* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download sinus node dysfunction - Continuing Medical Education

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

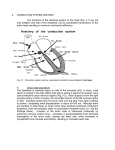

E C G E D U C AT I O N SINUS NODE DYSFUNCTION Part two of an educational series on ECG analysis and arrhythmia diagnosis Dr Ronal M Jardine — Cardiologist Linmed Hospital First described in 1909 by Laslett, sinus node dysfunction (SND) has increasingly been shown over the last century to be responsible for symptoms, typically syncope or pre-syncope, but also less specific complaints such as fatigue, dyspnoea, angina, a change in mental state (particularly in the elderly) or palpitations if atrial tachy-arrhythmias occur. The overall incidence is estimated to be 0.17% and it is clearly a phenomenon of advancing age. ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC MANIFESTATION OF SINUS NODE DYSFUNCTION • Inappropriate sinus bradycardia. Sinus bradycardia is defined as a sinus rate of less that 50 bpm, and is sometimes appropriate, e.g. due to athletic vagotonia in young individuals and during sleep. It is inappropriate if it is persistent, or responsible for symptoms, or accompanied by chronotropic incompetence (vide infra). • Sinus arrest (or sinus pause). Pauses in sinus rhythm of up to 3 seconds are seen in 11% of normal patients during holter monitoring, and even more commonly in athletes (36%). In contrast pauses of > 3 seconds are rare in normal individuals and are generally regarded as pathological. They represent a failure of impulse generation within the SA node, and as opposed to sino-atrial exit block, the sinus pause when measured is not a multiple of the preceding sinus cycle length. • Sino-atrial exit block. In contrast, in SA exit block, the impulse is generated within the SA node but fails to enter the surrounding atrial tissue. As with AV block, there are 3 degrees of block, but only 2° SA exit block can be diagnosed on the ECG with certainty, when a pause is noted which is a multiple of the preceding sinus cycle length, e.g. 2 X, 3 X, or 4 X as long. 1 degree SA block is not evident on the surface ECG, and 3 degree SA exit block will produce prolonged pauses not distinguishable from sinus arrest. The distinction is not however important as in both cases if there are symptoms, treatment is necessary. • Tachy-brady syndrome. Typically this includes a propensity for tachycardia, usually atrial fibrillation, but sometimes atrial flutter or other atrial tachycardia, and bradycardia, usually sinus bradycardia or sinus pauses. The ECG attached demonstrates atrial fibrillation followed by a pause before the resumption of normal sinus rhythm 208 CME April 2004 Vol.22 No.4 Fig.1 and classically this would produce a complaint of a paroxysm of palpitations followed by syncope/pre-syncope. • Post-cardioversion asystole. If external electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation is followed by a prolonged pause before the re-initiation of sinus rhythm, sinus node dysfunction is present. • Chronotropic incompetence. Failure of acceleration of the sinus node in response to exercise or infusion of a beta 1-stimulant is abnormal and termed ‘chronotropic incompetence’. In contrast, young athletes with vagotonic sinus bradycardia have normal acceleration, albeit with rapid deceleration in the recovery phase after exercise. CAUSES OF SINUS NODE DYSFUNCTION A number of pathological mechanisms cause the aforementioned abnormalities. Failure of impulse generation and failure of the impulse to exit the SA node have been mentioned, but there is also failure of physiological subsidiary pacemaker activity (failed escape rhythm), and also increased atrial vulnerability to fibrillation and other tachyarrhythmias. The causes of sinus node dysfunction are listed in Table I. Intrinsic causes imply organic disease of the SA node, whereas extrinsic causes are the effects of drugs, autonomic nervous system and other physiological changes on the node. INVESTIGATIONS FOR SINUS NODE DYSFUNCTION • ECG. Clearly a recording of a full 12-lead ECG during symptoms is diagnostic, but often logistically difficult. For that reason, a number of techniques for prolonged ECG monitoring are necessary. Ambulatory 24-hour ECG recording (Holter) is very useful, but has a relatively low yield and may have to be repeated a number of times before diagnostic abnormalities are recorded. Alternatively, patients can be given an event-triggered ECG E C G E D U C AT I O N T ABLE I. C AUSES OF SINUS NODE DYSFUNCTION INTRINSIC CAUSES • Idiopathic degenerative disease • Coronary artery disease • Cardiomyopathy • Hypertension • Infiltration (amyloid, haemochromatosis, tumours) • Collagen disease (scleroderma and SLE) • Surgical trauma (NB cardiac transplantation) • Congenital:familial congenital heart disease surgery for congenital heart disease especially the Mustard operation for transposition and ASD closure especially sinus venosus type • Musculo-skeletal disorders (myotonic dystrophy, Friedreich’s ataxia) EXTRINSIC CAUSES • Drugs: beta-blockers calcium channel blockers digoxin adenosine sympatholytic anti-hypertensives (clonidine, methyldopa and reserpine) anti-arrhythmic drugs: type IA type IC type III others: lithium cimetidine amitriptyline phenytoin phenothiazine • Autonomic effects: athletic vagotonia neuro-cardiogenic syncope other neurally-mediated syncopes e.g. carotid sinus hypersensitivity • Other: electrolyte abnormalities: hyperkalaemia, hypercarbia hypothyroidism raised intracranial pressure hypothermia sepsis recorder to self-record at the time of any symptoms, and then transmit this ECG by telephone line to a central monitoring service. Typically patients would keep this recorder for 2 - 4 weeks. The frequency of symptoms guides the choice of which of these 2 forms of monitoring to use in the first instance. • Exercise ECG testing is helpful in the diagnosis only in terms of establishing that there is chronotropic incompetence, i.e. that this is not athletic vagotonia, and this will also guide in the choice of pacemaker, i.e. some form of