* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PERICARDIAL DISEASES

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

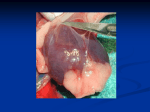

PERICARDIAL DISEASES PROF.DR. FERDA ÖZKAN To learn the structure of pericardium To learn the types of pericardial effusions To learn the types of pericarditis The pericardium is comprised of the parietal pericardium (an outer fibrous layer) and the visceral pericardium (an inner serous membrane made of a single layer of mesothelial cells). The visceral pericardium is attached to the epicardial fat and reflects back on itself to form the parietal pericardium. Pericardial physiology includes 3 main functions. • First, mechanical function, the pericardium promotes cardiac efficiency by limiting acute dilation, maintaining ventricular compliance with preservation of the Starling curve, and distributing hydrostatic forces. It also creates a closed chamber with subatmospheric pressure that aids atrial filling and lowers transmural cardiac pressures. •Second, membranous function: -shields the heart by reducing external friction and acting as a barrier against extension of infection and malignancy. •Third, ligamentous function: -the pericardium fixes the heart anatomically. Pericardial lesions Pericardial lesions are almost always associated with disease in other portions of the heart or surrounding structures or secondary to a systemic disorder; isolated pericardial disease is unusual. Despite the large number of etiologies of pericardial disease, there are relatively few anatomic forms of pericardial involvement. Pericardial Effusion Normally there is about 30 to 50 ml of thin, clear, straw-colored, translucent fluid in the pericardial space. Under a variety of circumstances, pericardial effusions may appear An effusion accumulates slowly and is rarely larger than 500 ml Rarely a large volume or rapid accumulation of a lesser volume may embarrass diastolic filling of the heart. Serous effusion (in cardiac failure) the fluid is completely clear, or straw colored, and sterile; the serosal surfaces remain smooth. Serosanguineous (in blunt chest trauma) Chylous effusions (in lymphatic obstruction) • contain lipid droplets • benign or malignant mediastinal neoplasms. The pericardium normally contains as much as 50 mL of an ultrafiltrate of plasma. Drainage occurs via the thoracic duct and the right lymphatic duct into the right pleural space. Hemopericardium Hemopericardium is the accumulation of pure blood in the pericardial sac (distinct from hemorrhagic pericarditis, a condition in which there is an inflammatory exudate containing blood mixed with pus). Hemopericardium is almost invariably due to rupture of the heart wall secondary to • myocardial infarction, • traumatic perforation, or rupture of the intrapericardial aorta. Blood rapidly fills the sac under greatly increased pressure Producing cardiac tamponade Small amounts of blood may result from the trauma sustained during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pericarditis Inflammations of the pericardium are usually secondary to a variety of • cardiac diseases, • to systemic disorders, or • to metastases from neoplasms arising in remote sites. Primary pericarditis is unusual and almost always of viral origin. The various etiologies usually evoke an acute pericarditis, Tuberculosis and fungi produce chronic reactions. Acute Pericarditis Acute pericarditis is an inflammation of the pericardium characterized by chest pain, pericardial friction rub, and serial electrocardiographic changes. Classification (Pathology): • • • • • Serous Pericarditis Fibrinous and Serofibrinous Pericarditis Purulent or Suppurative Pericarditis Hemorrhagic Pericarditis Granulomatous Pericarditis. Etiology Bacterial • 1-8% of cases and causes purulent pericarditis. • Direct extension: pulmonary extension, myocardial abscess/endocarditis, penetrating injury to chest wall from either trauma or surgery, subdiaphragmatic suppurative lesion. • Hematogenous spread : bacteriemia, sepsis, pyemia • Organisms: Gram-positive species such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and other Streptococcus species, Staphylococcus, and gram-negative species, including Proteus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Shigella, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae. Less common organisms include Legionella, Nocardia, and Actinobacillus, Rickettsia and Lyme borreliosis (Borrelia burgdorferi). Anaerobes also have been isolated in 40% of patients in reviews of the pediatric population. Tuberculosis This accounts for 4% of cases. Especially in high-risk groups such as elderly patients in nursing homes. Elevated adenosine deaminase in pericardial fluid is useful for diagnosing tuberculosis. High adenosine deaminase values may indicate a poorer prognosis. Approximately half the patients develop constrictive pericarditis. Viral • 1-10% of cases. • Causative viruses include coxsackievirus B, echovirus, adenoviruses, influenza A and B viruses, Enterovirus, mumps virus, EpsteinBarr virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus type 1, varicella zoster virus, measles virus, parainfluenza 2 virus, and respiratory syncytial virus. • Viruses, especially coxsackie B and influenza, can occur as seasonal epidemics. • It usually is a short self-limited disease lasting 1-3 weeks. • Patients may have associated myocarditis. • HIV: Pericardial involvement is frequent, but it usually is an asymptomatic pericardial effusion of small volume. It is found more frequently in advanced HIV infection, with one study noting right atrial diastolic compression in 5% of cases. Symptomatic pericarditis is observed in less than 1%. Etiology can include usual causes, opportunistic infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and HIV virus. Other infectious agents include the following: • Fungal organisms include Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, and Candida. • Parasitic organisms include Entamoeba, Echinococcus, and Toxoplasma. Idiopathic • Between 26% and 86% of cases are idiopathic in nature. • No clinical features distinguish these from viral pericarditis. • Most likely, the majority of idiopathic cases are undiagnosed viral infections. • Seasonal peaks occur in spring and fall. Rheumatoid arthritis • Autopsy studies show incidence of 11-50% in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). • Pericardial involvement usually is clinically silent. • Diagnosis is suggested by serous or hemorrhagic -pericardial fluid with a glucose level of less than 45 mg/dL, -white blood cell count higher than 15,000/mm2 with -cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, -protein level higher than 5 g/dL, -low total serum hemolytic complement (CH50), -high immunoglobulin G (IgG) level, and -high rheumatoid factor. -Cholesterol levels may be high in the fluid of patients with RA who have nodules. Systemic lupus erythematosus • 25% of patients with lupus. • Autopsy series reveal pericardial involvement in 62%. • Fluid analysis reveals -increased leukocytes of (PMN) - high protein, - low-to-normal glucose, - low complement, and possibly a - pH of less than 7. - Also, it will have positive autoantibodies, such as the antinuclear antibody or anti–doublestranded DNA.. • Development of tamponade and constrictive pericarditis is rare. Scleroderma • 5-10% of patients with scleroderma. • Autopsy incidence rate is 70%. • Pericardial effusions are observed in 40% of patients and can be due to scleroderma, myocardial failure (restrictive cardiomyopathy), and renal failure. • Restrictive cardiomyopathy and pericardial constriction can coexist. • Usually, pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, and systolic dysfunction are observed. • These patients have a poor prognosis. Rheumatic fever • It often accompanies endocarditis and myocarditis, with a worse prognosis. • In adults, pericarditis may not occur with myocardial or valvular involvement, and it is associated with a better prognosis. • Antistreptolysin O titer usually is greater than 400. • Rarely is a large effusion present. Sarcoidosis •Pericarditis is present in autopsies of approximately 25% of these patients. •Patients may not have significant myocardial infiltration. •It rarely causes cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis. Pericarditis is described in other inflammatory conditions, including the following: • Sjögren syndrome • Mixed connective tissue disease • Reiter syndrome • Ankylosing spondylitis • Inflammatory bowel disease • Wegener granulomatosis • Vasculitis, such as giant cell arteritis and polyarteritis • Polymyositis • Behçet syndrome • Whipple disease • Familial Mediterranean fever • Serum sickness Renal failure • Renal failure accounts for approximately 12% of cases. • In the predialysis era, pericarditis developed in 35-50% of patients with uremia who had chronic renal failure and less commonly in those with acute renal failure. • Death often followed in several weeks. • With dialysis, the incidence rate is less than 10%. Pericarditis occurs after the onset of dialysis in 812%. Some authors suggest that uremic pericarditis is a different entity from dialysis-associated pericarditis. Asymptomatic pericardial effusions can occur in 3662% of patients with uremia who require dialysis. The presence of a large pericardial effusion that persists for longer than 10 days after intensive dialysis has a high likelihood of causing tamponade. Treatment is intensive dialysis. Hypothyroidism • 4% of cases. • Pericardial involvement usually is observed with severe hypothyroidism. • Patients may develop large pericardial effusions, but rarely do they develop tamponade. • Pericardial fluid often is clear with high protein and cholesterol levels and few