* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Elements of Style: Literary Devices

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

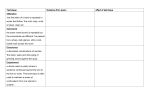

Elements of Style: Literary Devices by Mara Rockliff Poem 1 from Green Eggs and Ham This poem cannot be included in this publication because the copyright holder has denied permission and/or has electronic use conditions with which we cannot comply. Poem 2 who are you, little i who are you, little i (five or six years old) peering from some high window; at the gold of november sunset (and feeling: that if day has to become night this is a beautiful way) If somebody gave you these two poems and told you one was written by E. E. Cummings and one by Dr. Seuss, would you be able to tell which was which? If you’ve ever read anything by either writer, you almost certainly would know the first is by Dr. Seuss and the second is by E. E. Cummings. But how would you know? The answer is style—the way a writer uses language. The regular rhythm and the rhyme pattern we expect in a Dr. Seuss book, along with his silly-sounding invented words, make up his unique style. E. E. Cummings’s use of lowercase letters, words that bump into each other, and unusual punctuation make up another style. Every writer has a style, though some styles are more distinctive than others. Generations of beginning writers have tried to copy the unmistakable “plain style” of Ernest Hemingway. In fact, every year there’s an Imitation Hemingway Contest, in which writers try to create the best “really good page of really bad Hemingway.” Unexpected Connections Most writers don’t self-consciously try to come up with a style. But style comes naturally from the choices writers make when they put words on a page. A long word or a short one? A simple sentence or one that’s long and complex? A sarcastic and biting tone or one that is passionately sincere? An important part of many writers’ style is their use of figures of speech, expressions that are not literally true but that suggest similarities between usually unrelated things. Some figures of speech are so common that we use them without even noticing they're not literally true. • He was tied up in traffic. • That check you wrote bounced! • I sat at the foot of the bed. The bed doesn’t actually have a foot; we’re comparing it to a body, which has feet at the bottom. The check didn’t really bounce like a rubber ball, and the man tied up in traffic wasn’t tied with ropes—though he may have felt as if he were. Here are some of the types of figurative language you’re likely to come across: Similes compare two unlike things using a word of comparison such as like, than, as, or resembles. • Her hands were like ice. • I feel lower than a snake in a ditch. Metaphors compare two unlike things directly, without using a specific word of comparison. • His heart is made of stone. • Lewis is a rotten skunk! In an extended metaphor the comparison is extended as far as the writer wants to take it. This poem "Fame is a bee" by Emily Dickinson cannot be included in this publication because the copyright holder has denied permission and/or has electronic use conditions with which we cannot comply. Personification speaks of a nonhuman or inanimate thing as if it had human or lifelike qualities. • A falling leaf danced on the breeze. • The train eats up the miles. • The sun smiled on our cookout. Symbols, in literature, are people, places, or events that have meaning in themselves but that also stand for something beyond themselves. Moby-Dick is a white whale hunted by Captain Ahab in the novel Moby-Dick, but he is also a symbol of evil. In everyday life we have many symbols. They are called public symbols because everyone knows what they mean: A dove with an olive branch symbolizes peace; a skull and crossbones symbolizes poison; a bearded man called Uncle Sam symbolizes the U.S. government. Writers try to create fresh figures of speech to help us to see everyday things in a new way. “Her hands were as cold as ice” is a cliché—everyone’s heard it before. But what about “Her handshake would make a snowman put on gloves”? or “Her hands were colder than a lizard in an ice chest”? Unexpected Events Another way writers create a fresh and exciting style is by playing with our expectations. When reality contradicts what we expect, it’s called irony. Verbal irony occurs when we say one thing and mean something else. “That’s just great,” your friend says in a disgusted tone, and you know she means it’s not great at all. Situational irony is a situation that turns out to be just the opposite of what we’d expect. The son of the police chief is arrested for burglary. The firehouse burns to the ground. The prize encyclopedia goes to the kid who never studied for the exam. Dramatic irony occurs when we know something that a character in a book (or a movie or play) doesn’t know. “Don’t go down that dark hallway!” we want to scream, but the heroine goes anyway, and we know what she’ll find there. Putting Us There Style also comes from the way a writer uses words so that they spring to life from the page. Vivid imagery—language that creates word pictures and appeals to the senses— makes us feel that we are seeing (or hearing, touching, tasting, or smelling) what the writer is describing. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier helps us experience the start of a New England blizzard with this image: “The sun that bleak December day/Rose cheerless over hills of gray.” Writers can also appeal to the ear with dialect, a way of speaking that’s characteristic of a particular place or group of people. “Y’all come back now” tells us we’re in the South. In older movies we’d hear a New York City cabdriver say: “Dat bum wanted me to take him and huh all da way to Noo Joisey.” PRACTICE Prepare a “literary devices” wall display for your classroom. You can keep adding to this display as your experience with literary devices grows. Here is how you do it: Get seven poster boards, and give them the following labels: • Symbols • Similes • Images • Metaphors • Irony • Personification • Dialect Under each term, write its definition. Then, under each definition, write in examples that you think are interesting. You can find your examples in newspapers and magazines, as well as in the stories, poems, and novels you are reading in class and independently. Be sure to cite the author and title of the work you take each quotation from. Poetry: Sound and Sense by Mara Rockliff Words with Their Own Music Did you ever unwrap a new CD and read the song lyrics before playing the disc? Often the words by themselves don’t seem all that special. It takes music to bring them to life. Poetry is different. The words in a good poem create their own music. The English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge once defined poetry as “the best words in their best order.” Listen to how one of his own poems begins: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. —from “Kubla Khan” All Coleridge gave us were words on a page, and yet more than two centuries after he wrote them down, the music still comes through. How did he do it? Moving to the Beat If words can create the haunting music of a poem, rhythm—the repetition of stressed and unstressed syllables—provides the poem’s beat. Like many other languages, English is accented: Certain syllables get a stronger beat than other syllables. The beat of a poem comes from the patterns made by the stressed and unstressed syllables. If you say a few English words aloud, you’ll hear the beat built into them: MOUN-tain, beCAUSE, Cin-cin-NAT-i. Say your name aloud, and notice its beat. Read aloud this limerick (a limerick is a short, humorous poem with a definite pattern of rhythm). Listen to the way your voice rises and falls as you pronounce the stressed and unstressed syllables. A gentleman dining at Crewe Found quite a large mouse in his stew Said the waiter, “Don’t shout, And wave it about, Or the rest will be wanting one too!” You probably stressed the words this way ( an unstressed syllable): indicates a stressed syllable; indicates A regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is called meter. The metric pattern for lines 1, 2, and 5 of the limerick is the same: The pattern for lines 3 and 4 is slightly different. Re-read lines 3 and 4 to hear the difference. Chiming Sounds The chiming effect of rhyme adds to the music of a poem, like the tinkling of a bell or the clash of cymbals. Most rhymes in poetry are end rhymes. In the limerick the end rhymes are Crewe, stew, and too (lines 1, 2, and 5) and shout and about (lines 3 and 4). When the two rhyming lines are consecutive, they’re called a couplet. Here is a couplet with end rhymes that are spelled differently—but they rhyme: The panther is like a leopard, Except it hasn’t been peppered. —Ogden Nash, from “The Panther” Rhymes can also occur within lines; these are called internal rhymes. While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door— —Edgar Allan Poe, from “The Raven” Napping, tapping, and rapping are exact rhymes, as are leopard and peppered. Many modern poets prefer approximate rhymes (also called near rhymes, off rhymes, imperfect rhymes, or slant rhymes). Approximate rhymes use sounds that are similar but not exactly the same, like fellow and hollow or cat and catch or bat and bit. Some people think approximate rhymes sound less artificial than exact rhymes, more like real speech. Some poets use approximate rhymes because they feel that all the good exact rhymes have already been used too many times. The Beat Goes On Many poets today prefer to work in free verse. With free verse they do not have to write in meter or use a regular rhyme scheme, but that doesn’t mean that “anything goes.” Even when they write free verse, poets work to make their lines rhythmic. One way they do this is by repeating sentence patterns. You can’t miss the rhythm in these lines by Walt Whitman, one of the first American poets to use free verse: Give me the splendid silent sun with all his beams full-dazzling, Give me juicy autumnal fruit ripe and red from the orchard, Give me a field where the unmowed grass grows, Give me an arbor, give me the trellised grape… —from “Give Me the Splendid Silent Sun” Meter and rhyme aren’t the only ways in which a poet can create music with words. Note all the s sounds as you read aloud this line from “The Raven”: And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain Do you hear the rustling of that curtain in all those s sounds? This is alliteration, the repetition of consonant sounds in several words that are close together. When vowel sounds are repeated, it’s called assonance. Poe’s line also provides an example of onomatopoeia, a long word that refers to the use of words with sounds that imitate or suggest their meaning—such as rustle. Doesn’t sizzle sound like bacon frying on the grill? How about snap, crackle, pop? Words like these help poets bring sound and sense together. Some Types of Poems ballad: songlike poem that tells a story, often a sad story of betrayal, death, or loss. Ballads usually have a regular, steady rhythm, a simple rhyme pattern, and a refrain, all of which make them easy to memorize. epic: long narrative poem about the many deeds of a great hero. Epics are closely connected to a particular culture. The hero of an epic embodies the important values of the society he comes from. (Heroes of epics have—so far—been male.) narrative poem: poem that tells a story—a series of related events. lyric poem: poem that does not tell a story but expresses the personal feelings of a speaker. ode: long lyric poem, usually praising some subject, and written in dignified language. sonnet: fourteen-line lyric poem that follows strict rules of structure, meter, and rhyme. PRACTICE Find a poem you like, and prepare it for reading aloud. Here are some tips: • Be aware of punctuation, especially periods and commas. A period signals the end of a sentence—which is not always at the end of a line. You should make a full stop when you come to a period. • If a line of poetry doesn’t end with punctuation, don’t stop. Continue reading until you reach a punctuation mark. • If the poem is written in meter, don’t read it in a singsong way. Read the poem for its meaning, using a natural voice. Let the music come through on its own.