* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A deflationary wave has arrived in the Eurozone but it is not the next

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Nouriel Roubini wikipedia , lookup

Economic bubble wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Nominal rigidity wikipedia , lookup

Phillips curve wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

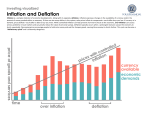

Macro Insight March 2015 A deflationary wave has arrived in the Eurozone but it is not the next Japan For professional clients and institutional investors only reasonable to distinguish between deflation due to some favourable external shock or supply-side development, such as the slump in oil prices, and a more general decline in the prices of goods and services due to weak demand. The former is sometimes described as ‘good’ deflation, which may simply increase the amount of money that people have to spend on other items. But even where falling prices are a symptom of weakness in domestic demand, sometimes described as ‘bad’ deflation, the resulting boost to real incomes may still mean that deflation is part of the cure. Summary Low oil prices drove Eurozone inflation into negative territory in December 2014 The current outlook for deflation is not necessarily dangerous, as it is mainly driven by the oil price drop, which only has a temporary impact on energy price inflation However, low core inflation could continue as wage growth will remain weak due to a large amount of slack in the labour market What is going on in the Eurozone and US? The ECB’s QE programme reduces headwinds to inflation through a weaker currency High levels of spare capacity across the developed world, in addition to deleveraging forces, have exerted downward pressure on global consumer prices. The recent tumble in commodity prices has exacerbated this trend. In the US and Eurozone, inflation has already dipped below zero while the UK, Japan and most of Asia are experiencing disinflationary trends. Accordingly, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England are likely to ‘look through’ a period of deflation and begin raising rates. However, a phase of falling headline consumer prices has opened the door for easing by over 30 central banks so far this year, particularly in emerging markets. By the end of 2015, we expect inflation to pick up in Europe as there is a positive base effect from the decline in the oil price in 2014 What is deflation and why is it so bad? Deflation in the Eurozone is a “protracted fall in prices across different commodities, sectors and countries. In other words, it is a generalised protracted fall in prices, with self-fulfilling expectations”. This is the definition of deflation that ECB President Mario Draghi gave in the summer of 2013. At the time, Draghi said that the Eurozone was just on a disinflationary trend (falling inflation rates), while risks of deflation (falling prices) were, however, subdued. Nearly two years later, inflation in the Eurozone has turned negative. This report looks at what forces are dragging down inflation, mainly in Europe, but also elsewhere. Is prolonged deflation a real threat for the Eurozone? It is worth highlighting that the Eurozone has been in deflation before. As Figure 1 shows, having remained remarkably steady and close to the ECB’s 2% ceiling in the first eight years of the euro’s life, inflation climbed sharply above 4% in 2008, before dropping equally sharply and entering negative territory in 2009. That bout of deflation lasted only five months, however, and inflation then rose quickly back to 3% before embarking on its latest long descent. Most consumers would, of course, regard falling prices as good news, given the boost to their spending power. After all, the burst of deflation in 2009 arguably contributed to the subsequent global recovery by boosting consumer spending. What’s more, it is 1 .Figure 1: Eurozone CPI, Core Inflation and ECB inflation target in February, as gasoline prices rose for the first time in eight months. However, with oil prices having declined again in recent weeks, there is a chance that inflation could dip into negative territory over the next couple of months if oil prices remain at current levels. However, this deflation is not necessarily something to worry about – it is ‘good deflation’. For a net importer of oil like the US, lower gasoline prices are a good thing. Moreover, with the real economy doing well, there is little danger that this temporary bout of falling energy prices will develop into a more insidious debt-deflation spiral. Furthermore, excluding food and energy prices, core consumer prices are well anchored and increased by a moderate 0.2% mom in February, pushing the annual rate of core inflation to 1.7% yoy. Admittedly, that is still below the Fed's 2% target, but it is currently being depressed by the indirect pass-through of lower energy prices and the stronger dollar. As those effects fade, core inflation should rebound to target early next year. Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 In December 2014, Eurozone inflation turned negative to -0.2% year-on-year (yoy) for the first time since October 2009, falling further in January (-0.6% yoy). However, latest figures show February’s headline inflation at -0.3% yoy. In line with the recent drop in oil prices, the main drag came from energy price inflation (-7.9% yoy). Core inflation (defined as headline excluding energy, food, alcohol & tobacco) was stable at 0.7% yoy in February. The breakdown showed that the decline in headline inflation was broad-based across the Eurozone, with 16 out of 19 countries reporting a negative inflation rate. Only Malta (+0.6% yoy), Italy (+0.1% yoy) and Austria (+0.5% yoy), listed a positive inflation rate. Furthermore, in the US there appears to be little risk of the current temporary bout of deflation becoming entrenched. Breakeven inflation rates have rebounded, as have inflation expectations. In addition, the faster pace of wage gains in the US coupled with sharply lower oil prices could underpin stronger consumer spending that should eventually lead to higher inflation. So in the US, deflation is less of a concern in our view, but a severe negative economic shock could trigger prolonged deflation. In the US, inflation has also been steadily falling and since its peak around mid-year 2014, headline CPI inflation has fallen from 2.1% to 0.8% on a year-on-year basis. PCE inflation has also plummeted, falling from 1.7% yoy to 0.8% yoy during this time. These sharp declines have been driven largely by a 50% drop in oil prices over the past year. Figure 3: US breakeven inflation rates and US inflation expectations Figure 2: US CPI and Core Inflation Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 The latest data shows that US consumer prices rose 0.2% month-on-month (0.0% yoy) in February, after technically falling into ‘deflation’ in January. The -0.7% mom (-0.1% yoy) decline in consumer prices in January was entirely due to a massive 18.7% mom plunge in gasoline prices but the drag from energy prices faded Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 2 Concerning trends in inflation in Asia . Figure 5: Main contributions to Eurozone inflation However, deflation risk is no longer an issue confined to the developed world. Within Asia ex-Japan, producer prices in China have been in deflation for the last 35 months. This has very quickly spread across the region with seven economies now experiencing deflation in producer prices for most of the past three years. We are also increasingly witnessing deflationary pressures spreading quickly to headline inflation. Figure 4: Eight out of 10 Asian ex Japan countries are in PPI deflation Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 With oil prices doubling in 2009, however, the negative impact on inflation quickly went into reverse and with core price pressures remaining more robust, the headline inflation rate rebounded sharply. Indeed, only 12 months after troughing at -0.6% in July 2009, inflation was back close to the ECB’s 2% ceiling and its subsequent further climb towards 3% even prompted the ECB to raise interest rates twice in 2011. Of course, falling oil and energy prices have also played an important part in the latest drop in inflation and it is worth noting that core and food price inflation are low from a historical perspective. During the summer of 2014, food price inflation turned negative for the first time since the financial crisis, while core inflation has balanced around its new historical low of 0.6% since September. Source: CEIC, Jan-15 data for China, India, Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. Sept-14 data for Hong Kong and Dec-14 data for the other countries. In many emerging Asian economies, last year’s collapse in oil prices is still feeding through into lower inflation but, for the vast majority, the risk of a prolonged period of deflation is low in our view. In most cases deflation is unlikely to become ingrained because income growth is rapid in Asia and there is scope to loosen monetary policy further. Another reason why deflation is likely to be short-lived is that these countries’ currencies have generally weakened since the start of the year. This should partly offset the impact of lower energy prices on inflation rates. Deflationary pressures are now broader Although energy effects have been the primary downward force, deflationary pressures are generally broader than they were back in 2009. Not only is core inflation lower than it was then (+0.7% versus a low of +0.8%) but more components of the CPI have entered negative territory. Key components such as household goods, communication, and recreation & culture all have low or negative inflation. Figure 6: Eurozone inflation by key sectors - June 2009 and December 2014. What has caused the fall in Eurozone inflation and will the latest bout of deflation be just as brief as the last one? A key issue here is what has caused the fall in Eurozone inflation. The chart below sheds light on this by showing the contributions to annual inflation of the three key components that are energy, food, and core. It shows that the 2009 bout of deflation was very strongly driven by a deeply negative contribution from energy prices, reflecting the sharp drop in oil prices from over USD 130 per barrel in mid-2008 to just USD40 per barrel by the end of that year. Source: Eurostat, as of March 2015 3 Inflation expectations have fallen markedly which could give rise to prolonged deflation Figure 8: Falling prices make debt burdens harder to service Another rather less comforting development is the fact that the drop in inflation appears to have caused inflation expectations to become distinctly detached from the ECB’s 2% target. For example, as the chart below shows, the implied market expectations for consumer price inflation has fallen markedly over the past year. Figure 7: Eurozone Inflation Expectations Source: Bloomberg, as of March 2015 2. The second risk is that a surge in debt defaults drives asset prices lower, particularly property and other assets used as collateral, further increasing the fragility of the financial system. This in turn, could lead to an even more catastrophic decline in economic demand. Admittedly, the chart shows that the same measure dropped equally sharply back in 2009, only to rebound just as quickly when inflation itself picked up again. But if deflation lasts longer this time – if only because energy effects are not so quickly reversed – it will create a risk of prolonged deflation, where the danger of a more permanent shift in inflation expectations could feed back into lower wage growth and a delay in consumer spending could presumably increase. 3. The third risk is that expectations of ever-falling prices become entrenched and a debt-deflation spiral develops. This could encourage households to delay spending, in the hope that they will eventually be able to buy goods more cheaply. It could also prompt companies to cut back on investments, for fear that future returns will be lower. This sort of deflationary spiral was avoided in 2009 partly because major central banks responded with bold monetary easing to boost inflation expectations and keep real interest rates positive. But with nominal interest rates now near zero, they have much less room for manoeuvre. What are the risks of prolonged deflation in Eurozone? Who is most at risk in a prolonged Eurozone deflationary environment? If there is a severe negative economic shock, the risk of prolonged deflation in the Eurozone could rise, and past experiences of deflation suggest prolonged deflation may significantly harm economic activity. Not all Eurozone countries are expected to face the same issues in a prolonged deflationary environment. Heavily-indebted economies with high unemployment, low-trend real growth and already low expectations of inflation are particularly vulnerable to deflationary spirals, as well as countries that have a large output gap. To create a list of the countries most likely to be impacted, the IMF in its World Economic Outlook October 2014 publication selected the Eurozone countries that have a budget deficit larger than 3.0%. The forecast output gap in 2014 for those countries was also noted. The IMF then ranked the countries for both variables, and added the two results to rank the countries again, based on this combined score. That final ranking was thus based on an unweighted average of the other two ranked scores. Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 There are three potential risks if deflation becomes entrenched: 1.The cost of servicing existing debt rises as inflation falls. Falling inflation leads to higher real interest rates as nominal rates are often fixed. So rather than simply boosting spending power, falling prices may lead to outright declines in nominal incomes – including wages, profits and government revenues. This means that the current low rates of inflation in the Eurozone are increasing member countries’ already high public and private debt levels. Rising debt-service costs may in turn reduce consumer spending and business investment. 4 Lessons from Japan Those most susceptible to lowering prices were generally the peripheral countries that are currently working to recover from the crisis and to regain competitiveness respective to core countries, as shown in Table 1. But one of the core countries, France, also made the list. Taking into account the weak economic growth in France and Italy over the first half of 2014, these two are especially likely to face further disinflationary pressure. Japan’s case was characterised by a series of negative and mutually reinforcing factors, some of which are shared by the Eurozone. At the end of the 1980s, Japan saw an asset price bubble, prompting the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to step in with sharp monetary tightening. This caused the stock market to crash, asset prices to plummet and the economy to fall into recession. Consequently, non-performing loans increased dramatically and credit became extremely constrained. In the absence of an expansionary monetary policy from the Bank of Japan, deflation set in a couple of years after the crash. Figure 9: Vulnerability rankings Overall Country Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Spain Portugal Cyprus Greece Italy France Ireland Slovenia Fiscal balance Output gap 2014 (% of 2014 (% of GDP) GDP) -5.7 -5.0 -9.2 -3.5 -5.0 -3.4 -3.6 -9.4 -3.3 -4.3 -4.0 -2.8 -4.7 -2.5 -4.0 -3.3 This shows just how harmful entrenched deflation can be for the economy. Following the bubble’s burst, Japanese corporations held high levels of debt, which remained the same in nominal terms. Then, as prices fell, the real value of corporate debt increased. To avoid further increases in debt, these firms reduced investment which in turn lowered growth, deepening the economic downturn, increasing unemployment and widening the output gap. Japan’s greatest weakness was the policy response to its economic woes, including unsuccessful experiments in quantitative easing. Source: IMF data, World Economic Outlook as at October 2014 Deflation is rare Persistent deflation, with prices falling over many years, is an exceedingly rare phenomenon, at least in the postWorld War II era. There have been only 14 occurrences of deflation in the past 54 years, of which only three (including Japan) occurred in developed economies. With the exception of Japan – which has had two separate periods of deflation since the late 1990s – all of the remaining examples of deflation were in countries operating fixed exchange-rate regimes Japan is still suffering from effects of the ’Lost Two Decades’. Economic indicators finally seem to be returning to healthier levels as Abenomics sets in, with its ’three-arrowed’ reform programme (fiscal stimulus, monetary easing and structural reform) to address chronically low inflation, decreasing worker productivity, and an ageing population. However, the implementation of structural reform has been delayed. There are some similarities in the causes of deflation in Japan and the recent experience in parts of Europe. Like Spain and Ireland, Japan saw a significant property bubble that, when it burst, threw the economy into recession. However there has not been a Europe-wide property bubble. Like Japan, European banks were slow to write off bad loans, and credit growth has stagnated. Figure 10: Deflation is unusual in advanced economies DM Hong Kong Japan (x2) Malta EM Argentina Bahrain (x2) Libya (x2) Niger Saudi Arabia (x2) Senegal Syria However, in Europe the stock market bubble was not as large and its bursting was part of an international phenomenon in the wake of the Lehman collapse. Furthermore, in the absence of exchange rate devaluations, crisis-hit countries reacted with a raft of reforms to regain competitiveness, including wage and price moderation and, where possible, a shift from labour taxes to consumption taxes. This socalled “internal devaluation” aims to depreciate the real effective exchange rate by realigning labour costs with productivity, thereby restoring competitiveness and, as a result, unwinding current account deficits, a Source: OECD and IMF. Deflation definition: 3years or more of negative inflation Sample 1960-2013 (54 years), 180 countries, annual CPI inflation 5 first step toward a sustainable growth path for these economies. This is also supported by our own Core Inflation Leading indicator model (based on the output gap, trade weighted euro and a survey measure of inflation expectations), which expects core inflation to remain stable. If that is the case, deflation will remain an energy-driven and relatively short-lived phenomenon. Countries in which the internal devaluation has been the most successful are generally those where structural reforms have also been readily implemented such as Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and, to some extent, Greece. By contrast, France and Italy have fallen behind in the reform race. Indeed, it could readily be classified as “good deflation” insofar as it will boost private consumption through higher real wage growth and could therefore help to revive the Eurozone’s flagging economic recovery. Added to this, low core inflation primarily reflects low inflation in non-energy industrial goods, while service price inflation, which is highly dependent on labour as an input and closely related to wage growth, has remained relatively stable. Overall, the fact that Japan is the only relevant (modern) example provides some reassurance that deflation is not something that occurs easily or frequently in developed countries. Figure 11: Japan CPI and Core CPI inflation Figure 13: Eurozone core goods and services Inflation Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 What about core Eurozone inflation? Where will core inflation go? Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 Spare capacity has also exerted downward pressure on core inflation Just how deep deflation becomes and how long it lasts will depend most importantly on the behaviour of core inflation. A quick look at the past behaviour of core inflation would appear to provide some reassurance. As the chart below shows, it has tended, not surprisingly, to be more stable than the headline rate, fluctuating in a much narrower band and at a record low of -0.6% yoy in January 2015; it is already at the bottom of that band. High levels of spare capacity have also exerted downward pressure on consumer prices in the Eurozone. Eurozone core inflation (the ECB has little control over food and energy prices) is highly correlated with the output gap, which is the difference between how much an economy is producing and how much the economy could produce. A lot of spare capacity in factories or a lot of unemployed workers discourages firms from raising prices because their competitors can use their idle capacity or labour to produce more and undercut them. The output gap is notoriously hard to measure but an expanding output gap has usually pushed core inflation down, and a narrowing output gap has pushed core inflation up. Therefore, to avoid a prolonged period of deflation, the output gap needs to close and GDP growth to pick up. Based on estimates from the OECD, the Eurozone’s output gap was quite large at -3.3% in 2014, which means that core inflation could pick up if the ECB’s QE programme succeeds in boosting growth and closing the output gap. Figure 12: Eurozone CPI and Core Inflation, ECB target Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 This might suggest that the general stickiness of prices in the Eurozone will prevent core inflation from falling any further over the coming months. 6 lower end of expectations. No French or German banks were required to source more capital. Figure 14: Output gap and 12 month change in core CPI inflation How can low inflation be addressed? The tricky part is determining how to fight low inflation and avoid prolonged deflation. With interest rates already close to zero, standard monetary policy virtually ceases to be effective. Over the last months, the ECB has tried hard to ease financial conditions, using various non-standard monetary policy measures, such as providing ultra-cheap loans targeted to those banks that lend to small and medium-sized enterprises, and purchasing private sector assets (covered bonds and asset backed securities). Source: Bloomberg, as of March 2015 Finally, as an antidote to deflation, the European Central Bank (ECB) rolled out its aggressive QE program in March 2015. The package includes injecting EUR 1.1 trillion through the purchases of government bonds and private sector assets, worth EUR60 billion a month, until at least the end of September 2016 or when the inflation rate shows signs of improvement towards its target. But QE in the Eurozone has arrived late. The US is winding down the QE programme it embarked on 6 years ago when low inflation rates first started to raise alarm. Wage pressures have been subdued in the Eurozone. While Eurozone unemployment remains high, the fact that the unemployment rate has stopped rising and even fallen modestly over the last year suggests wages could soon start to pick up from recent very low levels, with corresponding potential upward effects on headline inflation. Even a quick look at the Eurozone’s monetary dynamics might suggest that disinflationary pressure may soon ease. The chart below shows the relationship between broad (M3) money growth and CPI inflation with the recent pick-up in M3 growth pointing to rising inflation ahead. Furthermore, this might become clearer if the ECB’s quantitative easing (QE) programme results in a further pick-up in money supply growth. The ECB’s QE programme reduces headwinds to inflation The ECB’s QE programme is expected to lift inflation through various channels. Figure 15: Eurozone inflation and M3 The first channel is the currency. On a tradeweighted basis, the euro depreciated significantly in 2014 (-6.0%) and this decline has accelerated since the beginning 2015 (an additional 7.6%), following the ECB’s announcement that it would purchase sovereign bonds and increase its balance sheet further. Euro depreciation should put upward pressure on inflation. The lower exchange rate has already raised manufactured import prices in H2 2014 by 1.9%, according to Eurostat, and these are expected to increase further in Q1 2015. This increase alone should help lift core goods price inflation in the first half of the year. The weaker EUR also will lift food-price inflation this quarter and dampen the impact of lower oil prices. Source: Bloomberg, as of 24 March 2015 Other factors also suggest that the Eurozone could avoid a prolonged downward slide into deflation. For instance Eurozone business and consumer confidence has picked up since the dip in September while household savings as a proportion of gross disposable income has continued to edge lower since the start of the year, suggesting that spending could be set to rise in the coming months and boost aggregate demand. The largest Eurozone banks also appear to be in better shape than expected, with capital shortfalls identified by the ECB’s latest asset quality review coming in at the The second channel at play is inflation expectations. The ECB’s QE programme should support inflation expectations as it signals the ECB is committed to its mandate of maintaining price stability. Hence, the current monetary easing should support wage growth if the stimuli convinces wage earners that they should expect 2% inflation. Related to this, easing should limit second-round effects and the risk of a dangerous kind of deflation, where wages follow inflation lower. 7 as they did in 2009/10, then it is likely that headline inflation will also rise again quickly and the current burst of deflation might prove to be just as brief as the last one. Even if the oil price does not increase but remains at its current level, headline inflation should turn positive towards the end of this year. However, the price dynamics will continue to be limited by a large negative output gap, high unemployment and the absence of wage pressures. Furthermore, with Eurozone inflation already in negative territory, investors could remain sensitive to any negative exogenous shocks, for example from Greece or from the situation in Ukraine and Russia, that may put further pressure on the outlook for inflation and growth. The last channel is the growth outlook. The ECB expects GDP to grow by 1.5% in 2015 (up from 1% in the December projections), 1.9% in 2016 (up from 1.5%) and 2.1% in 2017, and QE poses upside risks to this view. Investment Implications The obvious question is: will QE make a difference, especially as government bond yields in Europe are already so low? There is certainly scope for bond yields in peripheral Europe to fall further, and for those lower interest rates to feed through to the real economy via the banking system. However, we feel that ECB’s QE programme will eventually benefit the Eurozone economy by reducing the risk of prolonged deflation and that the main impact will come through from the weaker euro. This should make European exporters more competitive internationally and provide a boost to GDP and corporate earnings growth, and therefore be a positive for risk assets such as European equities. Our long-term investment views have not changed; we continue to favour most riskier assets, such as equities, over perceived safe-haven developed market government bonds. The ECB QE programme supports the view that the world’s major developed market central banks are ready and willing to provide monetary stimulus if necessary to support their economies and to ward off entrenched deflation. Looking ahead, we expect oil prices to eventually increase from current very low levels. We are not there yet, but if they rebound eventually over the coming year Rabia Bhopal Macro & Investment Strategist Macro and Investment Strategy team Michael Hampden-Turner Senior Macro & Investment Strategist Julien Seetharamdoo Chief Investment Strategist Michael Hampden-Turner is a Senior Macro and Investment Strategist based in London having recently joined HSBC Asset Management in December 2014. He previously held global macro, asset allocation, fixed income and credit strategy roles at Citigroup and RBS over a twenty year career both as a publishing top down strategist and a desk analyst. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge and Harvard University. Julien Seetharamdoo is Chief Investment Strategist within HSBC Global Asset Management’s Macro and Investment Strategy team where he provides analysis and research on the key issues facing the global economy and asset markets. Prior to joining HSBC, Julien has worked for Coutts & Co, RBS and Capital Economics. He holds a first-class degree in Economics from Cambridge University and a PhD in Economics from the Management School, Lancaster University focusing on the implications of the European Monetary Union. Rabia Bhopal Macro & Investment Strategist Renee Chen Senior Macro & Investment Strategist Rabia Bhopal is a Macro and Investment Strategist and provides analysis and research on the key issues facing the global economy and asset markets, with particular focus on Frontier Markets. Rabia has been working in the industry since 2003. Prior to joining HSBC in 2012, Rabia held Economist roles at Standard & Poor¹s, Lloyds TSB Corporate Markets, Financial Services Authority and the Economist Intelligence Unit. She holds a degree in Economics from Brunel University in London. Renee Chen joined HSBC Global Asset Management as Macro and Investment Strategist in April 2012. Prior to this role, she held Economist roles at Macquarie Capital Securities, Nomura and Citigroup and has over 14 years’ experience in economic and policy research. Renee holds a master’s degree in International Affairs and Economic Policy Management from Columbia University, New York and an MBA in Finance and Investment from George Washington University, Washington DC. Shaan Raithatha Macro & Investment Strategist Herve Lievore Senior Macro & Investment Strategist Hervé Lievore is a Senior Macro and Investment Strategist based in Hong Kong. Before joining HSBC, he spent five years at AXA Investment Managers in London and Hong Kong as an economist and strategist, covering Asia and commodities. He was also involved in the firm’s tactical asset allocation committees. He started his career 18 years ago at Natixis in Paris, where he mostly covered Asian markets. 8 Shaan is a Junior Macro and Investment Strategist within HSBC Global Asset Management’s Macro and Investment Strategy team. Prior to this role, he spent 18 months on the HSBC Global Asset Management Graduate Programme working as an analyst on both the Global Emerging Markets Equity and Equity Quantitative Research teams. Shaan holds a bachelor of arts degree in economics from the University of Cambridge. Important Information: For Professional Clients and intermediaries within all countries except Canada and for Professional Investors within Canada. This document should not be distributed to or relied upon by Retail clients/investors. The contents of this document may not be reproduced or further distributed to any person or entity, whether in whole or in part, for any purpose. All non-authorised reproduction or use of this document will be the responsibility of the user and may lead to legal proceedings. The material contained in this document is for general information purposes only and does not constitute advice or a recommendation to buy or sell investments. Some of the statements contained in this document may be considered forward looking statements which provide current expectations or forecasts of future events. Such forward looking statements are not guarantees of future performance or events and involve risks and uncertainties. Actual results may differ materially from those described in such forward-looking statements as a result of various factors. We do not undertake any obligation to update the forward-looking statements contained herein, or to update the reasons why actual results could differ from those projected in the forward-looking statements. This document has no contractual value and is not by any means intended as a solicitation, nor a recommendation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument in any jurisdiction in which such an offer is not lawful. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of HSBC Global Asset Management Macro & Investment Strategy Unit at the time of preparation, and are subject to change at any time. These views may not necessarily indicate current portfolios' composition. Individual portfolios managed by HSBC Global Asset Management primarily reflect individual clients' objectives, risk preferences, time horizon, and market liquidity. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. Past performance contained in this document is not a reliable indicator of future performance whilst any forecasts, projections and simulations contained herein should not be relied upon as an indication of future results. Where overseas investments are held the rate of currency exchange may cause the value of such investments to go down as well as up. Investments in emerging markets are by their nature higher risk and potentially more volatile than those inherent in some established markets. Economies in Emerging Markets generally are heavily dependent upon international trade and, accordingly, have been and may continue to be affected adversely by trade barriers, exchange controls, managed adjustments in relative currency values and other protectionist measures imposed or negotiated by the countries with which they trade. These economies also have been and may continue to be affected adversely by economic conditions in the countries in which they trade. Mutual fund investments are subject to market risks, read all scheme related documents carefully. We accept no responsibility for the accuracy and/or completeness of any third party information obtained from sources we believe to be reliable but which have not been independently verified. HSBC Global Asset Management is the brand name for the asset management business of HSBC Group. The above communication is distributed by the following entities: in the UK by HSBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, who are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority; in Jersey by HSBC Global Asset Management (International) Limited which is regulated by the Jersey Financial Services Commission for Fund Services & Investment Business and is licensed by the Guernsey Financial Services Commission for Collective Investments & Investment Business. HSBC Global Asset Management (International) Limited is registered in Jersey under registration number 29656 with its registered office at HSBC House, Esplanade, St Helier, Jersey JE4 8WP. HSBC Bank plc acts as settlement agent to HSBC Global Asset Management (International) Limited. Approved for issue in France by HSBC Global Asset Management (France), a Portfolio Management Company authorised by the French regulatory authority AMF (no. GP99026); in Germany by HSBC Global Asset Management (Deutschland) which is regulated by BaFin; in Switzerland by HSBC Global Asset Management (Switzerland) Ltd; in Hong Kong by HSBC Global Asset Management (Hong Kong) Limited, which is regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission; in Canada by HSBC Global Asset Management (Canada) Limited which is registered in all provinces of Canada except Prince Edward Island; in Malta by HSBC Global Asset Management (Malta) Limited, which is licensed to provide investment services in Malta by the Malta Financial Services Authority; in Bermuda by HSBC Global Asset Management (Bermuda) Limited, of 6 Front Street, Hamilton, Bermuda which is licensed to conduct investment business by the Bermuda Monetary Authority; in India by HSBC Asset Management (India) Pvt Ltd. which is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India; in United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Lebanon by HSBC Bank Middle East Limited which is regulated by Jersey Financial Services Commission and Central Bank of United Arab Emirates; in Oman by HSBC Bank Oman S.A.O.G Regulated by Central Bank of Oman and Capital Market Authority, Oman; in Latin America by HSBC Global Asset Management Latin America. and in Singapore by HSBC Global Asset Management (Singapore) Limited, which is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. HSBC Global Asset Management (Singapore) Limited, or its ultimate and intermediate holding companies, subsidiaries, affiliates, clients, directors and/or staff may, at anytime, have a position in the markets referred herein, and may buy or sell securities, currencies, or any other financial instruments in such markets. HSBC Global Asset Management (Singapore) Limited is a Capital Market Services Licence Holder for Fund Management. HSBC Global Asset Management (Singapore) Limited is also an Exempt Financial Adviser and has been granted specific exemption under Regulation 36 of the Financial Advisers Regulation from complying with Sections 25 to 29, 32, 34 and 36 of the Financial Advisers Act). Copyright © HSBC Global Asset Management Limited 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, on any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of HSBC Global Asset Management Limited. FP15-0557 (expiry date: 26/03/2016) 9