cells. • Myocardial involvement is common. Cholesterol pericarditis •This also is called gold-paint pericarditis. •Granulomatous pericarditis has been implicated in some cases. •Development of constriction is rare. Myocardial infarction • After a transmural infarction, a fibrinous pericardial exudate appears within 24 hours. It begins to organize at 4-8 days, and it completes organization at 4 weeks. • Prior to thrombolytic therapy, infarct-associated pericarditis ranges from 7-23%. At autopsy, almost all patients were noted to have localized fibrinous pericarditis overlying the area of infarction. • With thrombolytic therapy and direct infarct angioplasty, the incidence of infarct-associated pericarditis has decreased to 5-8%. • Overall, pericardial involvement indicates larger infarction, greater incidence of left ventricular dysfunction, and greater mortality. • Pericarditis usually heals without consequence. • Effusions may occur, but they rarely lead to tamponade. Dressler syndrome • Pericarditis associated with Dressler syndrome usually is observed 2-3 weeks after a myocardial infarction. • It may be a unique autoimmune-mediated phenomenon to myocardial antigens, or it may merely be an unrecognized postmyocardial infarction pericarditis. • Patients may develop pulmonary infiltrates and large pericardial effusions. • Because of the risk of hemorrhagic pericarditis, anticoagulant therapy should be stopped. Postpericardiotomy syndrome • This is similar to Dressler syndrome, except it occurs after cardiac surgery. • Several series note an incidence rate of 1040%. • Approximately 1% develop tamponade. • Pericardial effusions can occur in the absence of typical features of postpericardiotomy syndrome. • The effusions were more common after heavy postoperative bleeding. • Pericarditis is observed with other cardiac instrumentation, including percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and pacemaker implantation. Usually, it is associated with epicardial/pericardial Neoplasm • 5-17 % of cases. • Neoplastic disease, particularly advanced, is the most frequent cause of tamponade in the hospital. • Occasionally, the tumor encases the heart and causes constrictive pericarditis rather than tamponade. • Primary neoplasm of the heart and pericardium are rare. Pericardial mesothelioma and angiosarcoma are lethal malignancies with aggressive local spread that respond poorly to treatment. Infants and children can present with a teratoma in the pericardial space. These often can be removed successfully. • Most cases occur as a result of metastatic disease. Autopsy studies have noted that approximately 10% of patient with cancer, develop cardiac involvement, and often, it is clinically silent. The neoplastic cells reach the pericardium through the bloodstream via lymphatic system, or local growth. • Metastatic tumors: Lung cancer, including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, and small cell, accounts for approximately 33% of cases. Breast cancer accounts for 25%. Leukemia and lymphoma, including Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin, account for 15% of cases. Malignant melanoma represents another 5%. Kaposi sarcoma with the AIDS. • The pericardial carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level often is elevated. •Cytology is positive in 80-90% of breast and lung cancer cases, but the percentage is lower in other malignancies. Obstruction of the lymphatic drainage can cause the pericardial effusion to be more significant than the tumor mass. Irradiation •Pericardial disease is the most common cardiac toxicity. •High incidence is observed with high doses, especially greater than 4000 rad. •It can present as acute pericarditis, with or without effusion; chronic constrictive pericarditis; or effusiveconstrictive pericarditis. Drugs • Some medications, including penicillin and cromolyn sodium, induce pericarditis through a hypersensitivity reaction. • The anthracycline antineoplastic agents, such as doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, have direct cardiac toxicity and can cause acute pericarditis and myocarditis. • Pericarditis can develop from a drug-induced SLE syndrome from medications, including procainamide, hydralazine, methyldopa, isoniazid, mesalazine, and reserpine. • Methysergide causes constrictive pericarditis through mediastinal fibrosis. • Dantrolene, phenytoin, and minoxidil produce pericarditis through an unknown mechanism. Serous Pericarditis Serous inflammatory exudates are characteristically produced by noninfectious inflammations, such as RF systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, tumors, and uremia., In some instances, a well-defined viral infection elsewhere –upper respiratory tract, pneumonia, parotitis– antedates the pericarditis and serves as the primary focus of infection. Serous Pericarditis This diagram depicts the appearance of a serous pericarditis. The amount of inflammation is minimal, so no exudation of fibrin occurs. The dark stippled dots in the yellow fluid and on the epicardial surface represent scattered inflammatory cells. Serous pericarditis is marked by fluid collection. Rarely, the fluid collection may be large enough to cause tamponade. Fibrinous and Serofibrinous Pericarditis Most frequent type of pericarditis a more or less serous fluid mixed with a fibrinous exudate. Common causes include • • • • • • • • • acute myocardial infarction, the postinfarction (Dressler’s) syndrome uremia, chest radiation, RF, systemic lupus erythematosus, trauma cardiac surgery pneumonia. Fibrinous Pericarditis This diagram depicts the appearance of a fibrinous pericarditis. The red-pink squiggly lines extending from the epicardial surface into the yellow fluid represent the strands of fibrin. This type of pericarditis is typical of uremia with renal failure, underlying myocardial infarction, and acute rheumatic carditis Fibrinous Pericarditis A window of adherent pericardium has been opened to reveal the surface of the heart. There are thin strands of fibrinous exudate that extend from the epicardial surface to the pericarial sac. This is typical for a fibrinous pericarditis Fibrinous Pericarditis This is an example of a fibrinous pericarditis. The surface appears roughened from the normal glistening appearance by the strands of pink-tan fibrin. Fibrinous Pericarditis The epicardial surface of the heart shows a shaggy fibrinous exudate. This is another example of fibrinous pericarditis. This appearance has often been called a "bread and butter" pericarditis, but you would have to drop your buttered bread on the carpet to really get this effect. The fibrin often results in the the finding on physical examination of a "friction rub" as the strands of fibrin on epicardium and pericardium rub against each other. The pericardial surface here shows strands of pink fibrin extending outward. There is underlying inflammation. Eventually, the fibrin can be organized and cleared, though sometimes adhesions may remain. Purulent or Suppurative Pericarditis The invasion of the pericardial space by infective organisms. The routes of organisms: • (1) direct extension from neighboring inflammations, such as an empyema of the pleural cavity, lobar pneumonia, mediastinal infections, or extension of a ring abscess through the myocardium or aortic root in infective endocarditis • (2) seeding from the blood; • (3) lymphatic extension; • (4) direct introduction during cardiotomy. Immunosuppressive therapy potentiates all of these pathways. The exudate ranges from a thin to a creamy pus of up to 400 to 500 ml in volume. The serosal surfaces are reddened, granular, and coated with the exudate. Microscopically there is an acute inflammatory reaction. Sometimes the inflammatory process extends into surrounding structures to induce a so-called mediastinopericarditis. Acute purulent pericarditis An exudate is an inflammatory extravascular fluid that has a specific gravity greater than 1.020 and contains a large amount of protein and cellular debris. This is an example of an exudate that is seen with pericarditis and is often called bread and butter pericarditis due to its appearance. Purulent is synonymous with suppurative and implies a non-viral etiology. This is a purulent pericarditis. Note the yellowish exudate that has pooled in the lower pericardial sac seen been opened here. Etiology: • A preexisting or concurrent infection such as pneumonia with or without empyema, meningitis, osteomyelitis, arthritis, or other soft tissue infections. • Patients recovering from thoracic, cardiac, or esophageal surgery are at risk for purulent pericarditis. • Purulent pericarditis has been reported in patients recovering from traumatic injury. • The organisms that most commonly cause purulent pericarditis are Staphylococcus aureus, H influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Less common organisms include gramnegative enteric bacilli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella species, Francisella tularensis, and anaerobic bacteria and fungi (Histoplasma species, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, Aspergillus species, Candida species). S. aureus • This is the most common organism in children, causing approximately 40% of cases. • Pericarditis occurs concomitantly with pneumonia with empyema and less often with acute osteomyelitis or soft tissue abscess. • Rarely, pericarditis is associated with S aureus endocarditis. • Necrotizing infection and exotoxin production lead to increased incidence of shock and higher mortality risk. • Within the first 3 months after cardiac surgery, S aureus is the most common H. İnfluenzae • This is the second most common organism listed in most reported pediatric case series of purulent pericarditis, • Infection of the upper or lower