rate-responsive pacemaker will be necessary for chronotropic incompetence. • Autonomic testing. Two groups of autonomic test can yield some information, specifically as to whether this is an intrinsic or extrinsic form of sinus node dysfunction. Testing of autonomic reflexes with e.g. carotid sinus massage, the Valsalva manoeuvre, and tilt testing is possible. Of these, only carotid sinus massage is mandatory is all cases, because the presence of carotid sinus hypersensitivity indicates the need for a dual-chambered pacemaker as opposed to a single-chambered atrial pacemaker which is applicable to most forms of sinus node dysfunction. Pharmacological tests of autonomic function by injections of isoprenaline, atropine, propranolol, or the combination of atropine and propranolol have been studied. The atropine plus propranolol combination effectively results in total autonomic blockade, and allows the measurement of a parameter called the ‘Intrinsic Heart Rate’ for which there are defined normal values, and if lower than this, supports the diagnosis of sinus node dysfunction if it is in question. • Electro-physiological testing. Measurement of the intrinsic heart rate can be done at the time of electrophysiological testing also. A number of electrophysiological April 2004 Vol.22 No.4 CME 209 E C G E D U C AT I O N parameters have been devised over the past 30 years to enable a diagnosis of sinus node dysfunction, but they all suffer from a relatively low sensitivity of 70%, albeit with an acceptable level of specificity of about 90% overall. These tests are also tedious and suffer from a wide range of reported normal values. Consequently they are not widely applied at present. They include sinus node recovery time (SNRT) after a period of atrial pacing, to test overdrive suppression of sinus node automaticity, and the corrected SNRT (CSNRT) taking into account the underlying sinus rate. Sino-atrial conduction time (SACT) through timed extra-stimuli during sinus rhythm or an atrial paced rhythm, measures conduction in and out of the node. At the same time, sinus node effective refractory period (SNERP) is measurable. thrombo-embolism, certainly in patients aged 65 years or more, with the target INR of 2.0 - 3.0. Drug therapy for the brady-arrhythmias of sinus node dysfunction is generally not recommended (vagolytic and sympathomimetic drugs and hydrallazine have not been found to be useful in the past). There is a small group of young patients with sinus node dysfunction, which is probably vagotonic, who respond to long-acting theophylline as symptomatic treatment until the sinus node dysfunction has self-resolved. This small niche for drug therapy does obviate the need for permanent pacemaker implantation in young persons, which is highly desirable. ß The I NECG A isNthe U Tmost S Huseful E L L non-invasive test in medicine Treatment •Asymptomatic patients. It is clear from natural history studies that the long-term prognosis for patients with sinus node dysfunction is no different from the general population provided that there is no associated structural heart disease and that atrial fibrillation is not part of the presentation. This means there is no mortality benefit from permanent pacemaker implantation in this group. They must merely avoid the drugs known to suppress the SA node (see Table I), and if atrial fibrillation is known to be present, must receive chronic anti-coagulation with warfarin to keep the INR between 2.0 and 3.0. •Symptomatic patients. Permanent pacemaker implantation is a very effective form of symptom relief. It abolishes brady-arrhythmic symptoms, and if an appropriate A-V sequential mode is used, also diminishes the frequency of atrial fibrillation. Numerous studies have shown the detrimental effects of single chambered ventricular pacing (VVI/VVI-R) in patients with sinus node dysfunction, because of the increased incidence of atrial fibrillation due to intact retrograde VA conduction. This has swayed most cardiologists towards implantation of a dual-chambered pacing system (DD/DDDR), and this has been driven on by unfounded fears about the possibility of future AV block in these patients. If at the time of presentation/implantation there is no evidence of AV conduction delay (e.g. prolongation of the PR interval, bundle branch block, an AV Wenckebach rate of <120 bpm, prolongation of the HV interval at EP study, or documented 2° or 3° AV block), the subsequent risk of AV block is 2.7% per annum and this figure includes 1° and Wenckebach type 2° AV clock. Therefore, a simpler, cheaper, and equally effective form of pacing is singlechambered atrial pacing (AAI/AAI-R). In cases of the tachy-brady syndrome, atrial pacing alone will diminish the risk for atrial tachy-arrhythmias, but if they recur, anti-arrhythmic drugs can be used, bearing in mind their possibility for influencing AV nodal conduction. Anticoagulation with warfarin is mandatory for prevention of 210 CME April 2004 Vol.22 No.4 • Asymptomatic sinus pauses > 2 seconds occur in 11% of normal individuals and even more commonly in athletes (36%). • Tests for sinus node dysfunction at electro-physiological study are only 70% sensitive and 90% specific. • The key to successful treatment of sinus node dysfunction is to establish a link between ECG abnormalities and symptoms – a difficult task. • Single-chamber ventricular pacing is a poor form of treatment for sinus node dysfunction because it promotes the development of atrial fibrillation. • Provided that there is no evidence of AV conduction delay at the time of implantation/presentation, singlechamber atrial pacing is a good treatment for sinus node dysfunction because the subsequent development of AV block is only 2.7% per annum. A SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP OF SA HEART ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 2826, Benoni, 1500 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 021-448 7062 This article is sponsored by Johnson & Johnson Medical, in the interest of continued medical education For more information and referrals, please send your request to [email protected]