* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download International political economy exam, january 2016

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

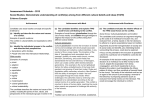

INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY EXAM, JANUARY 2016 2. Globalisation has not entailed any significant changes in the role of the state in the international political economy. Critically discuss this assertion. Rasmus Grand Berthelsen 140993-1827 B.Sc. International Business and Politics Copenhagen Business School, 2016 STU count: 22,483 (9.8 standard pages) “Globalisation has not entailed any significant changes in the role of the state in the international political economy. Critically discuss this assertion,” Introduction There is hardly doubt that globalisation has influenced how states operate. Throughout the end of the twentieth century and up until now, the changing role of states in determining the outcomes of the global political economy has been a recurrent topic of interest. This paper will critically discuss the statement that globalisation has not entailed any significant changes in the role of the state in the international political economy. It will do so by examining key actors in the global political economy after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, through the lens of especially neoGramscian approaches occasionally contrasted to neo-realist theory, and drawing upon recent empirical developments. The paper argues that globalisation has led to a coalition between the interests of a new transnational financial hegemon and the ruling classes of states, which has changed the role of the state into being subordinate to the ideas of this new hegemon. Whereas before the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, states possessed the hegemonic capacity, globalisation has played a key role in establishing new social relations, effectively making the use of coercive state power obsolete. This argument is developed by first defining how this paper perceives globalization, the state, and within which timeframe it operates, as these concepts are crucial for establishing a frame of reference. This is followed by an examination of the Bretton Woods institutions and their role in the globalisation process in a neo-Gramscian perspective, opposed to a neo-realist one. Here, the paper argues that the ideas of the IMF and the World Bank has been key in shaping states’ interests, and developed a consensus across the global political economy, which has made states buy in to having subordinate positions. The argument is further developed by investigating the 2008 global financial crisis, where the globalisation process of increased commodification and capital movement created a financial hegemon, which constrained the role of the state in determining the outcome of the crisis. Moreover, by examining the contemporary offshore world, it is argued that since states are now subordinate to a transnational financial hegemon, they are constrained in their use of coercive state power to pursue their original purpose due to the dominance of international capital over national capital. A definition of globalisation and its scope is an analytical imperative for this assignment. First of all, the continuing increase in global trade and cross-border financial transactions constitute main 1 components of this phenomenon, as well as the commodification of capitalist social relations (Wigan, 2015a). Since national economic policies undertaken must consider the effects of the surrounding global economy, integration of national economies has led to the dominance of international capital over national capital. For the purpose of this assignment, globalisation is thus defined as a process of increasing capital mobility and commodification leading to the dominance of international capital. Another analytical imperative is a definition of the state. For the purpose of this assignment, the state will be defined more precise than just an entity that secures property right, but one that also carries an organizational and facilitating role resulting from an original purpose to exercise control over its own territory and provide stability and security for its citizens. Finally, in order to assess whether the role of the state has changed, this paper takes a point of departure in a global political economy just before the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, where the role of the state were undisputed as the most powerful actor in determining who gets what, when and how. Establishing a transnational financial hegemon The end of the Bretton Woods system led to global finance replacing publicly managed order. Within the impossible trinity (The Mundell-Fleming Thesis of 1962), the Bretton Woods system allowed fixed exchange rates (to the dollar, which was fixed at $35/ounce) and monetary policy autonomy (central banks could manipulate money supply), but this meant that European countries and Japan imposed capital controls in order to tame speculation (Wigan, 2015b). However, after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 (effectively 1975), states went into negotiations with the IMF over what should replace the gold-dollar standard, and floating exchange rates were adopted. This meant that capital mobility was highly possible, and monetary policy autonomy were preserved – although it was weaker, since governments now had to operate indirectly through exchange rates. The IMF was initially established as a stabilisation fund, but within the new international monetary system, it was granted the role of overseeing exchange rate policies of members (Wigan, 2015b). Moreover, the World Bank, initially established to provide support for post-conflict reconstruction through promotion of free trade and private investment, also played a key role. Within this framework, the ideological coalition of Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s, the so-called Washington Consensus, pushed for deregulation and liberalisation of capital markets through institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank. These are seen as forerunners of globalisation, economic integration and economic liberalism (Broome, 2014), which resulted in a financialisation of the international economy. As an example, according to McKinsey Global Institute, in 1980 global GDP was $10.1 trillion, and financial assets were $12 trillion. In 2006, 2 global GDP was $48.3 trillion, but financial assets had risen to $167 trillion (Wigan, 2015b).Taking into account the role of these institutions and the Washington Consensus it becomes clear that global finance has replaced the state-managed Bretton Woods-order. The international institutions established during the Bretton Woods era remains key in determining the outcomes of the global political economy. These institutions might have reflected the power relations when they were created, but they tend to encourage the reproduction of collective ideas (Cox, 1981). Here, Overbeek (2013) delivers a very thoughtful inside drawing on Stephen Gill’s work on internationalisation of authority: The collapse of the Soviet Union introduced the expansion of global transnational capital, leading economic policy to reflect the new power of investors. The OECD, the IMF, the World Bank the WTO, etc. were “engaged in the legal and political reproduction of this disciplinary neo-liberalism and ensure[d] through a variety of regulatory, surveillance and policing mechanisms that neo-liberal reforms [were] locked in” (Overbeek 2013, p. 172, emphasis original). Hence, these hegemonic ideas provide a coalition of interests in following the agenda of the Washington Consensus. The neo-realist approach would oppose this statement by claiming that since international institutions in this view are simply arenas for states to promote their own pre-given interests, the United States and the UK purposively created a liberal international economy through these institutions to promote their own interests (Gilpin, 2001). However, this paper does not see hegemony as a relationship between states, but rather as a form of class rule. Thus, the ideas of the Bretton Woods institutions (especially the IMF and the World Bank) are important in forming actors’ interests in the global political economy. The hegemonic role of the IMF and the World Bank has facilitated the coalitions of interests between the ruling classes of states and the transnational financial hegemon. Following the globalisation process after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, there has been an increasing commodification and dominance of international capital over national capital. This has led the social relations of production to become international, and on top of this structure is what Robert Cox (1981) calls the “transnational managerial class”. However, since finance capital now, for instance in the US, creates more corporate profits than manufacturing (Wigan, 2015a), this paper operates with what it terms the transnational financial hegemon. Opposing that “states, and other powerful actors as well, use their power to influence economic activities to maximize their own economic and political interests.” (Gilpin, 2001, p. 102), this paper operates with the hegemonic concept as founded not only upon the regulation of conflict between states, but also upon what powerful actors perceive as a global civil society (Cox, 1981). In this sense, the ideas of 3 the Bretton Woods institutions played a key role in determining the interests of the ruling classes of states, and hence they have developed a consensus across the global political economy, which makes states buy in to having subordinate positions. Here, Antonio Gramsci’s assertion of ideas constituting a factor in developing a transnational ruling class presents a very qualified insight. Starting from Marxist theories of the economic base (the social relations of production) determining the superstructure (culture and civil society), Gramsci modifies the deterministic relationship between the economic base and the superstructure into a coconstitutive relationship, since he sees the superstructure as having an independent causal effect (Wigan, 2015d). Classical Marxism accepts that the superstructure presuppose capitalism, but is otherwise not concerned with ideology (Overbeek, 2013). Here, the neo-Gramscian approach emphasises that social relations and institutions are constantly reproducing and legitimising the ideas of the existing hegemony. In this sense, there is not only a struggle between interests, but also a struggle between social forces promoting particular sets of ideas in the global political economy. With the change of the economic base into a commodification of capitalist social relations following globalisation (as defined above), the superstructure has changed. As this paper argues, the establishment of the IMF and the World Bank in an increasingly global political economy has changed the role of the state from being the dominant actor in the global political economy to being subordinate to the ideas of the new transnational financial hegemon. As the role of states in the global political economy becomes subordinate to the ideas of the transnational financial hegemon, states consent to a defining aspect of globalisation: capital mobility. This feature has enabled the global capitalist class to expand into the international realm, constituting a major actor in shaping the outcomes of who gets what, when and how in the global political economy. The fact that governments had less interventionist economic tools following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system and the following process of globalisation and financial market deregulation, has made them unable to influence the size and scope of capital in- and outflows from the domestic economy (Broome, 2014). This constraint is key to understanding the changing role of the state. In the following section, this paper will draw on the empirical events of the 2008 financial crisis and the contemporary settings of the offshore world in order to show how the transnational financial hegemon has changed the role of the state in the international political economy. 4 The global financial crisis The extensiveness of the global financial crisis of 2008 was a result of the globalisation process. The subprime mortgage bubble in the United States combined with the use of financial engineering to create asset-backed securities such as collateralised debt obligations (CDO’s), which were then pooled in order to reduce the risk of default into asset-backed securities sold to investors (Broome, 2014) were key drivers in triggering the global financial crisis. Banks all over the world acted as both borrowers and lenders in the mortgage market, and in a world where finance capital is massively bigger than global GDP, the logic of what extra credit does in the world economy becomes blurred. When the artificially high property prices in the United States began to fall, investors struggled to sell their CDO’s, and credit rating agencies downgraded the ratings of these at the same time, worsening the effect. This led to a liquidity crisis in the financial markets, and even though the ECB injected €95 billion and the Fed injected $24 billion into credit markets (Broome, 2014, p. 190), on September 15, the US investment bank Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. This was the trigger that turned the liquidity crisis into a global financial crisis due to the dominance of international capital over national capital. The global financial crisis shows that globalisation in the form of commodification of every aspect of human life (including risks) in combination with increasing capital mobility led to severe damages to the states, which they themselves could do little to prevent. The ideas of the transnational financial hegemon permeated the global political economy to an extend that constrained the role of the state in determining the outcome of the global financial crisis. The originate-to-distribute model of borrowing in global banking constitutes a key feature here. Following the revisions of Basel I in 1996 to incorporate market risks, the regulation of global banking became a matter of private risk management, and the creditworthiness of borrowers were no longer among the core strengths of major banks. This meant that the real risks carried by banks became obscure, since risky assets escaped regulation (Wigan, 2010). Following Basel II in 1999, large and sophisticated banks were able to transfer credit risks through e.g. credit default swaps (CDS), while credit rating agencies were given the role of guaranteeing market integrity and verifying financial innovations (Wigan, 2010). The combination of banks pooling mortgages into CDO’s and the incentives for credit rating agencies to rate these AAA, was a major factor in destabilising the international economy leading to the global financial crisis. If the states signing Basel I and II really knew, that they were giving up so much control of the financial markets, why did they do it? The answer is best found by looking at the coalition of interests between the global 5 financial hegemon and the ruling class of the state. Alan Greenspan (then Chairman of the Fed) stated in 2003: “Financial innovation will slow as we approach a world in which financial markets are complete in the sense that all financial risks can be efficiently transferred to those most willing to bear them” (quoted in Wigan, 2015d). Here, it becomes clear that the ideas of the transnational financial hegemon has influenced state interests to conform into a subordinate role in the international political economy. The subordinate role of the state becomes clear when looking at the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The embeddedness of large financial institutions in the global political economy combined with the enormous risks, which were no longer systematically linked to responsibility (Wigan, 2015c), left states forced to accept the innovations of financial engineering. In this sense, states gave so much power to the financial sector, allowing it to build up an unstable situation of fragile derivatives, without having the ability to control the outcome. Ultimately, the organizational and facilitating role still belongs to the state, why the responsibility of preventing total chaos in the global economy fell upon the states. Governments around the world quickly responded through a mix of monetary activism, fiscal stimulus and not least recapitalisation of banks. By injecting liquidity into the financial system through recapitalising distressed financial institutions, governments effectively became major stakeholders in these (Broome, 2014). The IMF also plays a key role in managing the crisis, since it has coordinated sovereign bailout loans in exchange for the implementation of certain policies. The world has seen the ruling class of states deciding to insure the financial system by pouring endless amounts of money into maintaining it. The bailout programmes undertaken by states underlines the reproduction of the transnational financial hegemon, following the change of the role of the state in the global political economy. The offshore world Another effect of globalisation in terms of increasing capital mobility is the offshore world. This term encompasses a combination of juridico-political phenomena within lightly regulated sovereign states (Palan, 2003). The term was first used to describe the Euromarket set up by the British after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in order to attract international financial activity. Essentially, the Euromarket is an offshore arrangement, which is enabled and constrained by the principles of sovereignty, and the most important of these financial centres is London. Although the British government acted out of pure interests of attracting capital when they purposively created this offshore arrangement, “as time has passed and the Euromarket has grown in size and complexity, attempts to re-regulate it have become increasingly dangerous as they risk disrupting 6 the entire financial system” (Palan, 2003, p. 32). Moreover, as the United States tried to re-regulate the Euromarkets in 1979 and failed, the U.S. Treasury came to the conclusion that the United States would gain more by encouraging its own offshore centres (such as international banking facilities in New York), instead of fighting other offshore centres (Palan, 2003). These actions show how globalisation in the form of increased capital mobility has facilitated the emergence of offshore finance, an important element of the social formation of the transnational financial hegemon. States are now subordinate to the ideas of the transnational financial hegemon, and therefore they have to compete in order to attract capital. The establishment of an offshore world following the merging of interests between the ruling classes of the states and the financial hegemon (as with the creation of the offshore centre in London) has reached such a capacity that states are no longer able to constrain offshore markets, since this carries obvious consequences (Palan, 2003). Instead, due to the dominance of international capital over national capital resulting from globalisation, states are caught in a race to the bottom of providing low taxes, few regulations and favourable business environments to global corporations. From a neo-realist perspective, it might be argued that states here acts as rational egoists and voluntarily chooses not to regulate, in order to maximise their own gains, as long as this is in their interest. However, this interest is only constituted due to the states themselves reproducing the ideas of the transnational financial hegemon. As defined earlier, the state carries an organizational and facilitating role, which requires it to collect taxes rather than paving the way for corporations to avoid these. Hence, the ideas of the financial hegemon has constrained state interests into competing with others in attracting capital instead of serving its main organizational and facilitating purpose. Taking these mechanisms to the extreme, we reach the creation of tax havens. Tax havens are sovereign states almost exclusively operating with the purpose of attracting international capital. They are often small islands like the Cayman Islands or Bermuda, and normally follow provisions of secrecy regarding banking, commercial and professional activity; few restrictions regarding financial transactions; and political and economic stability (Palan, 2003). At the end of 2000, banks in the Cayman Islands had $782 billion worth of external assets, holding more than both Swiss and French banks ($740 billion and $640 billion respectively) (Palan, 2003). States, facilitating and organizing civil life, need to raise government revenue, but the expenses of dealing with tax avoidance are too high due to the extreme capital mobility resulting from globalisation. Hence, states are effectively unable to capture global capital, due to their territorial and economic nature being bound, and taxes are levied on personal income and consumption rather 7 than business and capital gains (Broome, 2014). In this sense, the use of coercive state power becomes obsolete, since the states are unable to change the financial capitalist social relations, but are simply reproducing and legitimising the ideas of the transnational financial hegemon. Conclusion This paper has examined whether the role of the state in the international political economy has changed following globalisation. It concludes that, after the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system (where states possessed the hegemonic capacity), the role of the state is now subordinate to a new transnational financial hegemon, and that globalisation has played a key role in establishing these new social relations, effectively making the use of coercive state power obsolete. It is argued that the ideas of the IMF and the World Bank played a key role in determining the interests of the ruling classes of states, developing a consensus across the global political economy, which has made states buy in to having subordinate positions. The ideas of the new transnational financial hegemon constrain states into playing a less significant role in determining who gets what, when and how in the global political economy. This is shown in recent developments of the 2008 financial crisis, where major bailout programmes given to the financial sector implies the reproduction of the ideas of this new hegemon, following the process of increased commodification and capital mobility. The effect of globalisation in creating an offshore world is also a clear indicator of these new social relations. Here, states are no longer able to pursue their main objective, but due to the extreme capital mobility entailed by the ideas of the financial hegemon, they are constrained to compete for attracting the dominant international capital. 8 Bibliography Broome, A., 2014. Issues and Actors in the Global Political Economy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Cox, R., 1981. Social forces, states, and world orders: beyond international relations theory. In: Approaches to World Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 85-123. Gilpin, R., 2001. Chapter 4: The Study of International Political Economy. In: Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 77-102. Overbeek, H., 2013. Transnational historical materialism: 'Neo-Gramscian' theories of class formation and world order. In: R. Palan, ed. Global Political Economy: Contemporary theories. London: Routledge, pp. 162-176. Palan, R., 2003. Chapter 1: The Offshore Economy in Its Contemporary Settings. In: The Offshore World. Ithaka: Cornell University Press, pp. 17-62. Wigan, D., 2010. Credit Risk Transfer and Crunches: Global Finance Victorious or Vanquished?. New Political Economy, 15(1), pp. 109-125. Wigan, D., 2015a. Lecture: Marxism, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School. Wigan, D., 2015b. Lecture: Money is power, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School. Wigan, D., 2015c. Global Financial Crisis, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School. Wigan, D., 2015d. Lecture: Roundup and conclusion, Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School. 9