* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Redwood Forest - Fort Hays State University

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

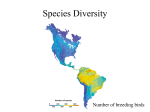

Coastal Forests Redwood National and State Parks California Department of Biological Sciences, Fort Hays State University Instructor: Mark Eberle Course Homepage Our last stop along the Pacific Coast is the redwood forest in northern California. Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) is confined to a section of the lowland coastal forest in northern California and a small area of adjacent southern Oregon. The redwood forest is the southern end of the temperate coastal rain forest that extends northward into Alaska. Northern California receives less total precipitation than the Washington and Oregon coasts to the north, but it compensates for that deficiency with regular summer fogs, which are an important component to the regional hydrologic cycle. About 34% of the annual water input in redwood forests of northern California comes from fog drip from the trees, compared to only about 17% in areas where trees are absent (Dawson, 1998). Thus, Coast Redwoods are important in making this water available within the ecosystem, not just for themselves, but also for other plants. During the foggy summers, about 19% of the water in Coast Redwoods and about 66% of the water in understory plants is derived from fog drip onto the soil. Morning Fog at Gold Bluffs Beach, Prairie Creek Redwood SP, California Photograph by Curtis Wolf, July 2005 The redwood forest also includes Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis) and other species that we saw at sites visited prior to this on the coasts of Oregon and Washington. However, in the often foggy river valleys, Coast Redwoods dominate the forest community, with a lush understory of Sword Ferns (Polystichum munitum) and Redwood Sorrel (Oxalis oregana) (also known as Oregon Oxalis; surrounding the frog in the photograph on the right at the bottom of the last page). A spectacular display of ferns covers the walls of Fern Canyon, which opens toward the Pacific Ocean. Natural meadows, such as the one at the entrance to our campground at Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, offer excellent opportunities to see Elk (Cervus canadensis), especially in the morning or evening. Fern Canyon, Prairie Creek Redwood SP, California (with Mark Eberle and Aaron Austin) Photograph by Curtis Wolf, July 2005 Coast Redwoods are adapted to floods and fires. One adaptation is the presence of dormant buds near the base of the tree. If a flood deposits silt around the base of its trunk, a redwood will grow new roots from these buds to keep its roots close to the surface. In addition, redwoods that are burned or cut can sprout new stems from these buds, forming a “fairy ring” of new trunks (next page, right photograph). Masses of these buds sometimes bulge from the side of the tree to form a burl. The thick bark and virtually nonflammable pitch also help Coast Redwoods resist fire damage. However, some fires are severe enough to kill trees, and large floods can topple redwoods growing in river valleys, but the bare seedbed cleared by the fire or deposited by the flood is ideal for the establishment of Coast Redwood seedlings (information from summary by Johnston, 1994:15‒19). Forest Trail and Redwood “Fairy Ring”, Redwood NP/SP, California Photographs by Alaina Elliott, August 1997, and Mark Eberle, July 2002 One important aspect of forest ecology we are unable to explore occurs in the canopies of tall trees of old-growth forests. The summary presented here is derived from studies of this ecosystem by Stephen Sillett and others, and he provides some excellent images and descriptions of the canopy ecosystem on his website (accessed 24 November 2009). Just as we have seen new trunks established as fairy rings near the ground, damage in the trunks near the tops of trees can result in the growth of “reiterated trunks,” which can also be damaged and give rise to their own reiterated trunks. Damaged branches also can give rise to reiterated trunks, after which they are referred to as “limbs” that develop buttresses on their lower surface to help support their weight. The result of this potential regrowth is that the number of reiterated trunks on a single tree can be in the hundreds, providing incredible structural diversity in the canopies. The crotches of reiterated trunks and the large platforms on the surface of limbs provide habitat for lichens and epiphytic vascular plants, such as ferns, shrubs, and even trees. This increase the structural diversity of the Coast Redwood canopy provides habitat for a variety of animals, including the Wandering Salamander (Aneides vagrans). About 10‒20% of Coast Redwood leaves are shed annually, and some collect in the crotches or on limbs, where they decompose and contribute to the initial canopy soil. Canopy soils in the redwood canopy are most frequently associated with Leather-leaf Fern (Polypodium scouleri), which can form deep mats composed primarily of dead fern rhizomes. One fern mat had an estimated 336 kg (740 pounds) of dry mass, and held 500 L of water (dry summer season) to 1,500 L (wet winter season). Fern mats formed in the crotch of reiterated trunks typically hold more moisture than those on limbs. Red-legged Frogs, Del Norte Coast Redwoods SP and Prairie Creek Redwoods SP, California Photographs by Jenn Nylund, August 1997, and William Cook, August 2000 Literature Cited Dawson, T. E. 1998. Fog in the California redwood forest: ecosystem inputs and use by plants. Oecologia 11:476‒485. Johnston, V. R. 1994. California Forests and Woodlands: A Natural History. University of California Press, Berkeley. Next Stop: Sierra Nevada Forests | Species Checklists | Return to Trip Summary Homepage