* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download View the pdf here

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems wikipedia , lookup

Geocentric model wikipedia , lookup

Modified Newtonian dynamics wikipedia , lookup

Astrobiology wikipedia , lookup

Anthropic principle wikipedia , lookup

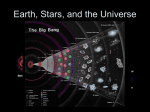

Shape of the universe wikipedia , lookup

Extraterrestrial life wikipedia , lookup

Non-standard cosmology wikipedia , lookup

Outer space wikipedia , lookup

Observable universe wikipedia , lookup

Expansion of the universe wikipedia , lookup

Lambda-CDM model wikipedia , lookup

Physical cosmology wikipedia , lookup

Future of an expanding universe wikipedia , lookup

Flatness problem wikipedia , lookup