respiratory tract frequently precedes pericarditis caused by H influenzae. • Purulent pericarditis may occur with H influenzae meningitis. • H influenzae produces very thick fibrinopurulent exudate. N. meningitidis • Pericarditis occurs in approximately 5% of young adults with meningococcemia. • The clinical course is often milder than with other causes of purulent pericarditis. • Pericardial effusion can be detected at the onset of the illness or later in the course of the infection. S. pneumoniae: • At one time, S pneumoniae was the leading cause of purulent pericarditis, but it has become much less common perhaps because of widespread use of antibiotics. Other organisms • Gram-negative enteric bacilli and anaerobes or fungi, are rare but should be considered in patients who are immunocompromised. • Aspergillus pericarditis arises as a result of pulmonary infection in patients who are immunocompromised. • Mycoplasma pneumoniae pericarditis is associated with pulmonary disease. Complications: • Myocardial involvement • Heart failure • Constrictive pericarditis Constrictive pericarditis is a rare complication. increased systemic venous pressure, hepatomegaly, dyspnea, and decreased urine output. Hemorrhagic Pericarditis An exudate composed of blood mixed with a fibrinous or suppurative effusion is most commonly caused by tuberculosis direct malignant neoplastic involvement cardiac surgery. The surface of the heart with hemorrhagic pericarditis demonstrates a roughened and red appearance. Hemorrhagic pericarditis is most likely to occur with metastatic tumor and with tuberculosis (TB). TB can also lead to a granulomatous pericarditis that may calcify and produce a "constrictive" pericarditis. Granulomatous Pericarditis Tuberculosis, fungal infections, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis. Caseation within the pericardial sac is tuberculous in origin • Infrequently mycotic infections evoke a similar pattern. • The pericardium is usually involved by direct spread from tuberculous foci within the tracheobronchial nodes. • Caseous pericarditis is the most frequent antecedent of disabling, fibrocalcific, chronic constrictive pericarditis. Chronic or Healed Pericarditis Organization merely produces • plaque-like fibrous thickenings • thin, delicate adhesions (rarely cause impairment of cardiac function) • complete obliteration of the pericardial sac. This fibrosis yields a delicate, stringy type of adhesion between parietal and visceral pericardium called adhesive pericarditis, which rarely hampers or restricts cardiac action. In some cases, however, healed pericarditis can be clinically important, especially when it takes the form of adhesive mediastinopericarditis or constrictive pericarditis. Adhesive Mediastinopericarditis May follow: • a suppurative or caseous pericarditis, • previous cardiac surgery, • irradiation to the mediastinum. The pericardial sac is obliterated, and adherence of the external aspect of the parietal layer to surrounding structures produces a great strain on cardiac function. The increased workload causes cardiac hypertrophy and dilatation, which Constrictive Pericarditis The heart may be encased in a dense, fibrous, or fibrocalcific scar that limits diastolic expansion and seriously restricts cardiac output. History of a previous suppurative, hemorrhagic, or caseous (tuberculous) pericarditis, but more often the cause is uncertain. The pericardial space is obliterated, and the heart is surrounded by a dense, adherent layer of scar or calcification, often 0.5 to 1.0 cm thick, that can resemble a plaster mold in extreme cases (concretio cordis). Cardiac hypertrophy and dilatation cannot occur because of the dense enclosing scar, Etiology: • Chronic constrictive pericarditis develops insidiously; frequently, an etiology is never determined. • In some (approximately 10%) patients, an antecedent acute pericarditis exists. Tuberculosis is the most frequent known cause of chronic constrictive pericarditis. Other causal organisms include (among others) staphylococci, streptococci, and fungi such as histoplasmosis. Rheumatoid disease Sarcoidosis Mediastinal radiation Trauma (hemopericardium) Status post–cardiac surgery (postpericardiotomy syndrome) Uremia Neoplastic disease Postinfectious (bacterial) pericarditis Various metabolic and genetic disorders. Pericardium in Rheumatoid arthritis The heart is involved in 20 to 40% of cases of severe prolonged rheumatoid arthritis. Fibrinous pericarditis (dense fibrous adhesions) In the early stages of this process, rheumatoid inflammatory granulomatous nodules resembling those that occur subcutaneously may be identifiable deep to the pericardial surfaces (rheumatoid nodules may involve the myocardium, endocardium, valves of the heart, and root of the aorta). Amyloid involving the heart can also occur secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Thank you