* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download THEORY BUILDING AND DEMOCRACY: AN APPRAISAL AND

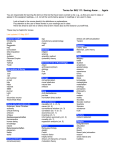

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript