up sheet Undergrad Inst. Major Had Calculus / Had Intro Micro / Had Other Econ Interests Hand out homework Buy a good calculator – one with ln, e, y^x Y = a + bX Y and X are variables. a and b are parameters. Example: Fahrenheit Temperature = 32 + (9/5)*Celsius Graph this. a=32 – this is the intercept. b=9/5 – this is the slope – it is the change in Fahrenheit / change in Celsius. For example, if Celsius goes up 50 degrees, Farenheit will rise 90 degrees. Note: Change in = Δ Slope = ΔY / ΔX = Rise over Run. Note: in Economics, there are often several variables affecting Y. Show a scatterplot. Stateʹs demand for natural gas: Y = Y(Price, Winter Temperatures, Income, Cost of Living) Positive/Negative Slope Y = f(x) = a + bx + cx^2 Graph c<0, c>0 What is the slope of this curve? Example: Y = f(x) = 50 ‐20x + 3x^2 X 0 1 2 3 4 5 Y 50‐20*0+3*0^2 = 50 33 22 17 18 25 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Calculus Find the change in y for a small change in x. dy/dx = ʺthe derivative of y with respect to xʺ Rules for taking a derivative: 1) the derivative of a constant is zero. 2) the derivative of cx^n = n*c*x^n‐1 Example: y = f(x) = a + bx + cx^2 dy/dx = 0 + b + 2cx Compute dy/dx = ‐20 + 6x What is the slope at x=0: ‐20 What is the slope at x=1: ‐14 What is the slope at x=3: ‐2 What is the slope at x=4: 4 Example: Y = 7x^3 + 5x^4 dY/dX = 3*7*x^2 + 4*5*x^3 *************************** Suppose Y is a Function of X and Z: Y = 10 + 3x + 4z How would we graph this? Graph this if z = 1. Graph this if z = ‐2. What is the slope of your lines? Partial derivatives: find the derivative holding Z constant. dY/dX = 0 + 3 + 0 More examples: Y = ‐12 + 2x^3 + 3Z^4. Find dY/DX. Find dY/dZ. Y = 8(X^2)(z^3). dY/dX = 16xz^3. dY/dX = 24x^2(z^2) That’s it. Chapter 1 Assumptions generally used in this course: 1) Persons are goal‐oriented or self‐interested – they have desires and preferences for goods and outcomes. 2) People are rational. Careful, deliberative process to make choices. Make choices based on the belief that the benefits of their action exceed the costs. 3) People face scarce resources and therefore must make choices. Opportunity cost – Explicit + Implicit Costs (value of the next best opportunity). What is your cost of being here tonight? – Tuition plus value of next best opportunity Sunk costs – costs that have already been spent and cannot be unspent. Ex. Suppose I buy plane tickets to Hawaii. I then find out that my brother is getting married at the time of my vacation. Should I take the costs of the tickets into my decision about attending my brother’s wedding? No. Chapter 2 Demand curve: relationship between price of a good and consumer’s demand for the good. Law of demand: the lower the price of the good, the larger the quantity demanded – i.e., demand curves slope down. What else effects the quantity demanded? For example, other than its price, what effects my demand for Taco Bell? Price of other goods: Substitutes: Price increases in good A raise demand for good B Complements: Price increases in good A raise demand for good B Income: Normal goods: Higher income raises demand for good A. Inferior goods: Higher income raises demand for good B. Lesson 2 – Supply and Demand / Theory of Consumer Behavior Announcements: • Pass out HW ‐‐ HW due Monday • In‐class midterm / quiz in two weeks. • If anyone would like to join a study group, please email me and I will give you names of other people interested in meeting. If anyone has a study group with a regular meeting time and is willing to accept more members, let me know. More on Supply and Demand Lets graph my demand for Taco Bell Burritos: Burritos = 10 – 2P – Income/10000. Graph this for income = 20000. Graph this for income = 80000. What is the slope of the demand curve? What moves you along the demand curve? What shifts the curve? (change in preferences). Supply curve: relationship between the price of a good and the quantity that firms will supply. Law of supply: the higher the price of a good, the higher the quantity supplied – i.e., supply curves slope up. What else would affect supply (i.e. shift the curve)? Suppose: Qs = ‐10 + 3P Qd = 50 – 2P Graph the supply and the demand curve. Discuss equilibrium. ‐10 + 3P = 50 – 2P 5P = 60 P = 12 Q = 26 What would happen if we put a price ceiling of 10? 15? What would happen if we put a price floor of 15? 10? Suppose the government added a $2 tax per burrito to be collected from consumers – new demand curve would be shifted down by $2: Old demand curve: Qd = 50 – 2P Qd – 50 = – 2P P = 25 – Qd/2 New demand curve: P = 23 – Qd/2 Or Qd = 46 – 2P Solve for new equilibrium: ‐10 + 3P = 46 – 2P 5P = 56 P = 11.20 – note, this is the price that Taco Bell receives. Q = 23.6 P = 13.20 – this is the full price the consumer pays, including the tax. ***** Now, would this be different if the tax is collected directly from Taco Bell – new supply curve would be shifted up by $2: Old supply curve: Qs = ‐10 + 3P Qs + 10 = 3P P = Qs/3 + 3.3333 New supply curve: P = Qs/3 + 5.3333 Or Qs = ‐16 + 3P Solve for new equilibrium: ‐16 + 3P = 50 – 2P 5P = 66 P = 13.20 – note, this is the price that the consumer pays. Q = 23.6 P = 11.20 – this is the full price that Taco Bell receives after it pays the tax. LESSONS: 1) IT DOESN’T MATTER WHO PAYS THE TAX – THE EFFECTS ARE THE SAME FOR BOTH THE CONSUMER AND PRODUCER. 2) BOTH THE CONSUMER AND THE PRODUCER SHARE IN THE BURDEN OF PAYING THE TAX. ***** Elasticity: %ΔA/%ΔB %ΔA = A1 – A0 / A0, alternatively %ΔA = A1 – A0 / 0.5(A0 + A1) Price elasticity of demand: %ΔQd/%ΔP o Will be a negative number Price elasticity of supply: %ΔQs/%ΔP o Will be a positive number Income elasticity of demand: %ΔQd/%ΔIncome o If negative, then it is an inferior good. If positive, then it is a normal good. Cross‐Price elasticity of demand: %ΔQdA/%ΔPB o If negative, then it is goods are complements. If positive, then goods are substitutes. “Elastic” > 1 “Inelastic” <1 Note, these are in absolute value terms. “Unit‐Elastic” = 1 Draw perfectly elastic and inelastic curves. Note: need to compute these holding other variables constant. Note: elasticity is not constant along a straight line demand curve: P = 100 – 5 Qd Compute price elasticity between Q = 10 and Q=11; between Q=2 and Q=3 ***** Chapter 3) Consumer Choice Utility = Amount of Happiness Indifference Curves = combinations of goods x and y that give me the same amount of utility Marginal Rate of Substitution = the amount of good y that I am willing to give up to get one more unit of good x, with no change in utility – that is, it is the slope of the indifference curve. Diminishing MRS – as I get more good x, I become less and less willing to give up much y to more x – this is generally true. Show Constant MRS. Perfect Substitutes. Note: the MRS for perfect substitutes is not diminishing. Ex: Reading Two Newspapers versus Watching one Hour of TV. Graph my utility curves. Perfect Compliments. Ex. PB and J – I like it 2 to one. Graph this: Why indifference curves can’t cross Budget Constraint / Line = the combinations of goods x and y that can be purchased given the consumer’s income or budget Px*x + Py*y = Income X= Teachers, Y=Policemen. Px = $30,000, Py = $40,000 and city budget = $1,200,000 30x + 40y = 120 OR 30*teachers + 40*policemen = 1200 slope intercept form: 40y = 1200 – 30x y = 30 – ¾ x Graph this. Everytime I give up one teacher, I can buy ¾ of a policemen. The opp. Cost of 1 teacher is ¾ of a cop. What happens when city’s budget rises? What happens when price of cops rises? What happens when price of teachers rises? What happens if federal government agrees to pay 10% of teacher’s salary? What happens if federal gov’t pays for 2 cops? Consumer choice = finding the utility maximizing (x,y) given income and preferences. Show why MRS = Price Ratio = Px / Py MRS = Marginal Benefit of getting x – how much y I am willing to give up to get one more x. Price Ratio = marginal cost of getting x – how much y I have to give up to get one more x. Lesson 3 -- Individual and Market Demand Budget Constraint / Line = the combinations of goods x and y that can be purchased given the consumer’s income or budget Px*x + Py*y = Income X= Teachers, Y=Policemen. Px = $30,000, Py = $40,000 and city budget = $1,200,000 30x + 40y = 120 OR 30*teachers + 40*policemen = 1200 slope intercept form: 40y = 1200 – 30x y = 30 – ¾ x Graph this. Everytime I give up one teacher, I can buy ¾ of a policemen. The opp. Cost of 1 teacher is ¾ of a cop. What happens when city’s budget rises? What happens when price of cops rises? What happens when price of teachers rises? What happens if federal government agrees to pay 10% of teacher’s salary? What happens if federal gov’t pays for 2 cops? Consumer choice = finding the utility maximizing (x,y) given income and preferences. Show why MRS = Price Ratio = Px / Py MRS = Marginal Benefit of getting x – how much y I am willing to give up to get one more x. Price Ratio = marginal cost of getting x – how much y I have to give up to get one more x. New way of looking at the same idea: Total Utility – level of happiness given x and y. Marginal Utility – change in happiness (total utility) with one more good x or one more good y. MUx / Px = how much more happiness I would get if I spent one more dollar on x = Bang for the buck. Suppose U = Uoranges + Ulemons Price of Oranges = $2 Oranges 1 2 3 4 5 Total Utility 20 35 47 51 52 Marginal Utility 20 15 12 4 1 MU / Price = Bang for the Buck 10 7.5 6 2 0.5 Marginal Utility 36 33 21 18 3 MU / Price = Bang for the Buck 12 11 7 6 1 Price of Lemons = $3 Lemons 1 2 3 4 5 Total Utility 36 69 90 108 111 Suppose I have $18 to spend Income Left Lemon 15 Lemon 12 Orange 10 Orange 8 Lemon 5 Lemon 2 Orange 0 Utility maximization occurs when: MUx / Px = MUy/Py Implies: MUx / MUy = Px / Py Thus, MUx / MUy = MRS Solving for the optimum using calculus – not on test: MUx = dU/dx (partial derivatives as we are holding y constant) MUy = dU/dy (holding x constant) Discuss food stamp problem. 1) From Budget Sets / Indifference Curves to Individual demand curves Draw a budget set with Px1. Show the optimal choice. Change to Px2. Show the new optimal. Graph this in Px / Qx space. 2) Income and Substitution Effects Px falls Qx Qy (Assuming X and Y are normal goods) Income Effect + + Subs Effect + ‐ Total Effect + ? If income effect dominates subs effect for good y, then the goods are complements. If subs effect dominates income effect for good y, then the goods are subs. Discuss and redraw Figure 4.3 on page 90 Px falls Qx Qy (Assuming X is an inferior good and Y is a normal good) Income Effect ‐ + Subs Effect + ‐ Total Effect ? ? Giffen good – if good x is an inferior good, and income effect dominates subs effect, then demand curve for x will slope up. Very rare. 3) From Individual to Market demand curves Case of identical consumers. suppose P = 100‐5Q for one consumer and you had 7 identical consumers Graph this. Show that market demand curve is: P = 100‐(5/7)Q (i.e., the slope is 1/7th its former). Alternatively: Individual: Q = 20 – P/5 Market: Q = 7*Individual = 140 – (7/5)*P **** Case with different types of consumers – Talk about figure 4‐7 on p.97 Consumer Surplus Note Consumer Surplus = sum of marginal benefits – sum of marginal costs = total benefit – total cost Using the demand curve above, compute the CS if P = 50. Taxes, Subsidies, Rent Control, Minimum Wages, and Consumer Surplus Lesson 4 -- Individual and Market Demand (cont…) Collect HW1, distribute HW2 Discuss Next Weeks Exam –practice midterm will be on the website Go over HW 2.12 Discuss Next Weeks Exam –practice midterm in on the website 2) Income and Substitution Effects Px falls Qx Qy (Assuming X and Y are normal goods) Income Effect + + Subs Effect + ‐ Total Effect + ? If income effect dominates subs effect for good y, then the goods are complements. If subs effect dominates income effect for good y, then the goods are subs. Discuss and redraw Figure 4.3 on page 90 Px falls Qx Qy (Assuming X is an inferior good and Y is a normal good) Income Effect ‐ + Subs Effect + ‐ Total Effect ? ? Giffen good – if good x is an inferior good, and income effect dominates subs effect, then demand curve for x will slope up. Very rare. How would one estimate a demand curve ‐ discuss supply and demand intersections ‐often only know local elasticity Using Elasticity to Predict Changes in CS Currently Q = 20, P = 5, and price elasticity of demand = 0.4. Suppose the government is going to subsidize the product so that price falls to 4. Compute the new quantity and the approximate change in CS (assuming a linear demand curve). % change in P = (4‐5)/4.5 = ‐20% % change in Q / % change in P = ‐0.4 % change in Q / ‐ 20% = ‐0.4 % change in Q = ‐0.4 * ‐0.2 = + 0.08 New Q = 20 * 1.08 = 21.6 Change in CS = 20 * 1 + ½ * (1.6)*(1) = 20 + 0.8 = $20.8 Discuss why intersection of supply and demand curve is most efficient solution (benefit = cost. Taxes and Consumer Surplus with a perfectly elastic supply curve – show that lost CS is greater than revenue generated. – Define and show deadweight loss. Subsidies and Consumer Surplus with a perfectly elastic supply curve – show that increased CS is less than cost to government generated. – show deadweight loss. Show why consumers would prefer a lump‐sum transfer to a equal‐cost subsidy – note – this implies that the subsidy scheme has a deadweight loss relative to the transfer system Note the same thing is true for excise (sales) taxes relative to lump‐sum taxes. Lesson 5 -- Using Consumer Choice Theory Topics today: Lump‐sum transfer to a equal‐cost subsidy Elasticity along a straight line demand curve Intertemporal Choice Risk and uncertainty Subsidies versus lump‐sum transfers Show why consumers would prefer a lump‐sum transfer to a equal‐cost subsidy – note – this implies that the subsidy scheme has a deadweight loss relative to the transfer system Note the same thing is true for excise (sales) taxes relative to lump‐sum taxes. In other words, (assuming consumerʹs know their own preferences, and are rational, and assuming there are no externalities, and the good is sold in a competitive market) to improve consumerʹs welfare, the government shouldnʹt attempt to distort choices by subsidizing some goods and taxing others. ‐‐ assuming consumerʹs know their own preferences and are rational, there are no externalities, and the good is sold in a competitive market. Note: elasticity is not constant along a straight line demand curve: P = 100 – 5 Qd Graph this. Compute price elasticity between Q = 10 and Q=11; between Q=2 and Q=3 Q = 10 Æ P = 50 Q = 11 Æ P = 45 Using Arc‐Formula: %ΔQ / %ΔP = +10% / ‐11% = ‐0.90 Q = 2 Æ P = 90 Q = 3 Æ P = 85 %ΔQ / %ΔP = +40% / ‐6% = ‐7 Discuss elasticity = ( ΔQ / ΔP )* P / Q = Slope * P / Q Intertemporal Choice – change endowment, change interest rate Suppose that we earn $100 this year and $50 next year and the interest rate = 10%. Plot the intertemporal budget constraint. If the interest rate rises to 20%, what happens to the person’s most desired bundle. Discuss the income and substitution effects. (Problem 5.10 and extension) Discuss present value: Present Value of X dollars in the future is X / (1 + i)t ‐‐ Reason – if we put X / (1 + i)t into the bank, it would be worth X dollars in year t. Discuss the intertemporal budget constraint. C0 + C1 / (1 + i)t = Y0 + Y1 / (1 + i)t Present value of consumption = Present value of income Multi‐year intertemporal budget constraint (T = year of expected death): t =T t =T Ct Yt = ∑ ∑ t t t =0 (1 + i ) t =0 (1 + i ) Permanent income hypothesis. (Wikipedia: The permanent income hypothesis was developed by the American economist Milton Friedman. In its simplest form, the permanent income hypothesis states that the choices consumers make regarding their consumption patterns are determined not by current income but by their longer‐term income expectations.) What implication does this have for Bush’s one‐time $300 tax rebates? Answer: should have very little effect on consumption and therefore have very little effect on stimulating the economy. Risk and uncertainty Risk = when the outcome of an activity is unknown (although the various outcomes and their probabilities are known). Expected Return = p1 * r1 + p2 * r2 + …= E(ri) Expected Utility = p1 * U(r1) + p2*U(r2) + … = E[U(ri)] Suppose that I could give you the following choice – Guaranteed B or 50% chance of C/A. Raise your hand if you would prefer guaranteed B, roll of dice, indifferent. Risk averse = would prefer $50 to 0.5*$0 + 0.5*100 U($50) > 0.5 * U($0) + 0.5*U($100) • Risk adverse = would prefer a certain amount ($X) over a risky amount with the same expected return ($X) • Risk loving = would prefer a a risky amount with the same expected return ($X) over a certain amount ($X) • Risk neutral – indifferent How much would a person pay for insurance? Discuss Figure 5.13 on page 148. Discuss Problem 5.16. Note: insurance is good for both purchaser and ins. co. – why? Expected Return = 50% * ($40) + 50% * (‐20) = $10. Actuarially fair premium = Expected loss Suppose 10% chance of accident that will cause $1000 damage, and a 90% chance of nothing happening. Actuarially fair insurance would cost you $100. Insurance companies will charge more than this to earn a profit. You are willing to buy if insurance premium <= risk premium. Lesson 6 -- Exchange Efficiency and Prices; Equity How much would a person pay for insurance? Discuss Figure 5.13 on page 148. Discuss Problem 5.16. Note: insurance is good for both purchaser and ins. co. – why? Expected Return = 50% * ($40) + 50% * (‐20) = $10. Actuarially fair premium = Expected loss Suppose 10% chance of accident that will cause $1000 damage, and a 90% chance of nothing happening. Actuarially fair insurance would cost you $100. Insurance companies will charge more than this to earn a profit. You are willing to buy if insurance premium <= risk premium. Exchange & Efficiency Goal: to show that a “competitive market” yields goods distribution that is Pareto efficient. Pareto efficiency/optimality = an allocation of goods such that there is no way to make any person better off without hurting anybody else. Pareto efficiency is a minimal criterion for a “good” economic condition. Edgeworth box – useful to study exchange between two people. Example 1 Suppose we have 2 people: Ted and Amy – they have endowments of Apples and Bread: Apples Bread Amy 4 7 Ted 8 3 Total 12 10 Draw Edgeworth box (Bread on the Y‐axis, Amy in the lower left), endowment, indifference curves, area of pareto improving trades (region of mutual advantage – draw to the NW). Note: assume that Ted and Amy only care about their consumption of Apples and Bread. Suppose that MRSa = 3, MRSt=1. Amy would be willing to give Ted 3 breads for 1 apple – Ted is willing to trade them at a rate of 1 to 1. Amy’s MRS of bread for apples is greater than Ted’s. That means Amy is more willing to lose some bread to get more apples than Ted – this facilitates a Pareto improving trade where Amy gets more apples and Ted gets more bread. Note: Anything outcome in this box is feasible – however, Amy and Ted are only willing to trade w/in this lens, as anything else lowers one of their utilities. What would be the terms of trade? Answer anything between 1 and 3 breads for 1 apple. Now, where will they trade? Show the contract curve. Note that the origins are always on the contract curve. What can we say about their marginal rates of substitutions along the contract curve? Now, suppose that there are many consumers rather than 2 – their aggregate demands and supplies of goods will determine an equilibrium price. At these given prices, MRS = Px / Py for all consumers – this means that every consumer will have the same MRS and we achieve Pareto efficiency. Efficiency First Theorem of Welfare Economics: Given a few assumptions, the equilibrium allocation of a many‐person exchange economy is Pareto‐optimal. Assumptions: 1) the market is competitive – i.e., all market participants take the prices as given by the market and no one participant can affect or set the price. Furthermore all consumers pay only one price. Lastly, consumers can buy all that they want at the given price (there are no large consumers). 2) There are no “externalities” to the consumption decision. An externality occurs when the welfare of one person is affected by the consumption decision of another person (e.g., driving and smog). This is Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand”. It would be very difficult for governments to allocate goods in a Pareto efficient manner without relying on markets. Creates strong incentives for laissez‐faire policies. Equity Second Theorem of Welfare Economics: Any Pareto‐efficient allocation can be achieved through the market given an appropriate assignment of endowments. Technical assumption: market participants have convex preferences. This theorem says that you can redistribute the original endowment and the market will take you to the desired equilibrium – problems of equity and efficiency can be handled separately. Taxes / subsidies cause a wedge between the price the buyer pays and the price the consumer receives. Thus, taxes / subsidies cause inefficiency because buyer and seller will not have the same MRS (because they face different price‐ratios). (i.e., decisions are ʺdistortedʺ by the change in the relative prices of goods) Taxation and redistribution should be based on endowments – NOT CHOICES. Discuss Minimum Wage, Food Stamps, Rent Control. Why do we do use these programs instead of lump‐sum redistribution? *********************** General Equilibrium – occurs when all markets are in equilibrium. Changes in one market affect all related markets. Example: Draw trucking and railroad industriesʹ markets. Suppose that we set a price floor in the trucking industry. This raises the price of trucking. What does it do to demand for rail service? Discuss the feedback effect. What other industries would be affected.