* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

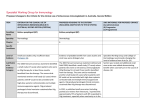

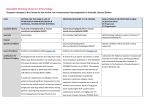

Download NBA - The Criteria for the clinical use of intravenous immunoglobulin

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript